4 December 2025 by Shahriar Lahouti.

CONTENTS

- Preface

- Epidemiology and Risk Factors

- Clinical presentation of PE

- Differential diagnosis

- Diagnostic evaluation

- D-dimer

- DVT Ultrasound for PE evaluation

- CTPA

- Diagnostic performance

- 📊Terminology

- Clot location vs. risk. stratification

- Diagnosis of Acute PE

- Applied anatomy

- Key radiologic findings

- Exclusion clues for acute PE

- Mimics of acute PE on CTPA

- Ventilation/Perfusion (V/Q) Scan

- Diagnosing PE

- Managing PE

- Appendix

- References

Preface

The emergency department is the critical junction for diagnosing pulmonary embolism (PE), where decisions carry immediate and significant consequences. While timely treatment is paramount, the reflexive rush to CT imaging and anticoagulation can lead to over-testing, over-diagnosis, and patient harm. This guide synthesizes a modern, evidence-based approach to PE, moving beyond simple “rule-in/rule-out” algorithms. It focuses on the nuanced evaluation of clinical probability, the intelligent application and limitations of D-dimer, and the strategic use of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) to streamline care. Central to this discussion is the management of low-risk and subsegmental PE, where a “less is more” philosophy—emphasizing risk stratification, shared decision-making, and selective outpatient management—can optimize outcomes while minimizing iatrogenic risk. This is a practical framework for balancing diagnostic vigilance with thoughtful resource utilization in the evaluation of suspected PE.

Epidemiology

◾️Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a major public health problem, affecting more than half a million patients annually in the United States.

◾️Pulmonary embolism remains particularly concerning as it is the third leading cause of cardiovascular death, underscoring why emergency clinicians must remain vigilant for this diagnosis.

◾️VTE encompasses both PE and DVT, with DVT accounting for roughly 75% of cases and PE for the remaining 25%.

- Importantly, these entities are not isolated. Approximately 40% of patients with DVT also harbor a PE, while up to 70% of patients diagnosed with PE have evidence of DVT. Here are the primary reasons for the discrepancy between rates of PE and DVT:

- Complete Embolization of the Source Clot

- Mechanism: The entire thrombus detaches from its origin (often a proximal DVT) and travels to the lungs, leaving no residual clot in the deep veins *.

- Clinical Implication: This is more common with mobile, fresh thrombi that are loosely attached. Pelvic/iliofemoral DVTs are particularly prone to this.

- In Situ Thrombosis (less common but important) *

- Other mimics of PE on CTPA without a peripheral venous source of thrombosis, e.g., tumor emboli, septic emboli from right-sided infective endocarditis, or thrombophlebitis.

- Pathophysiological factor

- Hypercoagulable states (e.g., cancer): Some malignancies (especially pancreatic, lung, ovarian) are associated with a high rate of isolated PE without DVT, possibly due to a combination of systemic hypercoagulability and direct vascular injury *.

- Anatomical sources missed by standard imaging

- Standard diagnostic workup for DVT typically involves compression ultrasound of the lower extremities. This misses several potential thrombus sources mentioned in the following table.

- Complete Embolization of the Source Clot

| Source Location | Why It’s Missed |

|---|---|

| Pelvic Veins (Iliac) | Not well visualized on standard leg ultrasound. Requires CT/MR venography. |

| Inferior Vena Cava (IVC) | Requires dedicated imaging (CT, MRI, echocardiography). |

| Right Heart Chambers (atrial fibrillation, heart failure, catheter-induced) | Requires echocardiography. |

| Upper Extremity DVT | Not routinely scanned unless specifically suspected. |

| Renal or Hepatic Veins | Requires abdominal CT/MR venography. |

Why is DVT absent in ~30% of PE cases? This occurs due to complete embolization of the source clot, limitations of imaging, and anatomical sources that are difficult to visualize. The absence of DVT does NOT rule out PE in a symptomatic patient.

Risk Factors

◾️Why Risk Factors Matter

- Because the clinical presentation of PE and DVT is highly variable and often overlaps with other common ED conditions, these diagnoses frequently remain on the differential for patients with chest pain, dyspnea, syncope, hypoxemia, or leg swelling.

- In fact, up to 1 in 10 emergency department patients undergo evaluation for possible VTE.

- This wide net reflects both the nonspecific nature of symptoms and the serious consequences of a missed diagnosis, underscoring why clinicians must be knowledgeable and deliberate in assessing risk factors that influence pretest probability.

◾️Risk Factors: Clinical Relevance in the ED

- Risk factor tables are useful, but not every epidemiologic risk factor translates into a higher diagnostic yield in the ED.

- Pregnancy and travel are good examples: both increase the population risk of VTE, yet their predictive value in the ED is low because clinicians already maintain a very low threshold to test these groups.

- At the same time, many patients with PE have no obvious clinical risk factors at presentation, making it essential to consider both classic and occult contributors when evaluating suspected VTE.

- Pregnancy

- ~5× higher risk of VTE vs. nonpregnant women.

- While VTE risk seems similar across pregnancy trimesters, the data aren’t entirely consistent. What’s clear is that risk peaks in the postpartum period.

- Only 4% of pregnant women tested in the ED are diagnosed, vs. 12% of nonpregnant patients.

- This reflects a deliberately low threshold for testing.

- ~5× higher risk of VTE vs. nonpregnant women.

- Travel

- Prolonged travel modestly increases absolute risk.

- Despite that in the ED a history of travel frequently prompts evaluation, the diagnostic yield is low.

- No apparent risk factors

- Up to 50% of PE patients present without identifiable risks.

- Absence of known risk factors does not exclude VTE.

- Occult risk factors

- Cancer: 4–11% of patients with VTE are diagnosed with malignancy within 1 year.

- Thrombophilia: genetic/acquired states are often unrecognized until the first event.

- HIT: Paradoxical hypercoagulability following heparin exposure.

- Pregnancy

Individual risk factors (e.g., pregnancy, travel) may shift probability, but the decision to test for PE should always be guided by the overall pretest probability — in other words, the entire clinical picture: symptoms, signs, and risk factors together, not by any single risk factor in isolation.

⚠️Risk Factor

| Risk Category | Risk Factors |

|---|---|

| High Risk (OR > 10) |

• Orthopedic: Hip/knee fracture, or replacement.1 • Surgery/Trauma: Major general surgery, major trauma, spinal cord injury with paralysis.1 • Prior VTE (DVT/PE).1 • Cardiac disease: CHF/AF hospitalization within 3 months, recent MI.2 • Homozygous Factor V Leiden mutation.4 |

| Moderate Risk (OR 2–10) |

• Age >80 years old.1 • Central venous catheter/pacemaker leads.7 • Arthroscopic knee surgery.1 • Paralytic stroke.3 OB&Gyn: • Estrogen contraceptives.5 • HRT (estrogen).2 • Postpartum (esp. C-section).5 • IVF.2 • Active cancer (lung, pancreas, gastric, kidney, prostate, brain, hematologic).1, 7 • Congestive heart failure.2 • Respiratory failure (e.g., COPD).3 • Familial protein C/S/antithrombin deficiency.3 • Heterozygous Factor V Leiden mutation.4 • Inflammatory bowel disease.3 • Autoimmune disease.3 • HIT (untreated).1 • Infection (pneumonia, UTI, HIV).7 • Superficial vein thrombosis.2 • Erythropoietin use.7 |

| Low Risk (OR < 2) |

• Pregnancy.5 • Long travel (>6 h).2 • Bed rest >3 days.1 • Varicose veins.3 • Obesity (BMI >35).1 • Smoking.2 • DM.7 • HTN.7 • Older age (<80).1 • Laparoscopic surgery.7 |

References (click to expand)

- Heit JA, et al. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(6):809–815.

- Anderson FA, Spencer FA. Circulation. 2003;107:I-9–I-16.

- Kyrle PA, Eichinger S. Lancet. 2005;365:1163–1174.

- Rosendaal FR. Lancet. 1999;353:1167–1173.

- Lijfering WM, et al. Thromb Haemost. 2009;101:498–503.

- Prandoni P, et al. Haematologica. 2007;92:199–205.

- Kearon C, et al. CHEST Guideline. Chest. 2021;160:e545–e608.

- Konstantinides SV, et al. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:543–603.

- Raskob GE, et al. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:2363–2371.

Diagnostic Considerations

Clinical Presentation of PE

The presentation of pulmonary embolism is highly variable. It may cause cardiovascular symptoms (e.g., syncope, anginal chest pain) and nearly any pulmonary symptom other than purulent sputum production. As such, an exhaustive list of symptoms may be overwhelming rather than clarifying. It is more useful to group them into recognizable clinical patterns.

- In these patients, pulmonary embolism typically presents with cardiovascular manifestations rather than the classic respiratory symptoms. Recognizing these features is crucial, as they often indicate a significant hemodynamic compromise.

-

- Syncope or presyncope.

- Bradycardia.

- Cardiac arrest (PEA or bradyasystolic arrest).

- Substernal anginal chest pain may reflect ischemia of the right ventricular myocardium.

- Diaphoresis and ashen/grey appearance are caused by an outpouring of endogenous catecholamines (epinephrine surge).

◾️Initial Imaging Findings

- Early diagnostic studies are often nonspecific but can provide important clues:

- POCUS → Right ventricular dilation is common.

- A chest radiograph is typically normal, since emboli are located in central pulmonary arteries.

- Pleural effusion is an uncommon finding.

Pulmonary embolism can present primarily with cardiovascular collapse (syncope, bradycardia, or cardiac arrest) rather than respiratory complaints. Always keep PE on the differential in unexplained circulatory shock or PEA arrest.

◾️Respiratory-Dominant Presentations of PE

- Pulmonary embolism presents with acute respiratory complaints, which remain the most common and recognizable clinical pattern. These features should always raise suspicion in the appropriate context.

- Sudden onset of dyspnea at rest or with exertion *

- Hypoxemia

◾️Initial Imaging Findings

- Basic chest imaging is often nondiagnostic but may provide supportive clues:

- Chest radiograph → frequently normal, as emboli reside in the central pulmonary vasculature

- Pleural effusion → present in ~25% of cases

A normal chest radiograph in a patient with acute dyspnea and hypoxemia should heighten suspicion for PE, since thrombi typically reside in the central pulmonary vasculature.

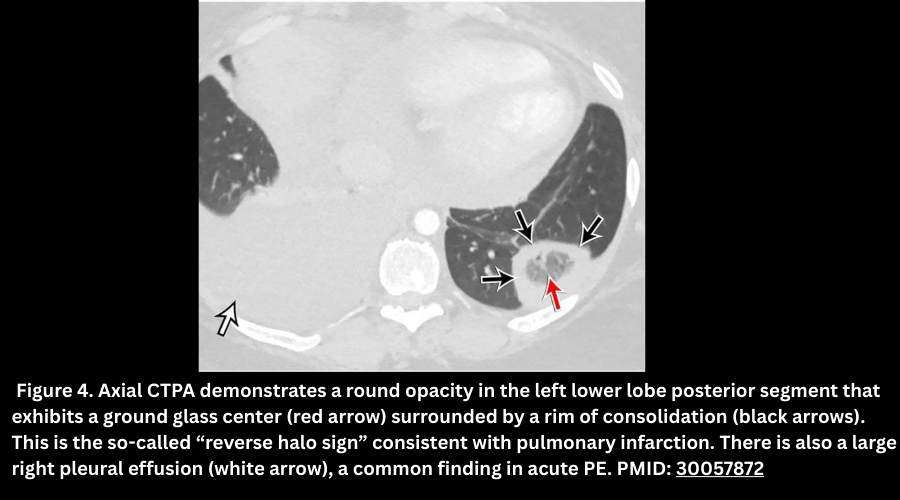

◾️Pulmonary infarction occurs when emboli reach the distal pulmonary arteries, producing vascular obstruction and focal lung necrosis.

- It often reflects smaller emboli, either isolated peripheral PEs or fragments from a larger clot.

- While rarely immediately life-threatening, infarction is common, seen in roughly 15–30% of patients with PE.

◾️Key Symptoms

- Hemoptysis is due to capillary oozing, typically mild and not massive.

- Clinical Pearl: Mild hemoptysis in PE is not a contraindication to anticoagulation.

- Pleuritic chest pain is caused by pleural irritation.

- Low-grade fever, usually <37.7 °C; rarely >39.4 °C.

- Isolated dyspnea can occasionally be the sole presenting feature.

◾️Imaging Features of pulmonary infarction

- Anatomic distribution

- Classically, a pleural-based wedge-shaped opacity.

- However, it may involve the fissure or mediastinal pleura (so it may not always be wedge-shaped).

- Typically, in the lower lobes, multiple lesions may mimic multinodular disease.

- Classically, a pleural-based wedge-shaped opacity.

- CT findings

- Consolidation (necrotic tissue).

- Ground-glass opacities (local hemorrhage).

- Reverse halo sign (rim of consolidation with central ground-glass).

- Cavitation (rare).

- Evolution: Over 3–5 weeks, infarcts shrink while remaining homogeneous → “melting ice cube sign.”

- Pleural effusion accompanying pulmonary infarction

- Pleural effusion is present in ~60% of cases.

- Ipsilateral to the infarct.

- Often subtle (e.g., mild costophrenic blunting).

Hemoptysis in the context of pulmonary embolism is usually mild and not life-threatening, resulting from capillary oozing in necrotic lung tissue. Importantly, this is not a contraindication to anticoagulation when PE is confirmed.

◾️DVT may present as an isolated condition or in association with pulmonary embolism. Recognition is important, though clinical findings are often nonspecific.

- ~50% of DVTs are clinically silent.

- Pain is the most frequent complaint.

- Patients may report only mild cramping or a sense of fullness in the calf.

- Other symptoms may include swelling and redness.

◾️Signs of extremity DVT

- Unilateral edema or swelling with a difference in calf or thigh circumferences

- Localized tenderness along the vein (tender cords).

- Asymmetric pitting edema of the limb.

- Skin discoloration (erythema or cyanosis).

- Dilated superficial veins.

- Increased limb warmth.

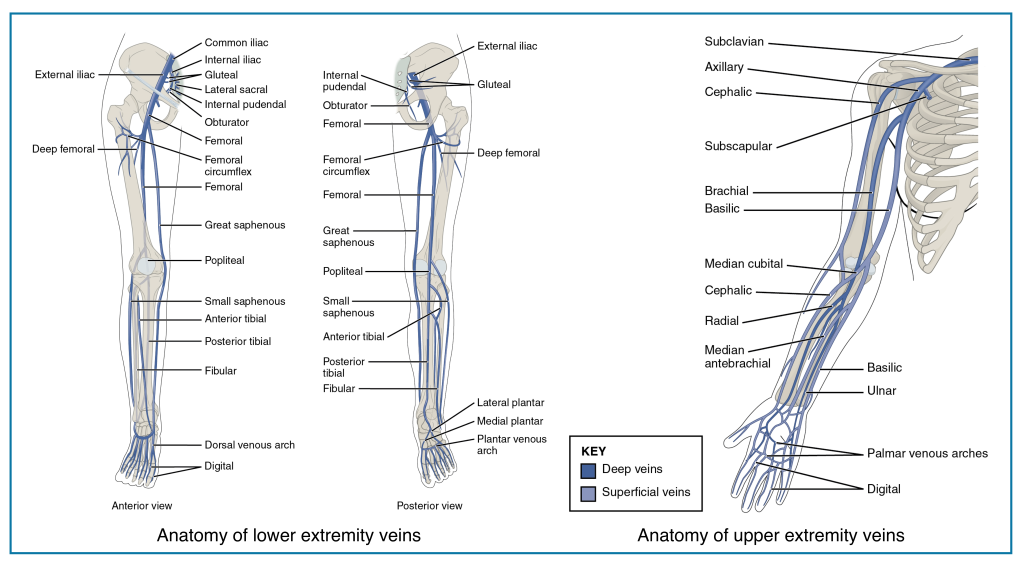

◾️Diagnosis of DVT here

- The probability that a DVT will cause a PE depends significantly on the location of the thrombus.

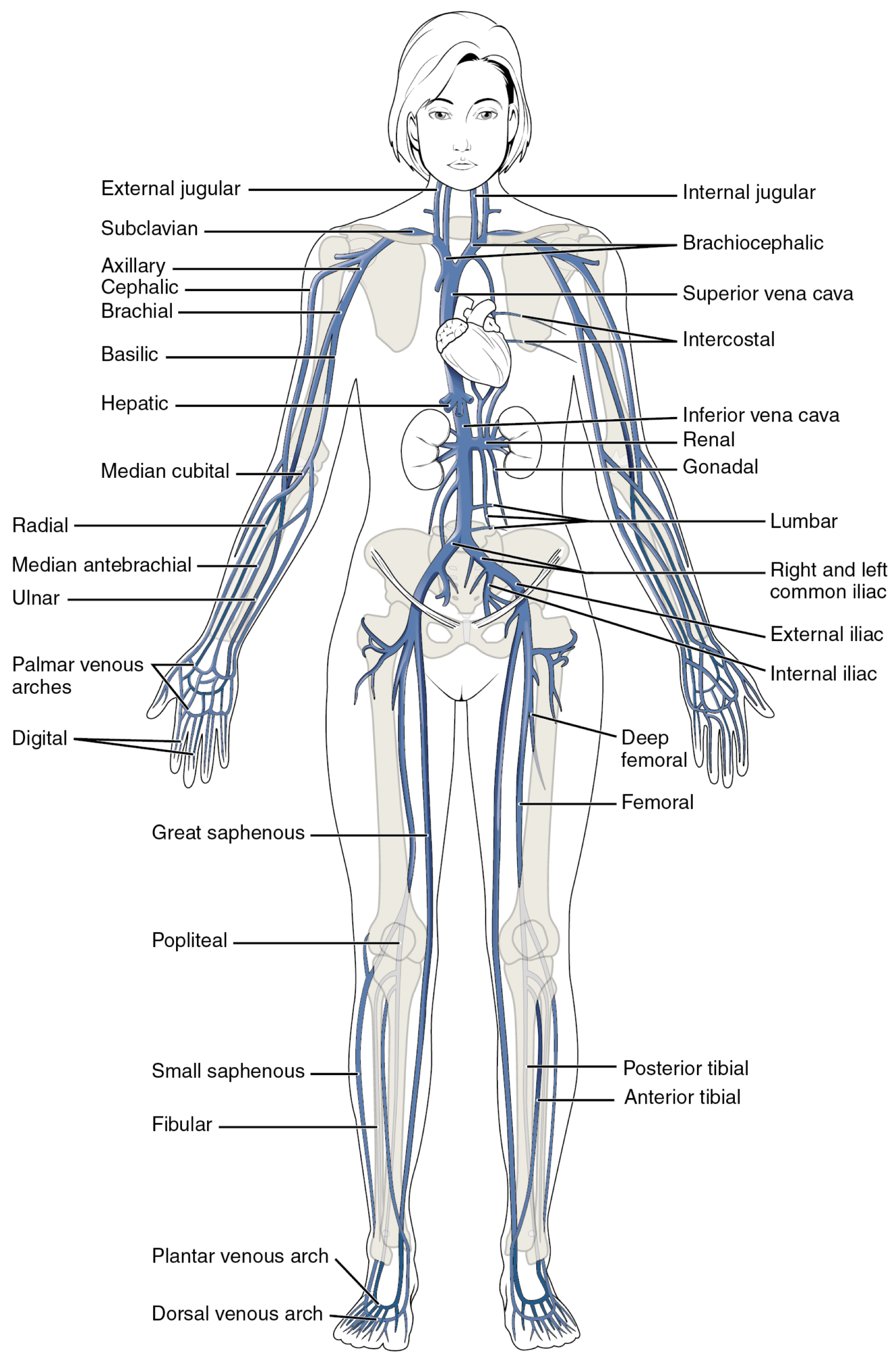

- The anatomy of the extremities’ veins is shown in the figures below.

- 👉Distal greater saphenous vein thrombi are often referred to as superficial thrombosis, but greater saphenous clots near the connection with the femoral vein should be referred to as DVT.

- ⚠️ Pelvic veins are large-caliber vessels, and a thrombus that forms here or propagates into them has a significant volume and can easily embolize into the lung, causing massive PE.

- ⚠️Proximal DVTs have a higher risk of PE compared to distal DVTs, while clots in certain unusual locations, like mesenteric veins, carry a different risk profile and are often related to underlying conditions like cancer.

- Lower extremity DVT (LEDVT) accounts for ~ 90% of total cases of DVT.

- Proximal DVT: In the deep veins at or above the knee.

- Specific veins: Popliteal, femoral, common femoral.

- The femoral vein (previously known as the superficial femoral vein) is joined by the deep femoral vein and then the greater saphenous vein to form the common femoral vein, which subsequently becomes the external iliac vein at the inguinal ligament *.

- Venous thrombi in the proximal femoral and iliac veins are known as iliofemoral DVT.

- This carries a significant risk of PE and requires aggressive anticoagulation.

- Specific veins: Popliteal, femoral, common femoral.

- Distal DVT (Isolated distal DVT or calf vein DVT): In the deep veins below the knee.

- Specific veins: Peroneal, posterior tibial, anterior tibial, and gastrocnemius (Soleal) veins.

- This carries a lower risk of embolization. However, if untreated, some portion of these clots can propagate into the proximal veins and significantly increase PE risk.

