4 December 2025 by Shahriar Lahouti.

CONTENTS

- Preface

- Hemostasis Balance

- Bleeding Patients

- Patient with Thrombosis

- When to start anticoagulation in the ED: Initiation

- Universal ED Anticoagulation Initiation Pathway

- Right Risk-Assessment

- Patient disposition pathway

- Ensuring Safe Follow-Through

- Clinical & Laboratory Monitoring

- 📊Table: Monitoring anticoagulants

- Critical Heparin-Specific Monitoring Alerts

- Systems Support & Care Coordination

- Clinical & Laboratory Monitoring

- Specific population

- Summary & implementory guide

- Appendix

- References

Preface

The emergency department is ground zero for the complications and critical decisions surrounding anticoagulant therapy. From the patient with a life-threatening bleed on an unfamiliar direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) to the newly diagnosed pulmonary embolism who may be safe for discharge, these drugs demand swift, confident management. This guide cuts through the complexity to provide the emergency physician with a pragmatic, actionable framework. We will focus on the core tasks: rapidly identifying the agent, managing major hemorrhage with specific reversal strategies, safely initiating therapy when indicated, and making sound disposition decisions. By anchoring our approach in physiology and clinical evidence, this article aims to transform anticoagulant management from a source of anxiety into a structured, executable component of your emergency practice.

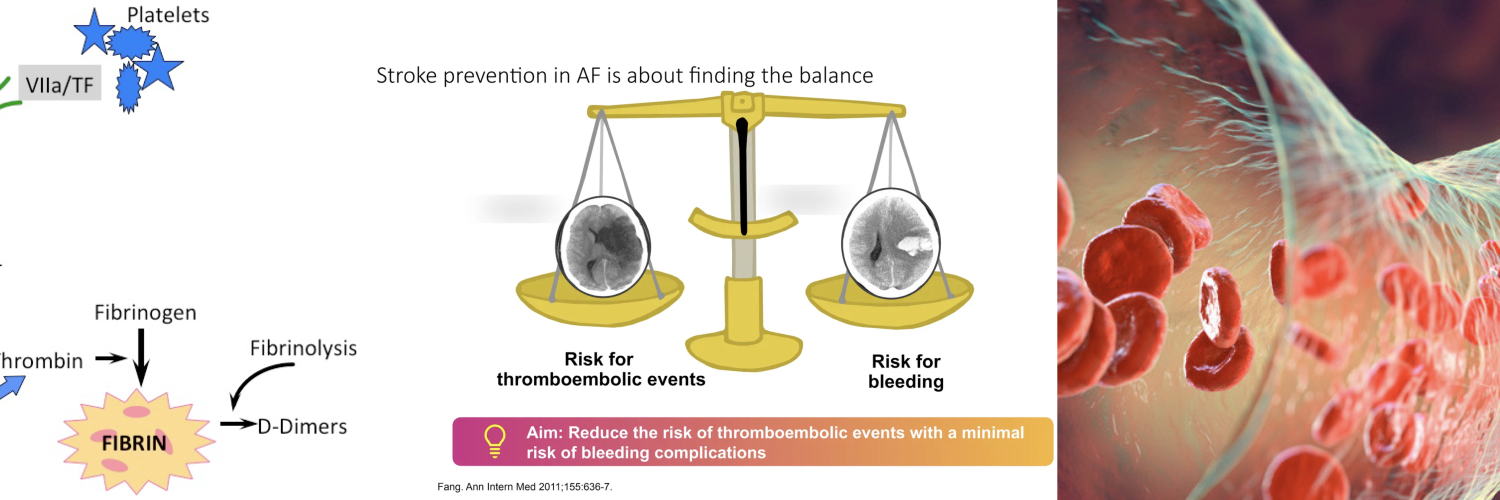

Hemostatic Balance

A Primer for the Emergency Physician

Before we can safely disrupt the clotting system, we must understand the elegant, balanced physiology we are targeting. Normal hemostasis is a self-limiting, localized cascade designed to seal vascular injury without causing systemic thrombosis or excessive bleeding. It operates as a dynamic equilibrium, constantly tipped toward clot formation at sites of injury and toward clot inhibition elsewhere. For the emergency physician, visualizing this balance is key to predicting the effects, and complications of our interventions.

◾️From Physiology to Pathology: Arterial vs. Venous Clots

- This hemostatic system can be dysregulated to form pathologic thrombi, and the type of thrombus dictates the type of drug we use.

- Arterial Thrombi (“White Clots”)

- Form under high shear stress at sites of ruptured atherosclerotic plaque.

- They are platelet-rich, with thin fibrin strands.

- ✅ Both antiplatelets and anticoagulants can be effective for prevention and treatment.

- Venous Thrombi (“Red Clots”)

- Form in low-flow/stasis conditions (e.g., deep veins).

- They are fibrin- and red cell-rich, with a large, loose structure.

- ✅ Anticoagulants are the cornerstone of prevention and treatment; antiplatelets are ineffective.

- Arterial Thrombi (“White Clots”)

- This fundamental difference explains why a patient with atrial fibrillation (a stasis risk) needs an anticoagulant, while a patient with a coronary stent (a platelet-driven risk) needs an antiplatelet. When both risks coexist, we combine therapies, accepting a higher bleeding risk.

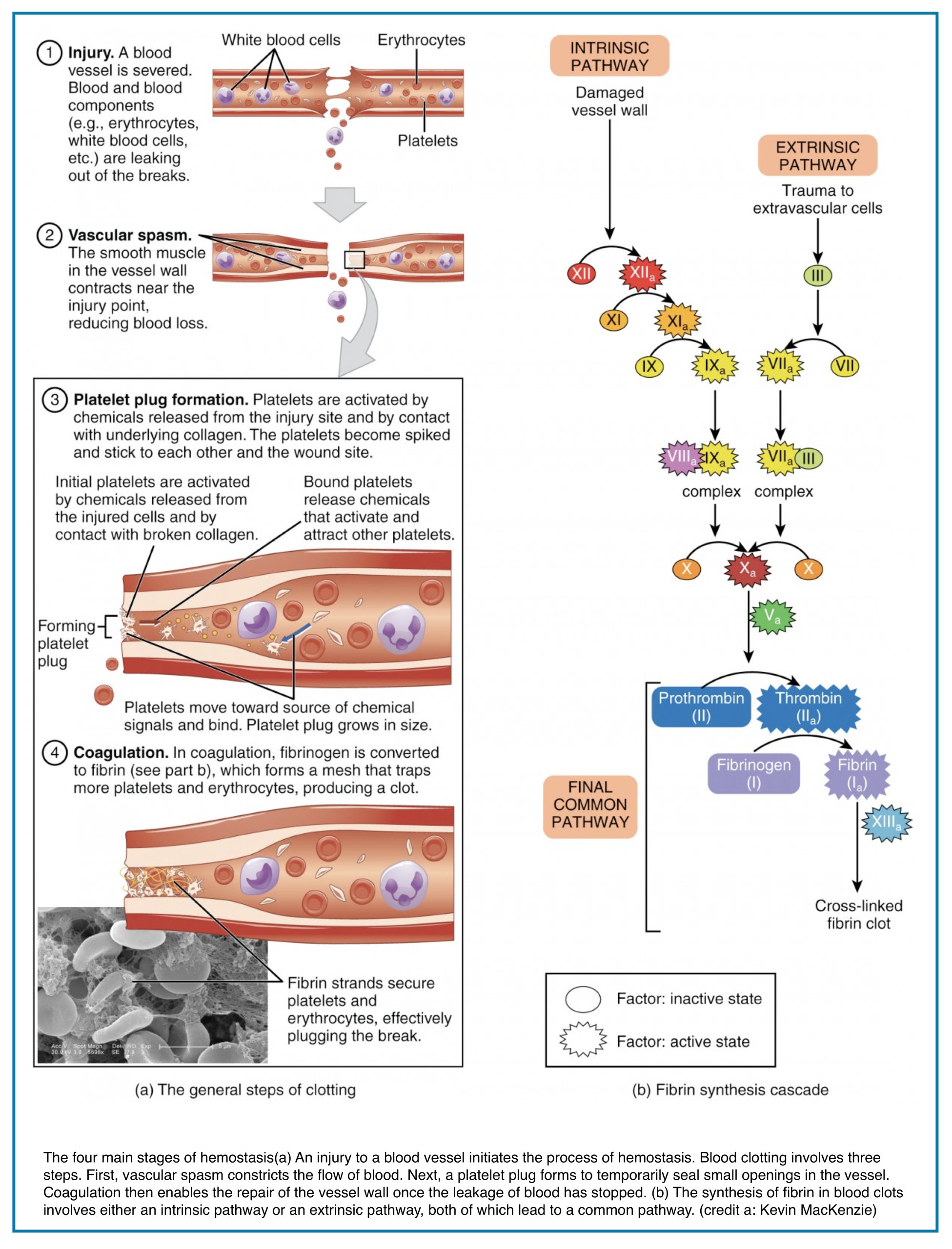

◾️The Four Phases of Hemostasis:

- Vasoconstriction

- Immediate neural and local mediator response to limit blood flow.

- Primary Hemostasis (The “Platelet Plug”)

- Platelets adhere to exposed subendothelial collagen (via von Willebrand Factor), activate, change shape, and aggregate to form a fragile mechanical plug.

- ✅ This is the target of antiplatelet agents (e.g., aspirin, clopidogrel).

- Secondary Hemostasis (The “Fibrin Clot”):

- The coagulation cascade, a series of amplified enzymatic reactions culminating in the conversion of prothrombin (Factor II) to thrombin (IIa).

- Thrombin then converts soluble fibrinogen (I) to insoluble fibrin (Ia), which forms a stabilizing mesh around the platelet plug.

- ✅ This is the target of all anticoagulants (e.g., heparin, warfarin, DOACs).

- Fibrinolysis (The “Clean-Up”)

- Once healing begins, the fibrin clot is broken down by plasmin.

- ✅ This pathway is hijacked by thrombolytic agents (e.g., alteplase/tPA).

◾️Why This Matters in the ED:

- A patient’s bleeding or thrombotic risk is determined by which part of this system is affected by disease or medication.

- A patient on clopidogrel has a deficient platelet plug; one on rivaroxaban has impaired fibrin formation; and a patient receiving tPA has uncontrolled fibrinolysis.

- Catastrophic hemorrhage, such as an intracranial bleed after thrombolysis in a fully anticoagulated patient, occurs when we disrupt multiple pillars of hemostasis simultaneously.

- The following visual summarizes this critical balance, highlighting the specific targets of the pharmacologic agents you will manage.

With this framework in mind, we can now move from physiology to pharmacology, beginning with the first critical step in any encounter: identifying what the patient is taking.

Bleeding Patients

Step 1: Identify the Agent

The first critical task when managing a bleeding patient or initiating therapy is to answer one question: “What specific drug is the patient taking?” This is more challenging than ever, with multiple direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), traditional warfarin, and various injectables. Guessing is not an option.

The Rapid ED Drug Identification Framework

Use this systematic approach to cut through the confusion.

- Ask Directly & Specifically: Don’t just ask, “Are you on blood thinners?” Patients may not consider aspirin or clopidogrel as “blood thinners.” Ask:

- “Are you on medication to prevent strokes or for an irregular heartbeat (like atrial fibrillation)?”

- “Are you on medication for clots in the legs or lungs (DVT or PE)?”

- “Are you on warfarin (Coumadin®), Eliquis®, Xarelto®, Pradaxa®, or Lovenox® shots?”

- Check Available Records: Pull medication lists from the EHR, previous discharge summaries, or pharmacy records. Look for generic names.

- Use a Bedside Clue (For Bleeding Patients): If the patient is on an unknown anticoagulant and bleeding, two rapid tests can provide hints while you await specific assays:

- PT/INR: If markedly elevated (>2.0) → Think Warfarin. (May be mildly elevated with some Factor Xa DOACs).

- aPTT: If prolonged → Could indicate unfractionated heparin, argatroban, or (less reliably) dabigatran.

⚠️ Critical Caution: These are clues only, not diagnostic. A normal INR does not rule out a therapeutic level of a DOAC. When in doubt, treat empirically for major bleeding and consult pharmacy/hematology.

