Dec 23, 2021 via Shahriar Lahouti

CONTENTS

- Preface

- Etiology

- Risk factors

- Hypoglycemic agents

- Symptoms

- Complications

- Diagnosis

- Investigations

- Approach to treatment

- Disposition

- Prevention of hypoglycemia in critically ill patients

- Further going

- References

Preface

Severe hypoglycemia if prolonged can lead to permanent brain damage. Hence, rapid identification and correction of (suspected) hypoglycemia is critically important. In this post, diagnosis and treatment of hypoglycemia in adult patients is discussed.

Etiology

In diabetic patients, most hypoglycemic episodes requiring emergency care (60% in one study) are related to medication. Infection and worsening kidney function are other common causes of hypoglycemia in diabetic patients.

- People with type 1 diabetes are more commonly affected by hypoglycemia than people with type 2 diabetes, including the spectrum from asymptomatic hypoglycemia to severe hypoglycemic events 3.

In non-diabetic patients, the most common causes include infection, liver disease, and malignancy.

Common causes of hypoglycemia include 1

- Insulin

- Accidental, suicidal, iatrogenic, factitious.

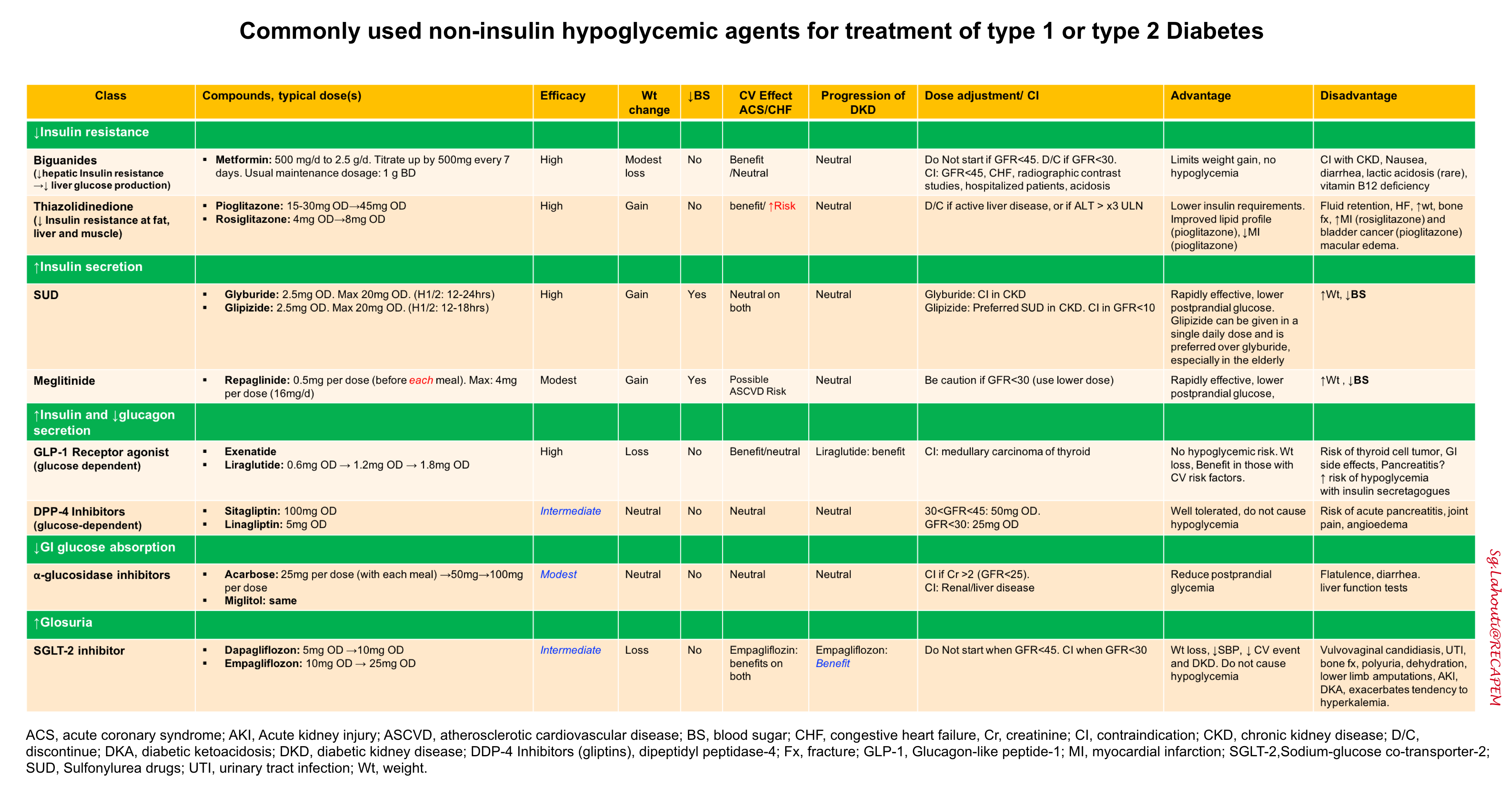

- Drugs that increase insulin secretion

- Sulfonylureas (glimepiride, glipizide, especially glyburide).

