Dec 19, 2021 via Shahriar Lahouti

CONTENTS

- Preface

- Terminology

- Clinical Presentation

- Complications

- Investigations

- Urine analysis

- Cultures

- Imaging

- Blood work

- Diagnostic considerations

- Management

- Special situations

- Further going

- References

Preface

Urinary tract infections (UTI) are a heterogeneous group of disorders, involving infection of all or part of the urinary tract, and are defined by bacteria in the urine with a wide spectrum of clinical symptoms ranging from lower urinary tract symptoms to life-threatening septic shock. In this post complicated urinary tract infection is explored.

Terminology

Uncomplicated versus complicated UTIs

This classification is not specifically anatomic or physiologic, but more generally attempts to discern which patients are most likely to recover uneventfully with therapy (uncomplicated) versus patients who are at an increased risk of treatment failure (complicated). Complicated UTI (in this post) is defined, based on extent of infection and severity.

Acute complicated UTI is used here to refer to an acute UTI with any of the following features which suggest that infection extends beyond the bladder

- Signs/symptoms of systemic illness (see below)

- Flank pain, costovertebral angle tenderness suggesting pyelonephritis

- Pelvic or perineal pain in men which can suggest accompanying prostatitis

By this definition, pyelonephritis is a complicated UTI regardless of the patient characteristics. In the absence of any above symptoms, UTI is considered acute simple cystitis.

Clinical presentation

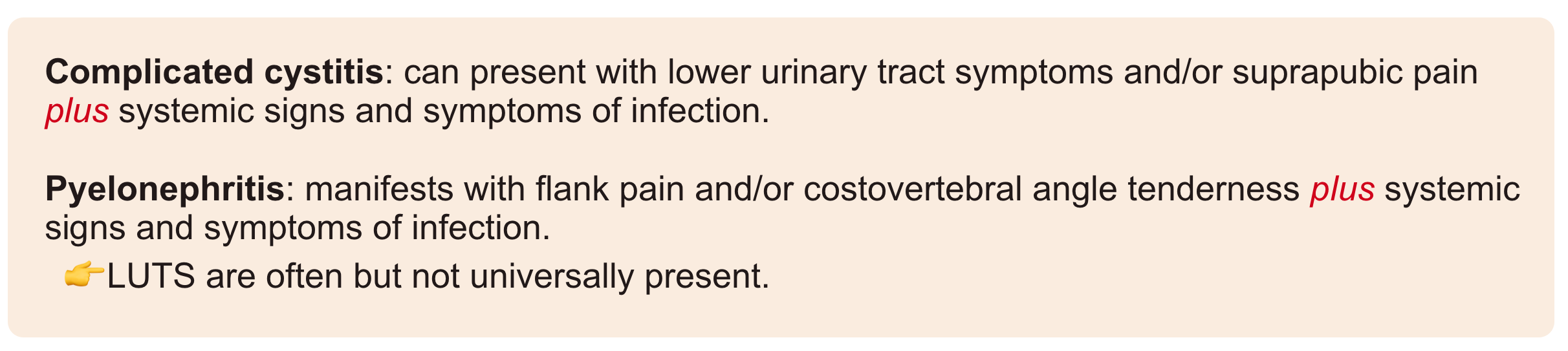

Acute complicated UTI is defined as infection beyond the bladder. Generally, clinical signs and symptoms of UTI can be classified into two groups:

Localizing signs and symptoms 1

- Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS): dysuria, frequency, gross hematuria or new or worsening urgency or urinary incontinence.

- Suprapubic pain suggests cystitis

- Pelvic or perineal pain in male suggesting prostatitis

- Flank pain, costovertebral angle tenderness may suggest pyelonephritis.

👉Not all patients with acute complicated UTI present with clear symptoms localizing to the urinary tract. As an example, patients with spinal cord injury and neurogenic bladder can present with autonomic dysreflexia and increased spasticity.

Systemic signs and symptoms 1

- Fever (> 37.7ºC)

- Rigors

- Nausea/vomiting

- Misleading signs and symptoms!

- Marked fatigue or malaise beyond baseline

- Mental status change (clear-cut delirium)

- Determining whether a change in behavior or mental status is present can be particularly challenging, (due to interobserver variability). Among elderly fortunately, dysuria can be reliably identified. The presence of dysuria appears to be among strongest predictors of bacteriuria plus pyuria in nursing home residents, and new dysuria is the most helpful clinical finding in identifying UTI in older adults.

- Falls are often considered a reason to test a nursing home resident for UTI, but the association of falls and UTI is controversial. In several studies, no association between falls and the presence of bacteriuria plus pyuria were found.

👉While there is no single clinical symptom, sign or lab test that is accurate enough to rule in or rule out a UTI, certain symptoms in combination greatly increase the likelihood of a UTI.

👉Urine turbidity, sediment color, and odor do not reliably correlate with the presence of infection and are not in themselves symptoms of UTI; they are, however, associated with antibiotic overprescribing!