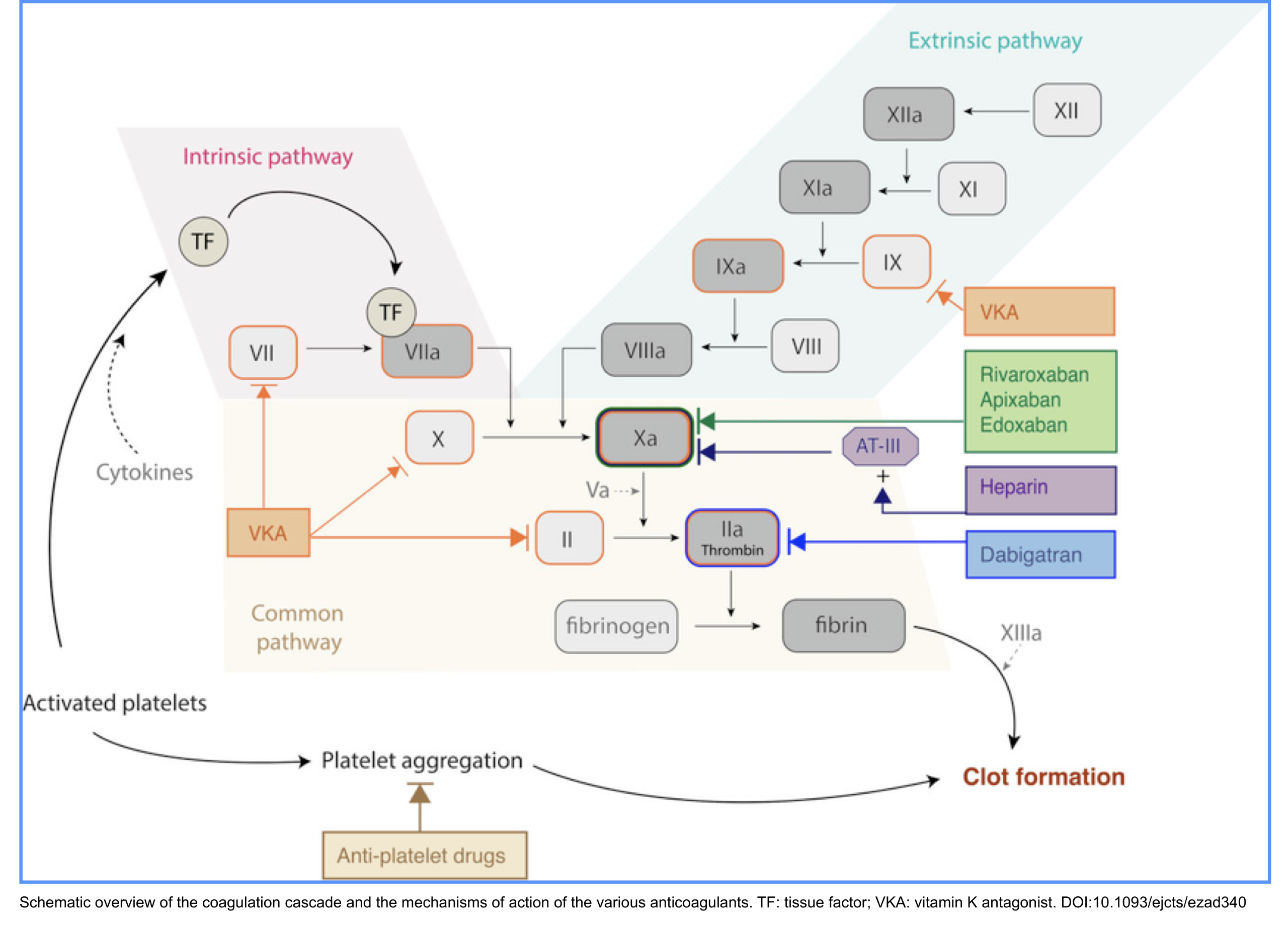

- ⚙️Mechanism of action of anticoagulant: Anticoagulants prevent clotting through different targets * (Figure below)

-

- Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs): Directly bind to the clotting factor.

- Direct thrombin inhibitor: Dabigatran

- Direct Factor Xa inhibitors: Apixaban, Rivaroxaban, Edoxaban

- Indirect Anticoagulants (require antithrombin)

- Inhibit IIa & Xa (via antithrombin): Unfractionated Heparin (UFH)

- Primarily inhibit Xa (via antithrombin): Low Molecular Weight Heparins (Enoxaparin, Dalteparin)

- Selectively inhibit Xa only (via antithrombin): Fondaparinux

- Vitamin K Antagonists (VKAs): Inhibit the synthesis of clotting factors.

- Warfarin, Acenocoumarol

- Direct Thrombin Inhibitors (DTIs – Parenteral): Directly bind to thrombin.

- Bivalirudin, Argatroban

- Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs): Directly bind to the clotting factor.

📊Anticoagulant agents: To streamline identification, use the following reference table.

| Class & Generic Name | Route | Onset | Half-Life | Mechanism | Key Indications | Major Contraindications | Reversal Agent (If Needed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PARENTERAL | Injectable Anticoagulants | ||||||

| Unfractionated Heparin (UFH) | IV, SC | IV: Immediate SC: 2-4h |

1-2h | Activates antithrombin (inhibits IIa, Xa) | • Acute VTE • PCI, cardiac surgery • High-risk PE • Severe renal failure |

• Active major bleeding • HIT (Type II) • Severe thrombocytopenia |

Protamine sulfate (1mg per 100 U UFH) |

| Enoxaparin | SC | 3-5h | 4-7h | Primarily inhibits Factor Xa | • VTE treatment & prophylaxis • ACS (NSTEMI) • Cancer-associated thrombosis |

• Active major bleeding • HIT • Severe renal failure |

Protamine sulfate (partial reversal) PCC may be considered |

| Fondaparinux | SC | 2-3h | 17-21h | Selective indirect Factor Xa inhibitor | • VTE prophylaxis & treatment • HIT (alternative) |

• Active major bleeding • Severe renal failure • Bacterial endocarditis |

No specific antidote PCC or recombinant Factor VIIa may be considered |

| Bivalirudin | IV | Immediate | 25min | Direct thrombin (IIa) inhibitor | • PCI (esp. with HIT) • HIT requiring anticoagulation |

• Active major bleeding | No specific antidote Short half-life allows discontinuation |

| Argatroban | IV | Immediate | 40-50min | Direct thrombin inhibitor | • HIT (diagnosed/suspected) | • Active major bleeding • Severe liver failure |

No specific antidote Short half-life allows discontinuation |

| ORAL | Oral Anticoagulants | ||||||

| Warfarin | PO | 36-72h | 20-60h | Inhibits Vit K-dependent factors (II, VII, IX, X) | • Mechanical heart valves • Antiphospholipid syndrome • Chronic VTE/AF |

• Pregnancy (1st trimester) • Severe liver disease • Uncontrolled bleeding |

• Vitamin K (oral/IV, slow) • 4F-PCC (rapid for major bleeding) |

| Dabigatran | PO | 1-2h | 12-17h | Direct thrombin (IIa) inhibitor | • VTE treatment & prophylaxis • Non-valvular AF |

• Active major bleeding • Severe renal failure • Mechanical heart valves |

Idarucizumab (specific antidote) PCC/APCC if unavailable |

| Rivaroxaban | PO | 2-4h | 5-13h | Direct Factor Xa inhibitor | • VTE treatment & prophylaxis • Non-valvular AF • CAD/PAD |

• Active major bleeding • Severe hepatic disease • Triple-positive APS |

Andexanet alfa (specific antidote) 4F-PCC if unavailable |

| Apixaban | PO | 3-4h | ~12h | Direct Factor Xa inhibitor | • VTE treatment & prophylaxis • Non-valvular AF • High bleed risk patients |

• Active major bleeding • Severe hepatic disease with coagulopathy |

Andexanet alfa (specific antidote) 4F-PCC if unavailable |

| Edoxaban | PO | 1-2h | 10-14h | Direct Factor Xa inhibitor | • VTE treatment • Non-valvular AF |

• Active major bleeding • Severe renal failure |

Andexanet alfa (specific antidote) 4F-PCC if unavailable |

Routes: IV = Intravenous, SC = Subcutaneous, PO = Oral

Key Conditions: HIT = Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia (Type II), Triple-positive APS = Antiphospholipid Syndrome with all three antibodies positive (lupus anticoagulant, anti-cardiolipin, anti-β₂-glycoprotein I).

Reversal Agents: Specific antidotes are preferred when available. PCC = Prothrombin Complex Concentrate (4-factor), APCC = Activated PCC.

General Principle: For major bleeding on any anticoagulant: 1) Stop anticoagulant, 2) Give specific reversal if available, 3) Supportive care (fluids, blood products), 4) Consult Hematology.

Note: This table is for educational reference. Always consult institutional protocols for bleeding management.

Step 2: Managing Major Bleeding

The Reversal Roadmap

When faced with major bleeding in an anticoagulated patient, your management follows two parallel tracks: universal supportive care and drug-specific reversal. Panic is not a plan; a systematic approach is.

◾️The Universal ED Response (For Any Anticoagulant)

- Initiate these actions immediately, concurrently with identifying the agent:

- ABCs & Resuscitation: Secure airway, obtain large-bore IV access, begin balanced resuscitation.

- Call for Help: Activate massive transfusion protocol if indicated. Notify blood bank, pharmacy, and relevant specialists (hematology, interventional radiology, surgery).

- Blood Products: Empirically transfuse as needed:

- Packed Red Blood Cells (PRBCs) for anemia/shock.

- Fresh Frozen Plasma (FFP) or 4-Factor Prothrombin Complex Concentrate (PCC) for general coagulation factor support.

- Platelets if thrombocytopenic or on antiplatelets.

- Tranexamic Acid (TXA) 1g IV for hyperfibrinolysis (consider in all major traumatic bleeds).

- Local Control: Apply direct pressure. Consider topical hemostatic agents. Consult GI, IR, or surgery for procedural control as needed.

◾️Drug-Specific Reversal: From General to Specific

- Once the agent is identified, escalate to targeted therapy. The goal is to restore hemostasis, not necessarily to normalize a lab value.

- For Warfarin (VKA) Over-anticoagulation & Bleeding

- Life-Threatening Bleed (ICH, hemodynamic instability):

- 4-Factor PCC (e.g., Kcentra®) — Dose based on INR and weight. This is the first line for rapid factor replacement (works in minutes).

- IV Vitamin K (5-10 mg) — Co-administer with PCC. It takes 6-24 hours to work but prevents rebound anticoagulation.

- Do NOT use FFP as first-line if PCC is available (slower, volume overload risk).

- Non-Major Bleed or High INR (>4.5) without bleed:

- Hold warfarin.

- Oral or low-dose IV Vitamin K.

- Re-assess and reload warfarin carefully once INR is therapeutic.

- Life-Threatening Bleed (ICH, hemodynamic instability):

- For Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs)

- First, Determine Timing: When was the last dose? If within 2-3 hours, consider activated charcoal if the airway is protected.

- Life-Threatening Bleed:

- For Dabigatran (Direct Thrombin Inhibitor):

- Idarucizumab (Praxbind®) 5g IV x 2. This is the specific, fast-acting antidote. Repeat if re-bleeding occurs.

- For Apixaban/Rivaroxaban/Edoxaban (Factor Xa Inhibitors):

- Andexanet Alfa (Andexxa®) — Weight-based bolus + infusion. This is the specific antidote.

- If Andexanet is unavailable: Use 4-Factor PCC (50 U/kg) as a second-line hemostatic agent (not a true reversal). Do not use FFP.

- For Dabigatran (Direct Thrombin Inhibitor):

- Non-Major Bleed:

- Supportive care. Hold next 1-2 doses. Most DOACs have short half-lives (8-15 hours in normal renal function). Time is an antidote.

- For Heparins & Fondaparinux:

- Unfractionated Heparin (UFH):

- Protamine Sulfate: 1 mg IV per 100 units of UFH given in the previous 2-3 hours. Maximum 50 mg. Infuse slowly (risk of hypotension, anaphylaxis).

- Low Molecular Weight Heparin (e.g., Enoxaparin):

- Protamine Sulfate (Partial Reversal): 1 mg IV per 1 mg of enoxaparin if the last dose was within 8 hours. It reverses anti-IIa activity (~60%) but only partially reverses anti-Xa activity.

- Fondaparinux:

- No specific antidote. Consider recombinant Factor VIIa (rFVIIa) or PCC in catastrophic bleeding, but the evidence is weak. Consult hematology.