- Meglitinides (repaglinide, nateglinide).

- Pentamidine.

- Other mechanisms (evidence for many of these drugs is questionable)

- Diabetes medications not listed above (e.g. SGLT-2 inhibitors, metformin). These usually don’t cause hypoglycemia on their own, but may synergize with other risk factors.

- Fluoroquinolones (esp. gatifloxacin)

- Neurologic: Phenytoin, selegiline, valproate.

- Psychiatric: doxepin, haloperidol, fluoxetine, lithium.

- Nonselective beta-blockers (propranolol, nadolol).

- ACE inhibitors.

- NSAIDs (especially indomethacin).

- Sulfonamides.

- Quinine.

- Hydroxychloroquine, artemisinin antimalarials.

- Salicylate intoxication.

- Ethanol intoxication

- Specific diseases 2

- Adrenal insufficiency.

- Myxedema coma.

- Hepatic failure.

- Sepsis.

- Renal failure (usually not by itself; note that renal dysfunction may cause accumulation of many medications. Moreover the clearance of insulin is diminished).

- Insulinoma or various malignancies (e.g. mesenchymal tumors, hematologic malignancies).

- Status post gastric bypass surgery.

- Malignancy

- Pancreatitis

- Intake/use mismatch

- Starvation, anorexia nervosa.

- Exercise.

- Pregnancy/lactation.

- Alcohol binging

Risk factors

Several risk factors have been associated with development of severe hypoglycemia in patients treated with sulfonylureas or insulin 3

- Prior episode of severe hypoglycemia

- Current low A1C (<6.0%)

- Hypoglycemia unawareness

- Long duration of insulin therapy

- Autonomic neuropathy

- Chronic kidney disease

- Low economic status, food insecurity

- Low health literacy

- Preschool-aged children unable to detect and/or treat mild hypoglycemia on their own

- Adolescence

- Pregnancy

- Elderly

- Cognitive impairment

Hypoglycemic agents

Symptoms

Symptoms of hypoglycemia are either autonomic or neuroglycopenic in origin. However, they are non-specific for the diagnosis of hypoglycemia.

Autonomic symptoms (sympathetic activation): Autonomic symptoms are generated from the autonomic nervous system and thus are catecholamine driven

- Diaphoresis.

- Tremulousness, anxiety.

- Tachycardia, palpitations, increased blood pressure.

- Hunger.

Neuroglycopenic: These symptoms are generated because of the brain’s lack of glucose, causing decreased function. Brain dysfunction is usually the most obvious clinical finding.

- Confusion.

- Visual changes (blurred vision, diplopia).

- Slurred speech, dizziness.

- Seizures.

- Eventually: lethargy, stupor, coma.

Complications

- Prolonged severe hypoglycemia can cause permanent brain damage, similar to anoxic brain injury.

- Hypoglycemia is most dangerous among intubated and sedated patients, because mental status changes won’t be immediately evident.

- Generally, hypoglycemia is far more dangerous than hyperglycemia. When dosing insulin in an acute care setting, it’s always safer to leave the patient in a mildly hyperglycemic range.

Diagnosis

Defining hypoglycemia

There is no universally defined blood glucose level for hypoglycemia because patients may be symptomatic at different blood glucose levels. Patients with chronically high blood glucose may become symptomatically hypoglycemic with blood glucose higher than that in patients with normal baseline glucose levels.

Definitions of hypoglycemia vary. Overall, there are two main considerations:

- How low is the glucose? 4

- Moderate hypoglycemia: 40-70 mg/d.

- Severe hypoglycemia: <40 mg/dL.

- Is the patient symptomatic?

- Absence of symptoms is certainly reassuring.

- Presence of symptoms are worrisome, however signs and symptoms are non-specific.

Point-of-care glucose level

- This is the front-line test due to speed. It should be provided rapidly for any undifferentiated patient with altered mental status and/or focal neurologic deficit.

