19 December 2025 by Shahriar Lahouti.

CONTENTS

- Preface

- Terminology

- Risk Factors

- Venous Anatomy

- Clinical Presentation

- Differential Diagnosis of DVT

- Diagnostic Evaluation

- Pretest Probability Estimation

- D-dimer

- Radiologic Evaluation

- Diagnostic Approach

- Management Principles

- Stepwise guide to DVT treatment initiation

- Specific Situation

- Media

- Going further

- References

Preface

Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) is a common and potentially life-threatening vascular emergency that every clinician will encounter. This silent threat, often presenting with subtle or classic signs of unilateral leg pain and swelling, carries the significant risk of pulmonary embolism and long-term morbidity.

This comprehensive guide synthesizes the latest evidence and guidelines into a clear, stepwise approach for the practicing physician. From bedside assessment using validated tools like the Wells’ criteria and D-dimer, through point-of-care ultrasound protocols, to the nuanced decisions of anticoagulation and disposition, we provide the essential knowledge for accurate diagnosis and effective management. Our focus is on practical application—equipping readers with the confidence to safely rule out DVT, initiate timely treatment, and prevent complications in both typical and complex presentations.

Terminology

- Provoked DVT

- A provoked DVT is precipitated by a known event (eg, surgery, hospital admission, estrogen). It is now also referred to as DVT associated with an

identifiable risk factor(s). - Risk factors can be transient or persistent. Transient risk factors are further categorized as “major” or “minor” according to the magnitude of venous thromboembolism (VTE) risk conferred.

- A provoked DVT is precipitated by a known event (eg, surgery, hospital admission, estrogen). It is now also referred to as DVT associated with an

- Unprovoked DVT

- An unprovoked DVT occurs in the absence of identifiable risk factors.

- Superficial thrombophlebitis or superficial vein thrombosis (SVT). More on this here.

- It results from thrombus formation in a superficial vein with associated inflammation of the vessel wall *.

Risk Factors

A risk factor (table below) can be identified in >80% of patients with venous thromboembolism (VTE). Furthermore, more than one factor is often present in a given patient.

| Risk Category | Risk Factors |

|---|---|

| High Risk (OR > 10) |

• Orthopedic: Hip/knee fracture, or replacement.1 • Surgery/Trauma: Major general surgery, major trauma, spinal cord injury with paralysis.1 • Prior VTE (DVT/PE).1 • Cardiac disease: CHF/AF hospitalization within 3 months, recent MI.2 • Homozygous Factor V Leiden mutation.4 |

| Moderate Risk (OR 2–10) |

• Age >80 years old.1 • Central venous catheter/pacemaker leads.7 • Arthroscopic knee surgery.1 • Paralytic stroke.3 OB&Gyn: • Estrogen contraceptives.5 • HRT (estrogen).2 • Postpartum (esp. C-section).5 • IVF.2 • Active cancer (lung, pancreas, gastric, kidney, prostate, brain, hematologic).1, 7 • Congestive heart failure.2 • Respiratory failure (e.g., COPD).3 • Familial protein C/S/antithrombin deficiency.3 • Heterozygous Factor V Leiden mutation.4 • Inflammatory bowel disease.3 • Autoimmune disease.3 • HIT (untreated).1 • Infection (pneumonia, UTI, HIV).7 • Superficial vein thrombosis.2 • Erythropoietin use.7 |

| Low Risk (OR < 2) |

• Pregnancy.5 • Long travel (>6 h).2 • Bed rest >3 days.1 • Varicose veins.3 • Obesity (BMI >35).1 • Smoking.2 • DM.7 • HTN.7 • Older age (<80).1 • Laparoscopic surgery.7 |

References (click to expand)

- Heit JA, et al. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(6):809–815.

- Anderson FA, Spencer FA. Circulation. 2003;107:I-9–I-16.

- Kyrle PA, Eichinger S. Lancet. 2005;365:1163–1174.

- Rosendaal FR. Lancet. 1999;353:1167–1173.

- Lijfering WM, et al. Thromb Haemost. 2009;101:498–503.

- Prandoni P, et al. Haematologica. 2007;92:199–205.

- Kearon C, et al. CHEST Guideline. Chest. 2021;160:e545–e608.

- Konstantinides SV, et al. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:543–603.

- Raskob GE, et al. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:2363–2371.