- Proximal DVT: In the deep veins at or above the knee.

- Pelvic DVT. This is a crucial location as the clots are often large and carry a high risk of massive PE.

- Pelvic veins: Iliac veins, including the common, external, and internal iliac veins. Other pelvic veins are ovarian (can be associated with pregnancy or postpartum), uterine, prostate, bladder, and pudendal veins.

- ⚠️Risk for PE: Pelvic veins are large vessels, so thrombi here are high-volume and can easily embolize, causing large, life-threatening PEs.

- Diagnostic challenge: Pelvic veins are poorly visualized on a standard leg ultrasound. If suspicion remains high despite a negative scan, targeted iliac imaging or CT/MR venography is needed.

- Unique etiology: May–Thurner syndrome is a key anatomical cause of iliac DVT and may require interventions such as thrombolysis or stenting in addition to anticoagulation.

- Upper extremity DVT (UEDVT): These are becoming increasingly recognized, often associated with intravenous catheters and medical devices, accounting for ~3% of total cases of DVT *.

- Associated Conditions:

- Primary UEDVT: Paget-Schroetter Syndrome (also called “effort thrombosis”), which is a thrombosis of the subclavian/axillary vein following strenuous activity.

- Secondary UEDVT: Most common cause is the presence of a Central Venous Catheter (CVC), Pacemaker, or Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator (ICD) wires. Also associated with cancer.

- Location

- Peripheral UEDVT: Veins of the arm

- Specific veins: Brachial, radial, and ulnar veins.

- Central UEDVT: Veins near the torso

- Specific veins: Axillary, subclavian, and brachiocephalic veins.

- Peripheral UEDVT: Veins of the arm

- Associated Conditions:

- Unusual site/Visceral Vein Thrombosis

- Mesenteric vein thrombosis

- Location: Veins draining the intestines.

- Clinical Significance: Can lead to bowel ischemia (lack of blood flow) and infarction (tissue death). Strongly associated with intra-abdominal cancers (e.g., pancreatic cancer), infection, and inflammatory conditions.

- Portal vein thrombosis

- Location: The main vein carrying blood to the liver from the intestines.

- Clinical Significance: A common cause of portal hypertension. Often seen in patients with liver cirrhosis, abdominal cancer, or infection.

- Splanchnic Vein Thrombosis

- This is an umbrella term for thrombosis in the portal, mesenteric, splenic, and hepatic veins. It is a hallmark of Myeloproliferative Neoplasms (e.g., Polycythemia Vera).

- Renal vein thrombosis

- Location: Veins draining the kidneys.

- Clinical Significance: Can cause kidney injury and is associated with Nephrotic Syndrome.

- Cerebral vein thrombosis

- Location: The Dural venous sinuses in the brain.

- Clinical Significance: A rare but serious cause of stroke, often presenting with headache, seizures, and focal neurological deficits. It is not typically classified as a “DVT” in common parlance, but it is a form of thrombosis in a deep vein.

- Mesenteric vein thrombosis

| DVT Location | Category | PE Risk | Common Symptoms | Clinical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distal (Calf) Posterior Tibial, Peroneal, Soleal |

Lower Extremity | Low to Moderate ~10-20% extend to proximal veins |

• Often asymptomatic • Calf pain/tenderness • Localized swelling • Discomfort on dorsiflexion |

“Isolated Distal DVT” Management controversial: anticoagulation vs. monitoring in low-risk patients |

| Proximal (Femoral, Popliteal) | Lower Extremity | High Most common source of significant PE |

• Unilateral leg swelling • Pain along deep vein tract • Warmth and erythema • Dilated superficial veins |

Standard “DVT” for treatment Requires therapeutic anticoagulation |

| Iliofemoral & Pelvic Iliac, Femoral |

Lower Extremity/Pelvic | Very High Large clot burden → risk of massive PE |

• Massive whole-leg swelling • Groin/thigh pain • Cyanosis (bluish) • Phlegmasia cerulea dolens (emergency) |

Associated with May-Thurner Syndrome May require CT/MR venography |

| Upper Extremity Subclavian, Axillary, Brachial |

Upper Extremity | Moderate PE in up to 1/3 of cases |

• Unilateral arm swelling • Arm/neck/shoulder pain • Dilated chest veins • Cyanosis or heaviness |

Often catheter- or cancer-related Primary: Paget-Schroetter (effort thrombosis) |

| Visceral Mesenteric, Portal, Renal |

Unusual Site | Variable Risk relates to underlying hypercoagulability |

• Not typical DVT signs • Mesenteric: severe abdominal pain, nausea • Portal: abdominal pain, ascites • Renal: flank pain, hematuria |

Red flag for occult cancer Often incidental finding on imaging |

PE Risk Correlates with Clot Burden: The general rule is that more proximal clots in larger veins present a higher risk for PE. A pelvic/iliofemoral DVT is the most dangerous common type.

Symptoms Can Be Misleading: Up to 50% of DVTs can be asymptomatic. Conversely, classic signs like unilateral swelling are not universally present. The absence of symptoms does not rule out a DVT, and the presence of symptoms does not confirm it (other conditions like cellulitis can mimic DVT).

Clinical Decision Rules: The Wells Criteria for DVT is a validated tool used to estimate the pre-test probability of a DVT, which then guides the use of D-dimer testing and ultrasound.

Differential diagnosis of PE

◾️The differential diagnosis of PE encompasses all thoracic conditions that can present with chest pain, dyspnea, or presyncope, including:

- Pneumonia: The most common alternative diagnosis among the ED patients evaluated for possible PE,

- Acute coronary syndromes.

- Aortic dissection.

- Pericarditis.

- Pleural or pericardial effusion.

- Pulmonary hypertension.

- Pneumothorax.

- Acute decompensated congestive heart failure.

- Asthma.

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

- Gastroesophageal reflux, dyspepsia.

- Musculoskeletal pain and nonspecific chest pain.

Most alternative diagnoses can be excluded with a focused bedside workup:

- History & physical examination

- Chest radiograph

- EKG ± cardiac troponin

- Cardiopulmonary POCUS

Diagnostic Evaluation

1. D-dimer

The D-dimer assay is a widely used test in the evaluation of suspected venous thromboembolism. Its major strength lies in its high sensitivity, but its interpretation is limited by low specificity, especially in hospitalized or critically ill patients. Understanding its cutoffs, units, and adjustments is essential for safe and effective use in the ED.

Sensitivity

- Very sensitive for acute PE/DVT (~98%).

- Causes for false-negative D-dimer results are summarized in the following table.

- For example, levels decline over time after the initial event → patients presenting >2 weeks after acute PE/DVT may have a false-negative.

Etiology of False Negative D-Dimer Results

Understanding why venous thromboembolism (VTE) may be present despite a D-dimer level below the diagnostic cutoff

| Category | Specific Etiologies & Mechanisms | Clinical Context & Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Test-Related & Timing Issues |

• Testing too early: Insufficient fibrin cross-linking and degradation at symptom onset. • Testing too late: Low fibrinolytic activity in chronic, organized thrombus. • Assay limitation: No assay has 100% analytical sensitivity (rare). |

• Most relevant for very early symptoms (<24 hours). • Suspected chronic/subacute VTE or CTEPH. • Reinforces need for clinical correlation over lab value alone. |

| Patient-Related Factors |

• Small thrombus burden: e.g., isolated distal DVT or subsegmental PE. • Inadequate fibrinolytic response: Individual biological variation. • Concurrent therapeutic anticoagulation1,2: Unfractionated Heparin LMWH DOACs Warfarin Suppresses D-dimer generation/release. |

• D-dimer is NOT reliable to rule out VTE in patients on therapeutic anticoagulation. • Effect seen with all anticoagulant classes1,2. • Explains false negatives in “low-volume” VTE. |

| Thrombus Characteristics |

• Chronic, organized clot: Minimal fibrin turnover (e.g., in CTEPH). • Non-fibrin thrombus: Tumor emboli, septic emboli, or foreign material. |

• Critical when suspicion is high for alternative clot types. • Particularly important in chronic thromboembolic disease. • The test detects fibrin breakdown; non-fibrin material won’t trigger it. |

- 1Righini M, et al. Effect of anticoagulation on the D-dimer level in patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. Thromb Haemost. 2008;99(5):889-894. Key finding: Patients on therapeutic anticoagulation at time of D-dimer testing had significantly lower D-dimer levels, increasing risk of false negatives.

- 2Kline JA, et al. D-dimer concentrations in normal pregnancy and in pregnancy complicated by thromboembolism: a systematic review. Thromb Res. 2018;162:110-119. Key finding: Anticoagulation therapy reduces D-dimer levels across multiple clinical scenarios, potentially masking VTE diagnosis.

- 3Kearon C, et al. Diagnosis of suspected venous thromboembolism. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2016;2016(1):397-403. Key point: D-dimer should not be used to rule out VTE in patients already receiving therapeutic anticoagulation due to unreliable results.

- 4Di Nisio M, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of D-dimer testing in patients with a history of venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Haemost. 2019;119(6):889-900. Key finding: D-dimer specificity and sensitivity are altered in patients with recent anticoagulation exposure.

- 5van der Hulle T, et al. Recent developments in the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary embolism. J Intern Med. 2016;279(1):16-29. Key point: All anticoagulant classes (heparins, DOACs, warfarin) can suppress D-dimer production, making test interpretation challenging.

- 6Stevens SM, et al. Executive Summary: Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease: Second Update of the CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2021;160(6):2247-2259. Guideline statement: “D-dimer testing should not be used to exclude VTE in patients who are already receiving therapeutic anticoagulation.”

Specificity

- Nonspecific marker. Many conditions elevate D-dimer (Table below) *

- In critically ill patients (e.g., medical ICU without VTE), ~80% have elevated D-dimer → extremely low specificity in this setting.

Etiologies of False Positive D-Dimer Results

Conditions causing elevated D-dimer without venous thromboembolism, with physiologic explanations

| Category | Specific Etiologies & Examples | Physiologic Explanation & Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory |

• Infection: Pneumonia, sepsis, COVID-191 • Autoimmune diseases: SLE, rheumatoid arthritis • Inflammatory states: Pancreatitis, IBD |

• Cytokine-mediated fibrinolytic activation: IL-6, TNF-α stimulate tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) release, increasing fibrin degradation • Endothelial activation/damage: Direct vascular injury triggers coagulation cascade • NETosis: Neutrophil extracellular traps provide scaffold for fibrin deposition and degradation |

| Hemolytic/Ischemic |

• Hemolytic disorders: Sickle cell crisis, TTP, DIC • Ischemic events: Myocardial infarction, stroke2 • Vaso-occlusive crises |

• Intravascular fibrin formation: Hemolysis releases procoagulant substances (e.g., ADP, hemoglobin) • Thrombotic microangiopathy: Widespread microvascular thrombosis with subsequent fibrinolysis • Tissue ischemia-induced fibrinolysis: Ischemic tissue releases t-PA and other fibrinolytic activators |

| Vascular Pathology |

• Aortic dissection/aneurysm3 • Peripheral artery disease • Vasculitis (e.g., giant cell arteritis) • Venous stasis/insufficiency |

• Intimal injury with mural thrombus formation: Exposed collagen and tissue factor activate coagulation • Stasis-induced thrombosis: Reduced blood flow allows localized fibrin deposition and turnover • Vessel wall inflammation: Inflammatory cells infiltrate vascular wall, activating coagulation locally |

| Neoplastic |

• Solid tumors (especially advanced/metastatic)4 • Hematologic malignancies • Paraneoplastic syndromes |

• Tissue factor expression: Tumor cells express TF, activating extrinsic coagulation pathway • Mucin secretion (adenocarcinomas): Mucins activate factor X • Cytokine production: Tumor-derived IL-1β, TNF-α stimulate endothelial cells to become procoagulant • Direct vascular invasion: Tumor erosion into vessels creates nidus for thrombosis |

| Physiologic/Other |

• Pregnancy (especially 3rd trimester)5 • Postoperative state (first week) • Trauma/surgery • Advanced age (>80 years)6 • Liver disease (cirrhosis) • Renal failure |

• Physiologic hypercoagulability: Pregnancy hormones increase clotting factors; surgery/trauma releases TF • Reduced clearance: Impaired hepatic/renal function decreases D-dimer elimination • Age-related endothelial dysfunction: Increased baseline fibrinolytic activity • Comorbid conditions: Multiple concurrent mechanisms often coexist in elderly |

- 1Wells PS, et al. Application of a diagnostic clinical model for the management of hospitalized patients with suspected deep-vein thrombosis. Thromb Haemost. 1999;81(4):493-7. Key finding: Infection and inflammation significantly increase D-dimer levels independently of VTE.

- 2Di Nisio M, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of D-dimer testing in patients with a history of venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Haemost. 2019;119(6):889-900. Key finding: Acute ischemic events (MI, stroke) elevate D-dimer through tissue factor pathway activation.

- 3Shimony A, et al. D-dimer in acute aortic dissection. Chest. 2013;143(5):1253-1260. Key finding: 95% of aortic dissection patients have elevated D-dimer due to intimal injury and mural thrombus formation.

- 4Khorana AA, et al. Cancer-associated venous thromboembolism. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2022;8(1):1-18. Key finding: Tumor-derived procoagulants and inflammatory cytokines create continuous fibrin formation/degradation cycle.

- 5Kline JA, et al. D-dimer concentrations in normal pregnancy and in pregnancy complicated by thromboembolism: a systematic review. Thromb Res. 2018;162:110-119. Key finding: Progressive D-dimer elevation throughout pregnancy peaks at 3-4× baseline at term due to physiologic hypercoagulability.

- 6Righini M, et al. Age-adjusted D-dimer cutoff levels to rule out pulmonary embolism: the ADJUST-PE study. JAMA. 2014;311(11):1117-1124. Landmark study: Age-adjusted cutoff (age × 10 μg/L for ≥50 years) increases specificity from 34% to 46% in elderly without compromising sensitivity.

- 7Schutgens RE, et al. Use of clinical decision rules in D-dimer testing for venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(6):1225-1228. Key point: Hospitalization itself increases D-dimer by approximately 30% due to inflammatory stress and immobility.

- 8Wada H, et al. Elevated plasma levels of fibrin degradation products by granulocyte-derived elastase in patients with deep vein thrombosis. Thromb Res. 1995;77(2):137-143. Mechanistic insight: Neutrophil elastase directly cleaves fibrin, generating D-dimer independent of plasmin activity.

Units & Cutoffs

- Reported in either:

- FEU (fibrin-equivalent units)

- DDU (D-dimer units)

- Conversion: FEU ≈ 2 × DDU

- Typical cutoffs:

- FEU <500 µg/L (<0.5 µg/mL)

- DDU <230–250 µg/L (<0.23–0.25 µg/mL)

- Knowing the unit matters for age-adjusted and risk-adjusted cutoffs.

| Unit | Conversion | Typical Cutoff | Age-Adjusted Formula |

|---|---|---|---|

| FEU (Fibrin-Equivalent Units) | ≈ 2 × DDU | <500 µg/L (0.5 µg/mL) | Age × 10 (µg/L) |

| DDU (D-dimer Units) | ≈ 0.5 × FEU | <230–250 µg/L (0.23–0.25 µg/mL) | Age × 5 (µg/L) |

🔎 Always confirm whether your lab reports in FEU or DDU before applying cutoffs or age-adjusted formulas.

Age-Adjusted D-dimer

- <50 years: use standard cutoffs (FEU <500 µg/L or DDU <230–250 µg/L).

- ≥50 years:

- FEU cutoff = age × 10

- DDU cutoff = age × 5

- Multiple studies: improves specificity without compromising sensitivity, reducing unnecessary CT scans.

Using an age-adjusted cutoff (age × 10 in FEU, age × 5 in DDU for patients ≥50 years) significantly improves specificity while maintaining sensitivity. This reduces unnecessary CT scans and avoids over-testing in older patients.

Clinical Role

- Negative D-dimer + low/moderate pretest probability = sufficient to exclude PE.

- Low utility in patients with systemic inflammation (e.g., sepsis, shock).

- Practical rule: Only order D-dimer if you are prepared to proceed with CT imaging if positive.

D-dimer is most valuable in patients with low to intermediate pretest probability. A negative result can safely exclude PE, but a positive result is nonspecific and should only be ordered if CT imaging will follow if elevated.

2. DVT Ultrasound in PE evaluation

◾️Sensitivity: Lower extremity ultrasound detects DVT in only ~40% of patients with PE.

◾️Specificity: A positive study is nearly 100% specific for venous thromboembolism, though it does not confirm that PE is present (it may be an isolated DVT).

◾️Clinical utility: Because anticoagulation is the treatment for both DVT and PE, a positive DVT ultrasound often allows clinicians to initiate therapy without CT imaging.

◾️Key caveat: If there is concern for submassive or massive PE requiring advanced interventions (e.g., thrombolysis, thrombectomy), CTPA is still essential to assess clot burden and to distinguish acute PE from chronic pulmonary hypertension.

– A positive DVT ultrasound is nearly 100% specific for venous thromboembolism and often allows clinicians to start anticoagulation without CT imaging.

– However, a negative ultrasound does not rule out PE, since sensitivity is only ~40%. CT pulmonary angiography remains essential if clinical suspicion for PE is high, especially when considering submassive or massive PE.

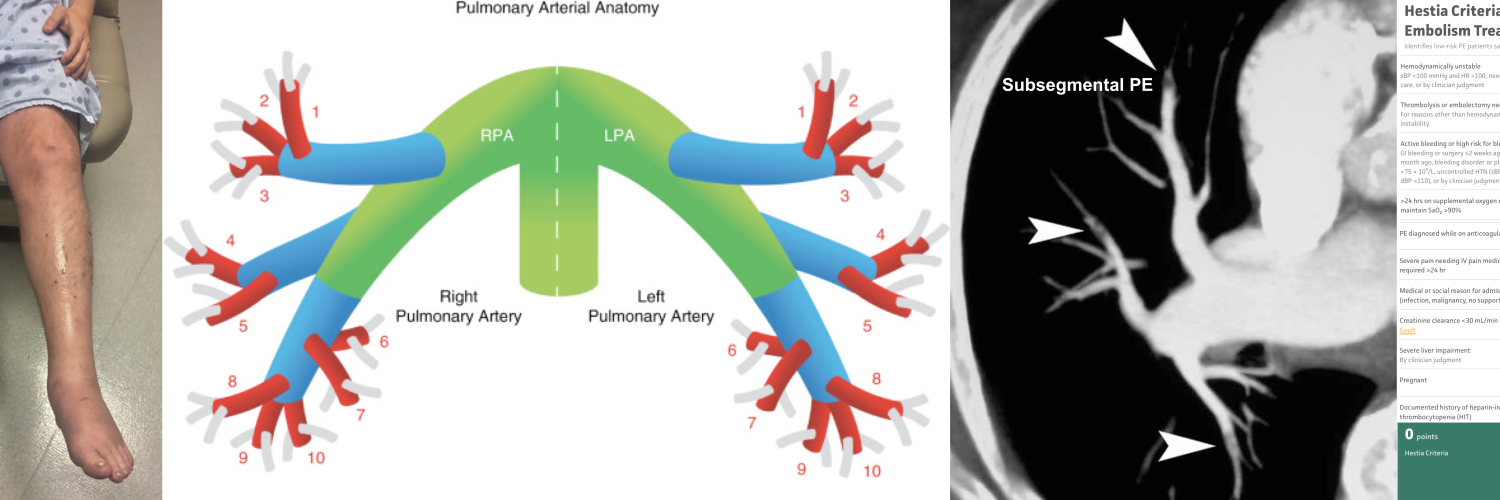

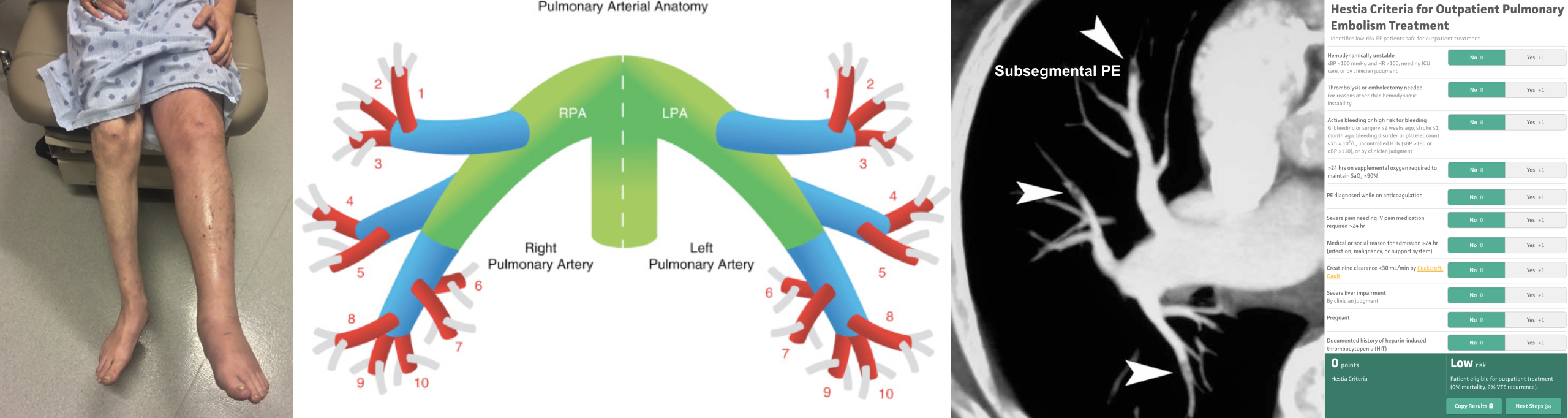

3. CT Pulmonary Angiography (CTPA) for Suspected PE

CT angiography is the first-line imaging modality for pulmonary embolism. Its diagnostic performance depends heavily on the technical quality of the study, so results must always be interpreted in context.