- Fingerstick glucose may be inaccurate in patients with poor perfusion. If fingerstick glucose is low, but you doubt whether it is an accurate measurement:

- Send blood to lab for glucose level.

- If patient is symptomatic or sedated, give IV dextrose immediately (without waiting for confirmatory lab results).

Laboratory measurement of glucose

- This is the gold-standard (e.g. it may be used to double-check fingerstick results in questionable cases).

- As noted above, treatment should not be delayed while awaiting a confirmatory laboratory result, unless the patient is awake and mentating normally without symptoms.

- Laboratory glucose measurement can be low if blood sits around for a long time before processing, or if there is severe leukocytosis.

Investigation

History is key.

- Medication history:

- The most common culprit is insulin or sulfonylurea misuse.

- Review new medications or dose changes.

- Changes in renal or hepatic function may cause drug accumulation.

- Adequacy of oral intake?

- Recent alcohol binge?

- Other features may suggest sepsis, chronic adrenal insufficiency, or hepatic failure.

Response to treatment

- Hypoglycemia is the most likely diagnosis if symptoms abate after glucose administration. However, if these symptoms persist, alternative diagnoses should be considered and investigated.

If cause remains unclear, obtain labs:

- Cortisol level to exclude adrenal insufficiency

- Generally a stressed, hypoglycemic patient should have somewhat elevated levels of cortisol. Low levels should alert to the possibility of adrenal insufficiency.

- When in doubt, an ACTH stimulation test should be performed to clarify.

- Liver function tests.

- Insulin level

- Insulin level > 3 micro-units/ml (21 pM) in context of hypoglycemia suggests pathologically excessive insulin levels. This may reflect either endogenous insulin synthesis or exogenous insulin administration.

- Unfortunately, some synthetic forms of insulin may not be detected by the assay (e.g. glargine).

- C-peptide level

- Measures only endogenous insulin production, allowing differentiation between endogenous over-production of insulin versus exogenous insulin administration.

- C-peptide level >0.2 nM (0.6 ng/ml) in the context of hypoglycemia suggests pathologically elevated insulin secretion by the pancreas.

- beta-hydroxybutyrate

- Elevated levels (above ~2.7 mM) argue against a hyperinsulinemic state (because insulin suppresses ketone production). Thus, elevated levels would suggest entities such as starvation, alcoholic ketoacidosis, or sepsis.

- Other diagnostic considerations

- Screening lab tests that should be sent should search for an etiology, such as infection. If the etiology is simply overmedication or underconsumption of nutrition, the workup can be very minimal.

- A screening creatinine level is recommended because patients may not be symptomatic from renal insufficiency.

Approach to treatment

Basic concepts

Following D50% administration, the blood glucose typically changes as

- Blood glucose is peaked by ~5 min and remains elevated for ~15min, then returns back to baseline after ~30min. These changes are due to volume of distribution of dextrose.

- This underscore frequent blood glucose monitoring (every 15-30min) following D50% infusion, since the blood glucose will inherently fall.

- Treatments should be titrated to achieve a safe glucose level (e.g. 100-200 mg/dL).

- Pushing the glucose too high can be counterproductive, as this can stimulate endogenous insulin release leading to rebound hypoglycemia.

Approach to critical patients

- Place patient on cardiac monitor and continuous pulse oximetry.

- Obtain point-of-care glucose.

- Secure intravenous (IV) or intraosseous (IO) access.

- Airway/Breathing/Circulation

-

Hypoglycemia is a rapidly reversible cause of impaired consciousness; intubation before glucose administration should be avoided

-

- For seizing or obtunded patients, administer dextrose.

- Dextrose bolus IV/IO

- Traditional treatment: Dextrose 50% 50 mL (25 g) IV/IO or

- Alternative treatment: Dextrose 10% 250 mL (25 g) IV/IO

- Advantages: D10W is less irritating to the veins than D50W. D10W may have a lower risk of overshoot hyperglycemia 5.

- Disadvantage: D10W takes slightly longer to give, so it may be less useful for patients with profound symptoms who need immediate treatment (e.g., seizure, coma).

- Dextrose infusion 6

- Either D5W or D10W are safe for peripheral infusion.

- The infusion rate depends on severity of hypoglycemia. A typical rate might be ~150 ml/hr D5W, or 75 ml/hr D10W. Titrate to effect, based on frequent glucose measurement.

- If the patient already has central access, you can give D20W or D50W centrally. However, placement of a central line for the sole purpose of treating hypoglycemia is generally unnecessary.

- Dextrose bolus IV/IO

- Octreotide: If the patient is taking a sulfonylurea, administer as:

- Load with 100 mcg IV once, then continue a maintenance dose of 50 mcg subcutaneously q6hr.

- Octreotide should be administered after dextrose bolus. Do not delay glucose correction to give octreotide.

- Rebound hypoglycemia can occur within 24 hours of stopping the octreotide, so patients should be monitored during this period.

- Glucagon- Useful or not?

- The traditional approach to severe hypoglycemia in a patient without IV access is to give 1 mg of glucagon intramuscularly. However, this is not a good idea for several reasons:

- Glucagon may not work, if the patient’s liver glycogen stores are depleted.

- Glucagon can stimulate vomiting, which may be particularly dangerous if the patient has altered mental status and cannot protect their airway.

- Even if the glucagon doesn’t cause vomiting, it may cause nausea that impairs the ability to feed the patient later on.

- Glucagon takes 10-15min to work, which seems like a fairly long delay for a patient with severe hypoglycemia.

- The traditional approach to severe hypoglycemia in a patient without IV access is to give 1 mg of glucagon intramuscularly. However, this is not a good idea for several reasons:

Mild hypoglycemia and able to tolerate ‘PO’

- If hypoglycemia is mild and the patient is able to take PO intake, provide oral carbohydrate (e.g. juice).

- For intubated patients with enteral access, this may be provided via orogastric tube.

- Avoid peripheral D50W if you don’t need it, because over time repeated doses can cause sclerosis of peripheral veins.

- To prevent recurrence, consider providing additional food that contains complex carbohydrates.

Disposition

- If a patient’s hypoglycemia can be attributed to inadequate oral (PO) intake or an inadvertent increase in short-acting or intermediate-acting insulin, the patient is alert, tolerating PO, and clinically stable, and glucose is stable on multiple rechecks, the patient may be discharged.

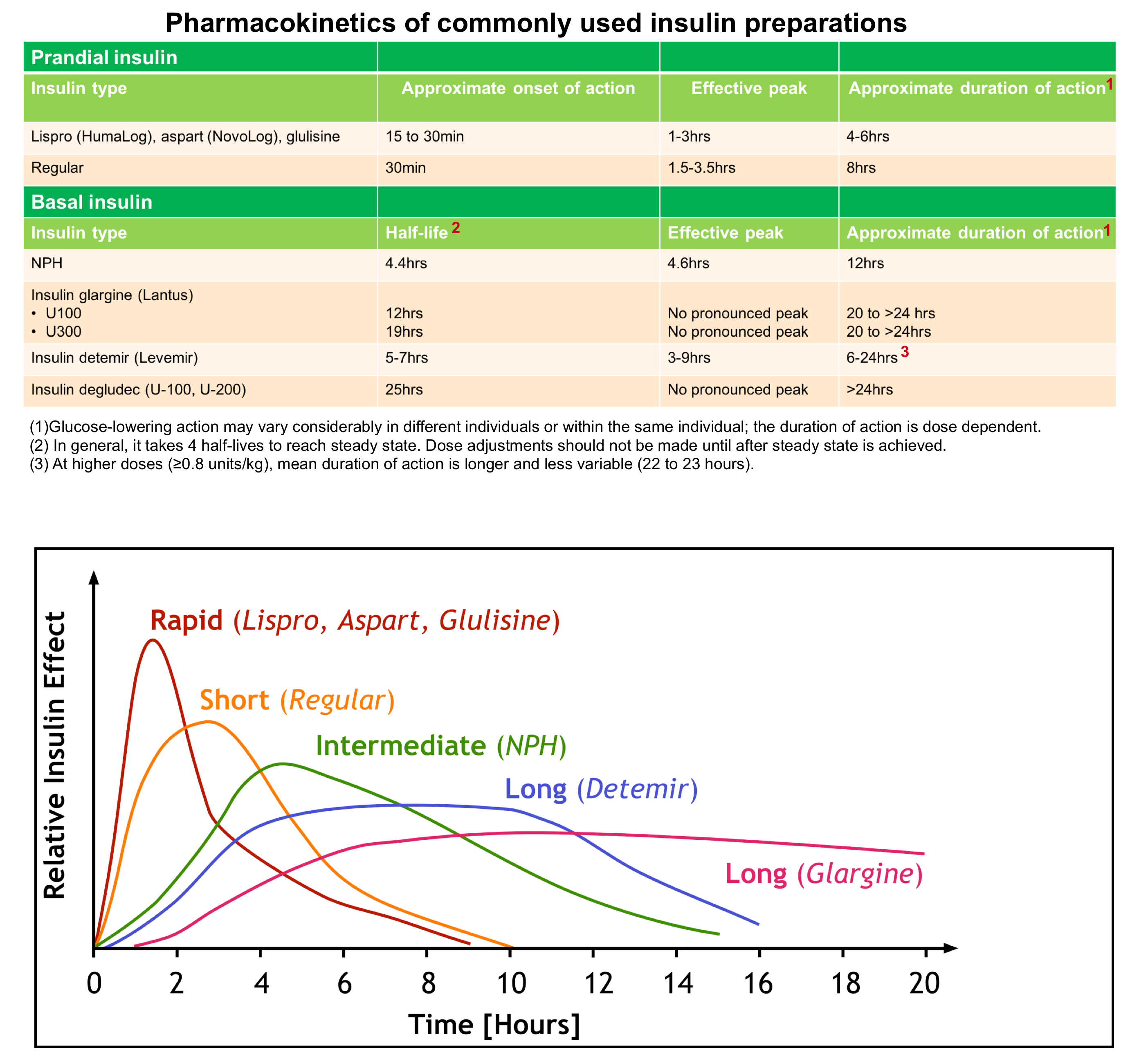

- In hypoglycemic patients on longer acting insulin, the situation is different as:

- Glargine (Lantus): It has an onset of action of 1-2 hours. However, there is no peak of insulin levels (see above). This is equivalent to the basal rate of insulin released by the pancreas. Once patients are stabilized and meet the discharge criteria mentioned above, they can be discharged home.

- Levemir: It has an onset of action of 1-2 hours, lasts 24 hours and has a peak action at about 6-8 hours. These patients should be observed for 6-8 hours to make sure they don’t drop again. Once they have crossed that threshold, if they are maintaining glucose levels, able to tolerate oral intake and follow-up with their primary care doctor, they can be discharged home.

- Otherwise, the patient should be admitted to a monitored bed.

- Patients requiring more frequent fingerstick glucose checks on dextrose infusions may require a higher level of care, such as in an intermediate medical care unit or intensive care unit (ICU), depending on local institutional policies regarding the frequency of fingerstick monitoring.

- If sulfonylurea poisoning is suspected or confirmed, the patient is at risk for recurrent hypoglycemia and should be admitted for monitoring and consideration of ongoing octreotide therapy.

👉After you treat hypoglycemia, follow the patient’s glucose carefully. Hypoglycemia frequently recurs. For example, insulin or sulfonylurea overdoses will out-last the glucose you give to the patient.

Prevention of hypoglycemia in critically ill patients

- Upon admission to the ICU discontinue any oral hypoglycemic medications. Hyperglycemia should be controlled with insulin therapy only.

- Be conservative with insulin dosing:

- Don’t try to achieve tight glycemic control. A glucose target of <220-250 mg/dL is fine for most patients.

- When in doubt, dose insulin conservatively. Hyperglycemia is less dangerous than hypoglycemia.

- Patients with cirrhosis or acute hepatic failure tend to develop hypoglycemia, so monitor their glucose levels and avoid giving them insulin. Some patients with severe hepatic failure will require a continuous dextrose infusion to avoid hypoglycemia.

Further going

References

1. Cryer PE, Axelrod L, Grossman AB, Heller SR, Montori VM, Seaquist ER, Service FJ; Endocrine Society. Evaluation and management of adult hypoglycemic disorders: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009 Mar;94(3):709-28. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1410. Epub 2008 Dec 16. PMID: 19088155

2. Krinsley JS, Grover A. Severe hypoglycemia in critically ill patients: risk factors and outcomes. Crit Care Med. 2007 Oct;35(10):2262-7. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000282073.98414.4B. PMID: 17717490

3. Diabetes Canada Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee, Yale JF, Paty B, Senior PA. Hypoglycemia. Can J Diabetes. 2018 Apr;42 Suppl 1:S104-S108. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2017.10.010. PMID: 29650081

4.American Diabetes Association. 13. Diabetes Care in the Hospital. Diabetes Care. 2016 Jan;39 Suppl 1:S99-104. doi: 10.2337/dc16-S016. PMID: 26696689

5. Moore C, Woollard M. Dextrose 10% or 50% in the treatment of hypoglycaemia out of hospital? A randomised controlled trial. Emerg Med J. 2005 Jul;22(7):512-5. doi: 10.1136/emj.2004.020693. PMID: 15983093; PMCID: PMC1726850

6. Alsahli M, Gerich JE. Hypoglycemia. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2013 Dec;42(4):657-76. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2013.07.002. PMID: 24286945

Add comment