- Unfractionated Heparin (UFH):

- Critical Interaction Alert: Concurrent Antiplatelet Therapy

- If the patient is also on aspirin, clopidogrel, etc., bleeding is more severe. Consider platelet transfusion for life-threatening bleeding, especially with recent (<24-48h) intake of irreversible agents like clopidogrel.

- For Warfarin (VKA) Over-anticoagulation & Bleeding

💡 The Reversal Decision Guide

- 📊The following table summarizes this critical pathway for rapid reference.

- The most important question is: “Is this bleed immediately life-threatening (ICH, compartment syndrome, hemodynamic instability)?”

- If YES, move to specific reversal immediately.

- If NO, time and supportive care may suffice.

| Anticoagulant Class & Agent | Reversal Strategy | Specific Agent & Dose | Onset / Duration | Key ED Considerations & Pearls |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin K Antagonists Warfarin |

Specific + Nonspecific |

1. 4-Factor PCC (Kcentra®) • Dose: INR-based (25-50 U/kg) 2. IV Vitamin K • 5-10 mg slow IV infusion |

• PCC: Immediate • Vit K: 6-24h |

• For life-threatening bleeds: Give PCC + IV Vitamin K together. • Do NOT use FFP first-line if PCC available (slower, volume overload). • IV Vitamin K prevents “rebound” anticoagulation after PCC wears off. |

| Direct Thrombin Inhibitor Dabigatran |

Specific Antidote |

Idarucizumab (Praxbind®) • 5g IV (2 vials of 2.5g) Second-line: PCC/APCC (if unavailable) |

• Idarucizumab: Immediate (~5 min) • Duration: ~24h |

• First-line for major bleeding. Repeat dose if re-bleeding. • Check aPTT/dTT pre/post (but don’t delay treatment for lab). • Consider activated charcoal if last dose within 2-3h & protected airway. |

| Factor Xa Inhibitors Apixaban, Rivaroxaban, Edoxaban |

Specific Antidote |

Andexanet Alfa (Andexxa®) • Low dose: 400 mg bolus + 480 mg infusion • High dose: 800 mg bolus + 960 mg infusion Second-line: 4-Factor PCC (50 U/kg) |

• Andexanet: Immediate (bolus) • Duration: ~2h after infusion ends |

• Low dose if last dose <8h or unknown. • High dose if last dose ≥8h or with life-threatening bleed. • Thrombotic risk: Consider heparin bridging 12-24h post-reversal. • Very expensive—confirm insurance/hospital protocol. |

| Unfractionated Heparin (IV UFH) |

Specific Antidote |

Protamine Sulfate • 1 mg per 100 U of UFH • Max 50 mg • Give slow IV (over 10 min) |

• Immediate • Duration: ~2h |

• Only reverse UFH given in last 2-3 hours. • Infuse slowly—risk of hypotension, bradycardia, anaphylaxis. • Monitor aPTT 5-15 min after completion. • Consider partial reversal (0.5 mg/100 U) if borderline bleed. |

| Low Molecular Weight Heparin Enoxaparin, Dalteparin |

Partial Reversal |

Protamine Sulfate • 1 mg per 1 mg enoxaparin • If >8h since dose, give 0.5 mg per 1 mg |

• Immediate • Partial effect only |

• Only partially effective (~60% anti-IIa reversal, minimal anti-Xa). • Consider rFVIIa or PCC for catastrophic bleed despite protamine. • Check anti-Xa level if available (not to guide reversal, but to assess burden). |

| Selective Factor Xa Inhibitor Fondaparinux |

No Specific Antidote |

• rFVIIa (90 mcg/kg) • PCC (50 U/kg) (Limited evidence) |

• Variable • Weak evidence |

• Consult hematology immediately. • rFVIIa or PCC may be considered in catastrophic bleeding. • Long half-life (17-21h)—bleeding risk prolonged. • Renal clearance—avoid in CrCl <30. |

| DTI (Parenteral) Argatroban, Bivalirudin |

Discontinuation + Time |

• Stop infusion • Supportive care • Consider dialysis for bivalirudin (extracorporeal removal) |

• Argatroban: 2-4h • Bivalirudin: 25 min |

• Short half-lives—discontinuation is primary strategy. • Monitor aPTT. • For bivalirudin in renal failure, consider emergent dialysis. • No proven benefit of PCC/rFVIIa (case reports only). |

Before Specific Reversal: Always start with ABCs, resuscitation, and local control. Specific reversal is adjunctive, not a substitute for good supportive care.

Key Abbreviations: PCC = Prothrombin Complex Concentrate, APCC = Activated PCC, rFVIIa = recombinant Factor VIIa, DTI = Direct Thrombin Inhibitor, UFH = Unfractionated Heparin.

Critical Pearl: For life-threatening bleeds (ICH, hemodynamic instability), give the specific antidote first if available. For non-major bleeds, time and supportive care may be sufficient given short half-lives of most agents.

⚠️ Always consult your hospital’s pharmacy and hematology for latest protocols.

📍Bottom Line for the EP: Your first moves are universal resuscitation + rapid drug ID. Your next move is targeted reversal based on that ID. With this roadmap, you can approach even the most intimidating bleeding scenario with a clear, life-saving plan.

Patients with thrombosis

When to Start Anticoagulants in the ED

A. Therapeutic Anticoagulation

The decision to initiate therapeutic anticoagulation in the ED for a newly diagnosed thrombotic event requires balancing urgent benefit against immediate risk. The primary goal is to prevent clot extension, embolization, and recurrence, while minimizing major bleeding, a concern that is particularly heightened in unstable patients or those undergoing planned procedural intervention. For many stable patients, timely ED initiation facilitates effective treatment and allows for safe outpatient management.

⎮The decision to initiate therapeutic anticoagulation requires accepting some bleeding risk to manage the immediate threat of thrombosis.

📍Key Indications to Start Therapeutic Anticoagulation in the ED (Anticoagulant-Naïve Patient)

- Acute Venous Thromboembolism (PE/DVT)

- Hemodynamically stable PE or DVT.

- Acute Arterial Thromboembolism

- Limb Ischemia

- Guidelines support immediate systemic anticoagulation with UFH as a bridge to definitive revascularization (surgery/thrombectomy).

- Ischemic Stroke: Anticoagulation is NOT indicated acutely for most strokes (risk of hemorrhagic transformation). Initiation is indicated for specific scenarios:

- Cardioembolic Stroke (e.g., AFib): Typically started 2-14 days post-stroke based on infarct size and bleeding risk.

- Cerebral Venous Thrombosis (CVT): Therapeutic anticoagulation (UFH/LMWH) is first-line, even with hemorrhagic infarction.

- Limb Ischemia

- Unstable Cardiac Conditions

- STEMI / High-Risk NSTEMI: As part of the ACS protocol (e.g., IV heparin/enoxaparin) while arranging for coronary revascularization (PCI/CABG).

- AFib/Flutter with RVR with Urgent Need for Cardioversion

- Scenario: AFib with RVR causing acute heart failure, ischemia, or hypotension, where immediate cardioversion is planned.

- Action: If therapeutic for <3 weeks and no time for TEE, give parenteral anticoagulant (UFH/LMWH) immediately pre- and post-cardioversion.

- Intracardiac Thrombus

- Scenario: Newly identified mobile left ventricular (LV) thrombus post-MI, or left atrial/atrial appendage thrombus in a patient with embolic symptoms.

- Action: Start therapeutic anticoagulation (typically warfarin or DOAC based on etiology).

- Bridging Therapy

- Starting therapeutic-dose LMWH for a high-risk patient (e.g., mechanical mitral valve, recent VTE) who must hold their warfarin for an urgent procedure.

- Special High-Stakes Scenarios (Disease-Specific)

- Antiphospholipid Syndrome (APLS) with Acute Thrombosis

- Scenario: New arterial or venous thrombosis in a patient with known or suspected APLS.

- Critical Action: Start heparin (UFH/LMWH) bridge to warfarin.

- DOACs are not first-line and may be contraindicated in high-risk APLS.

- Antiphospholipid Syndrome (APLS) with Acute Thrombosis

🚫Crucial “DO NOT START” Exceptions in the ED

- New, Stable Atrial Fibrillation: Initiation of lifelong therapy is an outpatient decision.

- Acute Ischemic Stroke (Most Cases): Therapeutic anticoagulation is delayed (typically 2-14 days) due to risk of hemorrhagic transformation.

- Low-Risk DVT (e.g., isolated distal calf DVT): May be managed with monitoring or prophylactic dose, not full therapeutic anticoagulation, per guidelines.

B. Prophylactic Initiation of Anticoagulation in ED

The decision to initiate prophylactic anticoagulation in the ED aims to prevent future thrombotic events in at-risk patients. This differs from the treatment of an acute clot. ED initiation is safe and effective when patient selection is guided by validated risk scores and clear follow-up. Prophylaxis primarily falls into two categories: stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation (AF) and venous thromboembolism (VTE) prevention in high-risk immobilized patients.

⎮The decision to initiate prophylactic anticoagulation demands a conservative approach, as the benefit is preventive and not immediate.

📍Key Indications for Prophylactic Anticoagulation in the ED

- For Stroke Prophylaxis in New Atrial Fibrillation/Flutter

- For newly diagnosed AF/flutter, the goal is long-term stroke risk reduction. ED initiation is appropriate for selected patients to bridge the care gap.

- Thrombotic Risk: CHA₂DS₂-VASc score ≥ 2 (men) or ≥ 3 (women). 🧮MDCalc

- Bleeding Risk: Low to moderate (e.g., HAS-BLED score ≤ 2, no active or high-risk lesions). 🧮MDCalc

- ED Role: Initiate low-dose prophylactic anticoagulation (e.g., enoxaparin 40 mg SC daily, rivaroxaban 10 mg daily) if the risk of VTE outweighs the bleeding risk and the anticipated hospitalization or immobility will continue. This is not therapeutic dosing.

- Key to Discharge: Established follow-up with primary care or cardiology must be secured. The first dose is often given in the ED after shared decision-making.

- For newly diagnosed AF/flutter, the goal is long-term stroke risk reduction. ED initiation is appropriate for selected patients to bridge the care gap.

- For VTE Prophylaxis in High-Risk Patients

- Initiation of pharmacologic prophylaxis is considered in high-risk medical or trauma patients being admitted or placed in observation.

- Acutely Ill Medical Patients being hospitalized, particularly those with a high IMPROVE VTE Risk Score (e.g., ≥ 2 points). High-risk features in this score include:

- Prior VTE

- Known thrombophilia

- Active cancer

- ICU/CCU stay

- Lower limb paralysis

- AND significantly reduced mobility (bedrest for ≥ 7 days).

- Major Trauma Patients (without major active bleeding or intracranial injury) with:

- Spinal cord injury.

- Major pelvic or long bone fractures.

- Multiple system trauma.

- Acutely Ill Medical Patients being hospitalized, particularly those with a high IMPROVE VTE Risk Score (e.g., ≥ 2 points). High-risk features in this score include:

- Initiation of pharmacologic prophylaxis is considered in high-risk medical or trauma patients being admitted or placed in observation.

-

-

- Patients Requiring Immobilization (e.g., non-weight-bearing orthopedic injuries) who have additional VTE risk factors (age > 60, prior VTE, known thrombophilia).

-

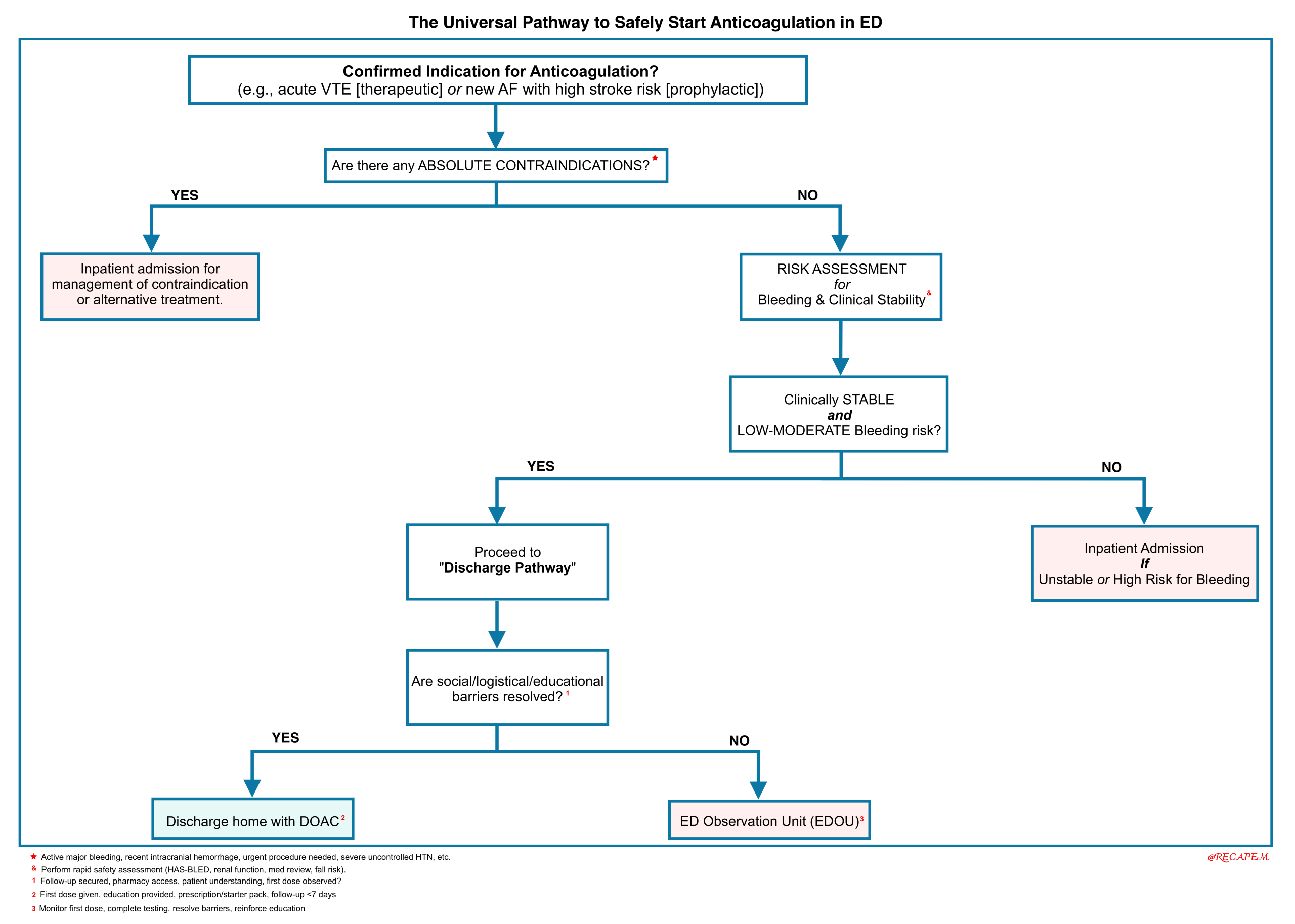

Universal ED Anticoagulation Initiation Pathway

From Decision to Action

Whether initiating anticoagulation for a new thrombus or for long-term prophylaxis, the practical steps to ensure patient safety are consistent. The following universal pathway synthesizes the key indications above into a single, actionable checklist for the emergency physician. It guides you through the critical safety assessments, ruling out absolute contraindications, evaluating bleeding risk, and ensuring the stable disposition required before administering the first dose.

Right Risk-Assessment

Initiation should be considered immediately upon confirmation of an indication (e.g., acute VTE) and completion of a rapid, structured dual-risk assessment. This assessment must occur before the first dose and is the cornerstone of safe prescribing. The decision to anticoagulate is based on the net clinical benefit, where the estimated thromboembolic risk significantly outweighs the projected bleeding risk.

The Risk Assessment includes:

- Thromboembolic Risk Stratification: Calculate a validated risk score specific to the indication to quantify the risk of stroke, systemic embolism, or VTE recurrence if untreated *.

- Bleeding Risk Stratification: Calculate a validated bleeding risk score to identify modifiable risk factors and quantify the baseline hazard of therapy.

- Review of Organ Function & Comorbidities: Point-of-care renal function (serum creatinine/eGFR), hepatic function, complete blood count, and a focused history for high-risk lesions, recent trauma/surgery, and fall risk.

- Review of Concomitant Medications: Screen for drug-drug interactions (e.g., antiplatelets, NSAIDs, strong P-gp/CYP inducers or inhibitors).

⎮There is no benefit to delaying therapy for stable patients once this assessment is complete. Delays increase the period of unprotected thromboembolic risk without mitigating bleeding risk.

Selecting the Right Risk-Assessment Tool

Initiating anticoagulation safely requires answering two risk questions: “What is this patient’s thrombotic risk?” and “What is their bleeding risk?”

Thrombotic Risk Stratification Tools

These tools quantify the thrombotic burden for specific indications. Use them to determine which patients derive a clear net clinical benefit from anticoagulation therapy.

📊Thrombotic Risk Assessment Tools

| Primary Indication | Thromboembolic Risk Tool | Key Components & Interpretation | Bleeding Risk Tool | Key Components & Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atrial Fibrillation (Stroke Prevention) | ||||

| Non-Valvular AF | CHA₂DS₂-VASc |

Components: CHF, HTN, Age≥75 (2p), Diabetes, Stroke/TIA (2p), Vascular disease, Age 65-74, Female sex.

Score Range: 0-9

Action Threshold: ≥2 in men, ≥3 in women → Anticoagulation indicated

Score of 1 (men) or 2 (women): Consider based on patient preference & other factors.

|

HAS-BLED |

Components: HTN, Abnormal renal/liver, Stroke, Bleeding history, Labile INR, Elderly>65, Drugs/EtOH.

Score Range: 0-9

Score ≥3 indicates high bleeding risk

Not a contraindication—flag to correct modifiable factors (BP, EtOH) & monitor closely.

|

| Valvular AF / Alternative | R2CHADS2 |

Used for rheumatic mitral valve disease. Adds “R” (rheumatic heart disease) to CHADS₂.

For mitral stenosis or mechanical valves, warfarin is required regardless of score.

|

ORBIT |

Components: Older age, Reduced Hb/Hct, Bleeding history, Insufficient renal function, Treatment with antiplatelet.

Score Range: 0-7

Simpler than HAS-BLED. Validated in AF populations. Score ≥4 indicates high risk.

|

| Venous Thromboembolism (PE & DVT) | ||||

| Pulmonary Embolism | PESI / sPESI |

Components (sPESI): Age>80, Cancer, Chronic HF/Resp Dz, HR≥110, SBP<100, O₂ sat<90%.

sPESI = 0 → Low mortality risk, candidate for outpatient treatment

sPESI ≥1 → Higher risk, consider hospitalization

|

VTE-BLEED |

Components: Active cancer, male with uncontrolled HTN, anemia, bleeding history, renal dysfunction, age ≥60, prior stroke, PE (vs DVT).

Designed for VTE patients on DOACs. Score ≥2 suggests high bleeding risk during extended therapy.

|

| Diagnosis & Recurrence | D-Dimer + Wells/Geneva |

Used for diagnosis & assessing recurrence risk.

Negative D-Dimer + low clinical probability can rule out PE/DVT. Positive D-Dimer + high probability warrants imaging & treatment.

|

HAS-BLED / RIETE |

HAS-BLED often applied to VTE.

RIETE registry score: recent major bleeding, creatinine >1.2 mg/dL, anemia, cancer, symptomatic PE.

RIETE score >2.5 indicates high bleeding risk.

|

| Acute Coronary Syndrome / Post-PCI (DAPT Decisions) | ||||

| Bleeding Risk for DAPT Duration | PRECISE-DAPT |

Components: Age, creatinine clearance, Hb, WBC, prior bleeding.

Score Range: 0-100

Score ≥25 suggests high bleeding risk

Favors shorter DAPT duration (3-6 months) after PCI.

|

CRUSADE |

Components: Baseline Hct, CrCl, HR, SBP, sex, signs of HF, diabetes, prior vascular disease.

Predicts in-hospital major bleeding risk for ACS patients. Higher scores warrant careful antithrombotic dosing & monitoring.

|

| Ischemic vs. Bleeding Balance | DAPT Score |

Estimates ischemic benefit vs. bleeding risk of extending DAPT beyond 1 year.

Score ≥2 favors extended therapy

Score ≤1 favors discontinuation at 1 year

|

ARC-HBR |

Consensus definition of high bleeding risk for PCI patients.

Criteria: oral anticoagulation use, severe CKD, anemia, prior major bleed, etc. Guides stent choice & DAPT duration.

|

🩸Bleeding Risk Assessment Tools

Bleeding risk scores estimate the baseline hazard of therapy. They are best used to identify and correct modifiable risk factors (e.g., uncontrolled HTN, concomitant NSAIDs) and to determine the intensity of follow-up. A high score is a flag for caution, not an absolute contraindication. The following table compares the most widely used bleeding risk assessment tools to guide clinician selection and interpretation at the point of care.

⎮A crucial point: A high bleeding risk score often calls for modifiable risk factor correction and increased monitoring, not outright denial of necessary anticoagulation.

📊Bleeding Risk Assessment Tools

| Score Name | Primary Use | Components (Points) | Risk Stratification | Major Bleed Risk | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAS-BLED (Most Common) |

Atrial Fibrillation on AC |

Hypertension (uncontrolled, +1) Abnormal Renal/Liver function (+1 each) Stroke (prior, +1) Bleeding history/predisposition (+1) Labile INR (+1) Elderly (>65, +1) Drugs/Alcohol (+1 each) |

0-2: Low ≥3: High |

~1%/yr (Low) ~4-6%/yr (High) |

NOT to withhold AC, but to identify & correct modifiable risks (control HTN, reduce alcohol, review meds). High score → more frequent monitoring. |

| ATRIA | Atrial Fibrillation |

• Anemia (+3) • Severe renal disease (eGFR <30, +3) • Age ≥75 (+2) • Prior bleeding (+1) • Hypertension (+1) |

0-3: Low 4: Intermediate 5-10: High |

0.4%/yr (Low) 2.4%/yr (High) |

Weighs anemia & renal disease heavily. Validated in large community cohorts. Useful for discussing realistic bleed risk with patients. |

| VTE-BLEED | VTE on AC (Extended Therapy) |

• Active cancer (+2) • Prior bleeding (+2) • Age ≥60 (men) / ≥65 (women) (+1.5) • Renal impairment (+1.5) • Anemia (Hct <30%) (+1.5) • PE (vs DVT) as index event (+1) • Heavy alcohol use (+1) |

0-2: Low ≥3: High |

~2% at 1yr (Low) ~12% at 1yr (High) |

Helps decide duration of AC after first 3 months. High score may favor shorter treatment (3-6 months) over indefinite therapy for unprovoked VTE. |

| RIETE | VTE (during treatment) |

• Recent major bleeding (+2) • Creatinine >1.2 mg/dL (+1.5) • Anemia (Hgb <13 g/dL men, <12 women) (+1.5) • Clinically overt PE (+1) • Age >75 (+1) • Cancer (+1) |

0: Low 1-4: Intermediate >4: High |

0.3% at 3mo (Low) 10% at 3mo (High) |

Predicts early bleeding risk during initial VTE treatment. Useful for initial patient counseling and monitoring intensity. |

| IMPROVE | Medical Inpatients (VTE Prophylaxis) |

• Active cancer (+1) • Prior bleed (+1.5) • Renal failure (+1) • Age >85 (+1) • ICU/CCU stay (+1) • Hepatic failure (+1) • Central venous catheter (+1) • Rheumatic disease (+1) • Male sex (+1) |

0-1: Low ≥2: High |

~0.7% (Low) ~4.5% (High) |

Assesses bleeding risk to guide VTE prophylaxis decisions in hospitalized medical patients. High score may favor mechanical over pharmacologic prophylaxis. |

| ABC-Bleeding | ACS/PCI on DAPT |

• Age (+1 per 10y >30) • Bleeding history (+2) • Cancer (+1) • GFR <60 (+1) • Platelet count <200k (+1) • Use of anticoagulation (+1) • Anemia (Hgb <13 men, <12 women) (+1) |

<10: Low 10-14: Intermediate ≥15: High |

~1% (Low) ~5% (High) at 1yr |

Used in cardiology for patients on dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) post-PCI. Guides DAPT duration (shorter for high bleed risk). |

| ORBIT-AF | Atrial Fibrillation |

• Age >74 (+1) • Bleeding history (+2) • GFR <60 (+1) • Hemoglobin <13 (men) / <12 (women) (+1) • Treatment with antiplatelet (+1) |

0-2: Low 3: Intermediate ≥4: High |

0.8%/yr (Low) 5.8%/yr (High) |

Simpler than HAS-BLED, emphasizes anemia and antiplatelet use. Well-validated in AF registry data. |

Choosing the Right Score:

• For Atrial Fibrillation: Start with HAS-BLED (most common) or ORBIT-AF (simpler).