Diagnostic Performance

◾️Sensitivity

- Central and segmental PE: >95% sensitivity.

- Subsegmental PE: lower sensitivity, with more reader variability.

- A modern, high-quality CT is usually sufficient to exclude clinically significant PE.

- Quality check: The main pulmonary artery should enhance to >250 HU *.

- MIP (maximum intensity projection) reconstructions improve visualization of small emboli.

- 💡 Pearl: Always assess study adequacy yourself and, when uncertain, review images with radiology; diagnostic accuracy varies between patients and studies.

◾️Specificity

- High for segmental or larger emboli.

- Lower for isolated subsegmental PE, where inter-observer variability increases the chance of false positives.

- Several mimics of intravascular filling defects can resemble emboli (see below).

| Location of Embolus | CTPA Performance | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Central (main/lobar) | Sensitivity >95% | High-quality scans reliably exclude clinically significant PE |

| Segmental | Sensitivity >95% | Generally accurate with good-quality imaging |

| Subsegmental | Lower sensitivity & specificity | Greater inter-reader variability; may represent false positives |

🔎 Always confirm technical adequacy (e.g., >200 HU in the main pulmonary artery) when interpreting CTPA.

◾️Role in Diagnosis

- CTPA is generally the definitive diagnostic test of choice.

- Concerns about contrast nephropathy have been largely disproven; CTPA should not be withheld solely for renal dysfunction.

- In pregnancy, modern low-dose protocols have made breast radiation negligible (<1/3,000 lifetime cancer risk), so CTPA can be safely performed when clinically indicated.

◾️CT Angiography with CT Venography

- Combines CTPA with pelvic and thigh imaging for DVT detection.

- Uses the same contrast volume but increases radiation exposure.

- Diagnostic yield:

- Comparable to ultrasound for most DVTs.

- It may be superior in obese patients or for proximal iliofemoral thrombosis.

- Best reserved for:

- Older patients (less sensitive to radiation risk).

- Cases where compression ultrasound is impractical (e.g., severe obesity, logistic barriers).

– A modern, high-quality CTPA (>200 HU in the main pulmonary artery) is usually sufficient to exclude clinically significant PE, and radiation/contrast risks are minimal with current protocols.

– ⚠️ Interpretation of isolated subsegmental PE is less reliable, with higher inter-reader variability and potential false positives. Always consider clinical context and discuss uncertain cases with radiology.

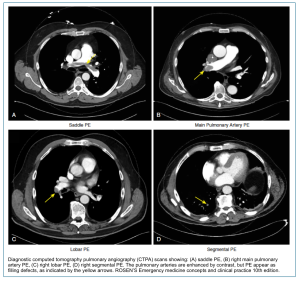

Terminology on CTPA report

| Term | Concise definition (summarized) |

|---|---|

| Acute PE |

Intraluminal filling defect that is central (rounded) or eccentric with acute angles to the vessel wall; the involved artery may be distended. Complete occlusion shows a sharp contrast cutoff with no distal enhancement; partial occlusions often occur at bifurcations. “Railway track” sign: on a longitudinal view, the clot is surrounded by a rim of contrast on both sides, supporting an intraluminal acute thrombus (vs artifact or mural thickening). Practical clues for acute over chronic: acute wall angles, vessel enlargement, and absence of calcified bands/webs; correlate with clinical context. |

| Central PE | Embolus in the pulmonary trunk, main, or lobar pulmonary arteries. |

| Peripheral PE | Embolus in the segmental and/or subsegmental branches (more distal than central PE); thin-slice planes help confirm. |

| Subacute PE | Clot shows lytic change with irregular/concave contours; typical chronic signs absent. |

| Chronic PE | Persistent non-round defects: bands/webs, irregular margins, sometimes calcification; a round cross-section suggests recurrent acute PE instead. |

| Subsegmental PE | Filling defect in a subsegmental artery (first branch distal to a segmental artery), ideally on ≥2 thin axial slices (≤1 mm). |

| Isolated subsegmental PE | Subsegmental PE without proximal emboli (no segmental/lobar/central PE). Verify on thin slices in multiple planes; exclude artifacts and weigh clinical probability. |

| Saddle embolism | Large central clot that straddles the main PA bifurcation. |

| Pulmonary artery filling defect | Area within a PA lacking enhancement while other PAs enhance; causes include embolus, pulmonary thrombosis, or intravascular tumor. |

| In-situ pulmonary thrombus | Wall-adherent defect in large/enlarged PAs (often superior right main PA or intralobar); may have calcification. |

| Pulmonary thrombosis | Thrombi within PAs may arise from VTE or local thrombosis (e.g., PH, COPD, sickle cell, COVID-19). CTA alone cannot reliably distinguish. |

| Reduced PA contrast enhancement (artifact) | Timing/flow or motion issue: attenuation higher than unenhanced blood but lower than fully opacified PA; not a true filling defect. |

| Right ventricular dilatation | Estimate via RV/LV diameters (endocardium→septum) on axial CT; may differ from echo without ECG gating. |

| Right ventricular hypertrophy | RV free-wall thickness > 4 mm. |

| Embolus | Thrombus that has dislodged and lodged downstream from its origin. |

| Thrombus | Intravascular clot that remains at its site of origin. |

| Incidental PE | PE identified on CT performed for reasons other than suspected PE. |

Clot Location and burden vs. Risk Stratification

◾️The treatment of acute PE depends on the risk that the PE poses to the patient. Current risk stratification for acute PE de-emphasizes anatomical clot burden.

- Risk stratification and management decisions are based on clinical, laboratory, and imaging markers of physiological compromise, not the radiographic appearance of the thrombus alone.

◾️Thrombus Location vs. Risk Stratification

- Anatomic Burden is a Marker, Not a Determinant:

- Central (saddle, main/lobar) emboli are associated with a higher likelihood of concomitant right ventricular (RV) dysfunction. However, the hemodynamic impact varies based on cardiopulmonary reserve.

- A patient with a saddle PE may be normotensive, while a patient with smaller, multiple emboli and underlying cardiopulmonary disease may be in shock.

- Thrombus location informs the index of suspicion and may influence decisions about advanced therapies (e.g., catheter-directed thrombolysis) in already intermediate-high or high-risk patients, but it is not an independent criterion for risk class.

- Central (saddle, main/lobar) emboli are associated with a higher likelihood of concomitant right ventricular (RV) dysfunction. However, the hemodynamic impact varies based on cardiopulmonary reserve.

💡Pearls

- Saddle PE: Spans the bifurcation of the main pulmonary arteries. Often large but may be non-occlusive, and patients can be minimally symptomatic.

- Location: Emboli can lodge in main, lobar, segmental, or subsegmental arteries.

- Descriptive Convention: A clot is described by its most proximal location (e.g., a thrombus extending from a lobar into a segmental artery is termed a “lobar PE”).

Diagnosis of acute PE on CTPA

The diagnosis of acute pulmonary embolism (PE) on CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) rests on recognition of a well-defined intraluminal filling defect within the pulmonary arteries. Interpretation requires careful attention to technical quality and multiplanar review to avoid pitfalls *.

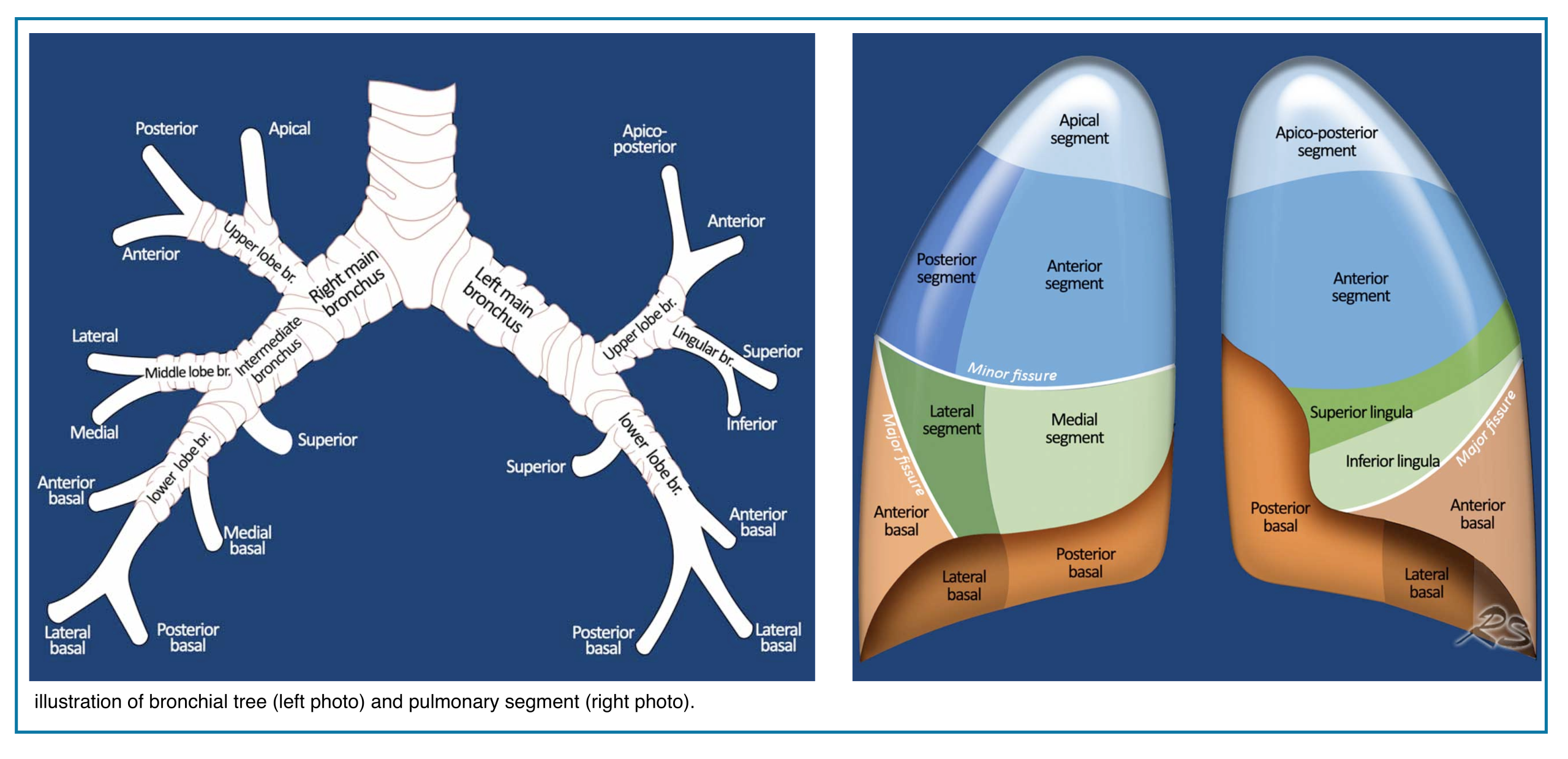

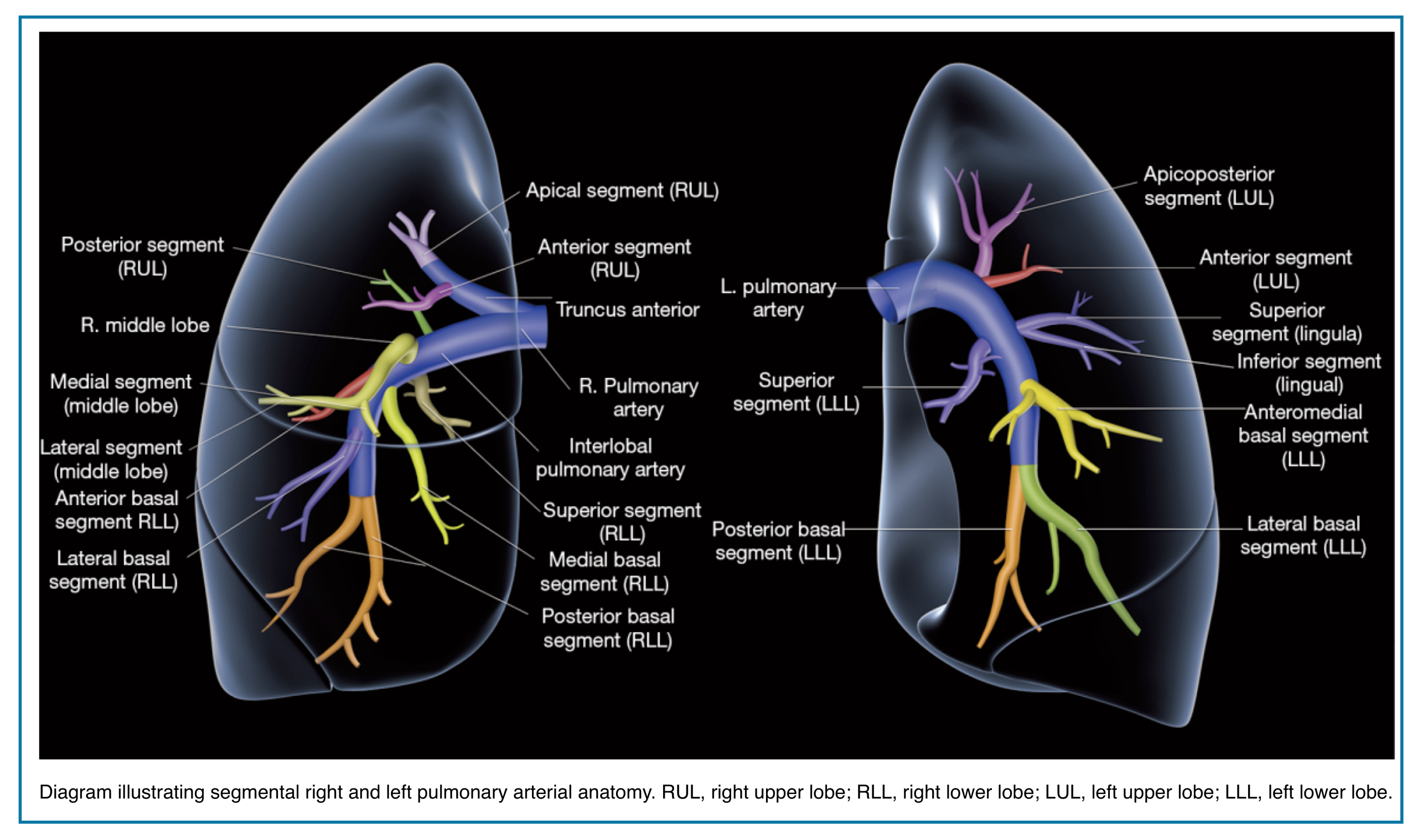

Applied anatomy

- The pulmonary trunk (aka. main pulmonary artery “MPA”) is the sole arterial output from the right ventricle (figure below).

- At the level of the 5th thoracic vertebral body plane, the MPA divides into the right and left pulmonary.

- The right and left pulmonary arteries divide into two lobar branches each, and subsequently into segmental and sub-segmental branches.

-

- Right pulmonary artery

- It gives rise to two branches: the truncus anterior and the interlobar pulmonary arteries.

- Truncus anterior is the 1st branch (ascending) that supplies the right upper lobe.

- The interlobar pulmonary artery runs inferiorly and down the right side, supplying the right middle and lower lobes.

- It gives rise to two branches: the truncus anterior and the interlobar pulmonary arteries.

- Left pulmonary artery

- The left pulmonary artery represents the continuation of the MPA.

- The first lobar branch gives rise to segmental arteries that supply the left upper lobe.

- The interlobar artery gives off divisions to supply the lingula and left lower lobe.

- The left pulmonary artery represents the continuation of the MPA.

- Right pulmonary artery

-

📖 Read more on this Radiology Assistant, Radiopaedia

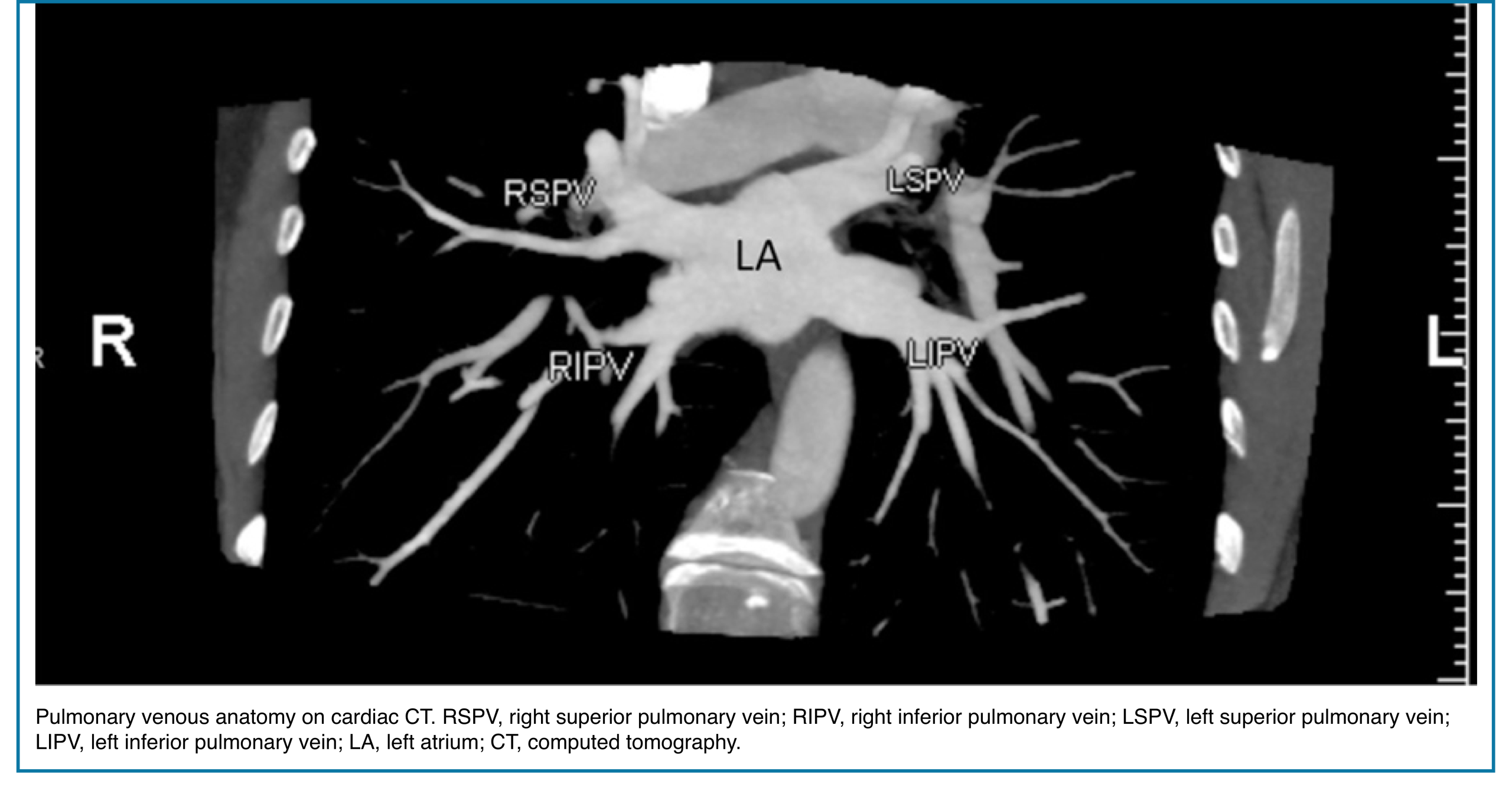

◾️Pulmonary vein anatomy:

- Typically, there are four pulmonary veins with superior and inferior pulmonary veins on either side, draining into the left atrium (Right figure below).

- In both hilae, the superior pulmonary vein is the most anterior structure and the inferior pulmonary vein is the most inferior structure.

- The parenchymal pulmonary vein branches run within interlobular septa and do not parallel the segmental or sub-segmental pulmonary artery branches and bronchi.

💡 Pulmonary Artery Course: Quick Pearl

- Upper lobe arteries run central to their bronchi.

- Middle lobe, lingular, and lower lobe arteries run peripherally to their bronchi.

- Pulmonary veins usually lie anterior to the arteries, except in the right upper lobe, where venous position is more variable.