Complications

Acute complicated UTIs can cause

- Bacteremia, sepsis (urosepsis)

- Multiorgan failure

- Acute kidney injury

- Development of pyelonephritis can be associated with

- Renal corticomedullary abscess

- Perinephric abscess

- Emphysematous pyelonephritis

- Papillary necrosis

Risk factors

Risk factors associated with complications are frequently reported as:

- Diabetes

- Elderly

- Urinary tract obstruction

- Features that should raise suspicion for urinary tract obstruction include a decline in the renal function below baseline or a decline in urine output.

- Recent urinary tract instrumentation

- Other urinary tract abnormalities

Investigation

By enlarge urine analysis is sensitive, but not specific. The urinalysis has a negative predictive value for growth of bacteria in urine culture approaching 100%.

👉Abnormal urinalysis is common among healthy elderly patients due to colonization with bacteria (asymptomatic bacteriuria) 1 (see below). Hence, abnormal urine analysis should always be interpreted in appropriate clinical context!

-

Modes of urine collection 2

-

Clean-catch void is most common. The peri-urethral area must be cleaned with a sterile wipe and urine caught mid-stream. Foreskin should be retracted or labia separated to prevent contamination.

-

Urethral catheter via single intermittent or indwelling. This method is invasive and can introduce bacteria to the urinary tract.

-

Suprapubic catheters are even more invasive and are thus reserved for situations in which urethral catheterization is not possible.

-

- Leukocyte esterase urine dipstick test has an overall sensitivity of 62% to 98% and a specificity of 55% to 96% for identifying infection

- Nitrate: the urine nitrite reaction has a low sensitivity (~50%), so it is not always useful as a screening examination because a negative result does not exclude the diagnosis of UTI

- Nitrate are generated by gram-negative enteric pathogens, but not gram-positives 3.

- In urinary tract infection with gram-positives, nitrites are detected only rarely (~5% of cases).

- In urinary tract infection with gram-negatives, nitrites are commonly detected (~40% of cases).

-

The urine nitrite reaction has a very high specificity (>90%), and a positive result is very useful in confirming the diagnosis of a UTI caused by bacteria that convert nitrates to nitrite (e.g. coliform bacteria, including E. coli). Enterococcus, Pseudomonas, and Acinetobacter species do not convert nitrates to nitrites in the urine and therefore are not detected by the nitrite test.

- Nitrate are generated by gram-negative enteric pathogens, but not gram-positives 3.

- The combination of leukocyte esterase and nitrite positivity suggests a UTI with 98%-100% specificity, although sensitivity has been found to be 35%-84% 4 .

-

Microscopic analysis: Direct visualization under a microscope to count RBCs, WBCs, bacteria, and epithelial cells.

-

Significant presence of epithelial cells suggests a contaminated sample.

-

Pyuria (WBCs) and hematuria (RBCs) suggest an inflammatory response within the urinary tract, but bleeding from other causes such as vaginal bleeding or bladder/renal masses should be considered if RBCs are predominant.

-

Pyuria (>10 WBCs per high powered field on microscopy or positive leukocyte esterase1) is present in almost all patients with UTI.

- WBC casts, in particular suggest renal origin of pyuria.

-

WBC >10 per mm3 correlates with urine culture bacterial concentrations of 105 cfu/mL, meeting the culture definition of UTI.

- Note that pyuria and bacteriuria may occasionally be absent, if the infection does not communicate with the collecting system or if the collecting system is obstructed.

- The presence of bacteriuria (>105 CFU) w/wo pyuria in the absence of any attributing symptoms of UTI, is called asymptomatic bacteriuria and generally does not warrant treatment in nonpregnant patients who are not undergoing urologic surgery.

-

-

The definition of a positive urine culture depends on the mode of collection.

- For voided samples, a count of 105 cfu/mL of a single organism is accepted as diagnostic of a bacterial UTI. Some data support a threshold of 102 cfu/mL in symptomatic patients if the organism grown is a known urine pathogen.

- Catheterized specimens: 102 cfu/mL in symptomatic patients.

- Suprapubic specimens: Considered positive with any amount of bacteria.

Blood culture

The utility of blood cultures has been questioned, as they will generally match the urine culture results. Obtaining blood culture may be most useful in critically ill patients who initially may appear to have urosepsis; but later are diagnosed with something else (e.g. endocarditis or ascending cholangitis).

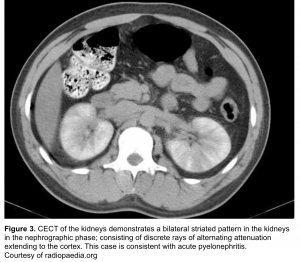

Most patients with acute complicated UTI do not warrant imaging studies for diagnosis or management. The main goals for imaging are 5:

- If alternative dx is suspected such as nephrolithiasis.

- Identify conditions that may delay response to antibiotic treatment such as obstruction.

- Recognizing complication of infection, such as a renal or perinephric abscess

- Imaging should be obtained urgently in patients with sepsis or septic shock to identify any evidence of obstruction or abscess that requires urgent source control 7 .