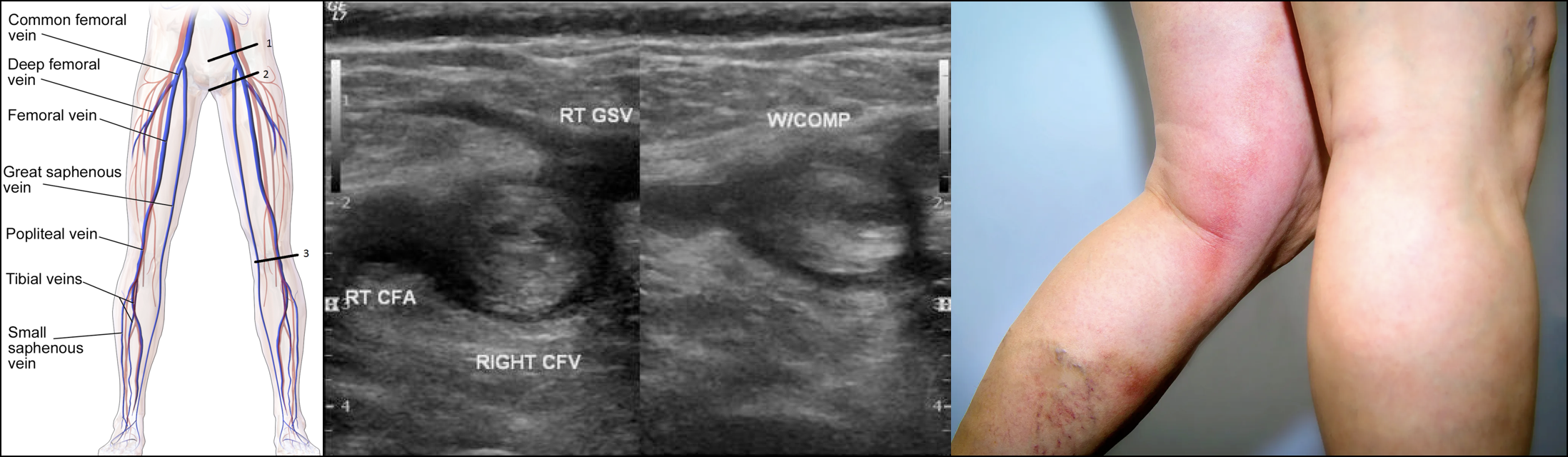

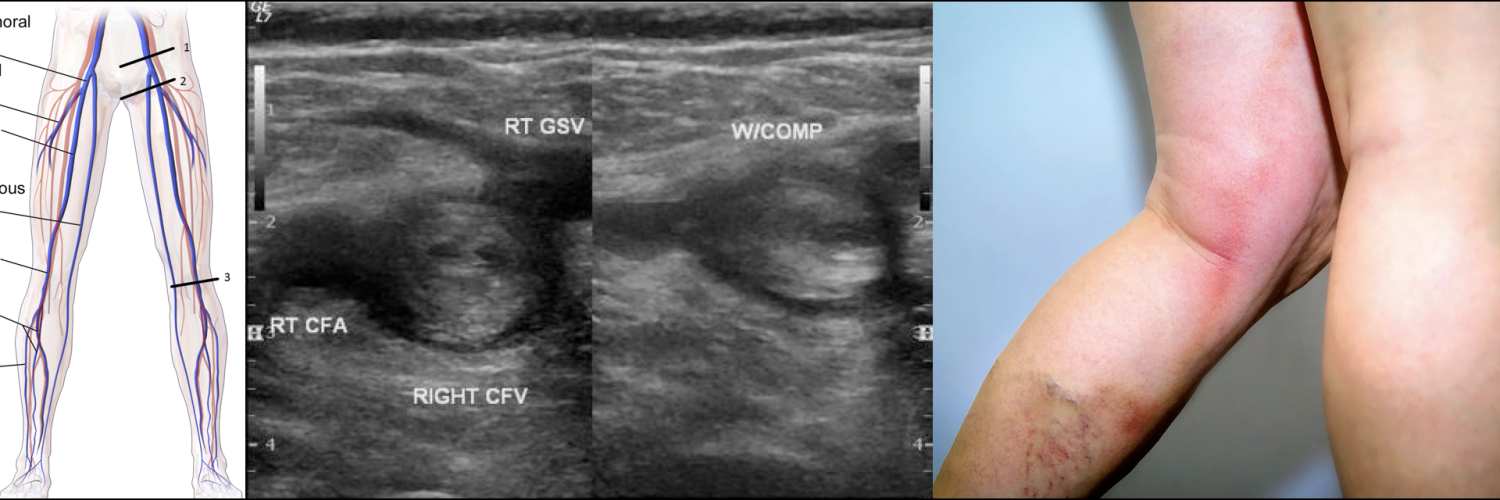

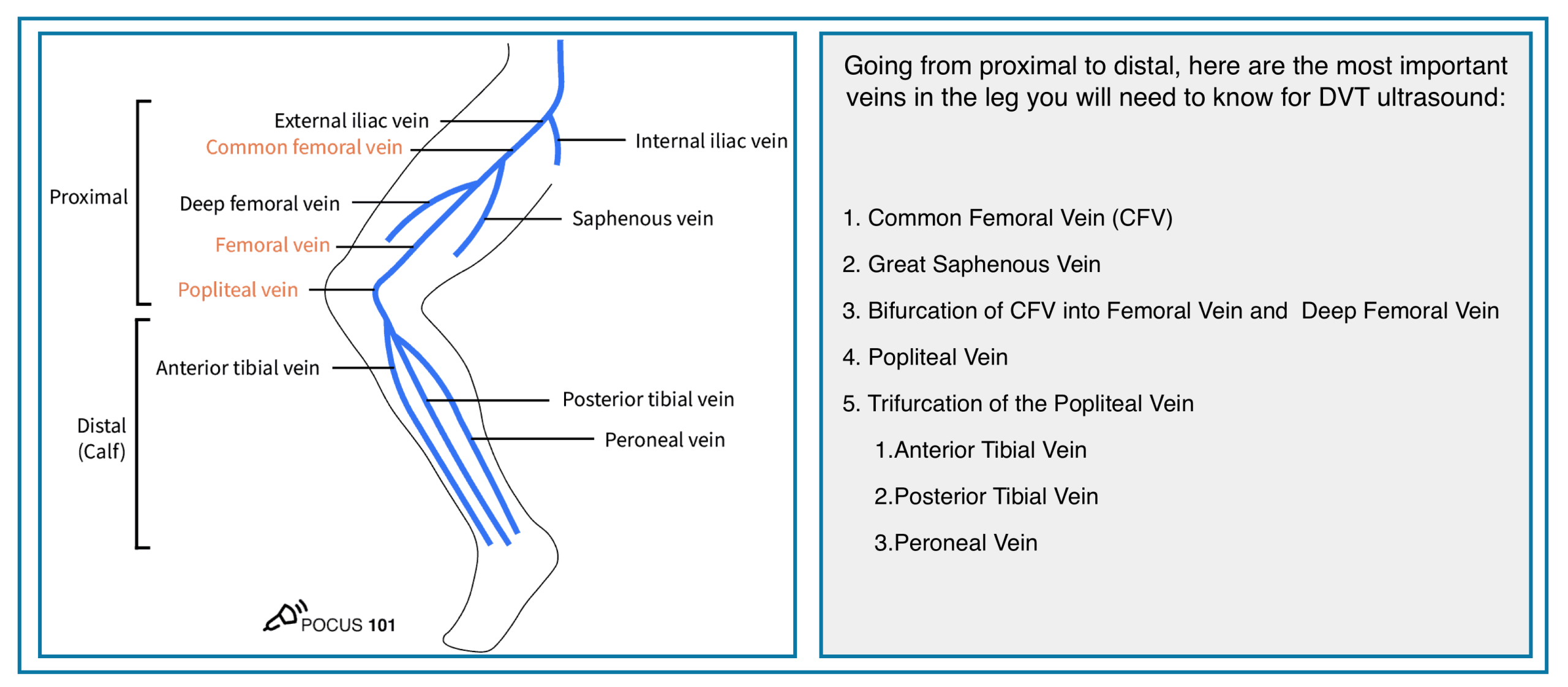

Venous Anatomy

◾️Knowledge of the venous anatomy is crucial for the following reasons:

- For the performance and interpretation of the ultrasound of the leg veins

- The anatomic location of a DVT also influences prognosis because proximal DVTs are less likely to lyse spontaneously, more likely to embolize, and are associated with a greater risk of long-term complications such as post-thrombotic syndrome.

- The probability that a DVT will cause a PE depends significantly on the location of the thrombus.

◾️The anatomy of the extremities’ veins is shown in the figures below.

- Deep veins of the lower extremity

- The deep venous system includes the anterior tibial, posterior tibial, and peroneal veins, collectively called the calf veins *.

- Venous thrombi isolated to the calf veins are referred to as distal DVT.

- The calf veins join together at the knee to form the popliteal vein, which extends proximally and becomes the femoral vein at the adductor canal *.

- Venous thrombi in the popliteal or more proximal veins are referred to as proximal DVT.

- The femoral vein (previously known as the superficial femoral vein) is joined by the deep femoral vein and then the greater saphenous vein to form the common femoral vein, which subsequently becomes the external iliac vein at the inguinal ligament *.

- Venous thrombi in the proximal femoral and iliac veins are known as iliofemoral DVT.

- The deep venous system includes the anterior tibial, posterior tibial, and peroneal veins, collectively called the calf veins *.

- Superficial veins of the lower extremity

- In the lower extremity, the superficial venous system consists primarily of the greater and short saphenous veins and perforating veins *.

- Distal greater saphenous vein thrombi are often referred to as superficial thrombosis, but greater saphenous clots near the connection with the femoral vein should be referred to as DVT.

- In the lower extremity, the superficial venous system consists primarily of the greater and short saphenous veins and perforating veins *.

Deep Veins of the Extremities

Proximal (Above-Knee)

- • Common Femoral Vein (CFV)

- • Femoral Vein (FV)

- • Deep Femoral Vein (Profunda Femoris)

- • Popliteal Vein

Distal (Calf)

- • Anterior Tibial Veins (paired)

- • Posterior Tibial Veins (paired)

- • Peroneal (Fibular) Veins (paired)

- • Gastrocnemius Veins

- • Soleal Sinuses

Arm & Forearm

- • Brachial Veins (paired)

- • Ulnar Veins (paired)

- • Radial Veins (paired)

- • Interosseous Veins

Shoulder Region

- • Axillary Vein

- • Subclavian Vein

• Upper extremity DVT often catheter-related or thoracic outlet syndrome

• All deep vein thromboses require anticoagulation unless contraindicated

Superficial Veins of the Extremities

Major Trunks

- • Great Saphenous Vein (GSV)

- • Small Saphenous Vein (SSV)

- • Anterior Accessory Saphenous Vein

- • Intersaphenous Vein (Giacomini)

Tributaries & Networks

- • Dorsal Venous Arch (foot)

- • Dorsal Metatarsal Veins

- • Medial Marginal Vein

- • Lateral Marginal Vein

- • Posterior Arch Vein (Leonardo)

Arm & Forearm

- • Cephalic Vein

- • Basilic Vein

- • Median Cubital Vein

- • Accessory Cephalic Vein

- • Median Antebrachial Vein

Hand & Dorsum

- • Dorsal Venous Network

- • Dorsal Metacarpal Veins

- • Digital Veins

• Superficial thrombophlebitis is treated differently from DVT

• Great Saphenous Vein often harvested for CABG surgery

• Varicose veins typically involve superficial venous system

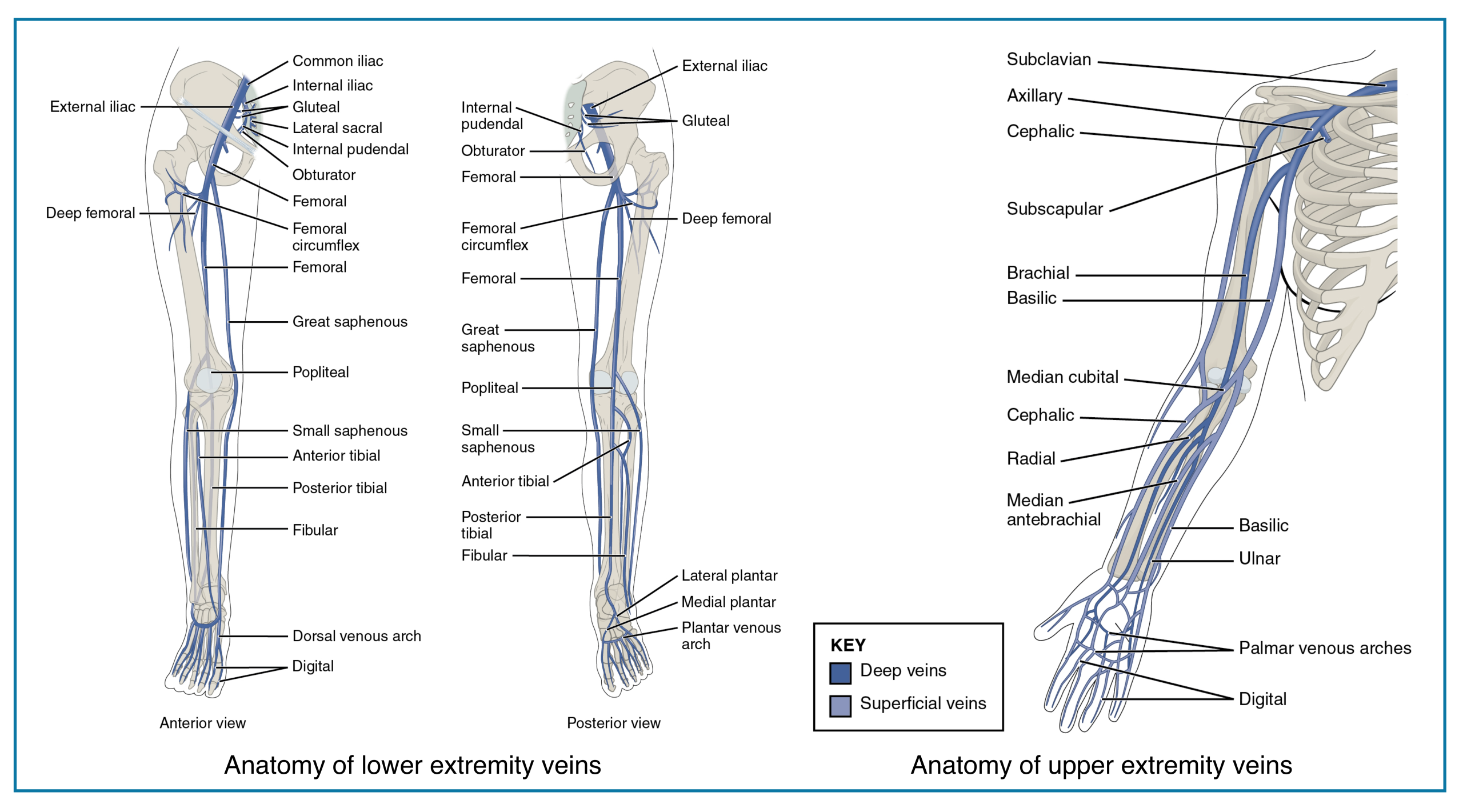

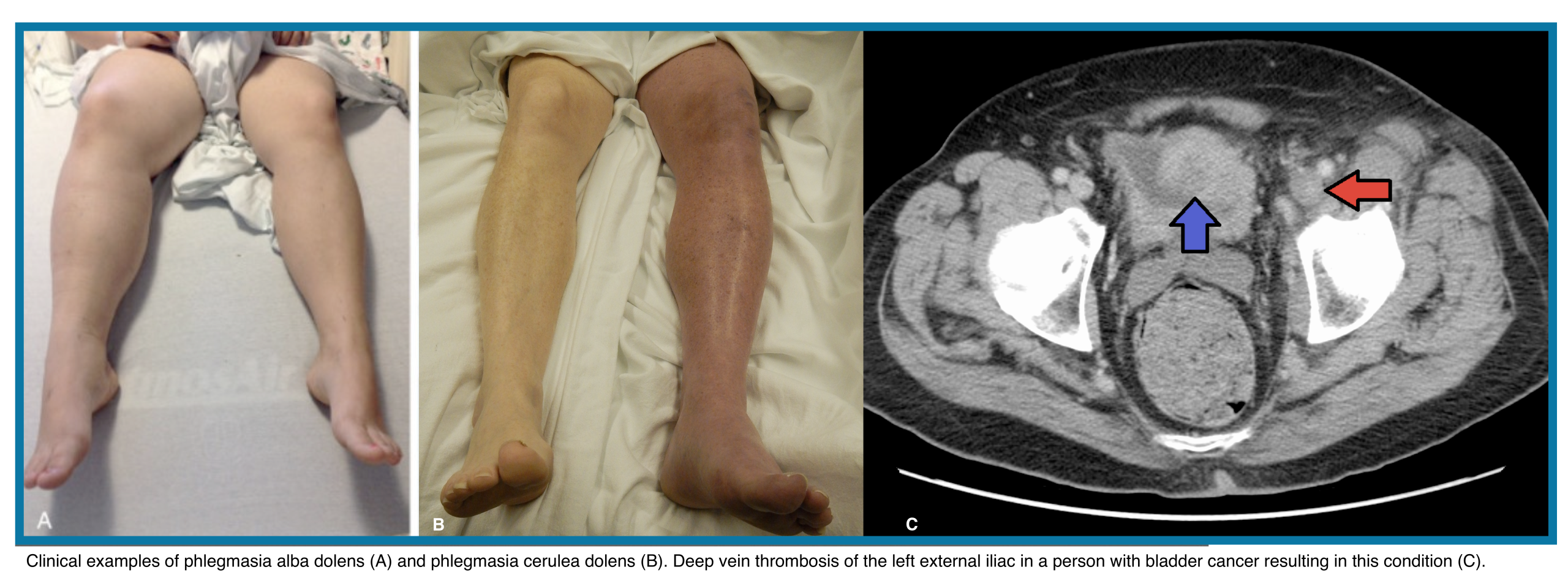

Clinical Presentation

Features of lower extremity DVT are nonspecific, and some patients are asymptomatic. Symptoms are usually unilateral but can be bilateral. In patients with isolated distal DVT, symptoms are confined to the calf, while patients with proximal DVT may have calf or whole-leg symptoms. Iliac vein thrombosis may present with massive swelling of the proximal part of the leg and buttock pain. Phlegmasia is an uncommon form of massive proximal DVT that can be limb-threatening and is discussed separately.

◾️DVT should be suspected in patients who present with leg swelling, pain, warmth, and erythema.

- Pain is the most frequent complaint.

- Patients may report only mild cramping or a sense of fullness in the calf.

- Other symptoms may include swelling and redness.

◾️Signs of extremity DVT

- Unilateral edema or swelling with a difference in calf or thigh circumferences.

- A difference in calf circumference is the most useful finding *.

- Localized tenderness along the vein (tender cords).

- Asymmetric pitting edema of the limb.

- Skin discoloration (erythema or cyanosis).

- Dilated superficial veins.

- Increased limb warmth.

Homans’ sign (calf pain on passive dorsiflexion of the foot) is unreliable for the presence of DVT

⚠️Limb-threatening occlusive thrombosis conditions (Right below figure):

- Phlegmasia alba dolens: Triad of edema, pain, and white blanching skin without cyanosis

- Phlegmasia cerulea dolens: Progression of phlegmasia alba dolens with cyanosis.

Differential Diagnosis of DVT

The classic presentation of unilateral leg pain, swelling, and erythema immediately raises concern for deep vein thrombosis (DVT). However, these signs are non-specific, and a broad differential exists. Accurate diagnosis requires considering a range of musculoskeletal, inflammatory, infectious, and vascular pathologies that can mimic DVT, ensuring appropriate management and preventing both unnecessary anticoagulation and missed critical diagnoses.

| Condition | Category | Distinguishing Features from DVT | Diagnostic Clues |

|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle Strain / Tear | Musculoskeletal |

• Pain specific to muscle movement • History of trauma or overuse • Swelling is localized, not whole limb • No venous distension |

• Tenderness at muscle belly • Pain on resisted contraction • Normal venous ultrasound |

| Baker’s (Popliteal) Cyst | Musculoskeletal |

• Pain/swelling localized to popliteal fossa • May cause calf swelling if ruptured • Often associated with knee arthritis |

• Transillumination possible • Ultrasound shows cystic structure • MRI confirms connection to knee joint |

| Cellulitis | Infection |

• Erythema is prominent and spreading • Fever and systemic symptoms common • Sharply demarcated warm area • Often portal of entry (cut, ulcer) |

• Leukocytosis, elevated CRP • No deep venous clot on ultrasound • Improves with antibiotics |

| Superficial Thrombophlebitis | Vascular |

• Palpable, tender cord-like vein • Linear erythema along vein course • Localized, not whole limb swelling |

• Ultrasound shows superficial clot • Deep veins are compressible • Often associated with varicose veins |

| Chronic Venous Insufficiency | Vascular |

• Bilateral symptoms common • Long-standing history • Skin changes: stasis dermatitis, hyperpigmentation • Worse at end of day, improves with elevation |

• No acute clot on ultrasound • Venous reflux on duplex • Often history of prior DVT |

| Lymphoedema | Lymphatic |

• Non-pitting edema (late stage) • Often bilateral • Skin thickening, “orange peel” appearance • Slow onset (months to years) |

• Stemmer’s sign positive • No venous abnormalities on ultrasound • MRI lymphangiography if needed |

| Congestive Heart Failure | Cardiac |

• Bilateral lower extremity edema • Associated dyspnea, orthopnea, PND • Elevated JVP, crackles on lung exam |

• BNP/NT-proBNP elevated • CXR showing pulmonary congestion • Echocardiogram with reduced EF |

| Compartment Syndrome | Orthopedic Emergency |

• Severe, out-of-proportion pain • Pain with passive stretch • Tense, swollen compartment • May have neurological deficits |

• Elevated intracompartmental pressure • History of trauma, fracture, or crush injury • Normal venous ultrasound |

| Ruptured Achilles Tendon | Musculoskeletal |

• Sudden “pop” or snap sensation • Inability to plantarflex foot • Palpable gap in tendon • Swelling localized to calf/ankle |

• Positive Thompson test • MRI or ultrasound shows tendon rupture • Normal venous studies |

| Peripheral Arterial Disease | Vascular |

• Pain with walking (claudication) • Pallor on elevation, dependent rubor • Decreased/absent pulses • Cool limb, shiny skin, hair loss |

• Ankle-brachial index (ABI) < 0.9 • Arterial duplex showing stenosis • Normal venous system |

| Hematoma | Trauma |

• History of trauma or anticoagulant use • Ecchymosis evident • Localized swelling, not whole limb • May have palpable mass |

• Ultrasound shows solid or complex fluid collection • No intravascular clot • May see active extravasation on CT |

| Tumor / Neoplasm | Oncologic |

• Insidious onset • Palpable mass • Constitutional symptoms (weight loss, fatigue) • No improvement with anticoagulation |

• Mass effect on imaging • Biopsy confirmation • May see extrinsic compression of veins |

Guideline References for DVT Differential Diagnosis (click to expand)

- Primary Diagnostic Guidelines:

- Kearon C, et al. Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-352.

- Stevens SM, et al. Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease: Second Update of the CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2021;160(6):e545-e608.

- NICE. Venous thromboembolic diseases: diagnosis, management and thrombophilia testing. NICE guideline [NG158]. 2020.

- Clinical Decision Rule Validation:

- Epidemiology of Alternative Diagnoses:

- Special Populations:

- Specific Mimics Literature:

- Carpenter PH, et al. Superficial thrombophlebitis of the lower limbs: a prospective analysis in 42 patients. J Mal Vasc. 2011;36(5):315-321.

- Bates SM, et al. A diagnostic strategy involving a quantitative latex D-dimer assay reliably excludes deep venous thrombosis. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(10):787-794.

The “3 C’s” of DVT Mimics: When evaluating unilateral limb swelling, systematically consider these three major categories:

1. Cellulitis – Look for fever, erythema, warmth, and a portal of entry (cut, ulcer, wound).

2. Congestive causes (CHF, renal failure, cirrhosis, hypoalbuminemia) – Typically cause bilateral, pitting edema and have associated systemic signs.

3. Chronic venous insufficiency – Long-standing history, skin changes (hyperpigmentation, stasis dermatitis), and swelling that worsens with dependency.

Key point: DVT can coexist with these conditions. In patients with moderate‑high clinical probability, imaging (duplex ultrasound) should not be deferred even if an alternative cause is suspected.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Pretest Probability Estimation

◾️Diagnosis of DVT (and PE) starts with an estimation of the pretest probability (PTP).

- PTP estimation helps guide the choice of diagnostic tests, the interpretation of results, and the need for follow-up testing.

- PTP estimation may be accomplished by the clinical gestalt of an experienced clinician or in conjunction with a clinical decision tool.

◾️Prediction tools

- Wells DVT Score👉 MDCalc 🧮

- This is the most commonly used and well-validated clinical decision tool for DVT.

- Wells’ DVT score and clinician gestalt have approximately equal diagnostic accuracy, and either method is acceptable.

- 🚨 Limitations to Note

- Subjective Components: “Alternative diagnosis” and “tenderness” require clinical judgment.

- Not for Upper Extremity DVT: Use different criteria (e.g., Constans Score 🧮) for arm DVT.

- Not validated in pregnant women.

- May use the LEFt score as a substitute for the Wells score in pregnant women *.

- Interpretation

- Although the Wells DVT score can categorize patients as low, intermediate, or high PTP, the decision to test with a highly sensitive D-dimer or venous US is dichotomous.

- Therefore, it is easiest and appropriate to combine low and intermediate probability groups and consider the PTP of DVT to be low (−2 to 2 points) or high (≥3 points).

- This is the most commonly used and well-validated clinical decision tool for DVT.

Wells Score for DVT (Compact)

Clinical prediction rule for estimating pre-test probability of lower extremity DVT

| Clinical Criteria | Points | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Active cancer (treatment within 6 months or palliative) | 1 | Patient on chemotherapy |

| Paralysis, paresis, or recent plaster immobilization | 1 | Stroke with leg weakness |

| Recently bedridden ≥3 days or major surgery within 4 weeks | 1 | Post-op hospitalization |

| Localized tenderness along deep venous system | 1 | Pain on femoral palpation |

| Entire leg swollen | 1 | Unilateral edema foot to thigh |

| Calf swelling >3 cm vs asymptomatic leg | 1 | Measurable asymmetry |

| Pitting edema in symptomatic leg | 1 | Unilateral pitting edema |

| Collateral superficial veins (non-varicose) | 1 | Visible superficial veins |

| Alternative diagnosis at least as likely as DVT | -2 | Cellulitis, Baker’s cyst |

Low (Score ≤ 0)

Pre-test Probability: ~3%

Action:

- D-dimer: if negative, rule out DVT

- If positive → ultrasound

Moderate (Score 1-2)

Pre-test Probability: ~17%

Action:

- D-dimer testing still useful

- If positive → ultrasound required

- Consider clinical context if negative

High (Score ≥ 3)

Pre-test Probability: ~75%

Action:

- Skip D-dimer

- Proceed directly to ultrasound

- Consider empiric anticoagulation if delay

| Wells Score | Pre-test Probability | Recommended ED Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| ≤ 0 | Low (~3%) | D-dimer → if negative: rule out. If positive: ultrasound. |

| 1-2 | Moderate (~17%) | D-dimer → ultrasound if positive. Consider context if negative. |

| ≥ 3 | High (~75%) | Skip D-dimer → direct to ultrasound. Consider empiric anticoagulation. |

- “Alternative Diagnosis” is the only criterion with negative points (-2). Use when another diagnosis (cellulitis, muscle tear) is equally or more likely.

- High score (≥3) = bypass D-dimer due to poor test characteristics in this group.

- Not validated for upper extremity DVT or pregnant patients (use LEFt score for pregnancy).

- Combine with clinical gestalt, especially in complex patients.

D-dimer

◾️High-sensitivity D-dimer assessment

- D-dimer has a sensitivity of ~ 97% and a specificity of ~39% *.

- A normal quantitative D-dimer concentration in a patient with a low PTP (e.g., Wells score −2 to 0) excludes proximal DVT with a sensitivity of approximately 92% and a specificity of 45%.

- This sensitivity is slightly lower than the sensitivity for PE, possibly because DVT tends to be subacute and therefore less prone to release D-dimer when diagnosed.

- The FDA has cleared numerous D-dimer assays for VTE diagnosis, but they are not uniform. Although 500 ng/mL is the most common cutoff for an abnormal result, assays can vary. Emergency clinicians must know their local lab’s specific validated threshold to correctly interpret results and safely exclude VTE.

◾️Age-adjusted D-dimer

- Using an age-adjusted cutoff in patients aged >50 years has been shown to reduce the need for venous US by 5%

- This is calculated by multiplying the patient’s age in years by 10 (mg/L), for an assay with a cutoff value of 500 mg/L.

- The safety of this strategy has not been tested with D-dimer assays with abnormal thresholds different than 500 ng/mL.

Radiographic Evaluation

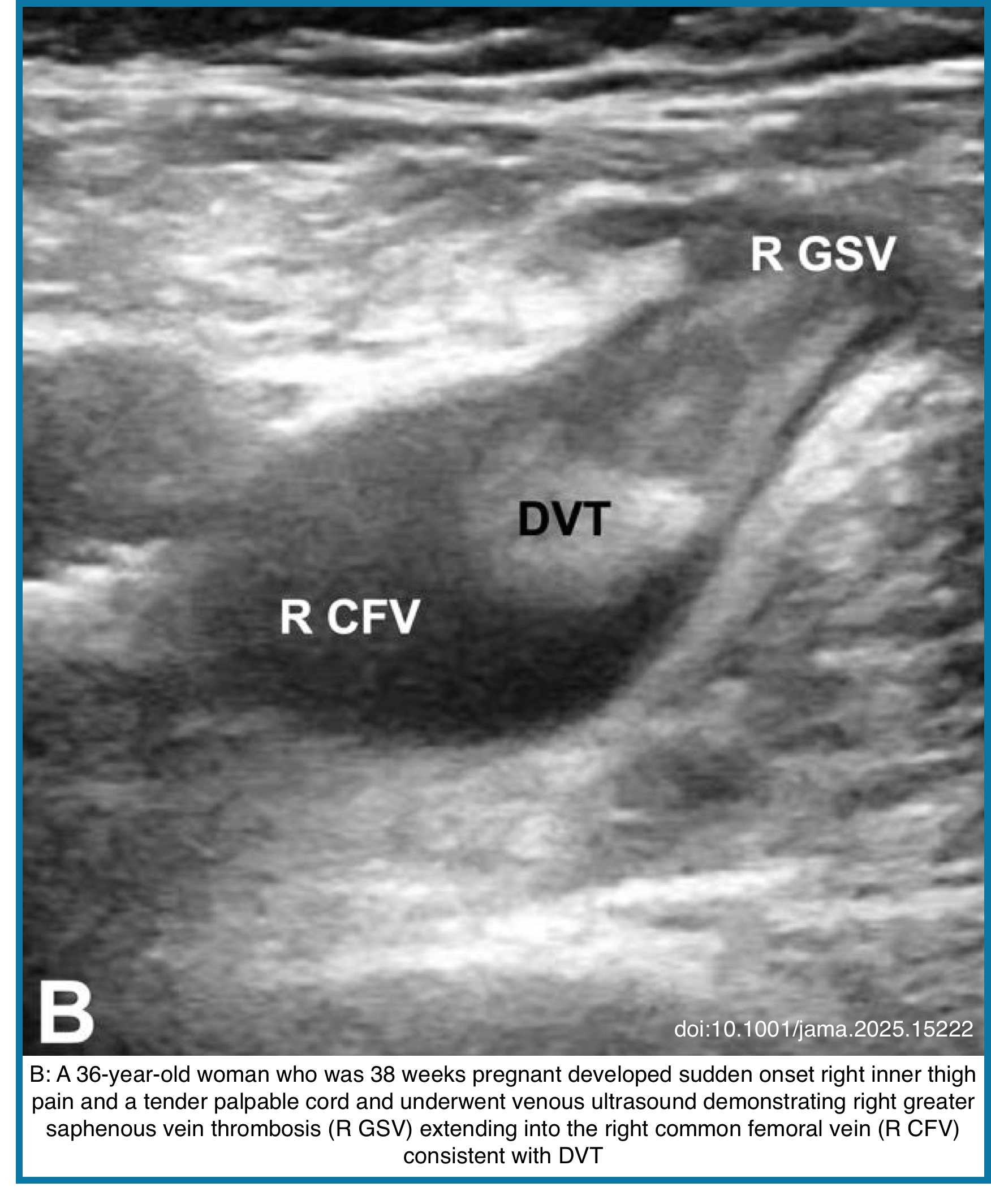

Venous Ultrasound

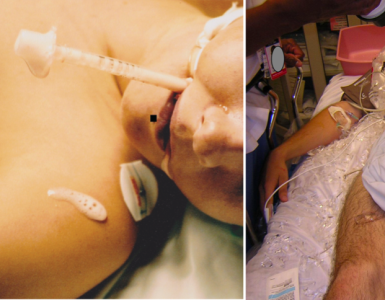

◾️DVT is characterized on US by the presence of heterogeneous echogenic materials filling the deep veins, indicative of thrombus formation *. On Doppler US, a decrease or absence of venous flow in the Doppler waveform patterns may further support a DVT diagnosis. One of the US findings indicative of DVT is decreased compressibility of the affected vessel. Normally, vessels should flatten when compressed under a US probe. However, in veins affected by DVT, the thrombus may prevent compression. While some cases of DVT involve the entire lumen and maintain a round shape under compression, partial DVT may cause the veins to deform but still include non-compressible areas where the thrombus is present.

- Patient Preparation: Frog Leg position → This enlarges the vein and brings it closer to the field of vision for the plane of the ultrasound probe

- Commonly used techniques are → Compression, Color Doppler, Augmentation, and Respiratory variation/phasic flow (on PWD mode).

- However, the studies have shown that compression is by far superior to the other methods.

◾️Several approaches to performing venous US are commonly used, and the emergency clinician should be aware of the US protocols used in their practice setting.

- Whole-leg US

- This is the criterion standard and combines compression US of the proximal veins with ultrasound of the calf and saphenous veins *.

- It uses compression, color Doppler, and spectral Doppler from the groin to the ankle.

- A single normal whole-leg ultrasound excludes DVT regardless of PTP.

- Three-point US, also called compression US (SN 95% and SP 95% for DVT).

- Scans the common femoral, femoral, and popliteal veins *.

- A negative three-point venous duplex ultrasound excludes the diagnosis of DVT in patients with low PTP.

- ⚠️However, for patients at high risk, a negative three-point ultrasound is inadequate to exclude DVT as a single test.

- Patients with high PTP can have DVT ruled out in the ED with a combination of a negative three-point ultrasound and a negative D-dimer.

- A patient with high PTP, an elevated (or not performed) D-dimer, and a negative three-point ultrasound should be referred for a repeat venous US in 5 to 7 days to ensure their symptoms are not due to a distal (calf vein) DVT that later propagates proximally.

- Two-point US

- Compression ultrasound, including the femoral vein 1 to 2 cm above and below the saphenofemoral junction and the popliteal vein up to the calf veins confluences *.

◾️POCUS performed by a trained emergency clinician is 90% to 95% accurate compared to radiology-performed US *,*.

- Test characteristics are highest for femoral veins and lowest for saphenous and popliteal veins *.

- POCUS of the upper extremity is not well studied and should be performed by radiology when necessary.

⚠️Limitations of the US: Can’t detect iliac or pelvic vein thrombosis.

Lower Extremity Venous Anatomy Flowchart

Visual guide from common femoral vein to calf trifurcation

- Femoral Vein (FV) – medial continuation

- Deep Femoral Vein (DFV) – lateral branch

Sonographic relationship: FV is deep to FA.

Vessels enter the adductor (Hunter’s) canal proximal to the knee.

Important reversal: PV is now superficial to Popliteal Artery (PA).

US Protocols for DVT Examination

DVT Ultrasound Examination Protocols

Comparison of whole-leg, 3-point, and 2-point compression ultrasound approaches

| Protocol | Location & Landmark | Steps & Structures | Key Action |

|---|---|---|---|

|

WHOLE-LEG

Complete Compression

Most comprehensive

|

Inguinal ligament to ankle

|

|

Compression + Doppler: Apply compression at 1-2 cm intervals. May use color or spectral Doppler for flow assessment.

|

|

3-POINT

Limited Compression

Recommended by POCUS 101

|

Three specific points:

|

|

Compression-only: Press until artery deforms. Vein should collapse completely. Incomplete collapse indicates DVT.

|

|

2-POINT

Rapid Screening

Fastest exam

|

Two compression points:

|

|

Focused compression: Rapid check at two key regions. Most proximal DVTs occur here. May need follow-up if negative.

|

Core Principles & Important Notes

Primary Diagnostic Method

Compression ultrasound is cornerstone. Apply pressure until adjacent artery deforms. Complete vein collapse = normal.

Patient Positioning

Use “Frog Leg” position: supine, knee bent, hip externally rotated. Enlarges veins for better scanning.

Safety Considerations

Theoretical risk of dislodging clot. Apply firm but careful pressure. Avoid forceful calf squeezing for Doppler.

Nomenclature Alert

(Superficial) Femoral Vein is part of deep venous system. Clot here = DVT requiring anticoagulation.

Acute vs. Chronic Clots

Acute thrombi often anechoic. Never rule out DVT by visualization alone—always compress.

Protocol Selection

3-point: balance of speed & accuracy. Whole-leg: comprehensive. 2-point: rapid screening.

What Can Be Mistaken for a DVT?

Several conditions mimic DVT on ultrasound or clinically:

- Superficial Thrombophlebitis: Clot in superficial veins. Differentiate by tracing vessel course.

- Baker’s Cyst: Popliteal synovial fluid collection. Compressible, non-vascular.

- Lymph Nodes: Inguinal nodes mimic non-compressible CFV. Look for fatty hilum.

- Hematoma: Post-traumatic blood collection. Lacks tubular structure.

- Pseudoaneurysm: Pulsatile with “to-and-fro” Doppler flow. History of arterial puncture.

- Muscle Tear: Pain/swelling but normal veins.

- Cellulitis: Skin changes, edema. Veins compress normally.

- Venous Insufficiency: Varicose veins, edema. Deep veins usually compressible.

Tip: Confirm you’re imaging a vein by identifying companion artery. Switch views: veins are circular in transverse, tubular in longitudinal.

CT Venography

CTV offers da efinite advantage of evaluating the pelvic veins and inferior vena cava (IVC), difficult to assess on US. Also, other clinical conditions that simulate pain and swelling, and incidental pelvic malignancy causing extrinsic venous compression can be detected concurrently on CTV *.

MRI Venography

- Gadolinium-enhanced MRV and magnetic resonance direct thrombus imaging (MRDTI) can be used to diagnose DVT. It can evaluate the pelvic vasculature and inferior vena cava (IVC), which is not possible with ultrasound.

- Although CT venography can also visualize the pelvic veins and IVC, the accuracy varies across studies, and CT exposes patients to ionizing radiation.

- MRV is reserved for specific situations, such as:

- Evaluating pelvic/abdominal veins in pregnant patients (to avoid radiation).

- Patients with severe contrast allergies.

- Differentiating acute from chronic thrombus when it impacts management (can help characterize thrombus age).

- Key Advantages: No ionizing radiation; excellent soft-tissue contrast.

- Considerations: Limited availability; longer scan time; higher cost; not first-line for routine lower extremity DVT.

Summary of radiologic diagnostic modalities

Primary Imaging Modalities for DVT Diagnosis

Comparison of radiological methods for detecting deep venous thrombosis

| Modality | Primary Role & Indication | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compression Ultrasound First-line for symptomatic lower extremity DVT | Initial imaging for leg swelling, pain, tenderness. Includes 2-point, 3-point, and whole-leg protocols. |

|

|

| CT Venography First-line for iliac/IVC thrombosis or concurrent PE | Suspected pelvic vein/IVC thrombosis, combined PE+DVT assessment, trauma patients. |

|

|

| MR Venography Problem-solving for complex cases | Suspected iliac/IVC thrombosis with CT contraindications, pregnancy, distinguishing acute from chronic clot. |

|

|

| Contrast Venography Historical gold standard, now rarely used diagnostically | Primarily during interventional procedures, rarely for diagnosis when other modalities inconclusive. |

|

|

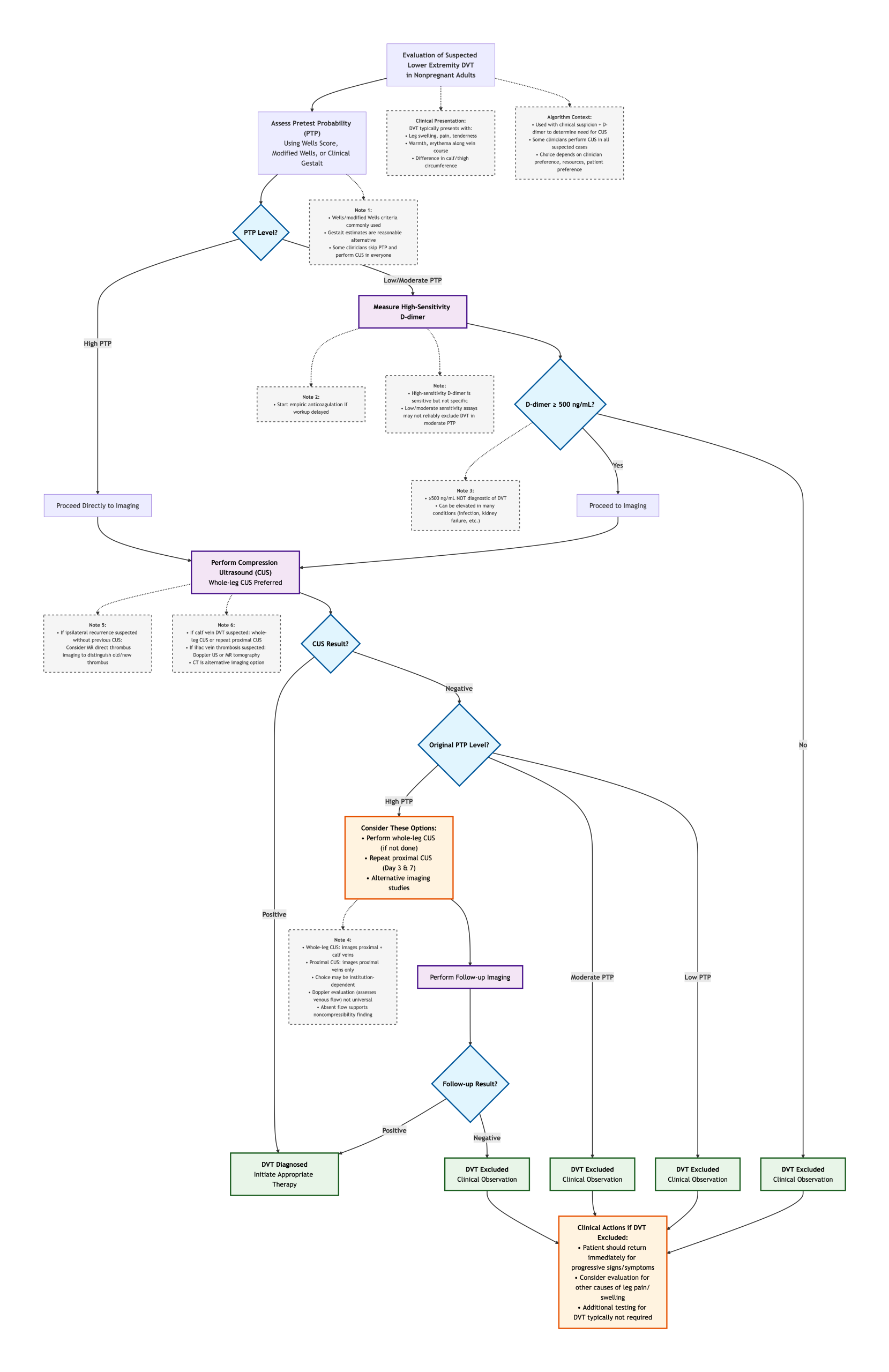

Diagnostic Approach

When minutes matter, and clinical signs can be misleading, a clear diagnostic pathway is essential. The following algorithm distills the complex decision-making for suspected DVT into a simple, efficient flow. Starting with clinical probability and strategically employing the high-sensitivity D-dimer, it filters patients toward or away from definitive imaging with precision, ensuring timely treatment for those in need and avoiding over-testing for those at low risk.

Management Principles

Anticoagulation

◾️Phases of anticoagulation. Anticoagulant therapy for acute DVT is often divided into three phases:

- The initiation phase (or initial therapy) uses parenteral or higher-dose oral agents.

- 🎯Goal: To control acutely propagating thrombus and prevent extension or embolization.

- The maintenance phase (also called “treatment” or “long-term” phase) of anticoagulation therapy is administered for a finite period beyond initiation, usually 3 to 6 months and occasionally up to 12 months.

- 🎯The goal of this phase is to stabilize the thrombus during recovery while intrinsic thrombolysis takes place.

- The extended phase (indefinite) of anticoagulation therapy is administered beyond the finite period, sometimes indefinitely (eg, without a planned stop date).

- 🎯The goal of this phase is secondary prevention.

- Extended-phase therapy includes periodic reassessment of the risks and benefits of continuing anticoagulation.

◾️For more on anticoagulants, see here.

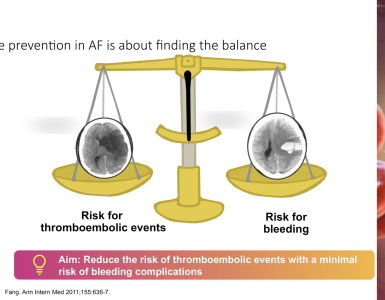

Pre-treatment assessment of bleeding risk

- Before initiation of anticoagulation for VTE, emergency clinicians should assess the patient’s risk of bleeding.

- 💡This is particularly important for patients with calf vein DVT without PE, or isolated subsegmental PE without DVT, for whom withholding anticoagulation may be reasonable.

- Before initiating treatment, consider the absolute (and relative) contraindications for anticoagulation (see below).

Contraindications to Anticoagulation for DVT

Absolute and relative contraindications that impact the decision to initiate anticoagulant therapy

| Category | Specific Contraindications | Clinical Details & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

|

ABSOLUTE

Generally prohibit anticoagulation

|

|

|

|

RELATIVE

Require risk-benefit analysis

|

|

|

Absolute contraindications generally prohibit anticoagulation initiation and necessitate urgent specialty consultation (hematology, vascular surgery). In patients with acute proximal DVT and an absolute contraindication, consider IVC filter placement as a bridge to anticoagulation once the contraindication resolves.

Relative contraindications require careful individualized risk-benefit analysis. Factors to consider include: DVT location/proximity, thrombus burden, embolic risk, bleeding severity/recurrence risk, and availability of safer anticoagulant options. Shared decision-making with the patient is essential.

- Bleeding risk can also be assessed using the validated score.

- At DVT Diagnosis (Day 0): Use HAS-BLED.

- Goal: Not to withhold treatment, but to “flag and fix” modifiable risks (e.g., control hypertension, stop NSAIDs, address alcohol use).

- Action: A high score (≥3) prompts caution and closer monitoring, but should not prevent initiating necessary anticoagulation for a proximal DVT.

- At 3-Month Decision Point (for Unprovoked DVT): Use VTE-BLEED.

- Goal: To inform the stop vs. continue decision for extended therapy.

- Interpretation: A low VTE-BLEED score (0-1 points) identifies patients at low bleeding risk who are good candidates for continuing anticoagulation. A high score suggests caution.

- Action: Combine with a recurrence risk assessment (e.g., D-dimer, clinical prediction tools) to balance risks.

- At DVT Diagnosis (Day 0): Use HAS-BLED.

Essential Bleeding Risk Scores for Anticoagulation

Two key validated scores for assessing long-term bleeding risk in different clinical scenarios

| Score | Components & Scoring | Clinical Application & Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

|

HAS-BLED

Atrial Fibrillation

Long-term risk assessment |

|

|

|

VTE-BLEED

Venous Thromboembolism

Extended therapy decisions |

|

|

HAS-BLED is the most commonly used score for assessing bleeding risk in atrial fibrillation patients. A high score should prompt correction of modifiable factors but does NOT contraindicate anticoagulation. For patients with high stroke risk (CHA₂DS₂-VASc ≥2), anticoagulation is generally recommended regardless of HAS-BLED score, with appropriate risk mitigation.

VTE-BLEED helps clinicians decide whether to continue anticoagulation indefinitely or limit treatment duration after the initial 3-month period for VTE. This score is particularly useful for patients with unprovoked VTE where the decision between extended vs. limited therapy requires careful balancing of recurrence risk versus bleeding risk.

IVC Filter

- Benefit: Might intercept clots traveling to the lungs (thereby avoiding pulmonary embolism).

- Harm

- Blood stasis increases the risk of DVT.

- Filter thrombosis within the IVC.

- Filter penetration of the IVC wall

- Filter embolization (to the right ventricle or lungs).

- Filter fracture.

- IVC Filter Indications:

- Inability to receive anticoagulation (absolute contraindication)dications for anticoagulation).

- (Sub)massive PE with a low hemodynamic reserve.

- Known DVT with large clot burden (especially large, free-floating, proximal DVT).

- Retrieval is MANDATORY

- Remove within 25–54 days (optimal window)

- Complication rates increase dramatically after 3 months:

- 25% cannot be retrieved after 6 months

- Filter thrombosis: 3–11%

- DVT recurrence: 12–20%

-

Filter migration/perforation: 2–5%

Stepwise Guide to DVT Treatment Initiation

◾️Step 1: Immediate First Actions & Absolute Contraindication Check

- 1A. Assess for Life-Threatening Presentation

- Rule out phlegmasia cerulea dolens (vascular surgery emergency) or concurrent massive PE.

- 1B. Screen for Absolute Contraindications to Anticoagulation: This is the first and most critical bleeding risk assessment.

- Action: If an absolute contraindication exists, consult hematology/vascular surgery immediately.

- Consider IVC filter placement only in this specific scenario, with a plan for retrieval once anticoagulation can be started.

◾️Step 2: Determine DVT Type & Initial Pathway (Influenced by Bleeding vs. extending thrombosis Risk)

- Proximal DVT

- Initial Management Decision (Integrating Bleeding Risk): Proceed to anticoagulation (Step 3).

- Bleeding risk will guide agent choice and dosing.

- Initial Management Decision (Integrating Bleeding Risk): Proceed to anticoagulation (Step 3).

- Isolated Distal (Calf) DVT: Pause. Bleeding risk is a key determinant of the chosen pathway (see below).

◾️Step 3: Formal Bleeding Risk Assessment & Anticoagulant Selection

- 3A. Calculate a Structured Bleeding Risk Score: The HAS-BLED score is the most validated in VTE patients starting anticoagulation.

- Components

- Hypertension, Abnormal renal/liver function, Stroke, Bleeding history, Labile INR (if on warfarin), Elderly (>65), Drugs/alcohol.

- Interpretation

- A score of ≥3 indicates high risk. The purpose is not to withhold therapy but to identify and modify risk factors (e.g., control BP, review NSAIDs/antiplatelets, treat alcohol misuse, manage labile INR).

- Components

- 3B. Select Initial Anticoagulant with Bleeding Risk in Mind:

- For most patients, DOACs (apixaban, rivaroxaban, etc.) are preferred over warfarin due to a lower risk of intracranial and fatal bleeding.

- Rivaroxaban and apixaban do not require bridging with LMWH and are the first-choice anticoagulants for most patients with DVT.

- Protocols that use monotherapy with a DOAC can facilitate outpatient management

- In high bleeding risk (HAS-BLED ≥3):

- Ensure modifiable risks are addressed.

- Consider Apixaban

- In meta-analyses, apixaban (5mg BID) has shown a favorable bleeding profile, particularly for major GI bleeding compared to other DOACs.

- Avoid certain agents: Rivaroxaban may be associated with a higher GI bleed risk; use with caution in patients with prior GI bleeding or active gastritis.

- In severe renal impairment (CrCl <15-30 mL/min), bleeding risk is inherently higher. Avoid DOACs; use LMWH (with dose monitoring) or warfarin.

- For most patients, DOACs (apixaban, rivaroxaban, etc.) are preferred over warfarin due to a lower risk of intracranial and fatal bleeding.

- Active Cancer: LMWH is first-line. DOACs are effective alternatives but use with caution in GI malignancies.

- Reversal: Specific agents exist for DOACs. Bleeding on DOACs is often less severe than on warfarin.

- Avoid DOACs in: Pregnancy, severe renal/liver failure, antiphospholipid syndrome, and high-risk PE.

Step 4: Disposition Decision & Coordination

Step 4: Disposition Decision & Coordination

The critical ED pivot point for DVT management. Use the following criteria to determine safe disposition based on clinical and social factors.

| Disposition | Clinical Criteria | ED Actions Prior to Disposition |

|---|---|---|

| Home with DOAC |

|

|

| Observation / Short-Stay |

|

|

| Inpatient Admission |

|

|

◾️Step 5: Implement Adjunctive Measures (Bleeding-Aware)

- Mobilization

- Encourage early ambulation; does not increase PE risk.

- Pharmacist Review

- Critically review concomitant medications. Stop or substitute NSAIDs, antiplatelets (if not absolutely required), and other anticoagulants.

- Symptom Control: Prescribe analgesia (avoid NSAIDs).

- Patient Education

- Counsel on bleeding signs (melena, hematuria, bruising, headache), the imperative of compliance (especially with DOACs), and avoidance of OTC drugs that increase bleeding risk.

-

Compression: Consider knee-high compression stockings for symptomatic relief only.

◾️Step 6: Special Considerations & Referrals

- Iliofemoral DVT

- Admit. Consider a vascular consult for catheter-directed thrombolysis if symptoms are <14 days and low bleeding risk.

- IVC Filter

- Only if an absolute contraindication to anticoagulation exists. Plan for retrieval.

◾️Step 7: Plan Follow-Up & Duration (A Dynamic Risk/Balance)

The decision for extended therapy (>3 months) for an unprovoked DVT is a direct balance of Recurrence Risk vs. Bleeding Risk.

- At the 3-month mark, re-evaluate:

- Recurrence Risk: Unprovoked DVT, male sex, positive D-dimer after stopping therapy, and presence of antiphospholipid antibodies.

- Bleeding Risk: Recalculate HAS-BLED, review comorbidities.

- Decision Aid

- If recurrence risk outweighs bleeding risk (e.g., low HAS-BLED score), recommend extended therapy.

- Bleeding-Sparing Extended Regimen

- For patients on extended therapy where bleeding is a concern, reduced-dose DOAC regimens are evidence-based options (e.g., Apixaban 2.5 mg BID or Rivaroxaban 10 mg daily) to lower bleeding risk while maintaining efficacy.

Specific Situation

Limb-threatening DVT

Isolated Calf Vein Thrombosis

◾️Calf vein thrombosis itself isn’t dangerous, but it can propagate proximally to cause a DVT.

- About 15% of untreated isolated calf-vein DVT will extend into the popliteal vein or more proximally.

- Anticoagulation lowers the rate of proximal propagation and embolization.

◾️ Decision to anticuagulate or not?

- It is not known whether the benefit of anticoagulation outweighs the risk, nor is it known whether anticoagulation is superior to a strategy of serial venous ultrasound with anticoagulation reserved for DVT that propagates proximally.

- Distal DVT with features associated with high proximal extension risk should lead the emergency clinician to favor anticoagulation. Risk for extension includes:

- Symptoms (other than minor ones)

- Presence of symptoms (swelling or edema, pain, warmth) is a significant risk factor for proximal extension and embolization

- Thrombus into or close to the popliteal vein (eg, within 1 to 2 cm) or involving the tibio-peroneal trunk

- Extensive thrombosis involving multiple veins (eg, >5 cm in length, >7 mm in diameter), or bilateral disease

- D-dimer ≥500 ng/mL

- Unprovoked DVT (DVT occurring in the absence of identifiable risk factors)

- Persistent/irreversible risk factors, such as active cancer or prolonged immobility *

- Previous DVT or pulmonary embolism

- Inpatient status

- COVID-19, especially severe disease

- Symptoms (other than minor ones)

- High bleeding risk favors surveillance without anticoagulation.

- When treatment with anticoagulation is used for isolated calf vein thrombosis, the dosing regimen is the same as for proximal DVT.

◾️Risk Stratify the Calf DVT & Integrate Bleeding Risk

- The decision matrix for isolated distal DVT now has two axes:

- Risk of Extension (High vs. Low – as previously defined).

- Risk of Major Bleeding (High vs. Low).

◾️Management Pathway Decision:

- Anticoagulate if: High risk of extension OR (Low risk of extension but also Low bleeding risk and patient preference favors treatment).

- Serial Surveillance (Observe) if: Low risk of extension AND High bleeding risk. This is a guideline-recommended strategy to avoid anticoagulant exposure in high-bleed-risk patients with a low-threat clot.

- Shared Decision-Making is crucial to weigh the small risk of extension against the individual’s bleeding risk.

Superficial Vein Thrombophlebitis (SVT)

◾️SVT is a common clinical condition involving thrombosis in the superficial venous system, often with inflammation (superficial thrombophlebitis).

◾️Epidemiology & Risk Factors

- Incidence: ~1.3–1.8 per 1,000 person-years.

- Commonly affected veins: Great saphenous vein (GSV), small saphenous vein (SSV), and varicose veins.

- Risk factors *

- Varicose veins

- Recent venous intervention/surgery

- Intravenous catheter use

- Cancer

- Pregnancy/postpartum

- Immobility

- Thrombophilia

- Hormonal therapy (OCPs, HRT)

- Obesity

- Previous VTE

- 💡Vein thrombosis in the absence of venous insufficiency should prompt a workup for occult malignancy and hypercoagulability.

- SVT is most common in the great saphenous and small saphenous veins of the lower extremities, and the basilic and cephalic veins of the upper extremities *. SVT can also manifest in the chest wall, breasts, or penis (Mondor disease).

◾️Clinical Presentation

- Symptoms: Pain, redness, warmth, palpable cord (sometimes nodular cord) along the known course of a superficial, typically varicose vein.

- The persistence of the palpable cord when the extremity is raised suggests the presence of a thrombus.

- Remember that superficial veins can be several centimeters below the surface of normal-appearing skin, particularly in individuals with obesity. Patients may complain of pain (e.g., along the inner medial thigh) but have minimal physical findings (i.e., no erythema or palpable cord).

- Signs: Erythema, induration, tenderness.

- Low-grade fever may be present in uncomplicated superficial thrombophlebitis, but high fever should increase suspicion for suppurative superficial thrombophlebitis.

◾️Differential diagnosis

- Confirmation of suspected SVT with Duplex Ultrasonography is often useful because the following conditionscan present with similar signs and symptoms to SVT *.

- Cellulitis

- Erythema nodosum

- Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa

- Tendinitis

- Kaposi sarcoma

- Popliteal (Baker) cyst (clue: patients who complain of pain behind the knee without the typical obvious phlebitis)

- Phlebitis without thrombosis

- DVT

- Lymphangitis

- localized soft tissue infections

- Hematomas

◾️Complications. Historically considered benign, but recent evidence shows a significant risk of complications, including:

- Extension of thrombosis.

- DVT and PE (~10% of patients with SVT progress to DVT or PE) *.

- SVT and DVT can coexist (synchronous) either as contiguous extensions of thrombus (via the saphenofemoral junction, saphenopopliteal junction, or perforating veins) or as a noncontiguous finding. Synchronous thrombus can happen remote from the location of the SVT, and even thrombosis in the contralateral extremity.

- In addition to well-established risk factors for DVT (above), factors predicting a diagnosis of DVT when SVT is identified on physical examination include *

- Age >60 years

- Male sex

- Bilateral SVTs

- Presence of systemic infection

- Absence of varicose veins

- Recurrent or migratory thrombophlebitis

- Thrombosis of the lower extremity superficial veins can occur as an isolated event, but can be recurrent in the same vein.

- Migratory thrombophlebitis. In some patients, distinctly different vein segments can be affected over time. When this occurs without an identifiable cause, it is referred to as migratory thrombophlebitis. Migratory thrombophlebitis can be associated with an underlying malignancy, particularly carcinoma of the pancreas

- Suppurative thrombophlebitis. It should be suspected when erythema extends significantly beyond the margin of the vein.

◾️Diagnosis

- Clinical diagnosis is often sufficient in typical cases.

- Duplex Ultrasound (DUS) is recommended to:

- Confirm diagnosis

- Assess extent (length, proximity to deep system)

- Rule out concurrent DVT

- Evaluate for varicose veins

- Laboratory tests: D-dimer testing has a sensitivity of approximately 48% to 74.3% and, therefore, is not reliable for excluding SVT *.

◾️Management

- Treatment of phlebitis

- For all patients with phlebitis, symptomatic care measures should be instituted, including extremity elevation, warm or cool compresses,

compression stockings, and pain management.

- For all patients with phlebitis, symptomatic care measures should be instituted, including extremity elevation, warm or cool compresses,

- Monitoring

- Patients should undergo repeat physical examination within 7 to 10 days of their initial diagnosis to evaluate for resolution or progression. Any worsening of Clinical symptoms or extension of signs of phlebitis on physical examination should prompt a duplex ultrasound.

- Anticoagulation

- A decision for anticoagulation is based on the patient’s risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE), which can be stratified as low, intermediate, or elevated. Risk-stratification of the disease is generally based on underlying etiology, length of thrombosis, and distance from the deep venous system:

- Low risk (symptomatic management with topical or oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications)

- SVT remote (>3 cm) from the deep venous system, i.e., from the saphenofemoral junction or saphenopopliteal junction (eg, below the knee great saphenous vein)

- Focal SVT with axial vein involvement (ie, ≤5 cm in length).

- No other medical risk factors for DVT.

- Associated with intravenous cannulation.

- Intermediate risk (typically prophylactic-dose anticoagulation, e.g., 40 mg enoxaparin subcutaneously or 10mg rivaroxaban orally once-daily) for 45 days rather than supportive care alone

- SVT in proximity (3 to 5 cm) to the deep venous system, particularly if involving the great or small saphenous vein.

- SVT that is more extensive with the affected vein segment (≥5 cm).

- SVT that propagates with symptomatic care, and the patient has no medical risk factors for VTE.

- High risk (therapeutic anticoagulation rather than prophylactic anticoagulation with a dose and duration like that selected for DVT).

- SVT is identified initially or subsequently propagates within 3 cm of the deep venous system, particularly if involving the great saphenous vein or small saphenous vein.

- SVT that propagates despite prophylactic anticoagulation given for an intermediate-risk SVT

- Recurrent SVT after cessation of anticoagulation.

- SVT in a patient with medical risk factors for VTE (eg, prior DVT, thrombophilia).

- Low risk (symptomatic management with topical or oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications)

- A decision for anticoagulation is based on the patient’s risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE), which can be stratified as low, intermediate, or elevated. Risk-stratification of the disease is generally based on underlying etiology, length of thrombosis, and distance from the deep venous system:

◾️Initial Symptomatic Treatment:

- Distal SVT (below the knee) is adequately managed with NSAIDs and warm compresses.

- Analgesia and anti-inflammatory properties help reduce local pain, redness, and swelling.

- Risk of Progression & Standard Follow-up:

- The rate of DVT or PE within three months of superficial thrombophlebitis is approximately 3%.

- Therefore, all patients with superficial vein thrombosis should be scheduled for a follow-up ultrasound in about 7 days to evaluate for progression or extension.

- Special Case: Greater Saphenous Vein (GSV) Thrombosis:

- When SVT involves the greater saphenous vein and extends above the knee, the clot is at risk of progressing to a DVT via the saphenous-femoral junction.

- For these patients, evidence from a large randomized controlled trial supports a 45-day course of prophylactic-dose anticoagulation (e.g., low-dose fondaparinux or LMWH).

- This regimen significantly reduces the risk of clot extension, DVT, and PE, though the absolute rate of PE in these patients is less than 1% with or without treatment.

- High-Risk Scenario Warranting Full Treatment:

- If a GSV clot is proximal (within 3 cm of its junction with the common femoral vein), the risk of extension into the deep venous system is high (approximately 25%).

- In this specific case, therapeutic (full-dose) anticoagulation is warranted for at least 30 days, as this is managed as a high-risk condition akin to a standard DVT.

Superficial Vein Thrombosis (SVT): A Specific Situation in Venous Thromboembolism

Differentiating SVT from DVT, risk stratification, and evidence-based management

| Clinical Aspect | Key Features & Criteria | Management Implications |

|---|---|---|

|

DIAGNOSIS

Differentiating SVT from DVT

|

|

|

|

RISK FACTORS

Predicting Complication Risk

|

|

|

|

TREATMENT

Risk-Based Anticoagulation

|

LOW RISK

Below-knee, <5cm, >5cm from junction, no risk factors

INTERMEDIATE RISK

3-5cm from junction, ≥5cm length, propagation on NSAIDs

HIGH RISK

<3cm from junction, recurrent, DVT risk factors present

|

|

|

WARNINGS

Don’t Miss These

|

|

|

1. SVT is NOT benign: Up to 53% have concurrent DVT; 1-33% PE risk. Always rule out DVT with duplex.

2. Distance dictates dosing: <3cm from saphenofemoral junction = therapeutic anticoagulation; 3-5cm = prophylactic; >5cm = monitor.

3. Length matters: Thrombus ≥5cm requires anticoagulation consideration regardless of distance.

4. Absent varicose veins = workup needed: Screen for malignancy (especially pancreatic) and thrombophilia.

5. CALISTO trial evidence: 45 days of fondaparinux 2.5mg daily reduces VTE from 5.9% to 0.9% in intermediate-risk SVT.

6. SURPRISE trial option: Rivaroxaban 10mg daily ×45 days is non-inferior to fondaparinux for oral preference.

7. Monitor progression: Repeat duplex in 7-10 days if not anticoagulated; any propagation = escalate therapy.

Upper Extremity DVT

◾️Definition & Clinical Significance

Upper extremity deep vein thrombosis (UEDVT) refers to thrombus formation in the deep venous system of the arm, including the brachial, axillary, subclavian, and brachiocephalic veins, and may extend into the superior vena cava. While historically considered rare, the incidence has risen significantly due to the increased use of central venous access devices (CVADs), particularly peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs). UEDVT carries notable risks, including pulmonary embolism (PE) in 2–9% of cases and the potential for post-thrombotic syndrome (PTS) in the upper limb, impacting quality of life and limb function.

◾️Epidemiology & Etiology

- Primary vs. Secondary UEDVT

- Primary (Spontaneous) UEDVT: Accounts for approximately 20–30% of cases. Often related to anatomical abnormalities (e.g., venous thoracic outlet syndrome) or strenuous, repetitive arm activity (Paget-Schroetter syndrome). May also be idiopathic.

- Secondary (Catheter-Associated) UEDVT: Represents 70–80% of all UEDVT cases. Strongly associated with indwelling venous catheters, particularly:

- Peripherally Inserted Central Catheters (PICCs)

- Tunneled Central Venous Catheters (CVCs)

- Implanted Ports

- Reported Incidence

- In patients with malignancy, the incidence of catheter-associated thrombosis ranges from 1% to 66%, varying by catheter type, insertion technique, and screening practices.

- Asymptomatic DVT detected via routine ultrasound screening in cancer patients with catheters may exceed 50%.

◾️Risk Factors. Risk is multifactorial, involving patient, catheter, and disease-related factors.

- Patient-Related Factors:

- Active cancer (especially hematologic and lung malignancies)

- Personal or family history of VTE

- Inherited thrombophilia (e.g., Factor V Leiden, Prothrombin G20210A mutation)

- Hospitalization for acute medical illness or critical care admission

- Pregnancy and postpartum period

- Hormonal therapy (oral contraceptives, hormone replacement, tamoxifen)

- Catheter-Related Factors:

- Catheter Type: PICCs carry a higher risk compared to implanted ports or centrally inserted CVCs. Multi-lumen catheters confer greater risk than single-lumen.

- Catheter-to-Vein Ratio: A ratio >45% significantly increases thrombosis risk. Optimal practice targets a ratio <33% when possible.

- Insertion Site: Subclavian or cephalic vein access may have higher thrombosis rates compared to internal jugular or basilic veins.

- Catheter Tip Malposition: Tips terminating in the brachiocephalic vein (vs. the superior vena cava/right atrial junction) are associated with markedly increased thrombosis risk.

- Infection: Catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI) is an independent risk factor for concurrent thrombosis.

◾️Clinical Presentation & Diagnosis

- Clinical Features

- Asymptomatic

- Common, especially in catheter-associated cases, is discovered on screening.

- Symptomatic:

- Local: Unilateral arm swelling, pain, erythema, warmth, and dilated superficial collateral veins over the chest/shoulder.

- Catheter Dysfunction: Inability to aspirate blood or infuse fluids (“withdrawal occlusion” often due to a fibrin sheath).

- PE-related: Dyspnea, chest pain, tachycardia, hypoxemia (PE occurs in ~6% of UEDVT cases).

- Superior Vena Cava (SVC) Syndrome: Facial/neck swelling, headache, dyspnea (with proximal clot extension).

- Asymptomatic

◾️Complications & Initial Treatment:

- UEDVT can cause Pulmonary Embolism (PE). The incidence is 5–8%, though PEs from this source tend to be less severe.

- All patients with DVT above the elbow require definitive treatment with therapeutic anticoagulation, prescribed at the same doses used for lower extremity DVT.

◾️Diagnostic Algorithm

- Initial Testing

- Compression Ultrasonography (CUS) is the first-line imaging modality. It is non-invasive, readily available, and has high sensitivity/specificity for axillary and more distal veins.

- If CUS is Negative but Clinical Suspicion Remains High: Consider imaging the central thoracic veins (subclavian, brachiocephalic, SVC) with:

- CT Venography (CTV)

- MR Venography (MRV)

- Conventional Contrast Venography (the historical gold standard)

- Role of D-Dimer

- It has high sensitivity but poor specificity for UEDVT. A negative D-dimer may help rule out DVT in low-probability outpatients but is not reliable in hospitalized patients or those with cancer.

◾️Management

1. Anticoagulation Therapy

- First-line treatment for acute UEDVT is therapeutic anticoagulation, regardless of etiology (primary or secondary), to prevent thrombus extension, PE, and PTS.

- Recommended Agents & Duration (ASH 2020/CHEST 2021):

- Initial Treatment (First 5–10 days): Parenteral anticoagulant (LMWH, fondaparinux, or IV UFH).

- Long-term Treatment (Minimum 3 months):

- For Cancer-Associated UEDVT: Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs: apixaban, rivaroxaban, edoxaban) or LMWH are preferred over warfarin.

- For Non-Cancer UEDVT: DOACs or vitamin K antagonists (VKA) are acceptable.

- Extended Therapy (>3 months): Consider if the provoking factor (e.g., active cancer, indwelling catheter) persists or in cases of unprovoked/recurrent VTE, balancing against bleeding risk.

2. Catheter Management

- If the Catheter is Functional and needed: Continue anticoagulation with the catheter in situ. Removal is not mandatory.

- If the Catheter is Non-Functional, Infected, or No Longer Needed: Remove the catheter after at least 3–5 days of therapeutic anticoagulation to reduce embolization risk.

- Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis (CDT): Consider in select patients with acute (<14 days), symptomatic, extensive (e.g., axillo-subclavian) DVT, low bleeding risk, and good functional status to reduce PTS risk. Not recommended for routine use.

3. Special Considerations

- Isolated Brachial Vein DVT: Management is controversial. Anticoagulation is often recommended, especially if symptomatic, but shorter courses may be considered.

- Contraindications to Anticoagulation: Consider catheter removal alone. IVC/SVC filters are rarely indicated and only in absolute contraindications with high PE risk.

- Superficial Vein Thrombosis (SVT) of the Upper Extremity: Treat with NSAIDs for pain. Consider prophylactic-dose anticoagulation for 45 days if the thrombus is >5 cm long, close to the deep junction, or in high-risk patients.

Pregnancy

◾️Epidemiology & Risk

- Pregnancy increases VTE risk 4-5×; the postpartum period carries the highest risk

- 90% of pregnancy DVTs occur in the left leg due to anatomical compression (May-Thurner physiology)

- Risk peaks in the 3rd trimester and the first 6 weeks postpartum

◾️Clinical Presentation

- Symptoms overlap with normal pregnancy: leg swelling, pain, warmth

- 🚩Red flags: Unilateral leg swelling (especially left), calf pain, swelling above the knee

- Pelvic vein thrombosis may present with flank/buttock pain

◾️Diagnosis

- Compression ultrasound (CUS) is first-line

- Whole-leg ultrasound preferred over proximal-only

- Perform in the left lateral decubitus position in late pregnancy

- D-dimer use is limited: Levels rise normally in pregnancy; cutoff unclear

- Clinical prediction rule: “LEFt” mnemonic → Left leg, Edema (≥2 cm difference), First trimester presentation (see below).

- If ultrasound negative but suspicion high → consider Doppler of iliac veins or MR venography

LEFt Clinical Prediction Rule for DVT in Pregnancy

A validated tool for assessing pre-test probability of deep vein thrombosis in pregnant and postpartum women

LEFt Score Calculation

| Clinical Criteria | Points | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Left leg symptoms (unilateral left leg swelling/pain) | +2 | Left calf larger than right |

| Edema ≥2 cm difference at tibial tuberosity | +1 | Measurable calf asymmetry |

| First trimester presentation (≤12 weeks gestation) | +1 | DVT symptoms at 10 weeks |

| Previous VTE (DVT or PE) | +1 | History of DVT 2 years prior |

LEFt Score = 0

Pre-test Probability: Very Low (~3%)

Recommended Action:

- D-dimer testing can be considered*

- If D-dimer negative → DVT effectively ruled out

- If D-dimer positive → Proceed to compression ultrasound

*Note: D-dimer specificity is reduced in pregnancy

LEFt Score = 1

Pre-test Probability: Low (~7%)

Recommended Action:

- Compression ultrasound recommended

- D-dimer has limited utility in this group

- Proceed directly to imaging in most cases

LEFt Score ≥ 2

Pre-test Probability: High (~25-30%)

Recommended Action:

- Proceed directly to compression ultrasound

- Do not use D-dimer (poor test characteristics)

- Consider empiric LMWH while awaiting imaging if significant delay

🚨 ED Clinical Pathway for Suspected DVT in Pregnancy

• Original Derivation/Validation Study: Chan WS, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(11):765-773. The LEFt rule was derived from 194 pregnant women with suspected DVT and validated in a separate cohort.

• Clinical Performance: In validation, the LEFt score had a sensitivity of 100% (95% CI 87-100%) and specificity of 60% (95% CI 52-68%) for DVT when using a cutoff of ≥1 point.

• Comparison to Wells Score: The Wells Score performs poorly in pregnancy (specificity ~10-20% vs. 60% for LEFt). LEFt is the preferred tool for this population.

• Postpartum Applicability: The rule is validated for use up to 6 weeks postpartum.

◾️Treatment During Pregnancy

- Anticoagulation is the mainstay: LMWH preferred (doesn’t cross the placenta)

- Avoid warfarin (teratogenic) and DOACs (safety not established)

- Duration: At least 3 months total, covering the remainder of pregnancy + 6 weeks postpartum

- Delivery planning: Hold LMWH 24h before delivery if possible; avoid neuraxial anesthesia within 24h of dose

◾️High-Risk Situations

- Life-threatening PE: Consider thrombolysis (systemic or catheter-directed)

- Contraindication to anticoagulation: Temporary IVC filter (suprarenal placement)

- Massive DVT: Catheter-directed thrombolysis/thrombectomy for phlegmasia

◾️Postpartum Management

- LMWH or warfarin is acceptable while breastfeeding

- DOACs are avoided during lactation

- Key risk period: First 6 weeks postpartum

◾️Special Considerations

- Bleeding risk assessment must include obstetric-specific risks: placental abruption, postpartum hemorrhage

- Multidisciplinary team essential: MFM, hematology, anesthesia, neonatology

- IVC filter radiation risk to fetus minimal (~2 mGy; threshold for harm >50 mGy)

MEDIA

Going further

References

Gutentor Simple Text

Add comment