Key radiological findings of acute PE in CTPA

Direct Radiologic Signs of Clot

A. Clot appearance and characteristics

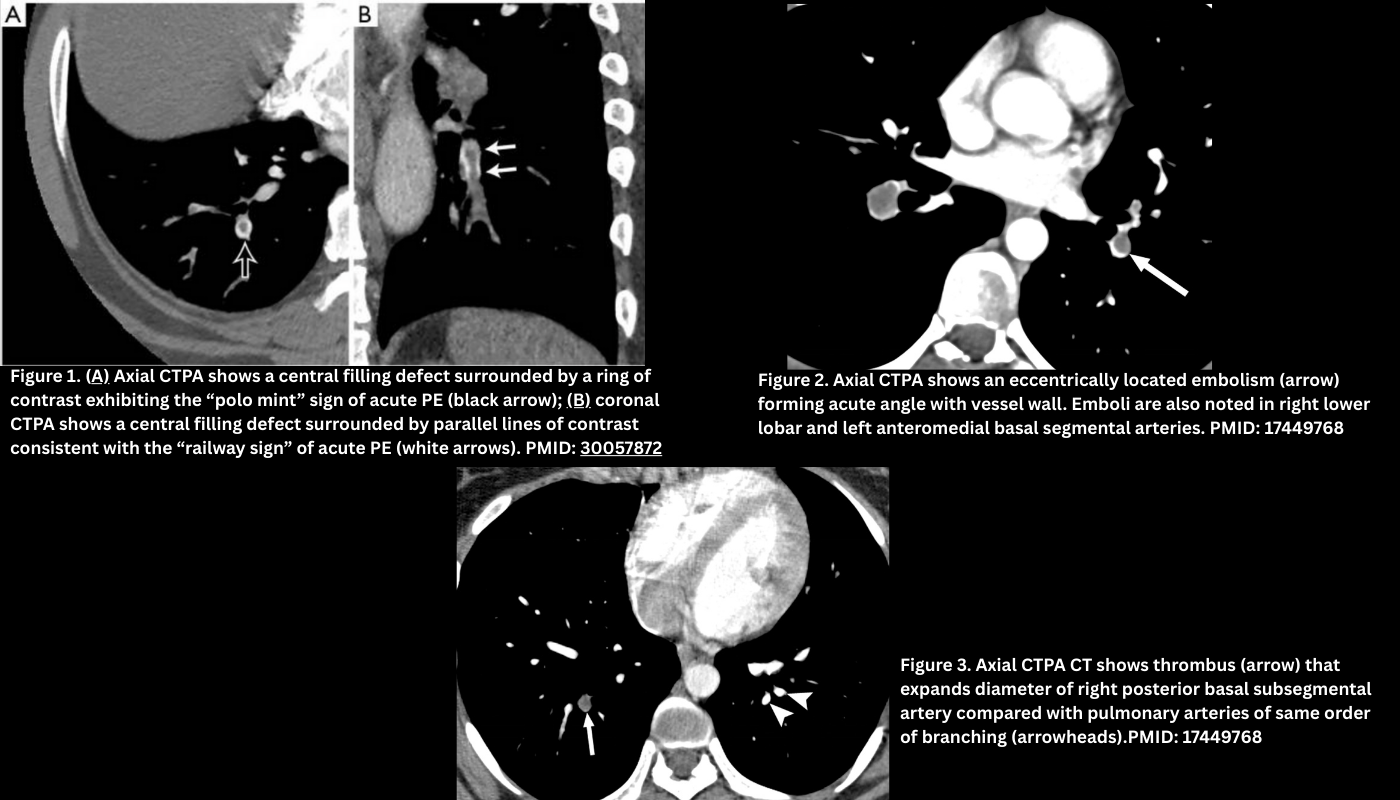

◾️Filling defect

- Appears as a low-attenuation area in a contrast-enhanced pulmonary artery.

- Should be visible in more than one plane and across several slices, with sharp borders to distinguish from flow artifact.

- Filling defects in acute PE may be non-occlusive (i.e., partially occlude the vessel) or occlusive (completely occlude the vessel).

- Non-occlusive filling defects. These filling defects can be located within the center of the involved vessel or, less commonly, adherent to the vessel (eccentric).

- Central. Most filling defects are central within the vessel lumen, surrounded by contrast, producing:

- Polo mint appearance: A central filling defect (the clot) surrounded by a rim of contrast within a circular cross-section of the pulmonary artery → looks like a polo mint in axial CTPA (Figure 1.A).

- Tram-track / railway sign: Endoluminal clot is surrounded by a rim of contrast on both sides (in coronal CTPA). Figure 1. B

- Eccentric (i.e., peripheral filling defects). Less commonly, in acute PE, the clot can be located in contact with the vessel wall. Typically, this clot forms an acute angle with the vessel wall (Figure 2).

- Note that in chronic thromboembolic disease, this angle is obtuse (see below for more information).

- Central. Most filling defects are central within the vessel lumen, surrounded by contrast, producing:

- Occlusive filling defects

- Occlusive PE prevents opacification of the entire lumen and may distend the vessel (Figure 3).

- Note that occlusive defects are nonspecific for acute PE and may occur in chronic thrombosis as well.

- Keep in mind that non-occlusive but flow-limiting PE can also reduce regional pulmonary blood volume.

- Occlusive PE prevents opacification of the entire lumen and may distend the vessel (Figure 3).

- Non-occlusive filling defects. These filling defects can be located within the center of the involved vessel or, less commonly, adherent to the vessel (eccentric).

B. Pulmonary Artery

The pulmonary artery containing an acute PE will be normal in size or expanded, compared to adjacent patent arteries, due to acute distension (Figure 3).

- This is in contrast to the contracted vessels in CTEPD secondary to clot organization and fibrosis.*

C. Lung Parenchyma

- Most often, no parenchymal abnormality is detected.

- May show peripheral wedge-shaped consolidation (infarction) or atelectasis, but these are non-specific acute changes.

- Pulmonary infarcts appear as a peripheral opacity, heterogeneous enhancement, and may show the reverse halo sign (rim consolidation with central ground glass). Figure 4.

- Rarely, the Westermark sign (regional oligemia) is seen.

- Mosaic attenuation is not a typical feature of acute PE alone.

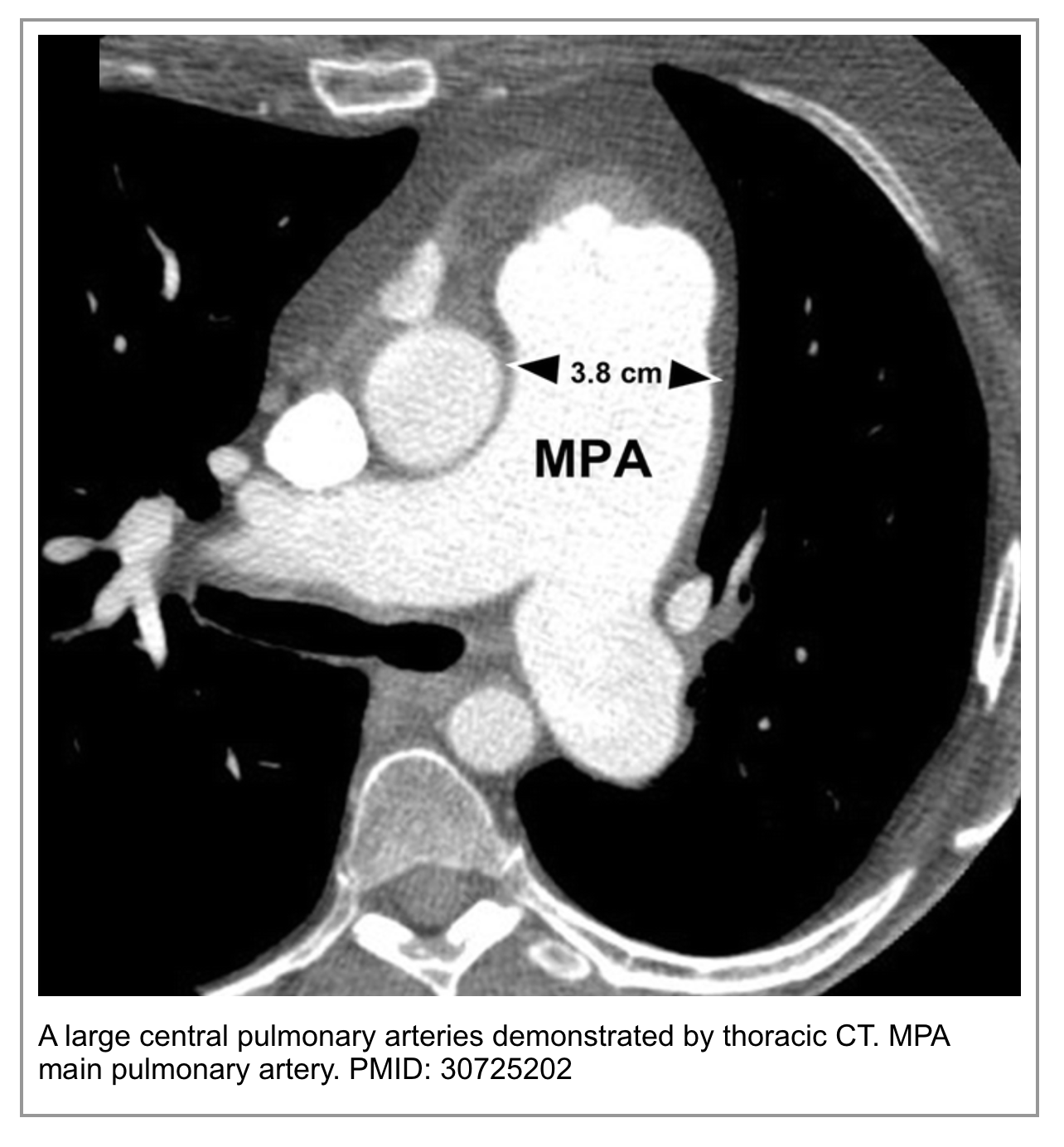

D. Indirect (Physiologic) Features

◾️Main Pulmonary Artery (MPA) Diameter

- The MPA is often normal in size. Acute obstruction does not cause immediate, permanent arterial dilation.

- It may be mildly enlarged due to acute pressure overload, but this is less specific.

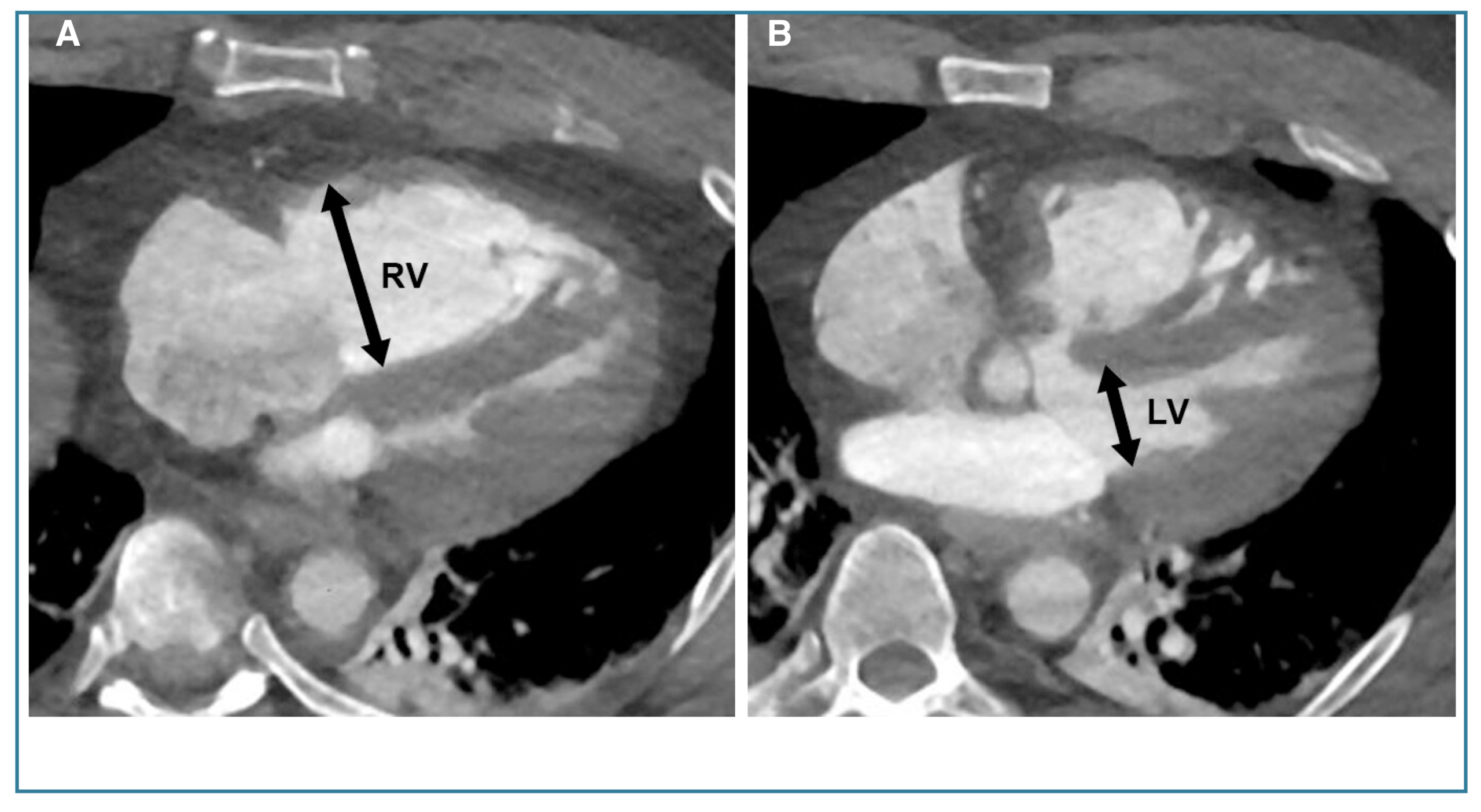

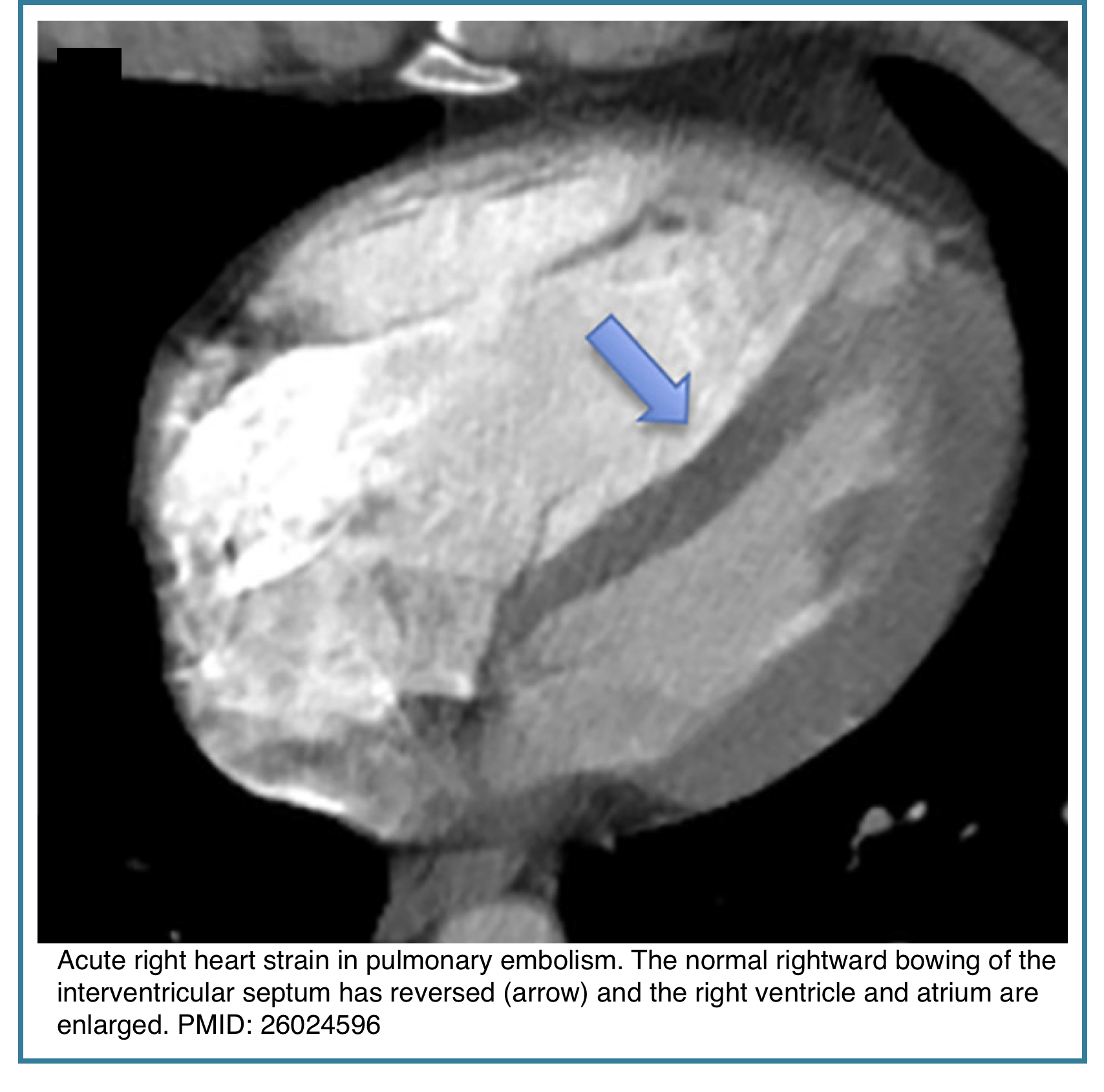

◾️Right Ventricular (RV) Enlargement & Strain

- Acute RV strain/dilatation can and does occur with a large, hemodynamically significant acute PE. It’s a sign of severity.

- Key CT Signs of Acute RV Strain:

- RV/LV Diameter Ratio > 1.0 (measured in the axial plane at the widest point). This is the most commonly used measure.

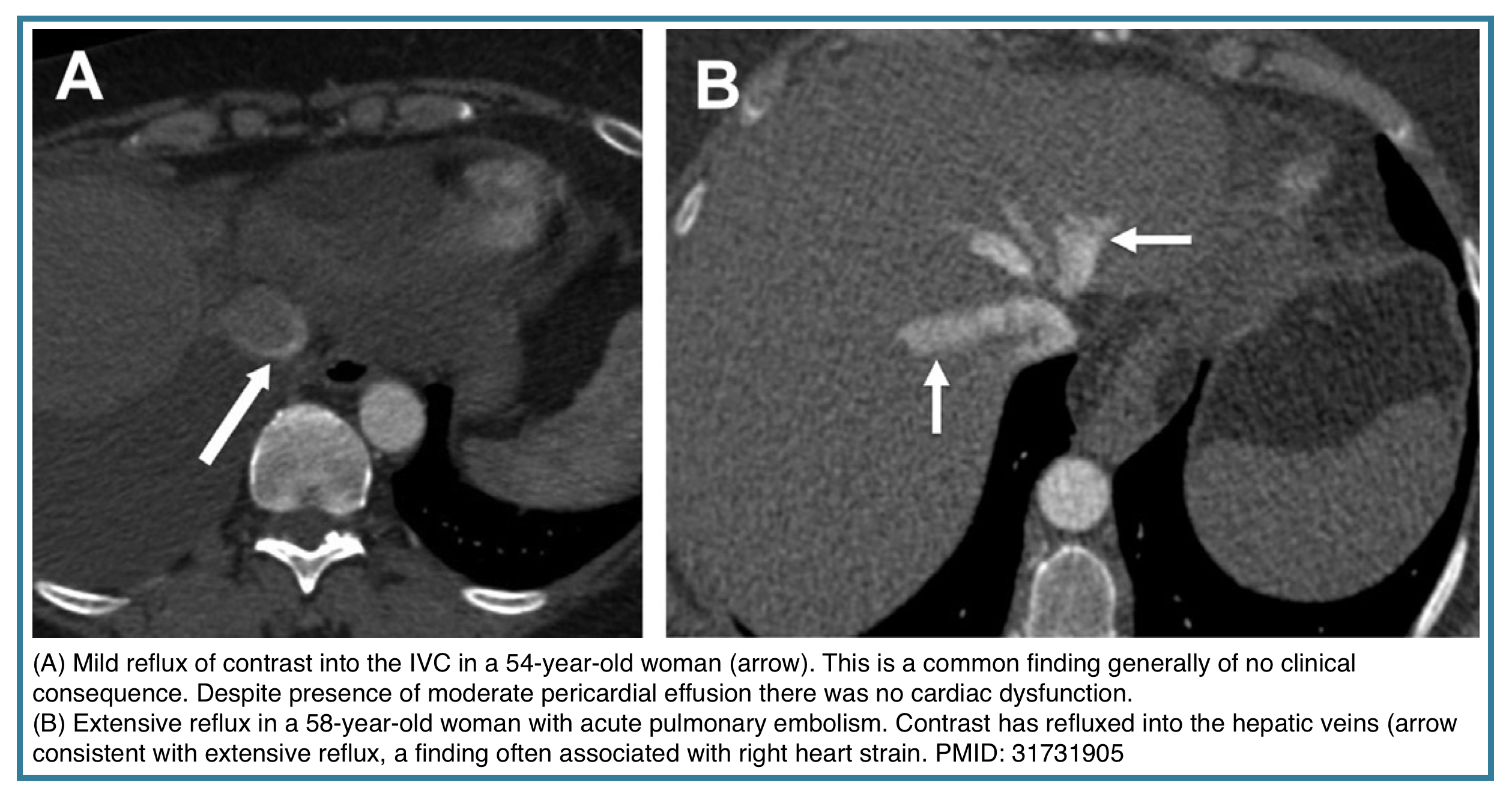

- Septal flattening or bowing into the left ventricle (LV), giving the LV a “D-shaped” appearance.