Indications for Imaging

- Severely ill patients

- Persistent clinical symptoms despite 48 to 72 hours of appropriate antimicrobial therapy

- Suspected urinary tract obstruction (eg, if the renal function has declined below baseline or if there is a precipitous decline in the urinary output).

- Recurrent symptoms within a few weeks of treatment

CT without contrast has become the standard radiographic study for demonstrating calculi, gas-forming infections, hemorrhage, obstruction, and abscesses.

- Direct finding which may suggest pyelonephritis on non-contrast may include

- Affected parts of the kidney may appear edematous, i.e. swollen and of lower attenuation.

- Perinephric stranding may suggest pyelonephritis.

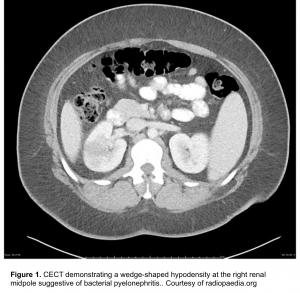

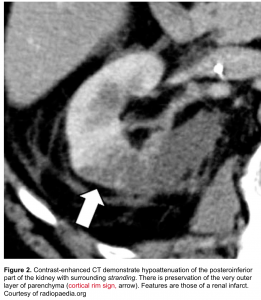

Contrast is needed to demonstrate alterations in renal perfusion. CT findings of pyelonephritis include 6

- One or more focal wedge-like regions will appear swollen and demonstrate reduced enhancement due to ischemia induced by marked neutrophilic infiltration and edema (figure 1).

- The periphery of the cortex is also affected, helpful in distinguishing acute pyelonephritis from a renal infarct (which tends to spare the periphery; the so-called rim sign. figure 2).

- Striated nephrogram (If imaged during the excretory phase)

The CT can be normal in patients with mild infection. Resolution of radiographic hypodensities may lag behind clinical improvement by up to three months.

Renal ultrasound is appropriate in patients for whom exposure to contrast or radiation is undesirable, however it is insensitive to the changes of acute pyelonephritis, with most patients having ‘normal’ scans. Abnormalities are identified in only ~25% of cases 14. Possible features include:

- Particulate matter/debris in the collecting system

- Reduced areas of cortical vascularity by using power Doppler

- gas bubbles (emphysematous pyelonephritis)

- abnormal echogenicity of the renal parenchyma

- Focal/segmental hypoechoic regions (in edema) or hyperechoic regions (in hemorrhage)

- Mass-like change

👉Ultrasound is, however, useful in assessing for local complications such as hydronephrosis, renal abscess formation, perinephric collections and thus may guide management.

Blood works

- Cell counts, renal function are warranted in complicated UTIs.

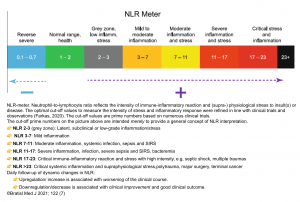

- NLR

- The NLR is the ratio of neutrophils/lymphocytes.

- Physiologic stress increases neutrophil count and reduces lymphocyte count, causing the NLR to increase. This likely involves some combination of endogenous cortisol and catecholamine secretion. Sepsis stimulates lymphocyte apoptosis, so this may cause especially dramatic elevation of the NLR compared to other forms of physiologic stress 8.

- NLR elevates rapidly following physiologic stress (within <6 hours), often earlier than other indices such as the white blood cell count.

- Utility: NLR may be helpful in sorting out patients with systemic illness versus patients with milder illness

- Rough interpretation of the NLR

- ~ 1-3 is normal.

- ~ 3-7 suggests mild stress (e.g. uncomplicated appendicitis).

- ~ 7-11 suggests moderate stress (e.g. most critically ill patients).

- ~ 11-17 suggests severe stress (e.g. sepsis with gram negative bacteremia).

- Use of NLR in patients with suspected septic shock:

- NLR <3

- This should cast some doubt on the diagnosis of sepsis (>95% of septic patients will have an NLR above 3).

- One driver of NLR elevation is cortisol. Therefore, an unexpectedly low NLR in the context of definite septic shock may suggest the possibility of adrenal insufficiency.

- NLR >10-11

- Higher NLR values support the diagnosis of septic shock.

- Pitfalls of the NLR

- Exogenous steroid may increase the NLR.

- Active hematologic disorder may affect the NLR (e.g. leukemia, cytotoxic chemotherapy, granulocyte colony stimulating factor).

Inflammatory markers

- Procalcitonin is an index of inflammation, which is especially sensitive to typical bacterial pathogens (esp. gram negative bacilli).

- It is elevated most strongly by interleukin-1 beta, tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-6. Alternatively viral infections tend to elevate levels of interferon gamma, which inhibits the production of tumor necrosis alpha and thereby decreases the procalcitonin level.

- Procalcitonin is validated predominantly as an antibiotic-discontinuation tool among medical ICU patients (with low levels supporting a decision to discontinue antibiotics). RCTs have demonstrated that procalcitonin use reduces antibiotic exposure and might even decrease mortality 9.

- Procalcitonin is not validated as a trigger for making the initial diagnosis of sepsis, nor as a trigger for the initiation of antibiotics.

- False-negatives caused by:

- Neutropenia, severe immunosuppression.

- Localized infections that don’t cause systemic inflammation.

- Procalcitonin may remain low early on during infection. Procalcitonin usually elevates within 4-6 hours, peaking around 12-48 hours) 10.

- Atypical bacteria often don’t elevate procalcitonin (e.g., mycoplasma pneumoniae).

- False-positives caused by:

- Renal failure

- Pancreatitis, ischemic bowel, surgery, trauma, burns, and cardiac arrest.

- Some elevation can occur with fungal, viral infections.

- Some rheumatologist diseases (e.g. Adult Still’s disease, granulomatosis with polyangiitis).

- Some cancers (e.g. small-cell lung cancer, medullary thyroid carcinoma).

- How to use procalcitonin in suspected septic shock

- Procalcitonin should be measured if all of the following criteria are met:

- Patient is already started on antibiotics, based on a clinical suspicion for sepsis.

- Patient isn’t severely immunocompromised.

- Patient has not definitively been diagnosed with sepsis.

- Procalcitonin should be measured if all of the following criteria are met:

- Interpretation of procalcitonin in suspected septic shock:

- Procalcitonin >0.5 ug/ml is consistent with a diagnosis of septic shock. Extremely high values may suggest a gram negative infection.

- Procalcitonin <0.5 ug/ml casts some doubt on the diagnosis of septic shock:

- Consider the possibility of noninfectious septic mimics (e.g. thyroid storm).

- If doubt remains, check a procalcitonin the next day (procalcitonin may take a day to elevate).

- CRP elevates largely in response to interleukin 6, interleukin-1 beta and tumor necrosis factor alpha.Compared to procalcitonin, CRP is less specific for bacterial infection. Rather, CRP functions more as an index of systemic inflammation.

- Procalcitonin is generally preferred over CRP for the evaluation of bacterial sepsis 11.

- However CRP is not affected by renal failure or neutropenia, so CRP might be superior to procalcitonin in those situations.

- Limitations of CRP for diagnosis of severe systemic inflammation

- Like procalcitonin, CRP rises within ~6 hours of systemic inflammation. CRP may remain low at the time of admission, subsequently elevating over the next day 12.

- CRP is synthesized by the liver, causing it to be falsely low in fulminant hepatic failure (but not in patients with cirrhosis).

- CRP can be reduced by steroid administration

- How to interpret CRP in patients with suspected septic shock

- Low CRP (<10-20 mg/L, or <1-2 mg/dL)

- This does not exclude infection, but it casts doubt on the diagnosis of severe systemic infection.

- CRP rises over time, beginning within ~6 hours of an acute event. If the CRP remains low the following day, that further supports an absence of infection.

- Low CRP (<10-20 mg/L, or <1-2 mg/dL)

- Markedly elevated CRP (>100 mg/L, or >10 mg/dL)

- This is consistent with septic shock, but not diagnostic of it.

- Causes of CRP >100 mg/L include the following 13:

- Severe bacterial, fungal, or viral infection.

- Pancreatitis (with or without superinfection).

- Lupus flair (usually with vasculitis or serositis).

- Severe trauma or burns, cardiac surgery.

- Serotonin syndrome.

- After cardiac arrest.

Diagnostic considerations

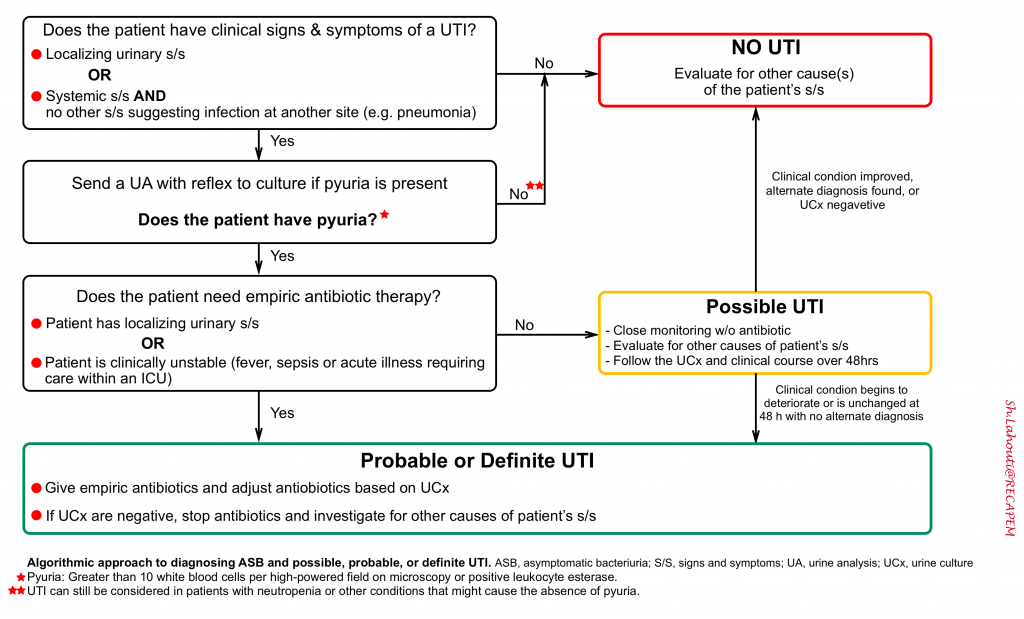

In patients with signs and symptoms of complicated UTI (see above), urine analysis will inform the diagnosis. The algorithmic approach to diagnosing ASB and “possible, probable, or definite” UTI, is shown below. UTIs are defined by 3 components 1:

- First, the patient should have clinical signs and symptoms suggesting infection of the urinary tract.

- In older adults, accepted clinical criteria include dysuria alone or fever accompanied by frequency, suprapubic pain, gross hematuria, costovertebral angle tenderness, or new or worsening urgency or urinary incontinence.

- For those with an indwelling urinary catheter or who had 1 removed in the previous 48 hours, fever, rigors, or delirium alone (all of which are nonspecific); or new costovertebral tenderness, may herald a CAUTI.

- Second, laboratory evidence should demonstrate both pyuria and bacteriuria.

- Laboratory testing is primarily useful for excluding UTIs.

- Pyuria is sensitive but not specific for UTI, particularly among catheterized patients in whom its presence is ubiquitous. Reliance on pyuria alone for the diagnosis of UTI would lead to widespread antibiotic overtreatment, particularly because pyuria accompanies ASB. In this regard, the clinical utility of the urinalysis for diagnosing UTI is akin to that of the D-dimer for the diagnosis of a pulmonary embolism.

- Third, a thorough search for other causes to explain the patient’s symptoms and laboratory findings are unrevealing.

-

This is particularly relevant for older adults, in whom symptoms attributed to UTI are often not specific to the urinary tract (e.g. fever, lethargy and confusion) and may belie infection at another site (e.g. pneumonia), systemic infection (e.g. influenza), or another cause entirely (e.g. heart failure exacerbation).

-

Management

Indication for Hospitalization

The decision to admit patients with acute complicated UTI should be individualized. Indications for admission include:

- Septic or otherwise critically ill (it’s clear!)

- Suspected urinary tract obstruction

- Persistently high fever (e.g. >38.4°C)

- Persistent pain

- Marked debility

- Inability to maintain oral hydration or take oral medications

- Non-adherent patients

Outpatient management is acceptable for patients with acute complicated UTI of mild to moderate severity who can be stabilized, if necessary, with rehydration and antimicrobials in an outpatient facility or the emergency department and discharged on oral antimicrobials with close follow-up.

- Many patients can be managed in the outpatient setting. As an example, in a study of 44 patients with pyelonephritis but no major comorbidities, a 12h observation period with parenteral antimicrobial therapy in the ED followed by completion of outpatient oral antimicrobials was effective management for 97% of patients.

Antibiotics

General principles

Several helpful considerations can guide physicians to choose appropriate empiric antibiotic for patients with acute complicated UTIs. One should consider the following issues:

- The common uropathogens

- Antibiogram

- Indications for broad spectrum antibiotic coverage

Common uropathogens

- Initial antibiotic coverage should be broad enough to cover most common uropathogens.

- In a population-based analysis of a total of 4887 of subjects who were diagnosed with pyelonephritis including those who had received an inpatient or culture-confirmed outpatient diagnosis of acute pyelonephritis, the most common uropathogens isolated at the time of diagnosis were reported as:

- Escherichia coli: The vast majority of pyelonephritis reported to be due to gram negative rods (E.coli).

- Other reported organisms in order of frequency were:

- Klebsiella species

- Enterococcus species (most common gram positive species)

- Staphylococcus saprophyticus

- Citerobacter species

- Enterobacter species

- Proteus species

- Pseudomonas species

- Staphylococcus aureus

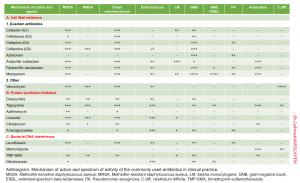

Antibiogram

The following table provides mechanisms of action and spectrum of microbial coverage for commonly used antibiotics in clinical practice.

Indications for broad spectrum antibiotic

Empiric antimicrobial therapy should be initiated promptly (if indicated). Broad coverage may be considered in the presence of following conditions:

- Severity of illness: for example critically ill patients who require ICU admission (e.g. septic shock) will require a broad spectrum coverage.

- Have a lower threshold to cover empirically for MDR pathogens in patients with more severe disease.

- Specific host factors: For example patients with severe illness and suspected obstruction will also require broad spectrum coverage.

- Response to current antibiotic treatment: If the patient is getting worse on current antibiotic regimen, then it may be reasonable to switch to a broad spectrum antibiotic while awaiting the culture results.

- Risk factors for resistant pathogens: Consider the following factors

- Previous antimicrobial use

- Results of recent urine cultures

- Local community resistance (if known): for example over-use of fluoroquinolones in some communities has led to increasing antibiotic resistance (e.g. ciprofloxacin resistance among E. coli is reaching 15%).

- Multi-drug resistant pathogens: In particular an MDR isolate which is non-susceptible to at least one agent in three or more antimicrobial classes; this includes ESBL-producing isolates. Risk factors for MDR gram negative infection include:

- An MDR gram negative urinary isolate.

- In-patient stay at health care facility (e.g. hospital, nursing home, long-term acute care facility).

- Use of fluroquinolones, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or broad-spectrum beta-lactam (this includes a single antimicrobial dose given for prophylaxis prior to prostate procedures).

- Travel to part of the world with high rates of MDR organisms.

Empiric antimicrobial therapy

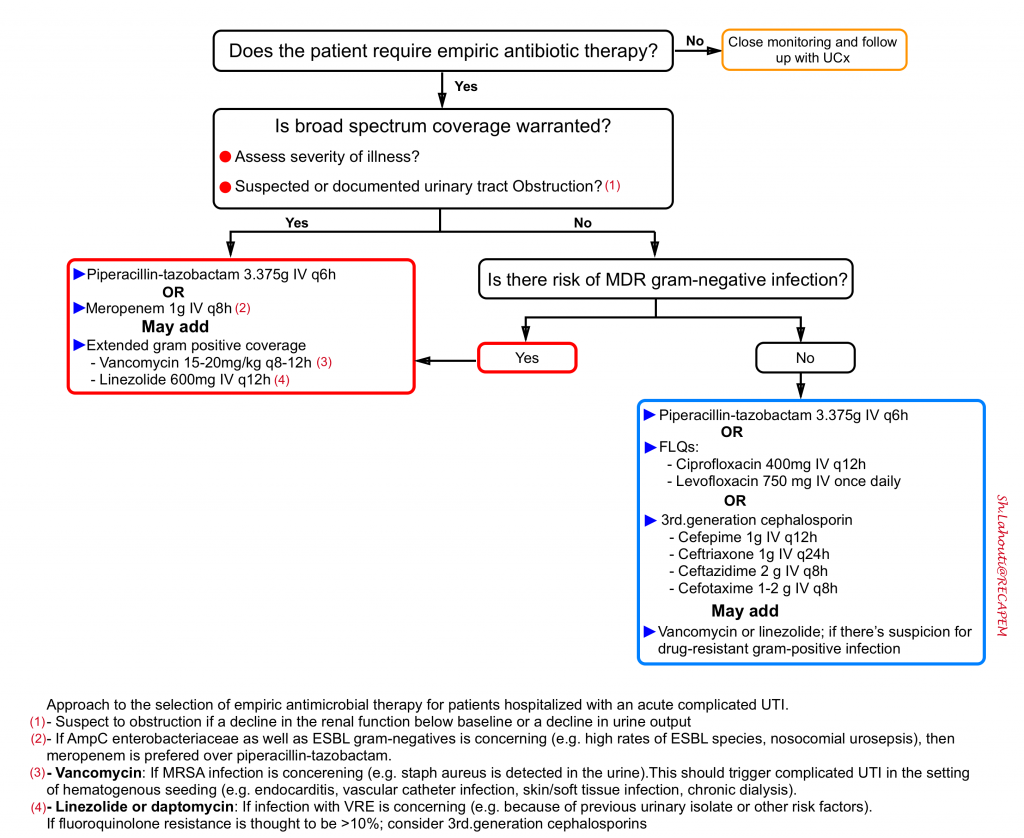

The approach to empiric therapy of acute complicated UTI (see the algorithm below) depends on the severity of illness, the risk factors for resistant pathogens, and specific host factors. The choice among the options presented for each population depends on susceptibility of prior urinary isolates, patient circumstances (such as allergy or expected tolerability, history of prior antimicrobial use), local community resistance prevalence of Enterobacteriaceae (if known), and drug toxicity, interactions, availability, and cost.

Piperacillin-tazobactam

Strengths

- Excellent gram-negative coverage, including pseudomonas.

- Coverage of community-acquired gram-positives (e.g., enterococcus faecalis and Staph saprophyticus).

- Adequate coverage for AmpC enterobacteriaceae (piperacillin-tazobactam not be ideal for them, but emerging evidence suggests that it is adequate) 15.

Weaknesses

- The main limitation of piperacillin-tazobactam is that it’s not optimal for extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) gram-negatives. Some reports indicate that ESBL are being seen increasingly in the community, particularly in certain geographic locales. Fortunately, piperacillin-tazobactam may often be adequate for ESBL species, especially urinary tract infection with ESBL E. Coli 16.

- Piperacillin is generally safe in patients with a history of penicillin allergy, but in some cases this may remain a concern.

Meropenem

- Strengths:

- Excellent gram-negative coverage, including pseudomonas.

- Coverage of community-acquired gram-positives (e.g. enterococcus faecalis and Staph saprophyticus).

- Excellent coverage for AmpC enterobacteriaceae as well as ESBL gram-negatives. This can make meropenem a good choice for nosocomial urosepsis, or in contexts with high rates of ESBL species.

- Unlike most beta-lactams, carbapenems decrease lipopolysaccharide release from gram-negative bacteria, which could give them an advantage in the treatment of gram-negative septic shock.

- Allergy to meropenem does not exist. So meropenem can be confidently used in patients with a history of numerous antibiotic allergies (including anaphylaxis to penicillins or cephalosporins).

- Weaknesses:

- For most patients from the community, meropenem is unnecessarily broad!

Fluoroquinolones

- Strengths

- Adequate gram-negative coverage including pseudomonas (esp. ciprofloxacin)

- Weakness

- Not effective against AmpC enterobacteriaceae as well as ESBL gram-negatives.

- Inadequate gram-positive coverage esp. inffective against enterococcus.

- Increasing antibiotic resistance (e.g. >25% resistance of E. coli to ciprofloxacin in many locations).

- Fluoroquinolones induce the emergence of multi-drug resistant bacteria to a much greater extent than most antibiotics

- Associated with several adverse effects including delirium, persistent neurologic abnormalities 17, C. difficile-associated disease, tendinopathy and possibly aortic aneurysm

Extended coverage for gram-positive pathogens

- If gram-positive cocci shown on gram stain; the primary concern will be entrococci.

- Other less common pathogens could be staphylococcus saprophyticus, staphylococcus aureus (the aformentioned antibiotics usually cover these effectively). If staph aureus is detected in the urine this should trigger suspicion of some other infectious process (e.g. endocarditis with hematogenous seeding of the kidneys).

- Methicillin-resistant staph aureus (MRSA) is an extremely uncommon cause of community-acquired urosepsis (~0.25%).

- If Enterococcus species or MRSA are suspected (e.g. because of prior urinary isolates or gram-positive cocci on a current urine Gram stain); linezolid for vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) or vancomycin for MRSA can be added.

Directed antimicrobial therapy and duration

- Results of urine culture and susceptibility testing should be used to confirm that the chosen empiric regimen is active and to tailor the regimen, if appropriate. In many cases, broad-spectrum empiric regimens can be replaced by a more narrow-spectrum agent.

- Patients who were initially treated with a parenteral regimen can be switched to an oral agent once symptoms have improved, as long as culture and susceptibility testing allow.

- Total duration of antimicrobial therapy generally ranges from 5 to 14 days, depending on the rapidity of clinical response and the antimicrobial chosen to complete the course.

- Longer durations may be warranted in patients who have a nidus of infection (such as a nonobstructing stone) that cannot be removed

Special situations

Asymptomatic bacteriuria

It is reasonable to review asymptomatic bacteriuria here, since unnecessary antibiotic treatment for abnormal urine analysis is a growing concern!

Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) is defined as the presence of bacteria in the urine, with or without pyuria, in the absence of clinical symptoms indicating a UTI 1 .

- ASB is common in older adults; in one study of nursing home residents, 25% to 50% of subjects had bacteriuria at any give time.

- Keep in mind that urine culture does not distinguish between UTI and ASB.

- Urine cultures should not be obtained in older adults unless clinical symptoms suggest a UTI and the accompanying urinalysis demonstrates pyuria (or the patient is neutropenic). Inappropriate ordering of urine cultures is harmful because detection of bacteriuria may lead to inappropriate antibiotic therapy, particularly when the patient has a peripheral leukocytosis or when the urine is colonized by a typical or multidrug-resistant uropathogen.

- Older adults with ASB do not experience increases in mortality.

- Antibiotics administered for ASB do not reduce the rates of subsequent complication and perversely, may increase the risk for a subsequent symptomatic UTI. Furthermore, unnecessary antibiotic treatment is associated with acquisition of drug-resistant pathogens, C difficile infection, and other drug-related adverse events.

When to treat ASB?

ASB should only be treated in pregnant women or immediately before a urologic procedure likely to involve mucosal injury.

Catheter associated UTI

Catheter associated UTI (CAUTI) refers to development of urinary tract infection in a patient who is catheterized or has had a urinary catheter removed within <48 hours 1 . The Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) definition of CAUTI requires all of the following components:

- Culture growth of at least 1,000 CFU per ml of a uropathological bacteria.

- Note: Candiduria doesn’t qualify for the diagnosis of CAUTI.

- Symptoms or signs of a urinary tract infection (e.g. fever, costovertebral angle tenderness, hypotension).

- No alternative explanation of these symptoms, despite adequate evaluation.

- Patient is catheterized or has had a urinary catheter removed within <48 hours.

Keep in mind that; CAUTI is a diagnosis of exclusion.

- Positive urinary culture by itself does not indicate CAUTI (and most often such patients won’t have a CAUTI).

- Presence of pyuria is not helpful. As sterile irritation of the bladder by the urinary catheter can cause pyuria.

- Do not assume that the combination of a fever and positive urinalysis means that there is a CAUTI.

- Note that presence of signs of bladder irritation (e.g. frequency, dysuria, urgency) for a patient with urinary catheter is non-specific, since these can be caused by direct irritation from the catheter.However, for a patient whose catheter has been removed, these symptoms should be considered as potential symptoms of infection.

- Bladder ultrasonography has paramount importance in diagnosis of CAUTI.