• For VTE Treatment Duration: Use VTE-BLEED at 3-month decision point.

• For Hospitalized Patients: Use IMPROVE for prophylaxis decisions.

• For Post-PCI on DAPT: Use ABC-Bleeding.

Critical Pearls:

1. High bleeding risk ≠ No anticoagulation. It means: “Correct modifiable factors, choose safer agent (e.g., DOAC over warfarin), monitor closely.”

2. HAS-BLED ≥3: Do NOT withhold anticoagulation for AF. Correct risks (control BP, reduce alcohol) and anticoagulate.

3. Scores estimate relative risk. Combine with clinical judgment (fall risk, occult GI lesions, compliance).

4. Re-assess bleeding risk regularly (after hospitalizations, new diagnoses).

Abbreviations: AC = Anticoagulation, AF = Atrial Fibrillation, VTE = Venous Thromboembolism, DVT = Deep Vein Thrombosis, PE = Pulmonary Embolism, DAPT = Dual Antiplatelet Therapy, PCI = Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, ACS = Acute Coronary Syndrome, HTN = Hypertension, GFR = Glomerular Filtration Rate, Hct = Hematocrit, Hgb = Hemoglobin.

Patient Disposition Pathways

The final step of the initiation pathway requires determining the safest setting for the first doses of therapy and monitoring. The following criteria guide the choice between discharge, observation, and admission.

Disposition is determined by clinical stability, bleeding risk, and system/social factors.

1. Safe Discharge Home with DOAC Prescription

- Candidate Profile

- Clinically stable patient with a clear indication, low-to-moderate bleeding risk (e.g., HAS-BLED ≤3), normal renal function, no active high-risk features, demonstrated understanding of therapy, and a reliable plan for follow-up and medication access.

- ED Actions

- Provide the first dose in the ED under observation if feasible.

- Issue a complete prescription with clear instructions. The use of “starter packs” or a direct-dispense model from the ED pharmacy is highly encouraged to ensure immediate access.

- Deliver structured, verbal, and written education on the drug name, dose, timing, indications, signs of bleeding and thrombosis, and drug interactions.

- Arrange and communicate a specific follow-up plan (e.g., with primary care, cardiology, or an anticoagulation clinic) within 3-7 days.

2. Management in an Emergency Department Observation Unit (EDOU)

- Candidate Profile: Patients who are not immediate discharge candidates but do not require inpatient resources. This includes those with:

- Moderate or unclear bleeding risk needing short-term monitoring after the first dose.

- Social or logistical barriers (e.g., unable to fill a prescription until morning).

- Need for further diagnostic clarification (e.g., echocardiogram) that can be obtained within 24 hours.

- Complex medication reconciliation or requirement for multidisciplinary planning (e.g., social work, pharmacy consultation).

- ED/EDOU Actions: Allows for the first 1-2 doses to be administered under monitoring, completion of ancillary tests, reinforcement of education, and confirmation of follow-up plans, facilitating safe discharge within 24 hours.

3. Inpatient Hospital Admission

- ⚠️Indications: Admission is warranted for patients with:

- Absolute contraindications to immediate anticoagulation (see below).

- High bleeding risk requiring procedural intervention before anticoagulation (e.g., need for urgent surgery, endoscopic evaluation of a GI bleed).

- Clinical instability related to the arrhythmia or comorbidities (e.g., heart failure exacerbation, acute coronary syndrome).

- Life-threatening complications of thrombosis (e.g., hemodynamically significant PE, stroke).

- Severe renal/hepatic impairment requiring complex dosing or alternative management.

⎮🚫 Absolute Contraindications to ED Initiation. A clear “stop” rule is essential. Do not initiate in the ED if the patient has:

- Active, clinically significant bleeding (meeting criteria for major bleeding).

- Known or suspected intracranial pathology at high risk for bleeding (recent stroke, aneurysm, AVM, primary or metastatic brain cancer).

- Recent major trauma, surgery (within 48-72 hours), or spinal puncture.

- Severe, uncontrolled hypertension (e.g., systolic BP >200 mmHg).

- Documented hypersensitivity to the chosen agent.

- Pregnancy (for most DOACs).

📍Conclusion: For the majority of stable ED patients with a clear indication for anticoagulation, initiation in the ED is safe, effective, and aligns with the goal of timely stroke prevention. A structured approach using risk stratification to guide disposition—favoring discharge with robust support—can improve patient outcomes and optimize healthcare resource utilization. The subsequent section will detail the essential components of patient education and follow-up coordination required to ensure the safety of this approach beyond the ED doors.

Ensuring Safe Follow-Through

Initiating anticoagulation is only the first step. Safe outcomes depend on vigilant clinical monitoring and seamless care coordination.

A. Clinical & Laboratory Monitoring

Routine lab monitoring is not required for DOACs in stable patients with normal renal function. Monitoring is essential for parenteral agents and warfarin, and to detect critical complications like HIT.

Key Labs & Intervals:

- Warfarin: INR at least twice weekly until stable, then periodically.

- UFH (IV): aPTT every 6 hours after dose change, then every 24 hrs once therapeutic.

- LMWH (Enoxaparin): Anti-Xa level (peak) only in special populations (morbid obesity, renal failure, pregnancy).

- Routine for All: Baseline creatinine/eGFR, CBC, LFTs. Repeat based on agent stability and clinical course.

🔬Anticoagulants that require routine monitoring of specific laboratory parameters:

- 🔎Routine monitoring is mandatory only for IV UFH (aPTT) and Warfarin (INR).

- ✅DOACs and prophylactic LMWH are designed for fixed dosing without monitoring.

- ⚠️Special situations (renal failure, pregnancy, extremes of size) shift LMWH and sometimes DOACs into the “monitor with Anti-Xa or drug level” category.

💡This “monitor vs. no monitor” distinction is a key practical advantage of DOACs over warfarin in outpatient care.

📊The following table compares Warfarin, DOACs, LMWH, etc., on parameters like routine monitoring test, monitoring frequency, key parameters to track [renal function, liver function, CBC, signs of bleeding], and special notes.

| Anticoagulant | Monitoring Required? | Parameter to Monitor | Target Range | Frequency | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| REQUIRES ROUTINE LABORATORY MONITORING | |||||

| Unfractionated Heparin (UFH) IV infusion |

YES (Mandatory) |

aPTT or Anti-Factor Xa | aPTT: 1.5-2.5x control Anti-Xa: 0.3-0.7 IU/mL |

Check 6h after start/dose change, then at least daily. | Unpredictable dose-response. Monitoring ensures efficacy and prevents bleeding. |

| Warfarin | YES (Mandatory) |

INR (International Normalized Ratio) |

Standard: 2.0-3.0 High-Risk: 2.5-3.5 (e.g., mechanical mitral valve) |

Daily at initiation, then every 1-4 weeks once stable. | Numerous drug/food interactions. INR reflects effect on Vitamin K factors; critical for safety. |

| Direct Thrombin Inhibitors IV (Argatroban, Bivalirudin) |

YES (During infusion) |

aPTT | 1.5-2.5x patient’s baseline | Check 2h after start, then per institutional protocol (often q4-6h). | To ensure therapeutic anticoagulation during acute treatment (e.g., HIT, PCI). |

| NO ROUTINE MONITORING (Fixed Dosing) | |||||

| DOACs Apixaban, Rivaroxaban, Edoxaban, Dabigatran |

NO (Routine) |

None | N/A | N/A | Predictable pharmacokinetics. Given at fixed/weight-based doses. |

| LMWH Enoxaparin, Dalteparin (Standard Prophylaxis/Treatment) |

NO (Routine) |

None | N/A | N/A | Predictable anti-Xa effect with weight-based dosing in normal renal function. |

| Fondaparinux | NO | None | N/A | N/A | Predictable pharmacokinetics with fixed weight-based dosing. |

| Special Circumstance | Anticoagulant(s) Affected | Consider Monitoring | Clinical Rationale & Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Severe Renal Impairment (CrCl <30 mL/min) |

• LMWH (Enoxaparin) • Dabigatran, Edoxaban |

YES (Anti-Xa or drug level) |

Renal clearance is significantly reduced → risk of drug accumulation and bleeding. LMWH: Monitor peak Anti-Xa (3-5h post-dose). DOACs: Avoid or use with extreme caution; check trough level if used. |

| Pregnancy | LMWH (Drug of choice) | YES (Anti-Xa level) |

Pharmacokinetics change throughout pregnancy (increased renal clearance, volume of distribution). Check peak Anti-Xa monthly and trimestrally to ensure therapeutic dose. |

| Morbid Obesity (>120 kg) or Low Weight (<50 kg) | • LMWH • UFH |

YES (Anti-Xa level) |

Standard weight-based dosing may be inaccurate at extremes of body size. Use Anti-Xa monitoring to guide dose adjustment. |

| Bleeding or Emergency Surgery | All, especially DOACs | YES (Drug-specific assay if available) |

To guide reversal therapy. For DOACs, use drug-specific calibrated Anti-Xa assay (for Xa inhibitors) or diluted TT/ECT (for dabigatran). Also check standard CBC, PT/INR, aPTT, fibrinogen. |

| Suspected Treatment Failure (e.g., Recurrent Clot) |

Any, particularly DOACs | YES (Trough drug level) |

To assess compliance and rule out sub-therapeutic drug levels due to interactions, malabsorption, or extreme metabolism. |

Parameter Key: aPTT = Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time, INR = International Normalized Ratio, Anti-Xa = Anti-Factor Xa level.

Rule of Thumb: Routine monitoring is mandatory only for warfarin (INR) and therapeutic IV UFH (aPTT/Anti-Xa). This is a major practical advantage of DOACs and LMWH in stable outpatients.

DOAC Levels: While not routine, drug-specific levels can be measured in specialized labs and are useful in the special circumstances listed above.

LMWH in Renal Failure: This is a critical exception—always monitor Anti-Xa levels when using LMWH in patients with CrCl <30 mL/min.

Critical Heparin-Specific Monitoring Alerts

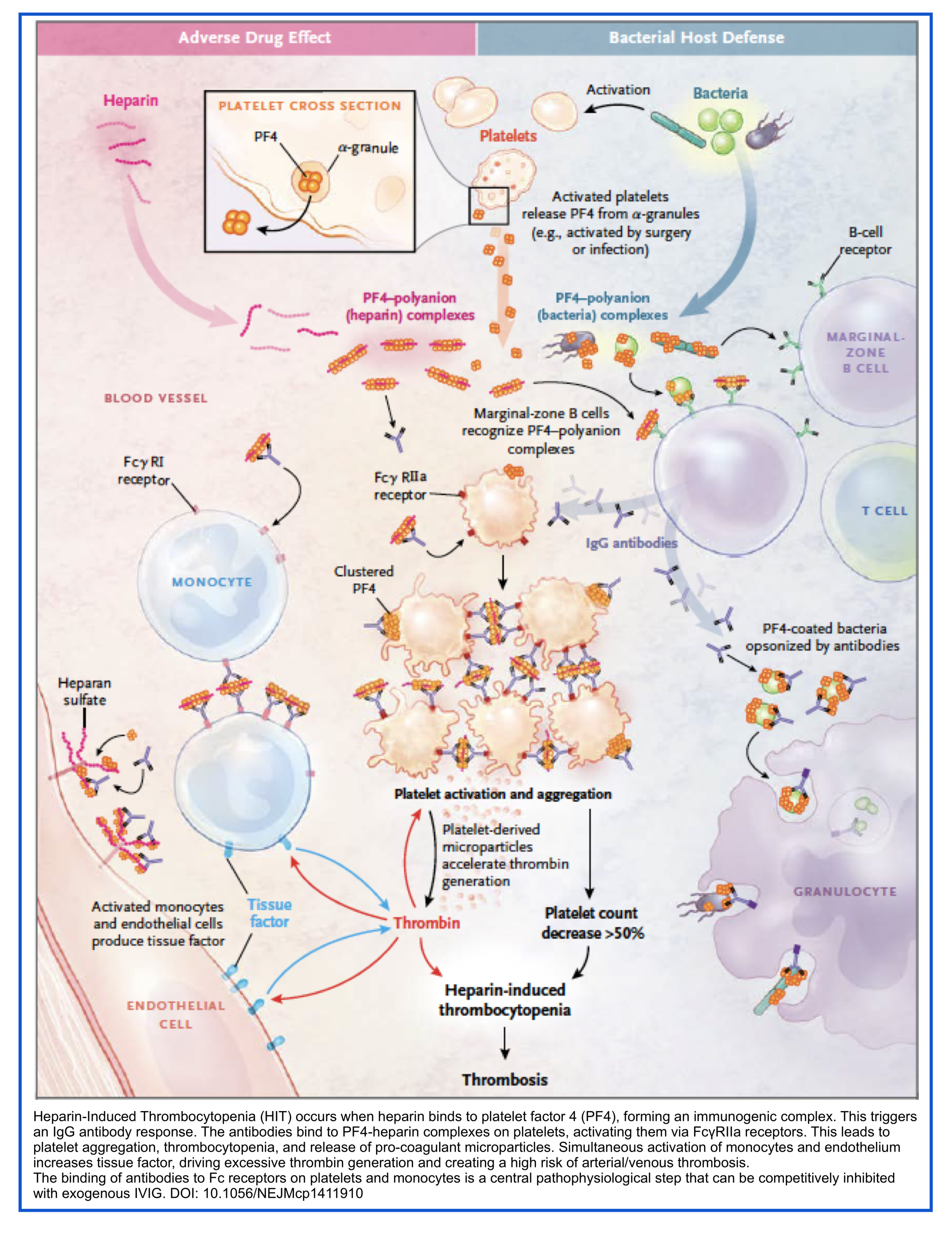

1. Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia (HIT)

◾️Definition:

-

Immune‑mediated pro‑thrombotic disorder caused by IgG antibodies against platelet factor‑4 (PF4)/heparin complexes, leading to platelet activation, thrombocytopenia, and high risk of arterial/venous thrombosis.

◾️Epidemiology & Risk Factors:

- Highest risk: Surgical ICU (especially cardiac/orthopedic), therapeutic‑dose UFH, female sex, >5 days of heparin exposure.

- LMWH is lower risk than UFH; avoid UFH when possible to reduce HIT incidence.

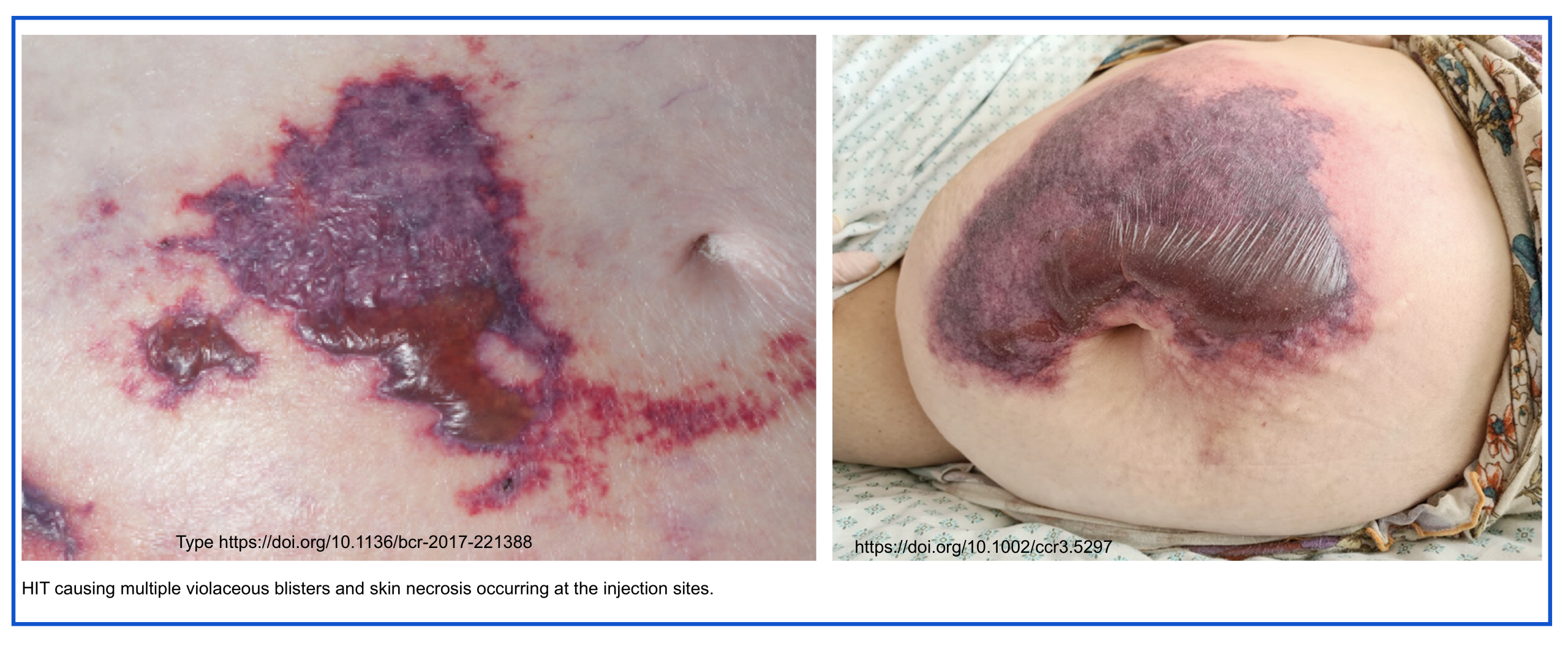

◾️Evaluate for HIT if one of the following is noted:

- Platelet count drops abruptly by >30%.

- Noted responses to heparin:

- Skin necrosis or erythema at sites of heparin injection.

- Anaphylactoid response to systemic heparin infusion.

- Venous and/or arterial thrombosis, including:

- DVT and/or PE.

- Ischemic stroke.

- Myocardial infarction.

- Limb necrosis.

◾️Diagnosis is clinical using the 4T’s score 👉 MDCalc

- Do not wait for lab confirmation to stop heparin if clinical probability is intermediate or high *.

| 4T’s Score for Heparin‑Induced Thrombocytopenia (HIT) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Thrombocytopenia (platelet count drop from baseline) | |||

| 2 points | >50% drop AND nadir ≥20,000/µL | 1 point | 30‑50% drop OR nadir 10,000‑19,000/µL |

| 0 points | <30% drop OR nadir <10,000/µL | ||

| Timing of platelet drop relative to heparin exposure | |||

| 2 points | Clear onset day 5‑10 OR ≤1 day (if heparin within past 30 days) |

1 point | Onset >10 days OR timing unclear OR day 1 with heparin 30‑100 days ago |

| 0 points | Onset <4 days with no heparin in past 100 days | ||

| Thrombosis or other sequelae | |||

| 2 points | New/progressive thrombosis, skin necrosis, anaphylactoid reaction | 1 point | Suspected thrombosis, erythematous skin lesions |

| 0 points | No thrombosis | ||

| oTher cause of thrombocytopenia | |||

| 2 points | No alternative explanation | 1 point | Possible alternative explanation |

| 0 points | Definite alternative explanation present | ||

|

Interpretation: ▪ 0‑3 points = Low probability (<1%) – HIT unlikely; no further testing. ▪ 4‑5 points = Intermediate probability (~10%) – Check PF4 antibody; consider empiric non‑heparin anticoagulant. ▪ 6‑8 points = High probability (~50%) – Treat empirically for HIT; do not wait for lab confirmation. |

|||

◾️Lab Testing (Bayesian Interpretation):

- PF4 ELISA antibody titer:

- <0.6: Negative (rules out HIT).

- 0.6‑1.5: Indeterminate; combine with 4T score.

- >1.5: Positive; post‑test probability rises with higher titer & 4T score.

- Serotonin‑release assay (SRA): Gold‑standard but slow; reserve for equivocal cases.

◾️Immediate Management:

- Stop all heparin/LMWH (place heparin allergy alert).

- Start non‑heparin anticoagulant if intermediate/high probability (do not wait for lab confirmation):

- Argatroban (DTI, titrated by aPTT).

- Bivalirudin (DTI, preferred if hepatic dysfunction).

- Fondaparinux or apixaban (oral/SC Xa inhibitors; consider if renal OK, low bleed risk).

- Avoid: Warfarin (early protein C depletion worsens thrombosis) and platelet transfusion (may provoke clotting).

◾️Severe/Autoimmune HIT:

- Features: Delayed‑onset, persistent thrombocytopenia, DIC, multi‑site thrombosis, low platelets (<20k).

- Add IVIG (1 g/kg × 2 days) for severe/refractory cases; consider plasma exchange if anticoagulation is contraindicated.

💡Key Points:

- HIT is a clinical diagnosis supported by labs; over‑testing (PF4 ELISA with low 4T score) causes false positives.

- D‑dimer is often markedly elevated (>2000 FEU) in HIT; a normal D‑dimer argues against HIT.

- Thrombosis risk peaks in the first days after platelet drop; early treatment reduces mortality/limb

2. Heparin Resistance

- Definition:

- Inability to achieve therapeutic anticoagulation (aPTT or Anti‑Xa) despite high‑dose UFH infusion (>30–35 U/kg/hr) *.

- Key Causes:

- True Resistance:

- Antithrombin (AT) deficiency *

- DIC (e.g., due to sepsis).

- Acute thrombosis (e.g., PE, DVT).

- Surgery or trauma (antithrombin III levels often nadir ~3 days postoperatively).

- Pregnancy (especially with preeclampsia).

- Exposure to devices:

- Hemodialysis.

- ECMO (AT-III deficiency is frequently seen upon ECMO initiation).

- Possibly IABP (intra-aortic balloon pump).

- Medications:

- Asparaginase therapy for malignancy.

- Unfractionated heparin itself can reduce antithrombin levels.

- Cirrhosis.

- Nephrotic syndrome.

- Low heparin concentration due to increased heparin clearance/binding *.

- Increased heparin clearance (e.g., due to splenomegaly).

- Increases in heparin binding to:

- Cells, including:

- Leukocytes (e.g., monocytes).

- Thrombocytosis (e.g., platelet count >300,000/uL).

- Acute-phase proteins, including:

- Fibrinogen.

- Factor VIII.

- von Willebrand factor (vWF).

- Extracorporeal circuit components.

- Andexanet alfa.

- Cells, including:

- Antithrombin (AT) deficiency *

- Pseudo‑Resistance: Elevated factor VIII/fibrinogen (from inflammation) artifactually lowers PTT while Anti‑Xa is therapeutic *.

- True Resistance:

- Immediate Workup:

- Draw concurrent Anti‑Xa and aPTT (discordance suggests pseudo‑resistance).

- Check Antithrombin (AT) activity.

- Consider fibrinogen & factor VIII if pseudo‑resistance is suspected.

- Diagnosis:

- The key to diagnosis is measuring the anti-Xa activity, a more accurate measurement of heparin’s activity (which is not affected by factor VIII and/or fibrinogen).

- Factor VIII and fibrinogen levels may also be measured to provide some indirect support to the diagnosis.

- Management:

- If both Anti‑Xa & aPTT are low: Increase heparin dose (up to 40–70 U/kg/hr).

- If AT deficiency is severe (<40%): Switch to a direct thrombin inhibitor (e.g., argatroban) — preferred over costly, evidence‑poor AT concentrate.

- If pseudo‑resistance (low aPTT, therapeutic Anti‑Xa): Titrate heparin by Anti‑Xa level only; ignore aPTT to avoid overdose.

Bottom Line: Use Anti‑Xa monitoring when available. For true resistance with low AT, switch to argatroban rather than chasing doses or giving AT concentrate.

B. Systems Support & Care Coordination

The ED must act as a bridge, not a cliff. This requires intentional system design.

- Structured Patient Education

- Education must be initiated in the ED, delivered in a clear, concise, and multimodal fashion to address health literacy barriers.

- Core Content (“The Four W’s”):

- WHY: Explain the specific reason for anticoagulation (e.g., “This medication is a blood thinner to prevent strokes caused by your irregular heart rhythm”).

- WHAT & WHEN: State the drug’s brand and generic name, exact dose, and precise timing (e.g., “You will take rivaroxaban, 20 mg, one pill once daily with your evening meal”). Emphasize adherence.

- WARNINGS:

- Bleeding Signs: Instruct patients to seek immediate care for head injury, uncontrollable bleeding, red/black stools, coughing/vomiting blood, severe headache, or weakness.

- Thrombosis Signs: Reinforce symptoms of stroke (FAST: Face, Arm, Speech, Time) or PE (sudden shortness of breath, chest pain).

- INTERACTIONS & PRECAUTIONS: Review avoidance of NSAIDs (e.g., ibuprofen), caution with alcohol, and the need to inform all other healthcare providers (including dentists) about their anticoagulant use.

- Delivery Method: Combine verbal teaching (teach-back method), written materials (take-home instructions in plain language), and, if available, video resources or links to reputable websites (e.g., the American Heart Association).

- Core Content (“The Four W’s”):

- Education must be initiated in the ED, delivered in a clear, concise, and multimodal fashion to address health literacy barriers.

- Medication Access

- The single greatest point of failure is the patient leaving without medication. Systems must ensure the first dose is administered in the ED and that a full supply is immediately accessible. This can be achieved via:

- ED pharmacy dispensation of a “starter pack” (3-7 day supply).

- A verified e-prescription sent to a 24-hour pharmacy with a confirmed patient pickup plan.

- Use of manufacturer patient-assistance programs or sample kits where appropriate and compliant.

- The single greatest point of failure is the patient leaving without medication. Systems must ensure the first dose is administered in the ED and that a full supply is immediately accessible. This can be achieved via:

- Information Transmission

- A direct handoff is ideal. The ED must communicate the initiation to the patient’s Primary Care Provider (PCP) and/or managing cardiologist/hematologist via a structured mechanism (e.g., direct phone call, secure message in the electronic health record, or faxed summary) on the day of discharge.

- This communication should include the indication, agent/dose, renal function, bleeding risk assessment, and the planned follow-up date.

- Anticoagulation Management Service (AMS) Referral

- Where available, an immediate referral to a dedicated AMS or pharmacist-led clinic provides expert longitudinal management and is a best practice.

- Mandatory Short-Term Follow-Up

- A specific, scheduled follow-up appointment within 3 to 7 days is non-negotiable for ED-initiated patients. This appointment serves multiple critical functions:

- Reinforcement: Re-educate and assess understanding.

- Safety Check: Review for early signs of bleeding or adverse effects, re-check renal function if indicated, and assess adherence.

- Therapy Adjustment: Confirm appropriate long-term agent and dose based on more comprehensive outpatient evaluation.

- Continuity: Formally transfer care from the episodic ED setting to the longitudinal outpatient provider.

- The Follow-Up “Safety Net”: Patients must be given explicit, written instructions on what to do if they cannot secure or attend their follow-up appointment (e.g., “Call this clinic number or return to the ED for guidance”). This closes the loop and prevents patients from falling out of care.

- A specific, scheduled follow-up appointment within 3 to 7 days is non-negotiable for ED-initiated patients. This appointment serves multiple critical functions:

Special Populations and Complex Scenarios

While the general pathway for ED anticoagulation initiation provides a robust framework, specific patient subgroups present unique challenges that require tailored decision-making. A “one-size-fits-all” approach risks either under-treatment or harm. This section addresses key considerations for special populations and complex clinical scenarios frequently encountered in the ED.

Elderly Patient and Fall Risk

Advanced age is a component of both stroke (CHA₂DS₂-VASc) and bleeding (HAS-BLED) risk scores, creating a perceived therapeutic dilemma. However, evidence strongly supports anticoagulation in the elderly with AF, as their higher baseline stroke risk means the net clinical benefit remains favorable.

- Key Principle

- A history of falls alone is not an absolute contraindication to anticoagulation. The risk of traumatic intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) must be weighed against the significant daily risk of cardioembolic stroke.

- ED Assessment & Mitigation

- Quantify the Risk

- Distinguish between a single, accidental fall and recurrent, mechanical falls, indicating syncope, gait instability, or neurodegenerative disease.

- Focus on Modifiable Factors

- Screen for orthostatic hypotension, review medications contributing to fall risk (e.g., sedatives, antihypertensives), and initiate referrals for gait assessment and home safety evaluations.

- Agent Consideration

- While all anticoagulants carry bleeding risk, some data suggest apixaban may have a lower risk of ICH compared to warfarin, which may be a consideration in this population. Dose adjustment for age, weight, and renal function is paramount.

- Quantify the Risk

- Disposition

- For a patient with recurrent, unexplained falls, initiation may be safely deferred for 24-48 hours in an ED Observation Unit or inpatient setting to allow for urgent outpatient geriatric or cardiology evaluation to address the root cause, while stroke risk is briefly managed with bridging strategies if deemed high risk.

Renal Impairment

Renal function dictates DOAC eligibility, dosing, and safety.

- ED Action Algorithm:

- Obtain a Serum Creatinine & Estimate GFR (eGFR) on all patients before initiation.

- eGFR >30 mL/min

- All DOACs are generally permissible with appropriate dose adjustments (refer to specific agent guidelines).

- Apixaban or rivaroxaban may be preferred in moderate impairment (CrCl 30-50 mL/min) due to their studied dosing schemes.

- eGFR 15-30 mL/min (Severe Impairment)

- Apixaban is the only DOAC with specific dosing guidance and outcome data in this range. Use with caution and at a reduced dose.

- Warfarin remains an alternative, but requires bridging and complex outpatient management.

- eGFR <15 mL/min or on Dialysis

- DOACs are contraindicated.

- Initiation of anticoagulation for AF in this population is highly complex and requires shared decision-making with nephrology.

- ED initiation is generally not appropriate; consultation and admission for coordinated planning are advised.

| Anticoagulant Class & Agent | Primary Renal Excretion | CrCl ≥50 mL/min (Normal-Mild) |

CrCl 30-49 mL/min (Moderate) |

CrCl 15-29 mL/min (Severe) |

CrCl <15 mL/min / Dialysis (ESRD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin K Antagonists (VKAs) | |||||

| Warfarin | Minimal (hepatic) (Inactive metabolites renally excreted) |

Standard Risk Standard dosing & monitoring (INR 2.0-3.0). Bleeding risk dependent on INR control. |

↑ Risk More labile INR. Increased bleeding risk due to comorbidities. Monitor closely. |

↑↑ Risk High bleeding risk. Use lower initial doses. Frequent INR monitoring required. |

↑↑ Risk (Variable) Can be used but challenging. Altered protein binding/vitamin K status. Not for ED initiation. |

| Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs) | |||||

| Apixaban | ~27% |

Standard Risk 5 mg BID (2.5 mg BID if 2 of: age≥80, wt≤60kg, SCr≥1.5). |

↑ Risk 2.5 mg BID (recommended). Preferred DOAC in this range. |

↑ Risk 2.5 mg BID (only DOAC with specific dosing). |

↑↑ Risk Generally contraindicated. Limited data. 2.5 mg BID may be used off-label in HD with specialist consultation. |

| Rivaroxaban | ~36% (33% unchanged) |

Standard Risk 20 mg daily with food (15 mg if CrCl 50-60). |

↑ Risk 15 mg daily with food. |

↑↑ Risk Avoid / Not recommended. |

↑↑ Risk Contraindicated. |

| Dabigatran | ~80-85% |

Standard Risk 150 mg BID (110-150 mg based on bleeding risk). |

↑ Risk 75 mg BID (if CrCl 30-50 & high bleed risk). Avoid if possible. |

↑↑ Risk Contraindicated. |

↑↑ Risk Contraindicated. |

| Edoxaban | ~50% |

Standard Risk 60 mg daily. |

↑ Risk 30 mg daily. |

↑↑ Risk Avoid / Not recommended. |

↑↑ Risk Contraindicated. |

| Parenteral Anticoagulants | |||||

| Enoxaparin (LMWH) | Renal (significant) |

Standard Risk Standard prophylactic or therapeutic dosing. |

↑ Risk Monitor anti-Xa levels for therapeutic dosing. Consider dose reduction. |

↑↑ Risk Avoid for therapeutic use. Prophylactic dose only with extreme caution. Anti-Xa monitoring mandatory. |

↑↑↑ Accumulation Risk Contraindicated for therapeutic use. Minimal prophylactic data. Use unfractionated heparin (UFH) instead. |

| Unfractionated Heparin (UFH) | Minimal (hepatic/RES) |

Standard Risk Standard weight-based dosing, monitor aPTT. |

Standard Risk No dose adjustment. Standard monitoring. |

Standard Risk Drug of choice for severe renal impairment. No dose adjustment. |

Standard Risk Drug of choice for ESRD. No dose adjustment. Monitor aPTT. |

| Fondaparinux | ~77% (unchanged) |

Standard Risk Standard dosing (2.5 mg prophylaxis, 7.5 mg treatment*). |

↑ Risk Use with caution. Contraindicated if CrCl <30 for prophylaxis. |

↑↑ Risk Contraindicated for prophylaxis. Avoid for treatment. |

↑↑↑ Risk Contraindicated. |

| Argatroban (Direct Thrombin Inhibitor) | Hepatic | No renal dose adjustment required. Preferred parenteral agent for HIT with any degree of renal failure. Dose adjustment needed for hepatic impairment. | |||

|

Key & Abbreviations: CrCl = Creatinine Clearance (Cockcroft-Gault); ESRD = End-Stage Renal Disease; BID = Twice Daily; INR = International Normalized Ratio; aPTT = Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time; LMWH = Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin; UFH = Unfractionated Heparin; HIT = Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia. Risk Classification: Low/Standard Risk = Generally safe for ED initiation with standard precautions. Moderate/Increased Risk = Use with caution, closer monitoring, consider specialist consultation. High Risk = Generally avoid ED initiation; requires specialist consultation and often admission. * Fondaparinux treatment dose is weight-based: <50 kg = 5 mg; 50-100 kg = 7.5 mg; >100 kg = 10 mg. |

|||||

💡Pearl

- Clinical Decision Guide for Renal Disease

- ⚠️Most Renal-Dependent: Dabigatran > Enoxaparin > Edoxaban > Fondaparinux

- ✅Safest in Renal Failure: UFH, Argatroban, Warfarin (no dose adjustment, but other risks).

- ☑️Preferred DOAC for Moderate Renal Impairment: Apixaban (least renal clearance).

- 🧐Intermediate & Requiring Caution: Bivalirudin (requires dose reduction in severe renal failure, CrCl <30 mL/min).

Hepatic Impairment and Liver Disease

The liver synthesizes both clotting factors and proteins involved in anticoagulant metabolism, creating a dual risk of thrombosis and bleeding. Assessment is more nuanced than renal function.

- Risk Stratification: Use the Child-Pugh classification (based on bilirubin, albumin, INR, ascites, encephalopathy) for cirrhotic patients.

- Child-Pugh A (Mild)

- DOACs (particularly apixaban or rivaroxaban) may be considered with caution and often at reduced dose, though data are limited.

- Consultation with hepatology or hematology is strongly advised before ED initiation.

- Child-Pugh B (Moderate)

- DOACs are generally not recommended. The bleeding risk is significantly elevated, and metabolism is unpredictable.

- For acute VTE or high-risk AF, admission for consultation and consideration of low-dose LMWH (e.g., enoxaparin 0.5 mg/kg twice daily) is typically required.

- Child-Pugh C (Severe)

- Anticoagulation is contraindicated in most circumstances due to profound coagulopathy and high bleeding risk.

- ED initiation must not occur. These patients require urgent hepatology consultation, and management of portal hypertension/thrombosis is highly specialized.

- Child-Pugh A (Mild)

- Non-Cirrhotic Liver Disease

- For patients with acute hepatitis or significant cholestasis, DOACs are also poorly studied. A conservative approach with LMWH and specialist consultation is prudent.

🏥ED Action: For any patient with known or suspected significant liver disease (evidenced by elevated INR not on warfarin, hypoalbuminemia, jaundice, or ascites), ED initiation of a DOAC is strongly discouraged.

- 🏨The pathway should involve consultation and, typically, inpatient admission for multidisciplinary evaluation.

| Anticoagulant Class & Agent | Hepatic Metabolism | Child-Pugh A (Mild Impairment) |

Child-Pugh B (Moderate Impairment) |

Child-Pugh C (Severe Impairment) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin K Antagonists (VKAs) | ||||

| Warfarin | Extensive (CYP2C9, 3A4, 1A2) Vitamin K dependent factor synthesis in liver |

↑ Risk (Variable) Can be used but requires intensive INR monitoring. INR may be labile due to variable factor synthesis, malnutrition, or ascites. |

↑↑ Risk Use with extreme caution. Frequent INR checks (q2-3d initially). High bleeding risk from coagulopathy & portal hypertension. |

↑↑↑ Risk Generally contraindicated for chronic therapy. Unpredictable response. If absolutely necessary (e.g., mechanical valve), manage in inpatient setting with hepatology/hematology. |

| Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs) | ||||

| Apixaban | ~75% (CYP3A4) 25% renal excretion |

↑ Risk (Caution) May be used with caution. Limited data suggest no significant exposure change in Child-Pugh A. Consider reduced dose (2.5 mg BID). |

↑↑ Risk (Not Recommended) Avoid or use with extreme caution. Exposure increased by ~30%. Increased bleeding risk. If essential, use 2.5 mg BID with specialist consultation. |

↑↑↑ Risk Contraindicated. Exposure increased by ~70%. No clinical data. High bleeding risk from baseline coagulopathy. |

| Rivaroxaban | ~65% (CYP3A4, 2J2) 33% renal excretion unchanged |

↑ Risk (Caution) Use with caution. Exposure increased ~1.2x. Avoid in hepatic disease associated with coagulopathy. |

↑↑ Risk Contraindicated per most labels. Exposure increased ~1.6x. Avoid. |

↑↑↑ Risk Contraindicated. Exposure increased ~2.3x. Absolute avoidance. |

| Dabigatran | Minimal (conjugation) 80-85% renal excretion |

Standard Risk Can be used. Not extensively metabolized by CYP system. |

↑ Risk (Avoid) Avoid. Exposure increased ~2.5x. Significant bleeding risk. |

↑↑↑ Risk Contraindicated. No data. High bleeding risk. |

| Edoxaban | Minimal (hydrolysis, CYP3A4) 50% renal excretion |

Standard Risk Can be used. No dose adjustment needed in mild impairment. |

↑↑ Risk Contraindicated per label. Avoid. |

↑↑↑ Risk Contraindicated. |

| Parenteral Anticoagulants | ||||

| Enoxaparin (LMWH) | Minimal (renal clearance) Hepatic desulfation minor pathway |

Standard Risk Standard dosing acceptable. Monitor for signs of bleeding. |

↑↑ Risk Use with extreme caution. Reduced antithrombin levels may diminish effect. Increased bleeding risk from coagulopathy. Consider anti-Xa monitoring. |

↑↑↑ Risk Generally avoid. High bleeding risk. If absolutely necessary, use at reduced dose with anti-Xa monitoring and specialist consultation. |

| Unfractionated Heparin (UFH) | Minimal (hepatic/RES) Renal excretion minimal |

Standard Risk Drug of choice for many hepatic patients. No dose adjustment. Monitor aPTT. |

↑ Risk (Preferred) Preferred parenteral agent in moderate-severe liver disease. Short half-life, reversible. Monitor aPTT closely. |

↑↑ Risk (Cautious Use) Preferred agent if anticoagulation essential. Use with caution (baseline aPTT may be elevated). Frequent monitoring. Half-life may be prolonged. |

| Fondaparinux | Minimal 77% renal excretion unchanged |

Standard Risk No dose adjustment needed. |

Standard Risk No dose adjustment needed. However, avoid if concomitant renal impairment. |

↑ Risk Use with caution. Limited data. Bleeding risk elevated due to underlying coagulopathy. |

| Argatroban (Direct Thrombin Inhibitor) | Extensive (hepatic, CYP3A4/5) Primary biliary excretion |

Standard Risk Standard dosing. Monitor aPTT. |

↑↑ Risk Reduce dose by 75%. Required due to decreased clearance. Monitor aPTT closely. |

↑↑↑ Risk Generally avoided. If essential, drastic dose reduction with continuous monitoring. Avoid in severe impairment. |

| Bivalirudin | Minimal (proteolytic cleavage) 20% renal excretion |

Standard Risk Standard dosing. Monitor aPTT/ACT. |

Standard Risk No dose adjustment needed. Preferred DTI in hepatic impairment over argatroban. |

↑ Risk Can be used with caution. Dose reduction may be needed. Monitor closely. |

|

Key & Clinical Guidance: Child-Pugh A: Score 5-6; Child-Pugh B: 7-9; Child-Pugh C: 10-15. INR in score reflects underlying liver disease, not anticoagulation. General Principles: 1) Avoid all anticoagulants in acute liver failure. 2) Baseline coagulopathy (elevated INR, low platelets) significantly increases bleeding risk regardless of agent. 3) Portal hypertension and varices are major bleeding risk factors. 4) UFH is often the safest initial choice for hospitalized patients with significant liver disease due to short half-life and reversibility. ED Action: For Child-Pugh B/C, avoid ED initiation of DOACs/VKAs. Consultation with hepatology/hematology and inpatient management are strongly recommended. For Child-Pugh A, use caution and consider UFH/LMWH if therapy must start in ED. |

||||

💡Bottom Line

- ✅In significant liver disease (Child-Pugh B/C or coagulopathy), Unfractionated Heparin (UFH) is the safest and most controllable option.

- ⚠️All DOACs and warfarin carry high, often prohibitive risk.

- 👉The prescribing rule: Liver failure → Think Heparin (UFH/LMWH with monitoring).

Cancer-Associated Thrombosis (CAT)

Patients with active cancer have a 5-7 times higher risk of VTE and often require anticoagulation. The ED is a common point of diagnosis.

- First-Line Therapy

- Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin (LMWH), such as enoxaparin, has been the long-standing standard for CAT due to superior efficacy over warfarin.

- DOACs in CAT

- Select DOACs (edoxaban, rivaroxaban, apixaban) are now approved for CAT. However, they require careful patient selection due to increased bleeding risk, particularly in patients with:

- Gastrointestinal (especially upper GI) cancers.

- Genitourinary cancers are at risk of mucosal bleeding.

- Thrombocytopenia (platelets <50,000/μL).

- Select DOACs (edoxaban, rivaroxaban, apixaban) are now approved for CAT. However, they require careful patient selection due to increased bleeding risk, particularly in patients with:

- 🏥ED Approach

- For stable CAT patients without high bleeding risk features or severe thrombocytopenia, ED initiation of a DOAC (following renal/hepatic dosing) is reasonable and aligns with modern guidelines.

- For patients with GI malignancies, severe thrombocytopenia, or other high-risk features, consultation with oncology or hematology and consideration of LMWH (which can be taught for self-injection) is prudent. Admission may be required for complex cases.

Concomitant Antiplatelet Therapy

Initiating anticoagulation in a patient on antiplatelet therapy is one of the most common and high-risk decisions in the ED. The combination multiplies bleeding risk, requiring a clear, indication-driven strategy. The guiding principle is that every additional antithrombotic agent must have a distinct and compelling indication.

◾️Risk Stratification and General Rule

- The bleeding risk escalates with each agent:

- Anticoagulant alone: Baseline risk.

- Anticoagulant + single antiplatelet (SAPT): ~1.5x increased major bleeding risk.

- Anticoagulant + dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT): ~2-3x increased major bleeding risk (“triple therapy”).

🏥The default ED action for a stable patient starting anticoagulation for stroke prevention (AF) or VTE treatment is to discontinue non-essential antiplatelets.

- The anticoagulant provides superior efficacy for its indication.

📊Reference: Antiplatelet Agent Profiles

- To make informed decisions, clinicians must understand the pharmacology of the antiplatelet agents their patients are taking. The following table summarizes key characteristics.

| Class & Generic Name | Route | Onset | Half-Life | Mechanism | Key Indications | Major Contraindications | Reversal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORAL AGENTS | Oral Antiplatelets | ||||||

| Aspirin (Acetylsalicylic Acid) | PO | 15-30 min | 2-3h (dose-dependent) | Irreversible COX-1 inhibitor Blocks TXA₂ production |

• ACS & secondary prevention • Ischemic stroke/TIA prevention • Primary prevention (select high-risk) • PCI (with P2Y₁₂ inhibitor) |

• Active bleeding/peptic ulcer • Severe hepatic failure • Asthma with nasal polyps • Children with viral illness |

Platelet transfusion DDAVP may help |

| Clopidogrel | PO | 2h (peak 6h) | 6h (active metabolite) | Irreversible P2Y₁₂ inhibitor Prodrug requiring CYP activation |

• ACS (with aspirin) • Post-PCI/stenting • Secondary stroke prevention • PAD with symptomatic limb ischemia |

• Active bleeding • Severe liver disease • CYP2C19 poor metabolizers |

Platelet transfusion (wait 6h after dose) |

| Prasugrel | PO | 30 min (peak 4h) | 7h (active metabolite) | Irreversible P2Y₁₂ inhibitor More consistent activation |

• ACS with planned PCI • Post-stenting (DES) • High thrombotic risk |

• Prior TIA/stroke • Age ≥75 years • Weight <60 kg • Active bleeding |

Platelet transfusion (wait 7h after dose) |

| Ticagrelor | PO | 30 min (peak 2h) | 7-9h | Reversible P2Y₁₂ inhibitor Direct-acting, non-prodrug |

• ACS (with aspirin) • Post-PCI/stenting • High-risk CAD • Post-MI without PCI |

• Active bleeding • History of intracranial hemorrhage • Severe hepatic impairment • Concurrent strong CYP3A4 inhibitors |

Platelet transfusion Short half-life allows discontinuation |

| Cilostazol | PO | 2-4h | 11-13h | PDE3 inhibitor Vasodilator + antiplatelet |

• Intermittent claudication (PAD) • Secondary stroke prevention (Asia) • In-stent restenosis prevention |

• Heart failure (any class) • Active bleeding • Severe hepatic/renal impairment |

Discontinuation Supportive care |

| Dipyridamole | PO | 30-60 min | 10-12h | PDE inhibitor + Adenosine reuptake inhibitor | • Stroke/TIA prevention • With aspirin (Aggrenox) • Post-CABG graft patency • Myocardial perfusion imaging |

• Active bleeding • Severe CAD (can cause angina) • Hypotension • Severe hepatic impairment |

Discontinuation Supportive care |

| Vorapaxar | PO | 1-2h | 5-13 days | PAR-1 thrombin receptor antagonist | • Secondary prevention in stable atherosclerosis • Post-MI • PAD (with aspirin/clopidogrel) |

• History of stroke/TIA/ICH • Active bleeding • Not for ACS patients |

Platelet transfusion Very long half-life |

| INTRAVENOUS AGENTS | IV Antiplatelets (Acute Care) | ||||||

| Abciximab | IV | Immediate | 10-30 min (biological) | GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor Monoclonal antibody fragment |

• PCI (high-risk) • ACS with planned PCI • Thrombotic complications during PCI |

• Active bleeding • Recent surgery/trauma • History of stroke (within 2y) • Severe thrombocytopenia |

Platelet transfusion Discontinue infusion |

| Eptifibatide | IV | Immediate | 2.5h | GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor Cyclic heptapeptide |

• ACS (with/without PCI) • NSTEMI • PCI (especially with clopidogrel loading) |

• Active bleeding • Severe renal impairment (CrCl <30) • Recent stroke/surgery • Thrombocytopenia |

Platelet transfusion Discontinue infusion |

| Tirofiban | IV | Immediate | 2h | GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor Non-peptide tyrosine derivative |

• ACS (NSTEMI/UA) • With planned PCI • Bridge to cardiac surgery |

• Active bleeding • Severe renal impairment • Recent stroke/surgery • Thrombocytopenia |

Platelet transfusion Discontinue infusion |

| Cangrelor | IV | Immediate | 3-6 min | Reversible P2Y₁₂ inhibitor Direct-acting, very rapid |

• PCI (without preloading) • Bridge therapy for surgery • ACS with urgent PCI • When oral P2Y₁₂ not possible |

• Active bleeding • Severe hepatic impairment • Not for use with other IV antiplatelets |

Discontinue infusion Very short half-life |

Routes: PO = Oral, IV = Intravenous

Mechanisms: COX-1 = Cyclooxygenase-1, P2Y₁₂ = ADP receptor, GP IIb/IIIa = Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa, PDE = Phosphodiesterase, PAR-1 = Protease-activated receptor-1