- Reflux of contrast into the inferior vena cava (IVC) and hepatic veins.

- Crucial Point: In acute PE, this RV enlargement is often disproportionate to the visible clot burden, reflecting acute pressure overload. It can be reversible with treatment.

Exclusion Clues For Acute PE

The presence of certain imaging findings argues against an acute PE as the sole or primary diagnosis. Instead, these findings point to Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Disease (CTEPD) ± an acute-on-chronic event, and include:

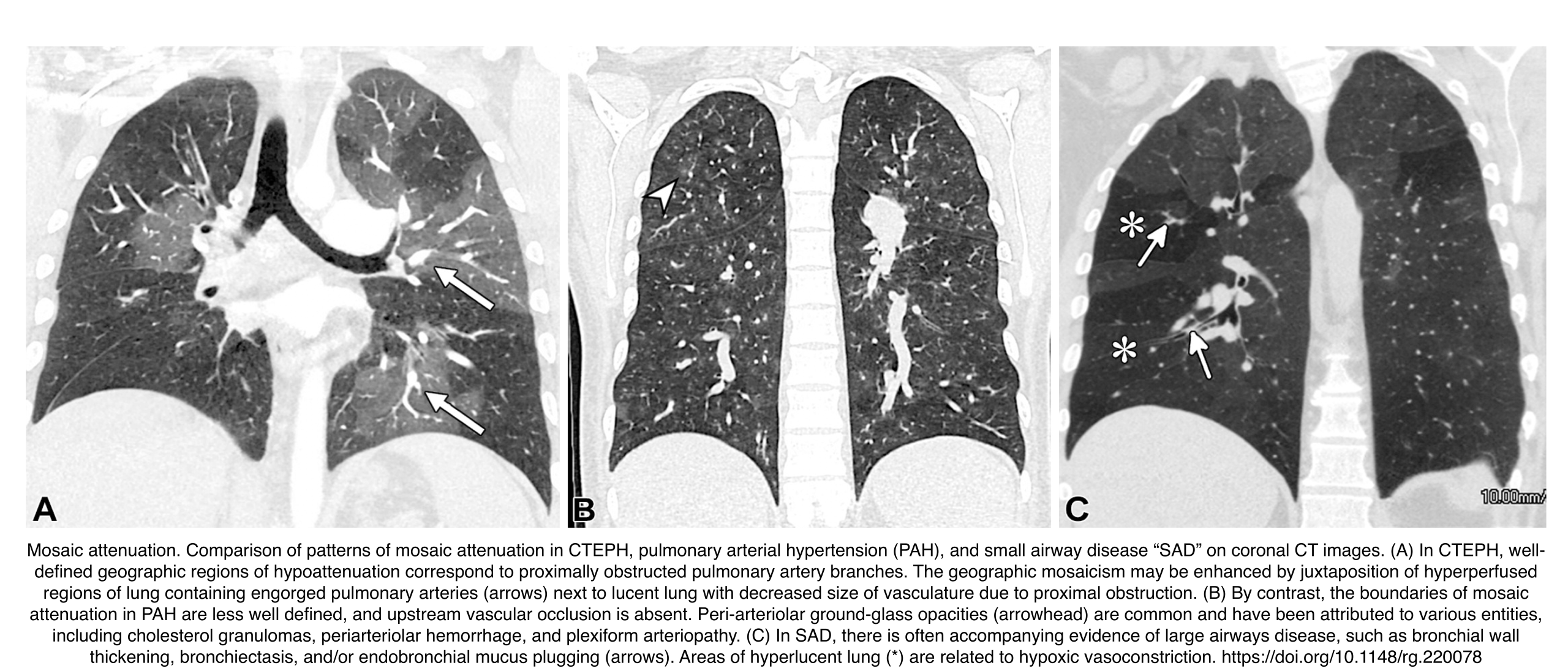

- Mosaic attenuation

- Enlarged bronchial arteries

Mosaic attenuation

Refers to the geographic pattern of alternating lung opacity and lucency (i.e., heterogeneous lung areas with differing attenuation on CT) *.

- Multiple Potential Causes *

- Small airways disease (bronchiolitis, asthma, bronchiectasis).

- Vascular disorders (chronic thromboembolic hypertension, pulmonary arterial hypertension).

- Alveolar processes (infection, pulmonary edema, organizing pneumonia).

- Interstitial diseases (fibrotic conditions).

- Imaging clues helpful in pinpointing a diagnosis include evidence of large airway involvement, cardiovascular abnormalities, septal thickening, signs of fibrosis, and demonstration of air trapping at expiratory imaging.

- 💡Key Diagnostic Clue: Compare vessel diameter in lucent vs. opaque areas

- Uniform Vessel Diameter:

- Opaque regions are abnormal.

- Indicates infiltrative processes (infection, edema).

- Non-uniform Vessel Diameter:

- Lucent areas are abnormal.

- Smaller vessels in lucent regions.

- Suggests air trapping or vascular disease.

- Uniform Vessel Diameter:

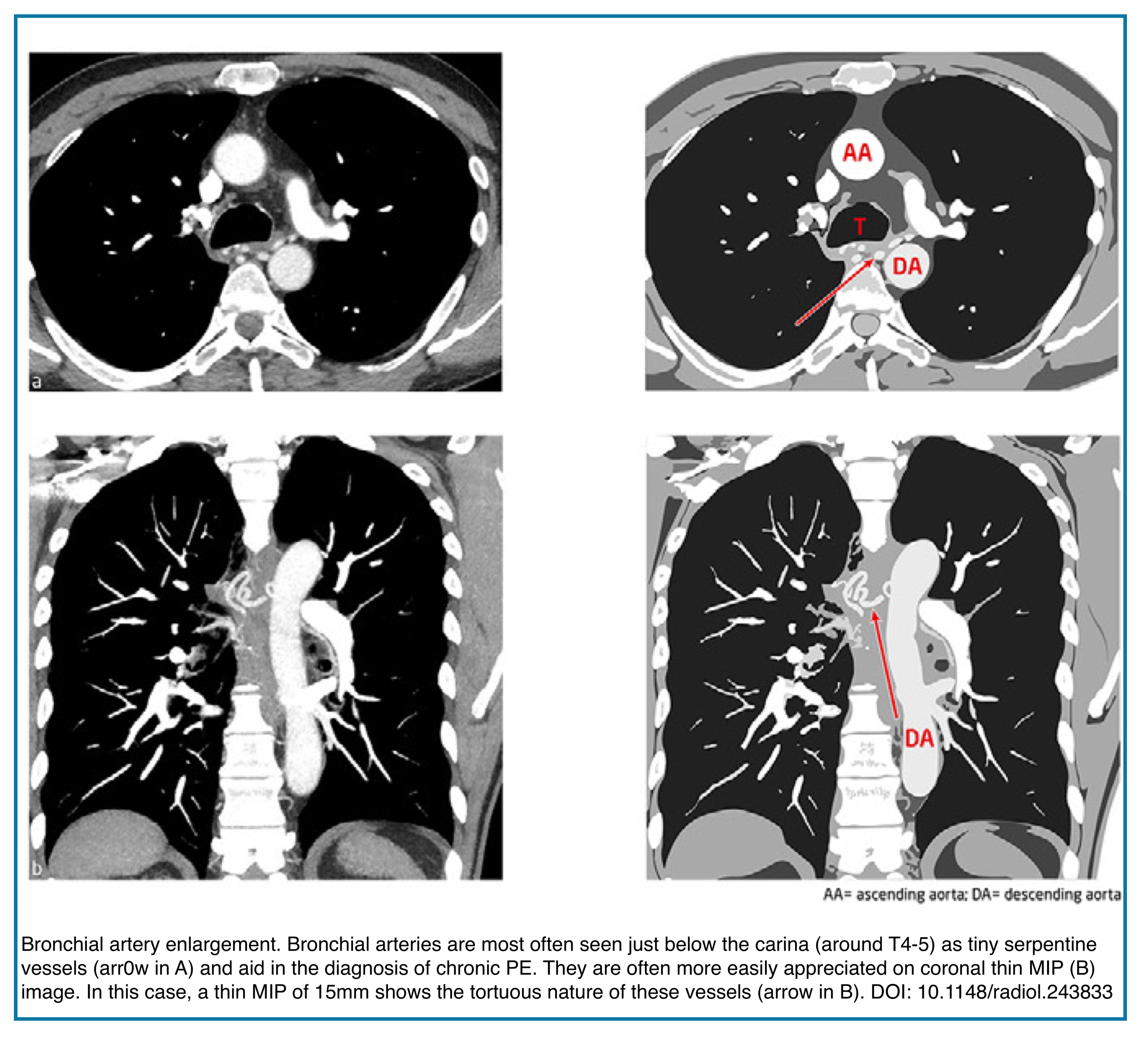

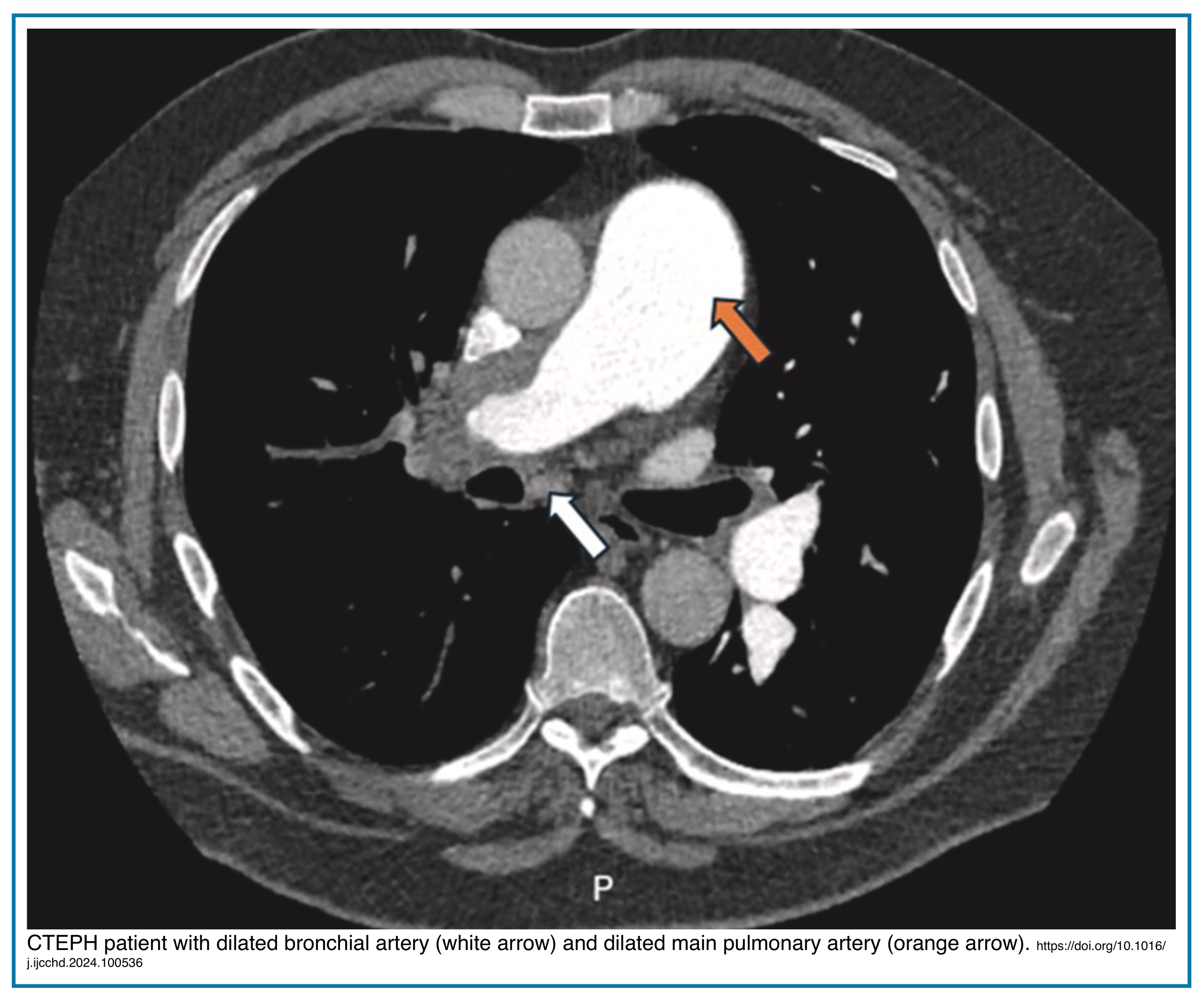

Enlarged Bronchial Arteries

Markedly enlarged bronchial arteries (>1.5 mm diameter in the mediastinum) are one of the most specific signs of chronic disease, indicating long-term compensation (Figures below).

- Not all filling defect on CT angiography represents a pulmonary embolism. Filling defects have different causes.

- A variety of artifacts and mimics can also produce similar appearances *.

- Careful review of the defect in multiple planes (axial, coronal, sagittal) is essential to distinguish true thrombus from alternative causes.

Misinterpreting artifacts or mimics as pulmonary emboli can lead to overdiagnosis and unnecessary anticoagulation. Always review filling defects in multiple planes and, when uncertain, consult radiology.

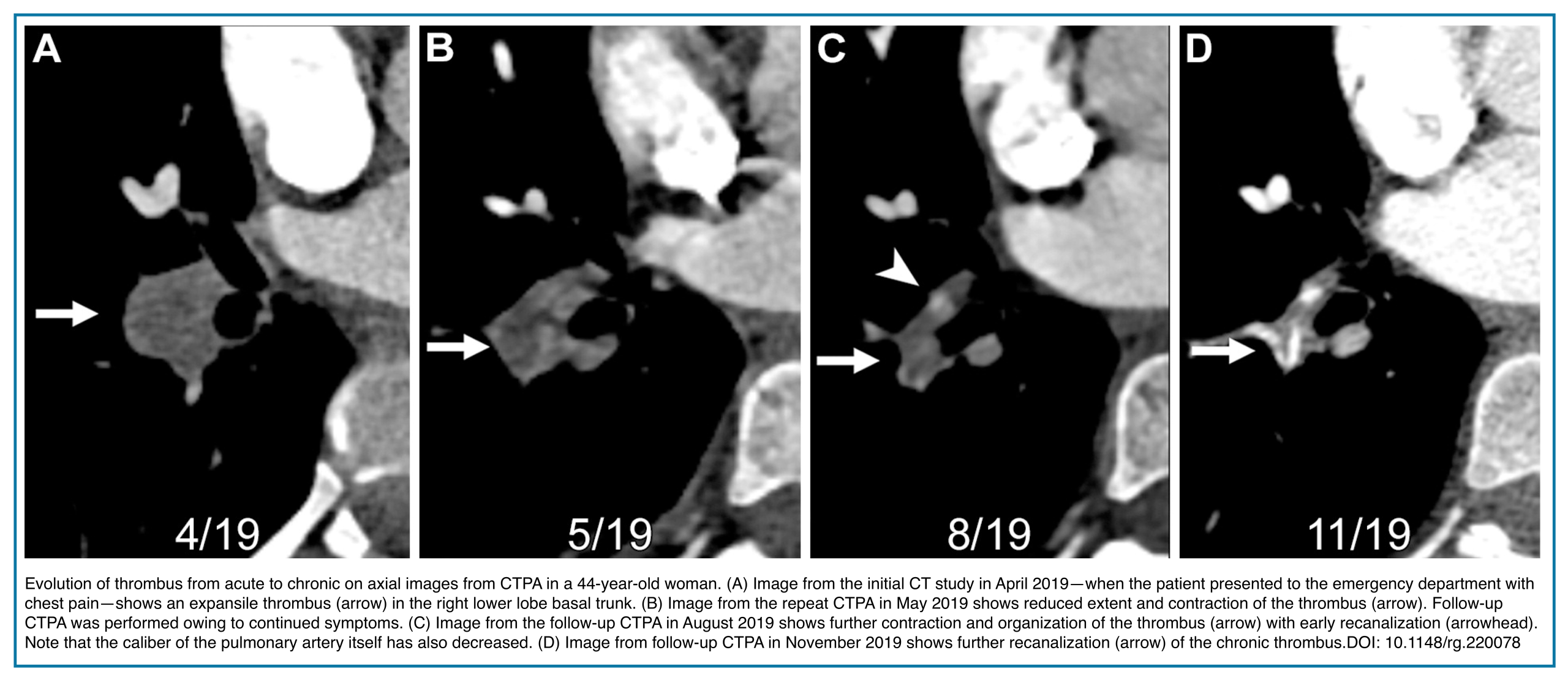

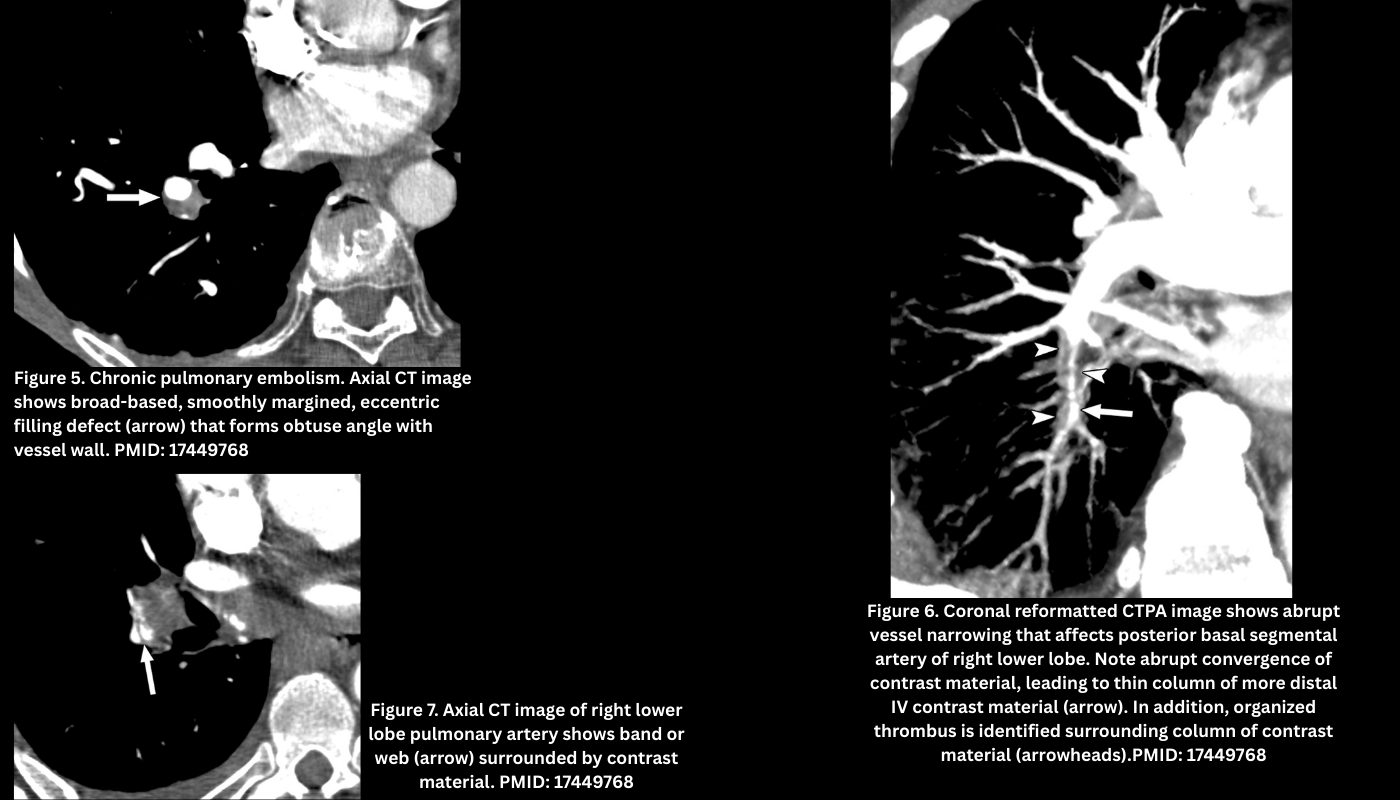

I. Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Disease (CTEPD)

Chronic thromboembolic disease (CTEPD) can mimic acute PE in CTPA but has distinct features that suggest an organized, longstanding process rather than a fresh clot. Recognition is critical, as management differs fundamentally from acute PE. It is also important to recognize that both conditions may co-exist *.

◾️Performance of CTPA

- Sensitivity ~76%, specificity ~96% for CTEPH (limited for distal disease).

- Diagnostic accuracy improves with modern multidetector CT.

A. Clot Appearance In CTPA

◾️The clot shows signs of organization and recanalization (Below left Figure).