- The finding of a distended bladder indicates dysfunction of the Foley catheter. This indicates a real risk of cystitis, pyelonephritis, septic shock, and obstructive renal failure.

- A non-distended bladder indicates normal function of the Foley catheter. In the context of a patient without neutropenia, this makes invasive bacterial infection distinctly unlikely.

When to start antibiotics?

- It is unclear exactly when antibiotics should be started during the diagnostic evaluation for CAUTI.

- For patients with clinical signs of septic shock or neutropenic fever, antibiotic initiation should not be delayed.

- For patients with an isolated fever, antibiotics should generally be withheld pending additional investigation (fever isn’t an indication for antibiotics!).

Further going

References

1. Cortes-Penfield NW, Trautner BW, Jump RLP. Urinary Tract Infection and Asymptomatic Bacteriuria in Older Adults. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2017 Dec;31(4):673-688. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2017.07.002. PMID: 29079155; PMCID: PMC5802407.

2. Queremel Milani DA, Jialal I. Urinalysis. [Updated 2021 May 9]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557685/

3. Holloway J, Joshi N, O’Bryan T. Positive urine nitrite test: an accurate predictor of absence of pure enterococcal bacteriuria. South Med J. 2000 Jul;93(7):681-2. PMID: 10923955.

4. Lane DR, Takhar SS. Diagnosis and management of urinary tract infection and pyelonephritis. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2011 Aug;29(3):539-52. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2011.04.001. PMID: 21782073.

5. Craig WD, Wagner BJ, Travis MD. Pyelonephritis: radiologic-pathologic review. Radiographics. 2008 Jan-Feb;28(1):255-77; quiz 327-8. doi: 10.1148/rg.281075171. PMID: 18203942.

6. Das CJ, Ahmad Z, Sharma S, Gupta AK. Multimodality imaging of renal inflammatory lesions. World J Radiol. 2014;6(11):865-873. doi:10.4329/wjr.v6.i11.865

7. Reyner K, Heffner AC, Karvetski CH. Urinary obstruction is an important complicating factor in patients with septic shock due to urinary infection. Am J Emerg Med. 2016 Apr;34(4):694-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.12.068. Epub 2015 Dec 23. PMID: 26905806.

8. Zahorec R. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, past, present and future perspectives. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2021;122(7):474-488. doi: 10.4149/BLL_2021_078. PMID: 34161115.

9. Dugar S, Choudhary C, Duggal A. Sepsis and septic shock: Guideline-based management. Cleve Clin J Med. 2020 Jan;87(1):53-64. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.87a.18143. Epub 2020 Jan 2. PMID: 31990655

10. Hohn A, Heising B, Schütte JK, Schroeder O, Schröder S. Procalcitonin-guided antibiotic treatment in critically ill patients. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2017 Feb;402(1):1-13. doi: 10.1007/s00423-016-1458-4. Epub 2016 Jun 10. PMID: 27283067

11. Nargis W, Ibrahim M, Ahamed BU. Procalcitonin versus C-reactive protein: Usefulness as biomarker of sepsis in ICU patient. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2014 Jul;4(3):195-9. doi: 10.4103/2229-5151.141356. PMID: 25337480; PMCID: PMC4200544.

12. Lelubre C, Anselin S, Zouaoui Boudjeltia K, Biston P, Piagnerelli M. Interpretation of C-reactive protein concentrations in critically ill patients. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:124021. doi: 10.1155/2013/124021. Epub 2013 Oct 28. PMID: 24286072; PMCID: PMC3826426

13. Ho KM, Lipman J. An update on C-reactive protein for intensivists. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2009 Mar;37(2):234-41. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0903700217. PMID: 19400486

14. Craig WD, Wagner BJ, Travis MD. Pyelonephritis: radiologic-pathologic review. Radiographics. 2008 Jan-Feb;28(1):255-77; quiz 327-8. doi: 10.1148/rg.281075171. PMID: 18203942.

15. McKamey L, Venugopalan V, Cherabuddi K, Borgert S, Voils S, Shah K, Klinker KP. Assessing antimicrobial stewardship initiatives: Clinical evaluation of cefepime or piperacillin/tazobactam in patients with bloodstream infections secondary to AmpC-producing organisms. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2018 Nov;52(5):719-723. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.08.007. Epub 2018 Aug 17. PMID: 30125680.

16. Rodríguez-Baño J, Navarro MD, Retamar P, Picón E, Pascual Á; Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamases–Red Española de Investigación en Patología Infecciosa/Grupo de Estudio de Infección Hospitalaria Group. β-Lactam/β-lactam inhibitor combinations for the treatment of bacteremia due to extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli: a post hoc analysis of prospective cohorts. Clin Infect Dis. 2012 Jan 15;54(2):167-74. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir790. Epub 2011 Nov 4. PMID: 22057701.

17. Tandan M, Cormican M, Vellinga A. Adverse events of fluoroquinolones vs. other antimicrobials prescribed in primary care: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2018 Nov;52(5):529-540. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.04.014. Epub 2018 Apr 25. PMID: 29702230

Add comment