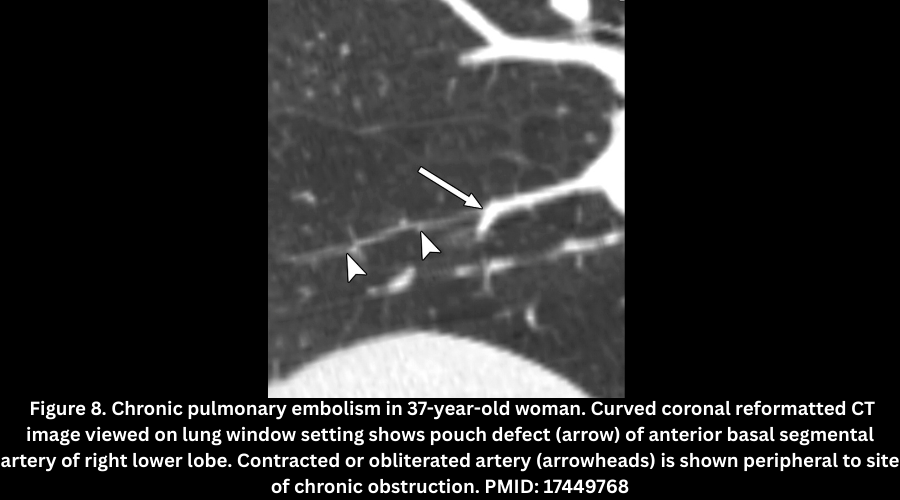

- Webs or bands (thin, linear structures across a vessel).Figure 7.

- Pouch defects (abrupt, concave vessel cut-off with a smaller distal lumen). Figure 6.

◾️The filling defects in CTEPD can be nonocclusive or occlusive.

- Nonocclusive thrombi

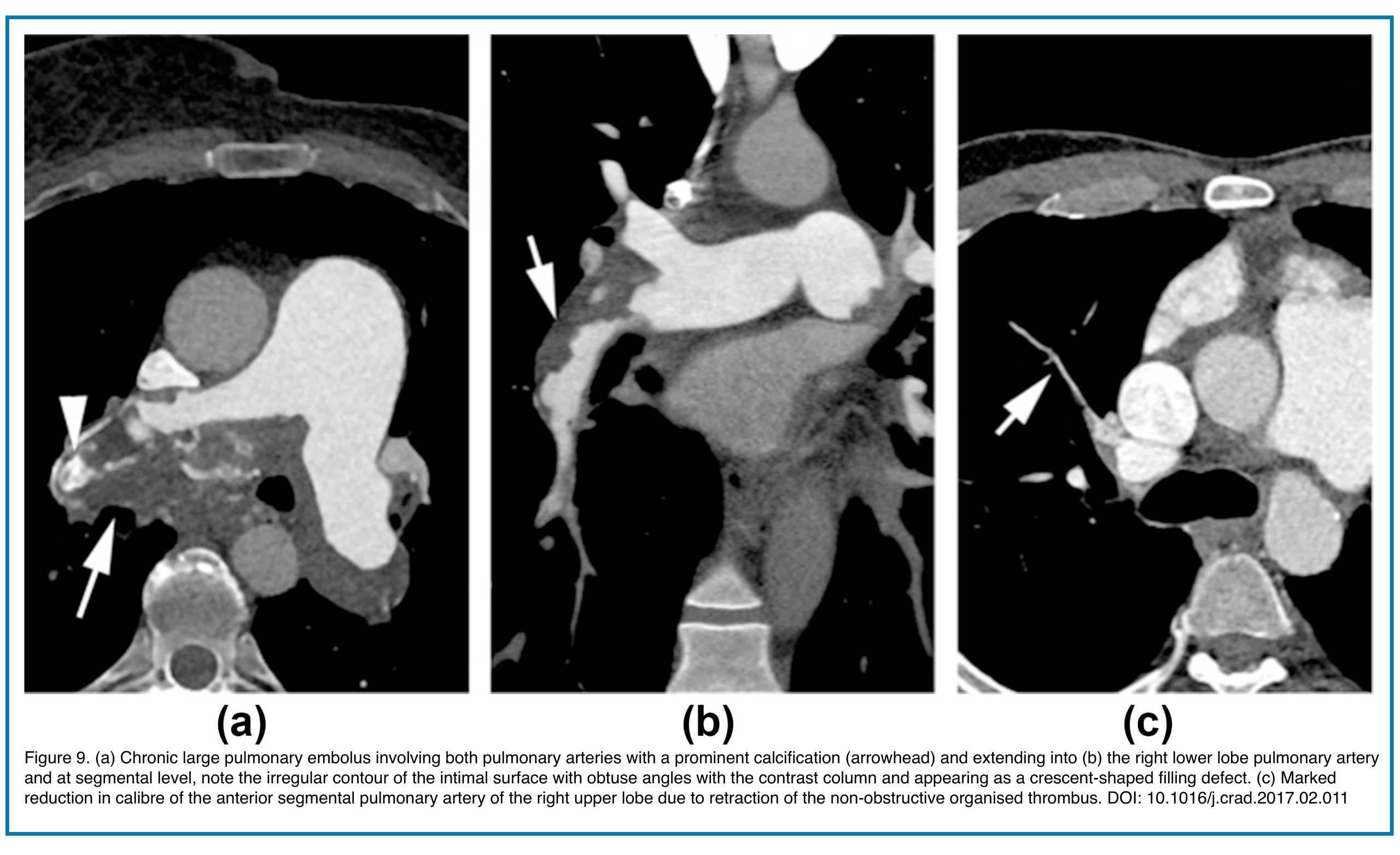

- These can appear as linear filling defects that create bands across the pulmonary arteries, which often intertwine to form webs, or as eccentric thrombi forming an obtuse vessel wall margin that may taper into occlusive thrombi more distally (Figure 5).

- Occlusive chronic thrombus

- They obstruct the vessel lumen and lead to vascular contraction, in contrast to acute thrombus, which distends the vessel.

B. Pulmonary Artery Remodeling

- Vessel shrinkage

- Complete occlusion of a pulmonary artery branch that is permanently smaller than other arteries of the same order (an important distinguishing feature from acute PE, where vessels are often normal or enlarged). Figure 8.

- Vessel Stenosis or Irregularity: Long segments of narrowing or “bizarre, corkscrew” tortuosity of distal arteries due to recanalization.

- Calcification within the chronic clot (rare, but pathognomonic). Figure 9.

C. Systemic Collateral Circulation

- Markedly Enlarged Bronchial Arteries (explained above).

D. Lung Parenchyma Findings (Critical Differentiators)

E. Indirect (physiologic) Features

◾️Main Pulmonary Artery (MPA) Diameter

- MPA dilation is a hallmark of chronic pulmonary hypertension. A diameter of ≥29 mm (or > the diameter of the ascending aorta at the same level) is a key supporting feature.

- This dilation develops over time due to sustained high pressure in the pulmonary arterial system. Its presence strongly argues against a first, isolated acute PE.

◾️Right Ventricular (RV) Enlargement & Strain *

- RV hypertrophy and chronic enlargement are expected findings in established CTEPH (though may be mild or absent in non-hypertensive CTEPD).

- Key Features of Chronicity:

- RV Wall Thickening (>4-5mm): This is the most telling sign of chronicity. The RV muscle hypertrophies over time to compensate for sustained high pressure. Acute PE does not cause RV wall thickening.

- RV Dilation: Often present, similar to acute PE.

- Enlarged Right Atrium and dilated coronary sinus.

- Other signs of chronic pulmonary hypertension: Pruning of peripheral vessels, enlarged pulmonary artery segments.

📊Table

Acute PE vs. CTEPD/CTEPH: CTPA Findings

Comparative imaging features on CT Pulmonary Angiography

| Feature | ACUTE Pulmonary Embolism | CHRONIC Thromboembolic Disease (CTEPD/CTEPH) |

|---|---|---|

| Clot Location & Shape | Central, intraluminal filling defect. If non-occlusive, forms an acute angle (obtuse) with the vessel wall. The clot appears to “float” centrally. | Eccentric, wall-adherent thickening or crescent. If non-occlusive, forms a broad, open angle with the vessel wall, appearing “plastered” against it. |

| Clot Morphology | • “Railway Track” sign (contrast around clot) • May completely occlude a vessel. |

• Webs or bands (thin linear structures) • Pouch defects (abrupt, concave cut-off) • Recanalization (channels within the clot). |

| Artery Appearance at Occlusion | The occluded artery is often expanded or normal in caliber. | The artery is frequently narrowed, stenotic, or irregular. |

| Distal Vessel Patterns | Normal distal vasculature (unless there is prior disease). | “Corkscrew” or tortuous distal vessels due to recanalization and remodeling. |

| Lung Parenchyma (Key Differentiator) |

May show a wedge-shaped infarction (Hampton’s hump) or atelectasis. | Mosaic attenuation pattern (patchwork of light & dark lung regions) – a hallmark sign. |

| Systemic Collateral Circulation | Absent. | Markedly enlarged bronchial arteries (>1.5-2mm) – a highly specific sign. |

| Clot Density/Calcification | Fresh, non-calcified. | May contain calcification (rare but pathognomonic for chronicity). |

| Associated Signs of PH & Chronicity | • MPA usually normal. • RV dilation (RV/LV ratio >1.0) can occur with massive or submassive acute PE, signifying hemodynamic severity and acute pressure overload. The RV wall remains normal in thickness. |

• MPA dilation (≥29 mm). • RV hypertrophy (wall thickening >4-5mm) with or without dilation. • Enlarged right atrium. |

illustration of intravascular features in CTEPD

II. In-Situ Pulmonary Artery Thrombosis

- Definition: A Thrombus that forms directly within pulmonary arteries (not from embolism).

- Key Difference: Originates locally in the pulmonary vasculature (not from DVT).

- Pathogenesis

- Rather than originating from DVT, these thrombi form locally within the pulmonary arteries. This most commonly occurs in the following settings:

- Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) *

- Thrombus formation is secondary, not the primary cause of PH.

- Slow flow or stasis in the often very enlarged central pulmonary arteries.

- Congenital heart disease (CHD) with left-to-right shunting.

- Acute chest syndrome in sickle cell disease

- Pulmonary infections.

- Proinflammatory states have been attributed to this phenomenon (e.g., vessel wall pathology) *

- Postsurgical changes: lobectomy, pneumonectomy.

- Pulmonary artery stenosis.

- Chronic atelectasis.

- Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) *

- Rather than originating from DVT, these thrombi form locally within the pulmonary arteries. This most commonly occurs in the following settings:

- Recognition is crucial, as its management and prognostic implications may differ from embolic PE.

◾️Key Features (CTPA & Clinical Context)

- 🩻Imaging Characteristics

- Wall-adherent (wall lining).

- Typically non-occlusive, so downstream lung perfusion may remain intact *.

- V/Q scans may appear normal (helps distinguish from CTEPH).

- Calcification of the pulmonary artery walls.

- No mosaic perfusion or bronchial collaterals, which are typical of chronic embolic disease.

- Differentiating from other entities

- Acute PE → Intraluminal, central filling defect, often occlusive, acute angles.

- CTEPD → Webs, bands, stenoses, post-stenotic dilation, mosaic perfusion.

- In-situ thrombosis → Wall-hugging clot in dilated pulmonary arteries, non-occlusive, associated with PH.

💡 Clinical Pearl:

- Identification of in-situ thrombosis does not imply causation of pulmonary hypertension. Rather, it is often a consequence of longstanding vascular disease. Always interpret in the broader hemodynamic and clinical context.

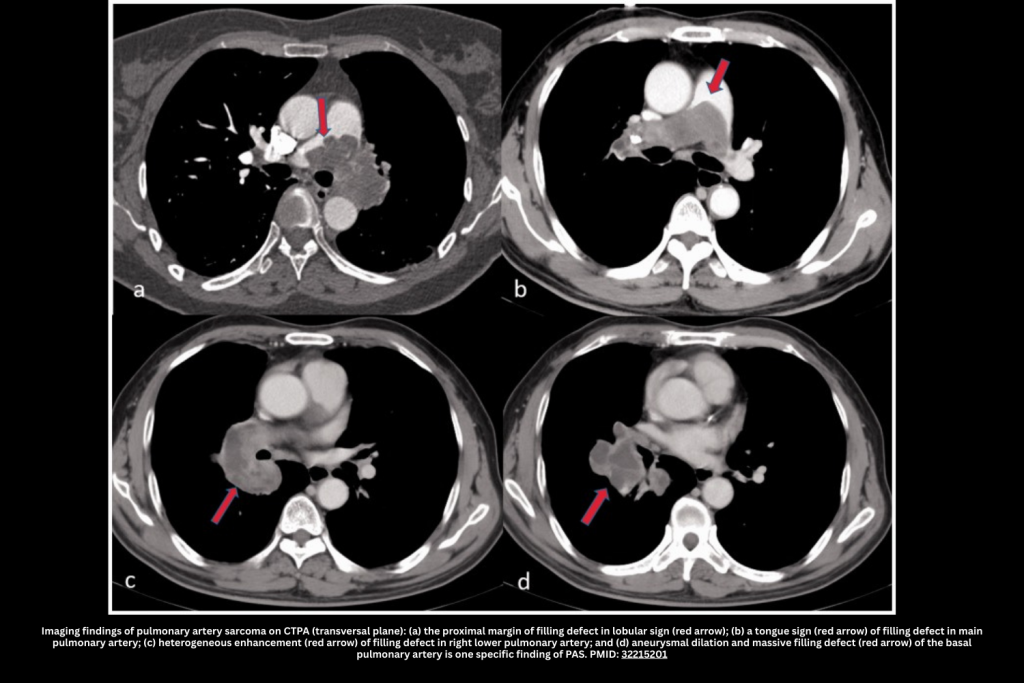

III. Pulmonary Artery Sarcoma (PAS)

Pulmonary artery sarcoma (PAS) is a rare but critical mimic of pulmonary embolism. Unlike embolic disease, it represents a primary malignant tumor of the pulmonary artery, most often diagnosed in middle age.

◾️Key Features (CTPA & Clinical Context):

- Epidemiology & Presentation

- Typically presents between 45–55 years; rare in patients <30.

- Gradual onset of pulmonary hypertension and RV failure over months.

- Symptoms are often mild compared to dramatic CT findings.

- Red flags: Constitutional symptoms (fever, weight loss, night sweats) and failure to improve with anticoagulation.

- 🩻Imaging Clues

- Most common findings:

- A Lobulated or nodular appearance is often seen.

- A single, central lesion tends to occur (unlike a pulmonary embolism, which frequently causes multiple, bilateral filling defects).

- Filling of the entire arterial lumen (“eclipsing vessel sign”).

- Most common findings:

- More specific features that may occasionally be seen:

- Vessel expansion due to mass effect.

- Invasion of the lung parenchyma or mediastinum.

- Hematogenous metastasis causes randomly distributed nodules in the lung parenchyma.

- Calcification may occur; if encountered, this suggests against PE (although calcification can also occur in the context of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension).

- Lesions may have low attenuation. Heterogeneous contrast enhancement may occur (although this won’t be captured on a CT angiogram).

- Diagnosis

- Consider when CT findings are disproportionate to symptoms or when “PE” does not resolve with treatment.

- MRI or PET can support diagnosis; tissue confirmation via endovascular biopsy or surgical resection.

💡 Clinical Pearl:

Always suspect PAS in patients with a “PE” that is solitary, central, enlarging, or unresponsive to anticoagulation — especially with systemic symptoms.

IV. Other mimics of Acute PE on CTPA

- Pulmonary tumor embolism

- Unlike thrombus, embolic tumor fragments originate from intravascular extension of malignancies or intracardiac masses.

- Helpful clues:

- Symptoms are often mild compared to dramatic CT findings.

- 🩻Imaging Clues

- Most common findings:

- A Lobulated or nodular appearance is often seen.

- A single, central lesion tends to occur (unlike a PE, which frequently causes multiple, bilateral filling defects).

- Filling of the entire arterial lumen (“eclipsing vessel sign”).

- More specific features that may occasionally be seen:

- Vessel expansion due to mass effect.

- Invasion of the lung parenchyma or mediastinum.

- Hematogenous metastasis causes randomly distributed nodules in the lung parenchyma.

- Calcification may occur; if encountered, this suggests against PE (although calcification can also occur in the context of CTEPH).

- Most common findings:

- 💡 Clinical Pearl:

Think of pulmonary tumor embolism when a patient with known or suspected malignancy has central filling defects that look atypically smooth, rounded, or enlarged on repeat imaging — anticoagulation won’t help, and intervention may be needed.

- Foreign body emboli

- Represent iatrogenic or procedural material lodged in the pulmonary arteries. Unlike thrombus, these emboli are non-biological and usually follow invasive procedures, e.g., catheter fragments, cement emboli from vertebroplasty/kyphoplasty.

- Imaging Characteristics: Appear as high-attenuation intravascular objects rather than soft-tissue filling defects.

V. Artifacts

- Artifacts can mimic or obscure emboli. The two pillars of avoiding misreads are:

- Adequate opacification, and

- Motion-free, analyzable distal vessels.

- Aim for mean PA enhancement ≈ 200–250 HU on modern scanners (qualitative homogeneity acceptable).

- If image quality is degraded, repeat with a corrected protocol rather than rendering indeterminate reports.

💡 Clinical/Radiology Pearls

- Always window/level for embolus detection and inspect >1 plane/slice; confirm defects persist across consecutive images to avoid mistaking flow/motion for clot.

- Coach breathing (mild inspiration or simple apnea) to reduce transient interruption of contrast (TIC) and Valsalva-related mixing.

- When only central PAs are analyzable, label the study indeterminate; if segmental/sub-segmental levels are analyzable and negative, the exam can be “truly negative.” Document analyzability.

- If nondiagnostic, identify the cause (e.g., motion, low HU, TIC) and repeat with targeted fixes (delay, higher iodine flux, caudo-cranial pass, shallow breathing, etc.).

| Artifact / Pitfall | How It Looks / Why It Happens | Fix / Prevention (Protocol & Reading Tips) |

|---|---|---|

| Transient Interruption of Contrast (TIC) | Segment(s) of PA with low attenuation between denser proximal/distal segments due to influx of unopacified IVC blood (often after deep inspiration/“big breath”). | Coach mild inspiration or simple apnea; avoid prescan hyperventilation; consider caudo-cranial acquisition; repeat if needed. |

| Early Timing / Poor Opacification | Globally under-opacified PAs; pseudo–filling defects/“washed-out” appearance; risk with low cardiac output, early bolus, dilution/mixing. | Target mean PA ≈ 200–250 HU on current scanners; increase iodine flux (higher kV strategy or higher concentration/rate), adjust start delay/bolus tracking ROI, use larger-gauge/fenestrated IVs; repeat scan if nondiagnostic. |

| Respiratory Motion | Blurring, stair-step vessel edges; “defects” that shift across slices; most pronounced at lung bases. | Fast rotation, high pitch; consider caudo-cranial scan; shallow breathing if unable to hold full inspiration. |

Reading checks: confirm across consecutive slices & planes; use HU measurements; correlate mediastinal + lung windows before calling a clot.

Types of Artifacts

Artifacts arise from patient factors, technical issues, anatomic structures, or pathology, and they can mimic or obscure pulmonary embolism. Recognizing their characteristic appearance is key to avoiding misdiagnosis

| Category | Artifact / Mimic | Appearance & Key Clues |

|---|---|---|

| Patient-Related | ||

| Respiratory motion | Blurring / “seagull sign” | Vessels shift or blur across slices, esp. lower lobes; best seen on lung windows. |

| Flow-related (TIC) | Patchy low attenuation | Poor mixing of contrast/unopacified blood in lower lobes; ill-defined margins; HU often >78. |

| Technical | ||

| Streak artifact | Dense SVC contrast | Radiating streaks over RPA/upper lobes; reduced by saline chaser. |

| Partial volume | Blurred lumen edges | Thick slices / axial only; defect not seen on contiguous slices. |

| Stair-step | Low-attenuation lines | On coronal/sagittal MPR from motion/recon gaps; reduced with overlap. |

| Anatomic | ||

| Lymph node averaging | Smooth extrinsic impression | Overlaps vessel lumen; contour preserved → not true clot. |

| Vascular bifurcation | Branching point mimic | Linear defect at branch; confirm on multiplanar reformats. |

| Vein mis-ID | Unopacified pulmonary vein | May be mistaken as PA with clot; trace to LA to confirm venous anatomy. |

| Pathologic Mimics | ||

| Mucus plug | Dilated mucus-filled bronchus | Mimics intravascular clot; adjacent contrast-filled artery helps differentiate. |

| Perivascular edema | Peribronchovascular thickening | Seen in CHF; with septal thickening, pleural effusion, ground-glass opacities. |

| Hypoxic vasoconstriction | Poorly opacified vessels in collapse | Due to consolidation/atelectasis; attenuation often >78 HU; resolves with delayed scan. |

Reading tip: Confirm suspected defects on multiple planes and windows, correlate with HU values, and always consider artifact or mimic before calling clot.

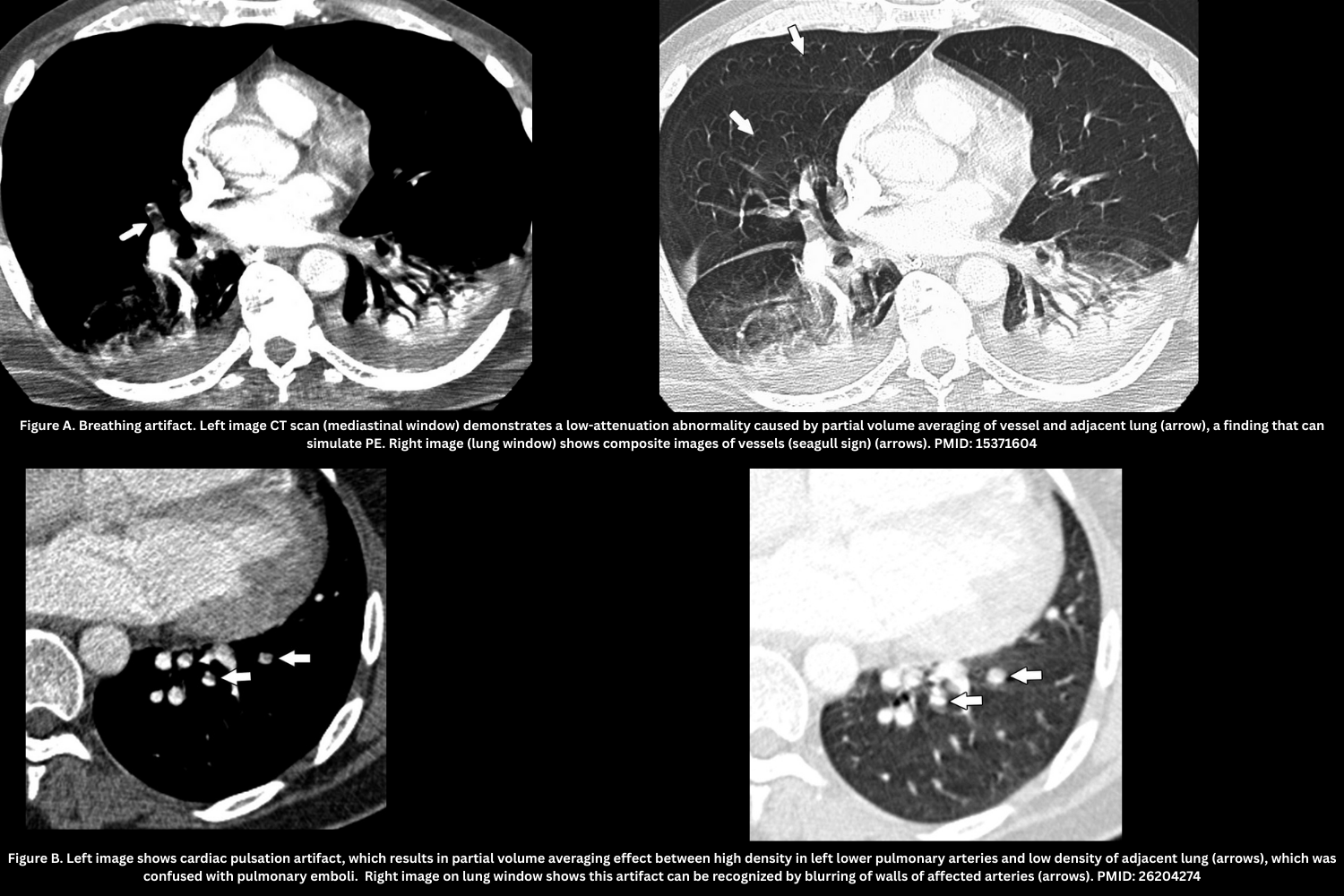

Patient-Related Artifacts

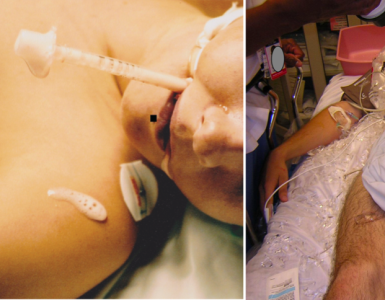

- Motion artifact (breathing artifact, cardiac pulsation artifact). Figure A, B.

- Blurring, “seagull sign,” shifting vessel position across slices.

- Best seen on lung windows.

- Leads to an indeterminate diagnosis at that level.

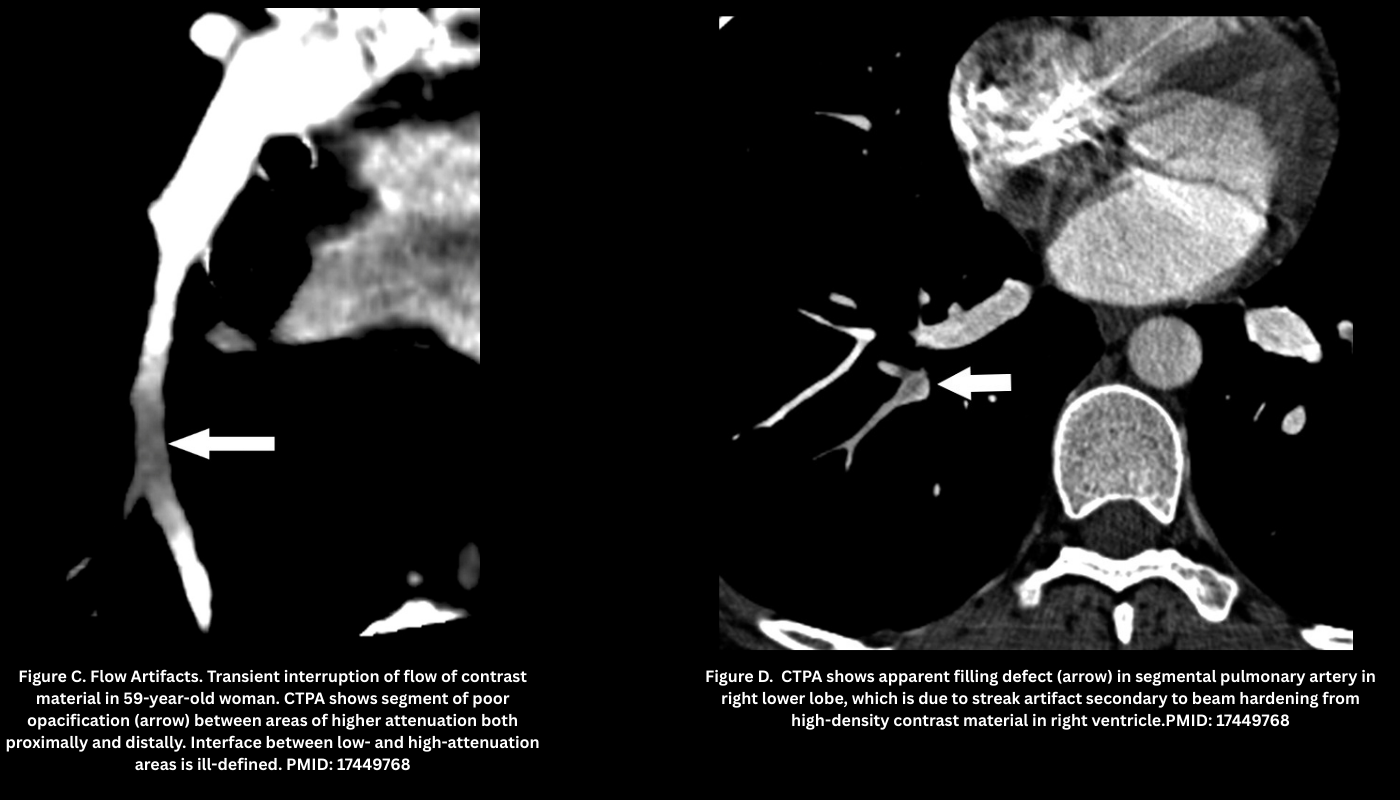

- Flow-related artifact (transient interruption of contrast). Figure C.

- Poor mixing of contrast/unopacified blood → patchy low attenuation in lower lobe arteries.

- Appearance: Filling defect with poorly-defined margins from mixing of opacified and unopacified blood (“transient interruption of contrast”), attenuation >78 HU.

- Caused by deep inspiration or IVC inflow; reduced with mild inspiration or apnea coaching.

Technical Artifacts

- Beam-Hardening Artifact (Figure D)

- Appearance: Dense streaks from high-density structures (e.g., pooled contrast agent in the right atrium, SVC or other adjacent vessels, metallic structures such as pacemakers, or the patient’s arms if they cannot be elevated above the chest), often projecting over the right pulmonary artery or medial upper lobe vessels.

- Pearl: Use a saline chaser and optimized bolus protocols to reduce SVC streaking.

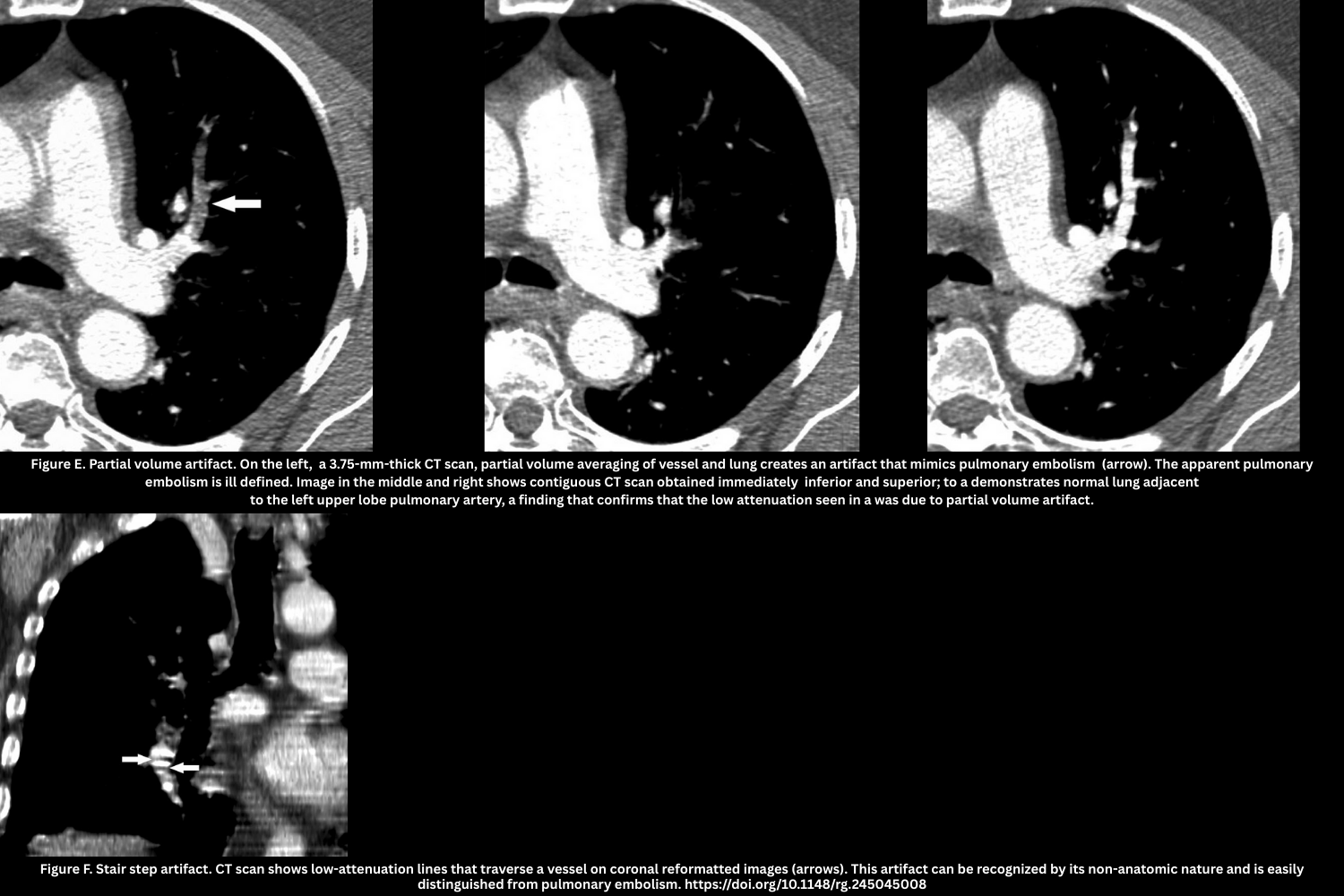

- Partial volume artifact (Figure E)

- Thick slices/axial orientation cause blurred low-attenuation defects.

- Partial volume artifact is caused by the CT system averaging varying tissue densities within a single voxel, leading to blurred edges or incorrect CT numbers at tissue interfaces

- Not reproducible on contiguous slices.

- Thick slices/axial orientation cause blurred low-attenuation defects.

- Stair-step artifact (Figure F)

- The stair-step artifact consists of low-attenuation lines seen traversing a vessel on coronal and sagittal reformatted images and is accentuated by cardiac and respiratory motion.

- Reduced with overlapping reconstructions.

Anatomic Artifacts

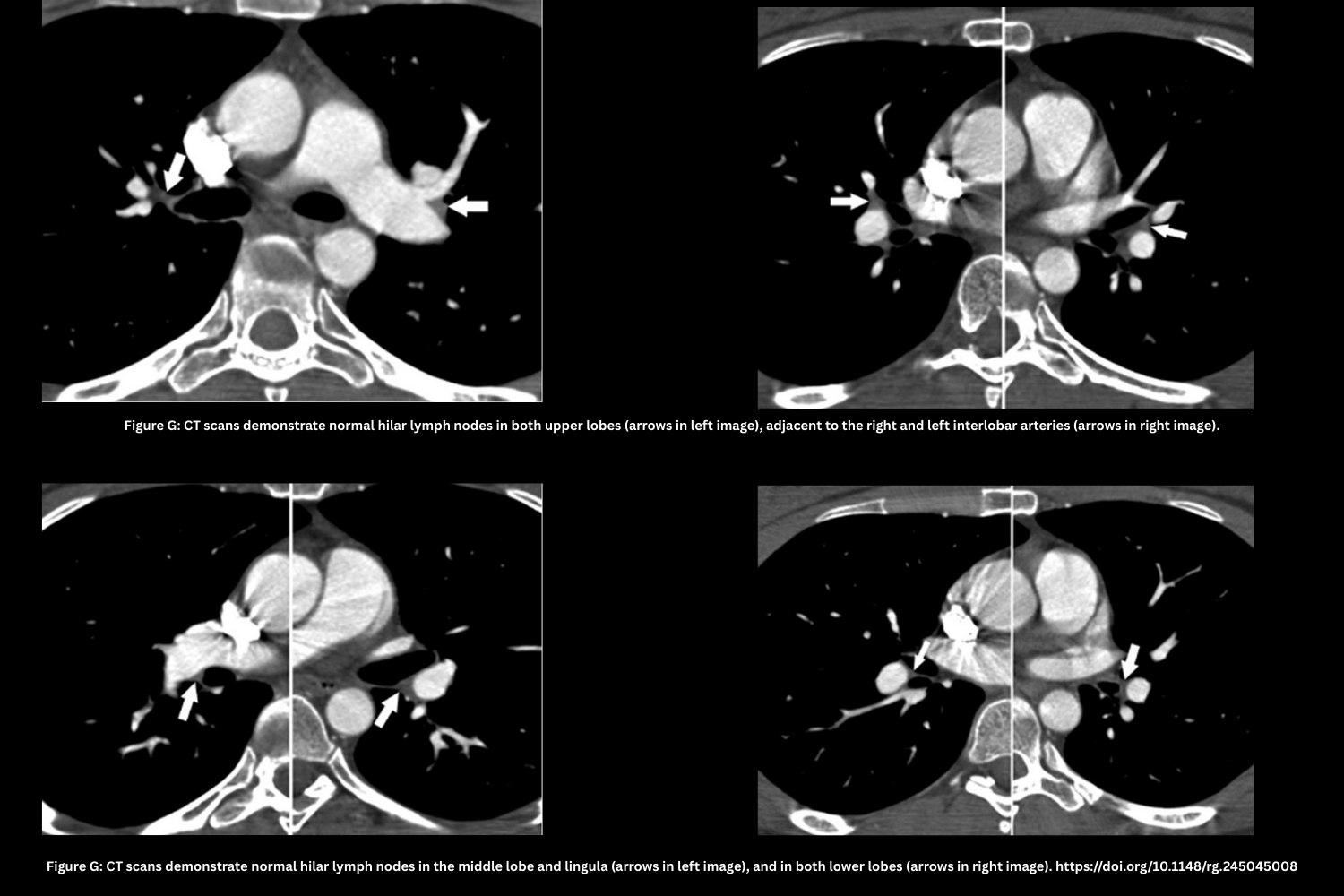

- Partial Volume Averaging Effect in Lymph Nodes (Figure G)

- Hilar lymph nodes overlap the vessel lumen in thick slices.

- Preserved smooth vessel contour distinguishes it from a clot.

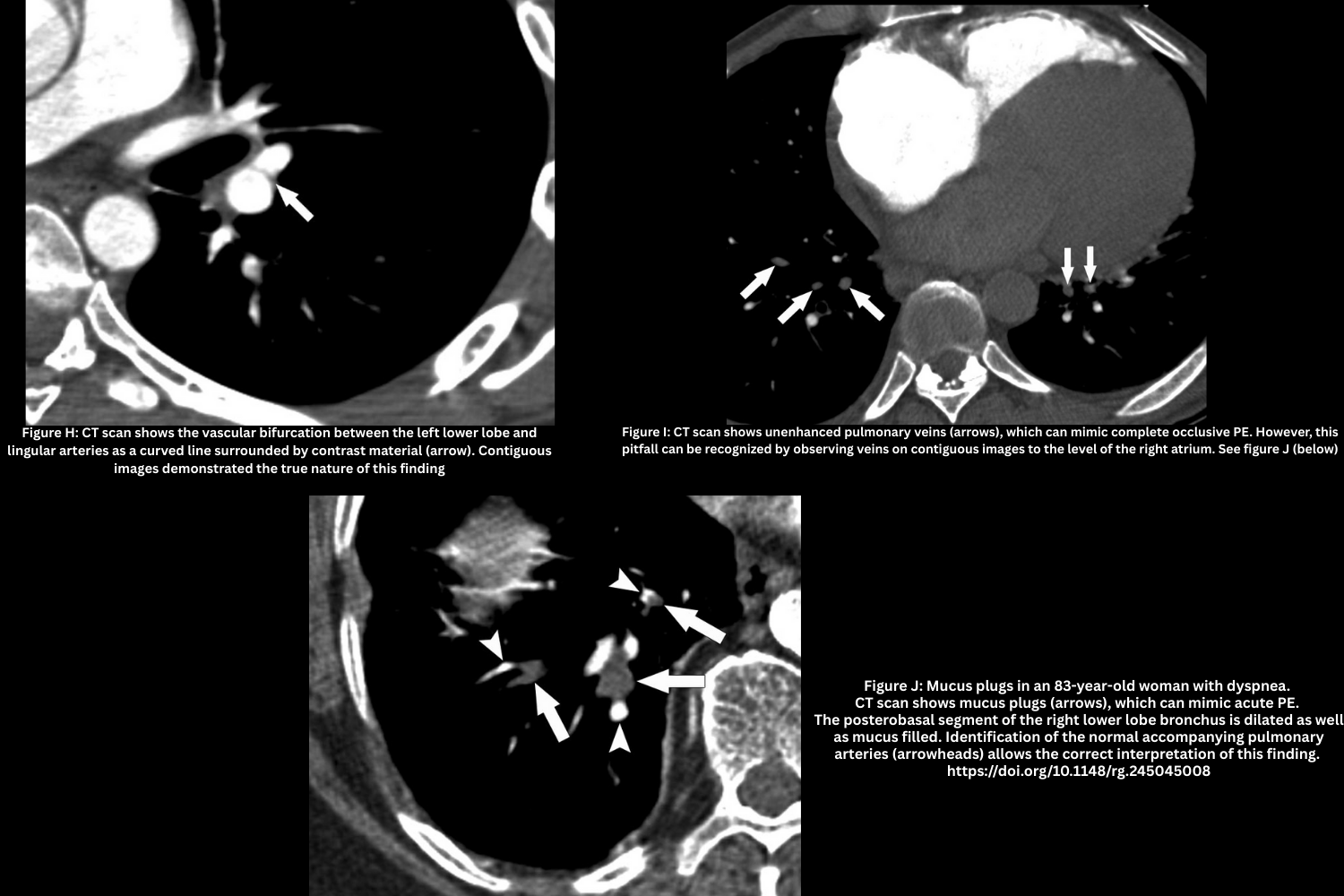

- Vascular bifurcation (Figure H).

- On axial images, vascular bifurcations may simulate linear filling defects

- Confirm with multiplanar reformats (Sagittal and coronal images can help identify these normal anatomic structures).

- Vein misidentification (Figure I).

- Unopacified pulmonary veins may be mistaken for arteries with a clot.

- Trace vessels to the left atrium to confirm venous anatomy.

Pathologic Mimics

- Mucus plug (Figure J, above).

- Dilated, mucus-filled bronchus mistaken for intravascular thrombus.

- Normal contrast-filled artery adjacent helps differentiate.

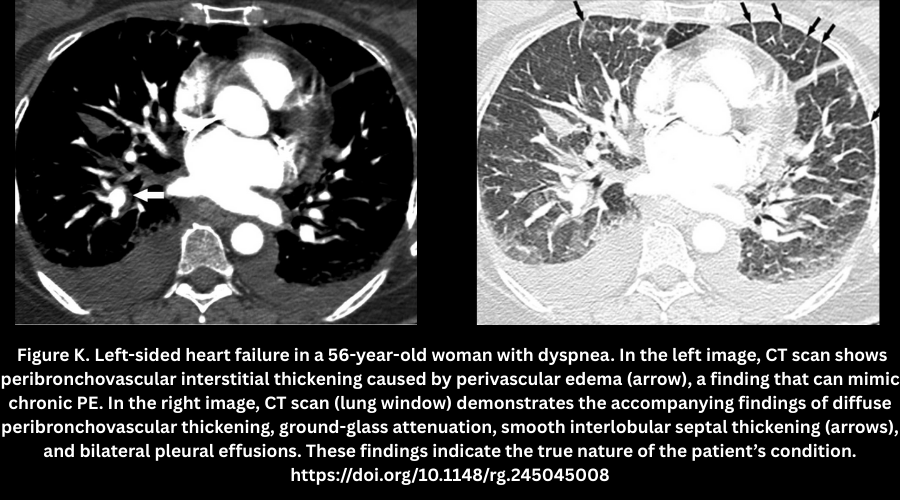

- Perivascular edema (Figure K).

- Seen in CHF; causes peri-bronchovascular thickening that resembles chronic PE.

- Accompanied by ground-glass opacities, septal thickening, and pleural effusions.

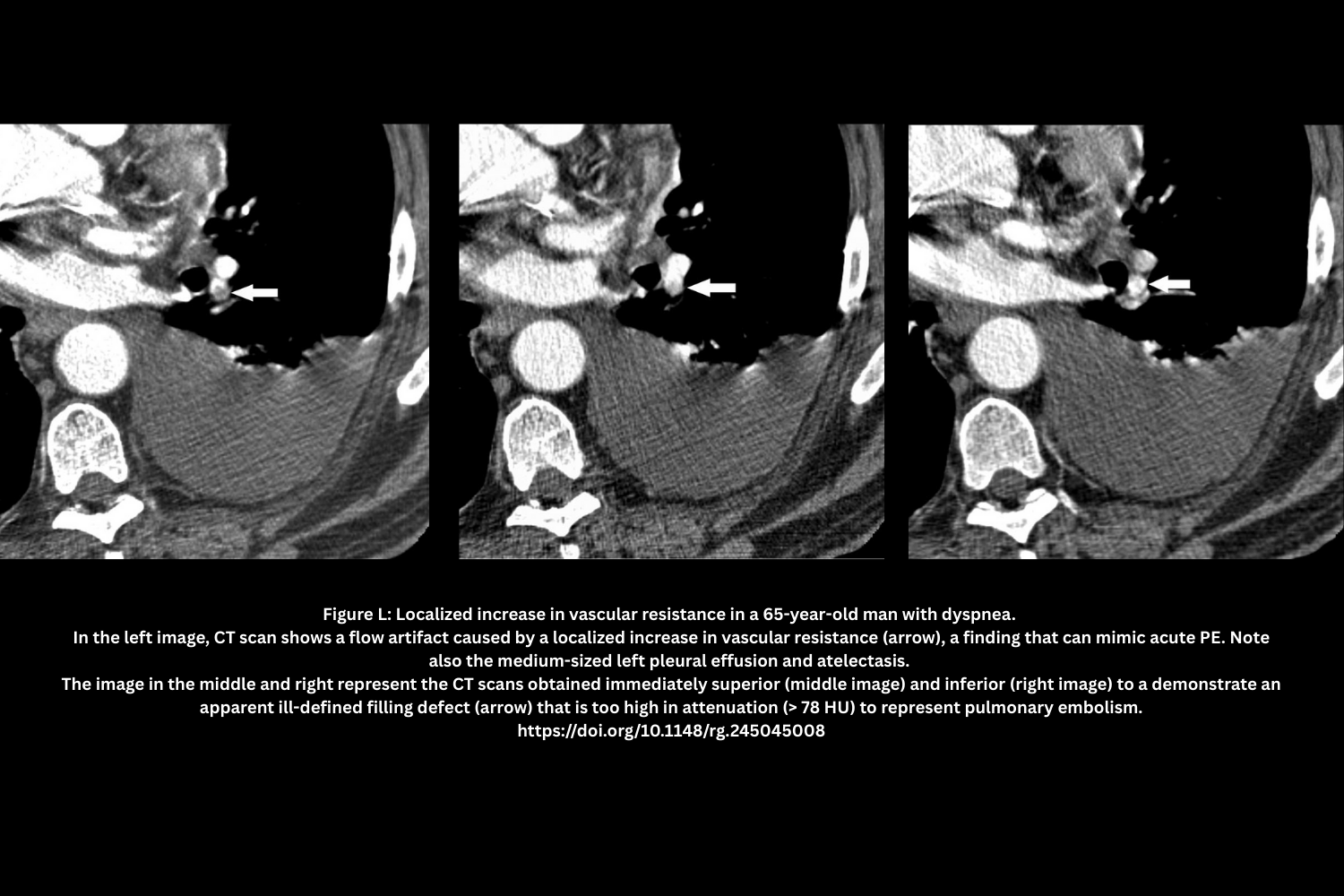

- Localized hypoxic vasoconstriction (Figure L)

- Consolidation/atelectasis → Sluggish or unopacified flow mimicking a clot.

- Attenuation often >78 HU; repeat scan with delay may clarify.

Every suspected intraluminal defect must be confirmed on >1 plane and across consecutive slices, with careful review of vessel anatomy and attenuation values. True emboli conform to the vessel lumen, while artifacts often have ill-defined margins, cross planes, or appear in nonanatomic patterns.

4. Ventilation/Perfusion (V/Q) Scan

◾️Overview

- V/Q scanning is a nuclear medicine test that evaluates the match between ventilation and perfusion. While historically central in PE diagnosis, its modern role is limited. It is most useful in selected patients (e.g., pregnancy with normal CXR, contrast allergy, renal failure) where CT angiography is undesirable.

◾️Optimal Conditions for a V/Q Scan

- Normal chest radiograph (abnormal CXR decreases interpretability).

- No prior chronic PE (avoids confusing perfusion defects).

- Ability to perform breath-holding during the ventilation phase.

- Hemodynamic stability (most critically ill/intubated patients cannot undergo full V/Q testing).

◾️Interpretation

- High-probability scan

- LR ≈ 18 → generally diagnostic for PE.

- Intermediate-probability scan

- LR ≈ 1.2 → nondiagnostic, adds little value.

- Low-probability scan

- LR ≈ 0.4 → may exclude PE in low-pretest patients, but not if intermediate/high pretest probability.

- Normal scan

- LR ≈ 0.05 → essentially rules out PE.

◾️Limitations & Contemporary Use

- Not first-line: In the modern era, virtually all patients can undergo CTPA.

- Renal insufficiency & contrast allergy are not absolute barriers — most can still undergo CTPA with hydration or steroid pretreatment.

- High rate of indeterminate results: ~50% inconclusive; contributes diagnostic value in <30% of patients (ERS Handbook).

- Limited diagnostic scope: Cannot evaluate for alternative thoracic diagnoses (e.g., pneumonia, dissection, malignancy).

- Pregnancy: An isolated perfusion-only scan can be considered if CXR is normal, with a Foley catheter and hydration to reduce fetal bladder dose.

V/Q scanning is a niche test. Reserve it for select scenarios (e.g., pregnancy with normal CXR, rare true contraindication to CTPA).

In most patients, CTPA provides greater diagnostic accuracy and evaluates alternative thoracic pathology.

When a V/Q is performed, interpret results in the context of pretest probability (high ≈ diagnostic; normal ≈ rules out; intermediate = nondiagnostic).

Diagnosing PE

Testing threshold & optimal miss rate

◾️Background

- More than 12% of patients who present to the ED have chest pain or dyspnea. However, not all of these require an evaluation for PE.

- The mere presence of epidemiologic risk factors does not automatically justify a PE workup.

- Nearly all ED patients have some background risk factor for PE, including age, obesity, or hormonal therapy.

- Over-testing for PE: Why Restraint Matters

- Emergency clinicians currently evaluate ~2% of all ED patients with CTPA, and even more undergo D-dimer testing. However, indiscriminate use of D-dimer and CTPA is harmful:

- D-dimer overuse drives unnecessary downstream imaging.

- CTPA carries risks — ionizing radiation, IV contrast exposure, and the danger of false-positive findings that may lead to unwarranted anticoagulation.

- The key is to balance the true likelihood of PE against the potential harms of testing, reserving advanced imaging for patients whose pretest probability justifies it.

- Emergency clinicians currently evaluate ~2% of all ED patients with CTPA, and even more undergo D-dimer testing. However, indiscriminate use of D-dimer and CTPA is harmful:

◾️When Should We Test for Pulmonary Embolism?

- The decision to evaluate for pulmonary embolism should be guided by pretest probability, not reflexive testing. Not every patient with dyspnea, chest pain, or syncope benefits from a PE workup, and in some, testing may cause more harm than good.

- Concept of test threshold

- The test threshold is the point below which testing is more likely to harm than benefit the patient.

- For PE, the test threshold is ~ 2% *.

- Below threshold (< 2% probability): Patients are more likely to be harmed than helped by testing (e.g., due to complications from diagnostic tests, or false-positive results). Avoid D-dimer or CTPA in this group.

- Above threshold (>2% probability): Patients are more likely to benefit from testing, unless an alternative diagnosis convincingly explains their symptoms.

- Alternative Diagnoses at the Bedside

- Simple bedside tests such as history, physical exam, chest radiograph, EKG, and cardiopulmonary POCUS frequently reveal other causes (e.g., pneumonia, pneumothorax, CHF, pericarditis).

- Identifying an alternative diagnosis often decreases the likelihood of PE enough to avoid unnecessary testing.

- Simple bedside tests such as history, physical exam, chest radiograph, EKG, and cardiopulmonary POCUS frequently reveal other causes (e.g., pneumonia, pneumothorax, CHF, pericarditis).

- Optimal miss rate for PE

💡 For PE, the test threshold is ~2%, which aligns with the accepted miss rate of 1–2%. Notably, patients with low-risk Wells scores (0–1 points) have an estimated PE prevalence of ~1–3%, a probability that sits very close to this threshold

💡Bottom line

- Evaluating suspected PE begins with bedside assessment of probability and alternative diagnoses, then transitions to formal prediction tools (Gestalt, Wells, Geneva, PERC).

- Testing is justified only when the probability exceeds the harm threshold, and no better alternative explanation for the presentation is available.

Despite the high burden of PE, it is neither practical nor safe to test every patient with nonspecific symptoms. In diagnostic medicine, we apply the concept of a testing threshold—the minimum disease probability above which testing provides more benefit than harm. For PE, this threshold is about 2%, which aligns with the accepted miss rate of 1–2%. Striving for zero missed cases is not an achievement; it usually reflects over-testing, over-diagnosis, and unnecessary iatrogenic harm.

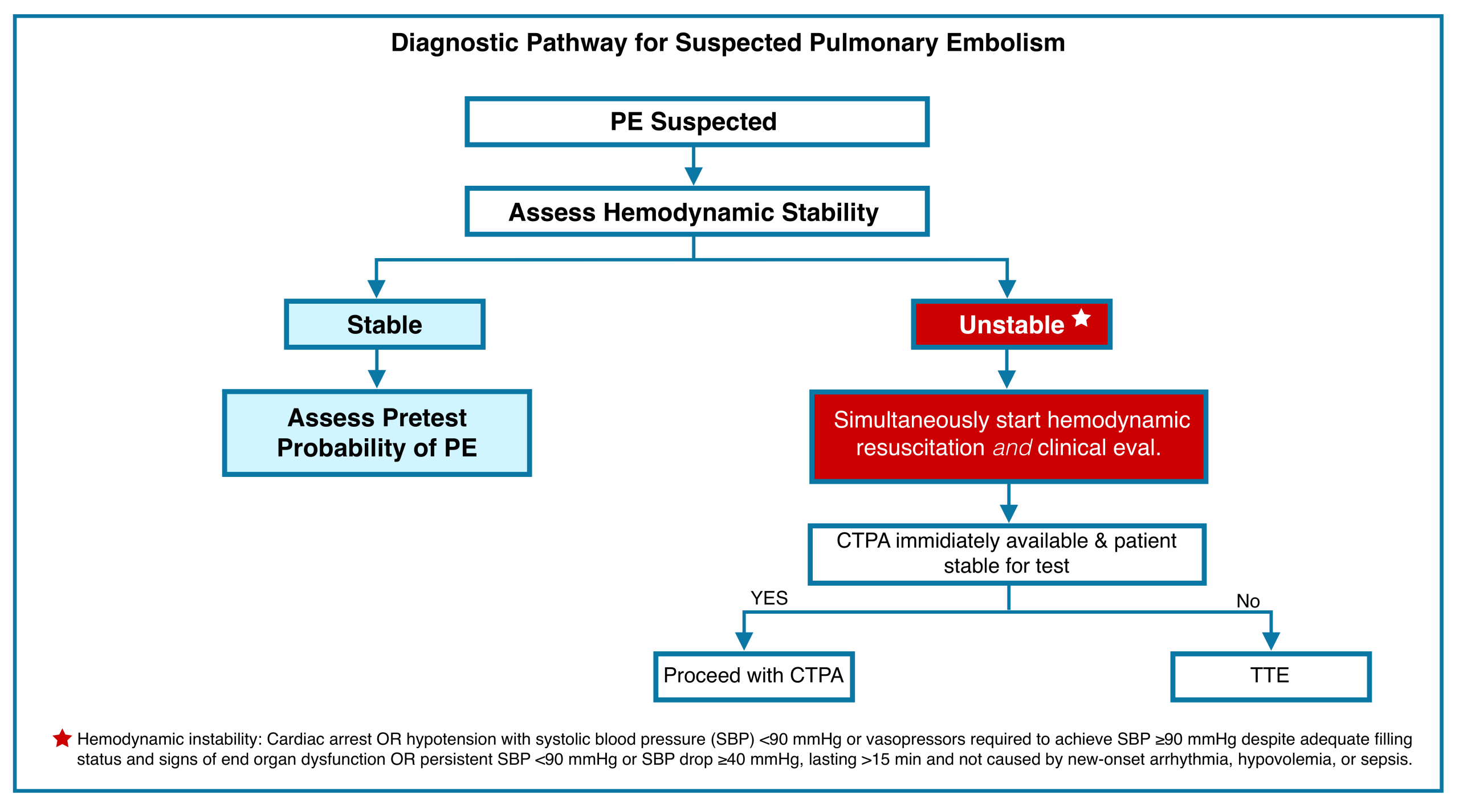

General Approach to Diagnosis of PE

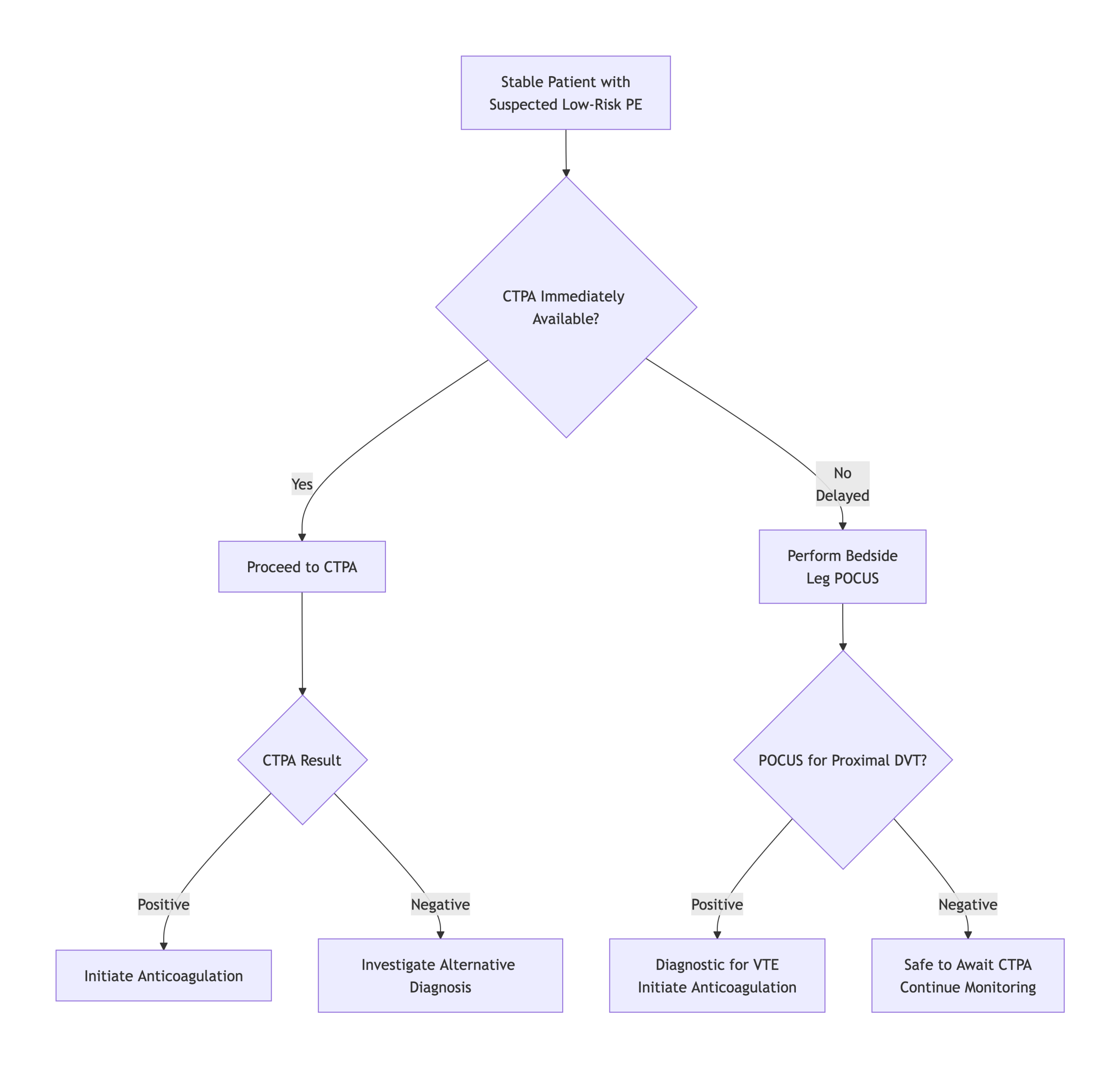

◾️The diagnostic pathway for suspected PE should be tailored to hemodynamic status *. Figure below.

- For unstable patients, a swift approach using bedside echocardiography or CTPA (if feasible) is critical to establish the diagnosis and initiate life-saving intervention *. This is discussed here.

- Diagnostic evaluation of PE in stable patients is discussed below.

Approach to Diagnosis of PE in Stable Patients

1# Initial evaluation

- Start with the Right Question: “Why does the patient have respiratory/cardiovascular dysfunction?”

- When faced with a patient in the ED with dyspnea, chest pain, or syncope, the first task at the bedside is not simply to ask, “Does this patient have a PE?” but rather, “Why is this patient short of breath or unstable?”

- History, physical exams, EKG, CXR, bedside cardiopulmonary ultrasound, and DVT ultrasound (especially in pregnancy) can often reveal alternative diagnoses (e.g., pneumonia, pneumothorax, CHF, pericarditis) that make PE less likely.

- When faced with a patient in the ED with dyspnea, chest pain, or syncope, the first task at the bedside is not simply to ask, “Does this patient have a PE?” but rather, “Why is this patient short of breath or unstable?”

2# Estimate Pretest Probability (PTP)

- The PTP guides what (if any) objective testing for PE should be performed and whether empirical therapy should be initiated.

- There are several acceptable methods for estimating PTP, including;

- Clinical experience, or “gestalt.”

- Several clinical scoring systems, such as the Wells Score and the Revised Geneva Score (both are well-validated). Table below.

- Whether to use clinical gestalt or risk stratification tools

- A meta-analysis of prospective studies found that the sensitivity of clinician gestalt was comparable to that of risk stratification tools; however, the specificity of risk stratification tools was higher (81% versus 52%), suggesting that risk stratification tools may have value in decreasing imaging studies *.

- A randomized trial of PERC reported 9.7% fewer imaging studies compared with usual care *.

| Pulmonary Embolism Clinical Probability Score | Original / Revised (Score) |

Pulmonary Embolism Clinical Probability Score | Revised (Score) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wells Score | Value | Geneva Score | Value |

| Clinical signs & symptoms of DVT | 3 | Age ≥65 years | +1 |

| Alternative diagnosis less likely than PE | 3 | Previous DVT or PE | +3 |

| Heart rate >100 bpm | 1.5 | Surgery or fracture within 1 month | +2 |

| Immobilization ≥3 days OR surgery in prior 4 weeks | 1.5 | Active malignant condition | +2 |

| Previous DVT/PE | 1.5 | Hemoptysis | +2 |

| Hemoptysis | 1 | Heart rate 75–94 bpm | +3 |

| Active cancer (≤6 months or ongoing) | 1.5 | Heart rate ≥95 bpm | +5 |

| Pain on deep palpation of lower limb & unilateral edema | +4 | ||

| Clinical Probability of PE — Category Cutoffs | |||

| Three-level (Wells original) |

Low risk: <2 Moderate risk: 2–6 High risk: ≥7 |

Three-level (Geneva revised) |

Low risk: 0–3 Moderate risk: 4–10 High risk: ≥11 |

| Two-level (Wells) |

PE-unlikely: 0–4 PE-likely: ≥5 |

Two-level (Geneva) |

PE-unlikely: 0–5 PE-likely: ≥6 |

🧮 Wells Score

- The Wells Score is a clinical risk-stratification tool designed to estimate the probability of pulmonary embolism.

- It has been validated primarily in emergency department populations.

- ⚠️Although some evidence suggests applicability in hospitalized patients, its use in this setting should be approached with caution.

- Interpretation *: