January 21, 2023 by Shahriar Lahouti.

CONTENTS

- Preface

- Antibiotic allergy label

- Basic

- Approach to beta-lactams allergy

- RECAP

- Going further

- Media

- Appendix

- References

Preface

The vast majority of patients labelled as penicillin or beta-lactam allergic are not deemed truly allergic when appropriately stratified for risk, tested, and re-challenged. This mislabeling carries important risks for individual and public health. In this post an approach to determining whether a patient with reported penicillin allergy can be treated with penicillins or related beta-lactam antibiotics is reviewed.

Antibiotic allergy labels

Approximately 10% of the population carry a label of penicillin or beta-lactam allergy. However most of these patients labeled with penicillin or cephalosporins allergy are not allergic (i.e. they tolerate penicillin and related drugs)*.

Reasons of mislabeling

- The original reaction might not have been an allergy (there could be intolerance, a viral exanthem, or a drug-infection interaction)*.

- The original reaction (even if it was an immunological reaction), might not recur with re-challenge.

- IgE-mediated reactions to beta-lactams can wane over time. Almost 80% of patients who are positive for a penicillin skin test are no longer sensitive when re-challenged after a period of 10 years *.

Clinical implications of unverified antibiotic allergy labels

Unnecessary withholding of penicillins or cephalosporins in patients who are labeled as allergic on the basis of history alone, carries important risks for individual and public health, as it is associated with increased use of second-line or broader-coverage antimicrobial treatments (e.g. quinolones, vancomycin, clindamycin). These treatments may increase the risk for antimicrobial resistance and adverse events, including * *

- Increased rate of clinical failure

- Beta-lactam antibiotics are often the most effective treatment. Some examples are:

- Nafcillin or cefazolin are more effective against methicillin-sensitive Staph aureus (MSSA) than vancomycin.

- Avoiding beta-lactam antibiotics leads to suboptimal treatment with less effective antibiotics (e.g. vancomycin or clindamycin) *.

- Benzathine penicillin is the treatment of choice for patients with syphilis and ceftriaxone is the treatment of choice for patients with gonorrhea *.

- Nafcillin or cefazolin are more effective against methicillin-sensitive Staph aureus (MSSA) than vancomycin.

- Beta-lactam antibiotics are often the most effective treatment. Some examples are:

- Increased antibiotic toxicity

- Development and spread of certain types of drug-resistant bacteria such as MRS, VRE *.

- One study assessed various risk factors for the development of vancomycin-resistant enterococcus (VRE) in a medical intensive care unit. Among the various classes of antibiotics used prior to transfer to the MICU, quinolones had the strongest association with subsequent development of VRE (odds ratio = 8.6), whereas treatment with penicillins/beta-lactamase inhibitors was not associated with developing VRE *.

- Higher rate of Clostridioides difficile infection (esp. most commonly associated with clindamycin and fluoroquinolones use)*.

- Development and spread of certain types of drug-resistant bacteria such as MRS, VRE *.

Other caveats

- Penicillin allergy is a misleading term!

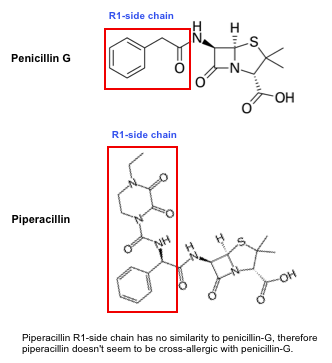

- Not all penicillins are cross-allergic. For example, piperacillin doesn’t seem to be cross-allergic with penicillin-G (👇below).

- Some penicillins are cross allergic with non-penicillins beta-lactam antibiotics. For example amoxicillin may have cross-reactivity with some first generation cephalosporins.

- New data are emerging on rate of cross-reactivity between beta-lactam antibiotics.

- For example, cross-reactivity between penicillin and cephalosporin drugs occurs in <2% of cases, while previously reported around 8% *.

Basics

Adverse drug reaction

An adverse drug reaction is a general term referring to any unexpected reaction to a medication. Adverse drug reactions may be broadly divided into 2 types:

- Type A reactions (~90%)

- Non-immunologic drug reactions that are predictable from the known pharmacologic properties of a drug. For example antibiotic induced diarrhea, aminoglycoside nephrotoxicity, hepatic failure associated with acetaminophen overdose.

- Type B (hypersensitivity) reactions (~10%)

- Unpredictable reactions to the drugs leading to signs and symptoms that are different from the pharmacologic actions of the drug. The most common form of hypersensitivity reactions is allergic drug reaction.

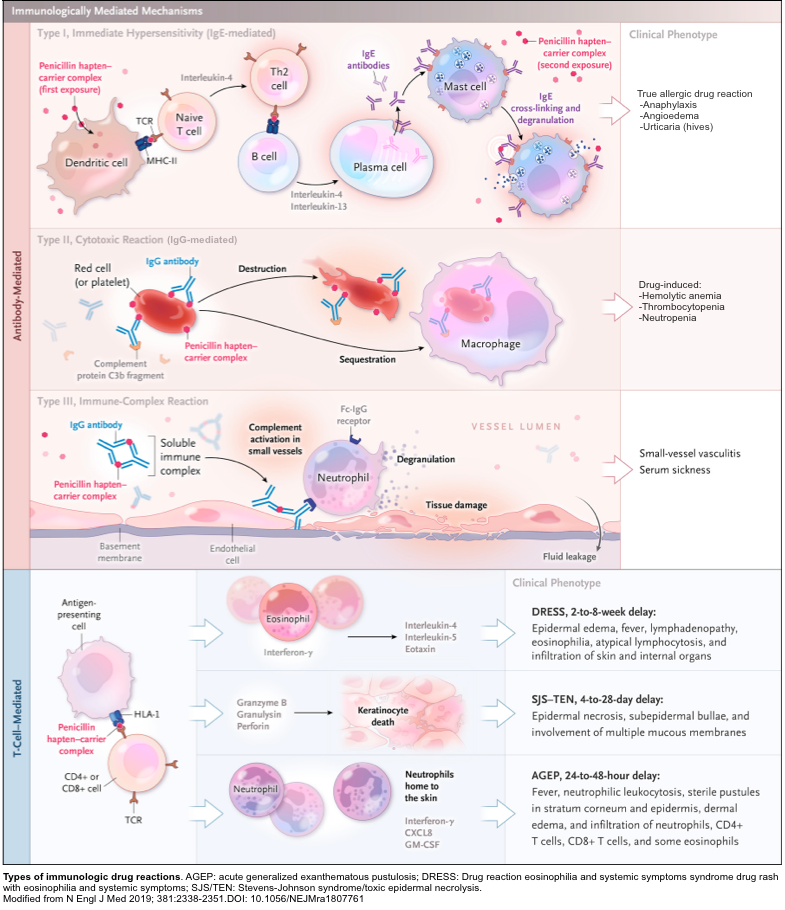

- Allergic drug reaction refers to a specific immune response elicited by the drugs and can be classified into 4 different categories (figure below) *.

- Allergic drug reaction refers to a specific immune response elicited by the drugs and can be classified into 4 different categories (figure below) *.

- Unpredictable reactions to the drugs leading to signs and symptoms that are different from the pharmacologic actions of the drug. The most common form of hypersensitivity reactions is allergic drug reaction.

Classifications of allergic drug reactions

Type-I hypersensitivity, IgE-mediated (true allergic reaction)

- Mechanism

- Mast-cell degranulation via IgE antibodies against the drug

- Clinical symptoms

- Onset: <1 h typical, but can be considered within 6 h of exposure *.

- Mild form: Urticaria

- More severe: Angioedema, anaphylaxis

- Antibiotic examples

- Penicillins, cephalosporins

- Diagnosis

- History, physical exam, skin testing, and drug challenge.

- Treatment

- Mild: Antihistamines

- Severe: epinephrine, steroid, antihistamines.

- Antibiotic recommendations

- Avoid drug and cross-allergic drugs in the future.

- If use of the drug is essential, desensitization may be performed.

- Differential diagnosis:

- Viral exanthem, or a drug-infection interaction (e.g. EBV infection)*

- Anaphylactoid reaction (pseudoallergic drug reaction)

- Mechanism:

- The offending drug directly stimulates the mast cells, causing release of mediators.

- Clinical symptoms:

- Occurs immediately after administration of drug with clinical picture almost similar to true allergic reaction (though they have less tendency to cause severe reactions and shock).

- Antibiotic examples:

- Vancomycin (red man syndrome), fluoroquinolones (urticaria most reactions)

- Diagnosis: Clinical diagnosis based on scenario.

- Treatment:

- Antihistamine (epinephrine, steroid for more severe cases)

- Antibiotic recommendations:

- Presence of this reaction is not a contraindication to using the drug in future. However, the drug should be administered more slowly or premedicated with antihistamines or corticosteroids.

- Mechanism:

- Viral exanthem, or a drug-infection interaction (e.g. EBV infection)*

Type-II hypersensitivity, IgG-mediated (cytopenias)

- Mechanism

- IgG and complement-mediated phagocytosis or cytotoxicity

- Clinical symptoms

- Onset: Often <72 h, but can be up to 15 days *.

- Hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, or vasculitis

- Antibiotic examples

- Penicillins, cephalosporins, sulfonamides, dapsone, rifampicin

- Diagnosis

- History, physical exam, targeted laboratory evaluation, and biopsy as indicated

- Treatment

- Steroid and/or intravenous immunoglobulin, or other immunosuppressants or immunomodulators

- Antibiotic recommendations

- Avoid drug in the future, or agents from same class.

Type-III hypersensitivity (serum sickness-like reaction)

- Mechanism

- Creation of antibody-antigen complexes

- Clinical symptoms

- Onset: Delayed (typically days to 1-3 weeks) after administration of the drug.

- Fever,rash, arthralgia, vomiting, and diarrhea (uncommon in adults).

- Skin lesions are characterized by fxed erythematous and edematous patches/plaques and annular lesions with central clearing and/or purplish discoloration *.

- Unlike true serum sickness, renal and hepatic involvement is rare *.

- Antibiotic examples

- Penicillin, amoxicillin, cefaclor, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole

- Diagnosis

- History, physical exam, skin biopsy as indicated. Certain laboratory evaluation including differential blood count, ESR, CRP, total complement, C3, C4, urinalysis to assess for proteinuria.

- Treatment

- Steroid in severe cases

- Antibiotic recommendations

- Generally a benign event and future courses of medication are unlikely to lead to recurrence.

Type-IV hypersensitivity (T-cell mediated)

Isolated cutaneous disease

- Maculopapular rash (a.k.a. benign T-cell-mediated drug reaction)

- Mechanism

- Type IV cell-mediated reaction involving eosinophils

- Clinical symptoms

- Onset: Appears after days to weeks of therapy (typically ~2 weeks)*.

- Morbilliform rash, often with peripheral blood eosinophilia

- Antibiotic examples

- Amoxicillin, sulfonamide antibiotics

- Diagnosis

- History, physical exam.

- Treatment

- Antihistamines or topical steroid (systemic steroid in severe cases).

- Antibiotic recommendations

- Generally benign, can re-challenge with same drug depending on scenario. In some cases, may even treat through this reaction, with careful monitoring for development of a more severe reaction.

- Mechanism

Primary single organ disease

- Acute interstitial nephritis (AIN)

- Mechanism

- CD4 or monocyte immune injury to the renal tubulointerstitium

- Clinical symptoms

- Onset: 3 days to 4 weeks

- Acute kidney injury, sometimes with skin rash *.

- Antibiotic examples

- Semi-synthetic anti-staphylococcal penicillins (e.g. nafcillin, oxacillin), fluoroquinolones, rifampicin *.

- Diagnosis

- Active urinary sediment (e.g. with leukocyte casts), peripheral blood eosinophilia may be seen. Renal biopsy is diagnostic

- Treatment

- Steroid, possibly additional immunosuppressives

- Antibiotic recommendations

- Avoid drug in the future, or agents from same class.

- Mechanism

- Drug-induced liver injury

- Mechanism

- CD8 T-cells stimulate keratinocyte death (Type IV hypersensitivity)

- Clinical symptoms

- Onset: From 5 days to 12 weeks (typically more than 4 weeks)

- Hepatitis (often with substantially elevated bilirubin), may have rash, fever, or eosinophilia *.

- Antibiotic examples

- Amoxicillin-clavulanate, flucoxacillin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, nitrofurantoin, minocycline, rifampicin *.

- Diagnosis

- Laboratory evaluation for hepatitis (often diagnosis of exclusion). Liver biopsy in severe cases.

- Treatment

- Steroid

- Antibiotic recommendations

- Avoid drug in the future, or agents from same class.

- Mechanism

Systemic or multisystemic disease

- Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS) & Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN)

- Mechanism

- CD8 T-cells stimulate keratinocyte death (Type IV hypersensitivity)

- Clinical symptoms

- Onset: 4 days to 4 weeks (for many antimicrobials shorter latency is typical) *.

- Rash with desquamation, mucosal lesions (mouth, eyes, genitals) with mucositis, or fever.

- SJS: <10% BSA (a limited form of disease)

- SJS–TEN overlap: 10–30% BSA

- TEN: >30% BSA (most severe form of disease with greater area of involvement)*.

- Antibiotic examples

- Sulphonamide antimicrobials,antimycobacterials, macrolides, or quinolones.

- Diagnosis

- History (blistering rash with skin sloughing), physical exam (Nikolsky and Asboe-Hansen signs),skin biopsy.

- Treatment

- Immediate removal of drug; aggressive supportive care in ICU or burn unit setting; pulse corticosteroids, etanercept, or cyclosporine

- Antibiotic recommendations

- Absolutely avoid drug in the future, or agents from same class.

- Mechanism

- Drug reaction eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome (DRESS)

- Mechanism

- T-cell stimulated eosinophils and lymphocytic infiltration of skin & internal organs

- Clinical symptoms

- Onset: 2-6 weeks

- Fever, rash, peripheral blood eosinophilia, lymphadenopathy, or organ involvement (often liver or kidney).

- Antibiotic examples

- Vancomycin, all beta-lactam antibiotics, sulphonamide antibiotics *.

- Diagnosis

- History, physical exam, skin biopsy as indicated. Certain laboratory evaluation including differential blood count, ESR, CRP, total complement, C3, C4, urinalysis to assess for proteinuria.

- Treatment

- Steroid in severe cases

- Antibiotic recommendations

- Avoid drug in the future, or agents from same class

- Mechanism

- Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis (AGEP)

- Mechanism

- T-cell stimulated neutrophilic inflammation

- Clinical symptoms

- Onset: <48 h (typically within 24 h)

- Acute pustular eruption characterized by widespread non-follicular sterile pustules, fever, facial edema, or neutrophilia; 25% of patients have oral involvement. In severe cases can cause systemic inflammation with shock *.

- Antibiotic examples

- Aminopenicillins, other beta-lactams, clindamycin, vancomycin, fluoroquinolones, sulfonamides.

- Diagnosis

- History, physical exam, fever, lab evaluation showing neutrophilic leukocytosis with mild eosinophilia, skin biopsy.

- After recovery, patch testing can help determine the causative agent.

- Treatment

- Steroid in severe cases

- Antibiotic recommendations

- Avoid drug in the future, or agents from same class.

- Mechanism

Beta-lactam antibiotics

Classification

- Beta-lactams (BL) are the first-choice antibiotics to treat the majority of bacterial infections. Beta-Lactam antibiotics include:

- Penicillins:

- Natural penicillins: Penicillin V (oral), penicillin G (IV), benzathine penicillin (IM), and procaine penicillin (IM).

- Antistaphylococcal penicillin: Dicloxacillin, naficillin, oxacillin, cloxacillin.

- Aminopenicillins: Amoxicillin, amoxicillin- clavulanate, ampicillin.

- Extended-spectrum penicillins: Piperacillin, ticarcillin.

- Cephalosporins

- Carbapenems: Imipenem, meropenem, ertapenem

- Monobactams: Aztreonem

- Penicillins:

Structure

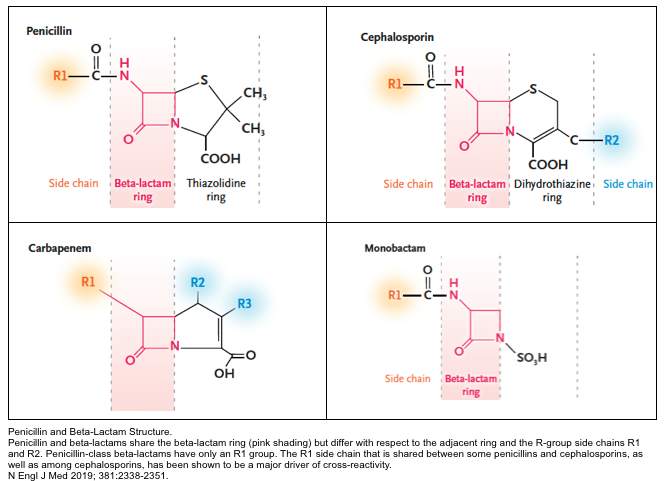

- β-Lactam antibiotics share a core beta-lactam ring but differ with respect to the adjacent ring and the R-group side chains R1 and R2 (shown below).

Beta-lactam allergy and cross‐reactivity

All beta-lactam antibiotics share a core beta-lactam ring, therefore if we presume that patients are allergic to the core ring, then a patient with allergy to one beta-lactam, should be allergic to all drugs in this class. However this is not true!

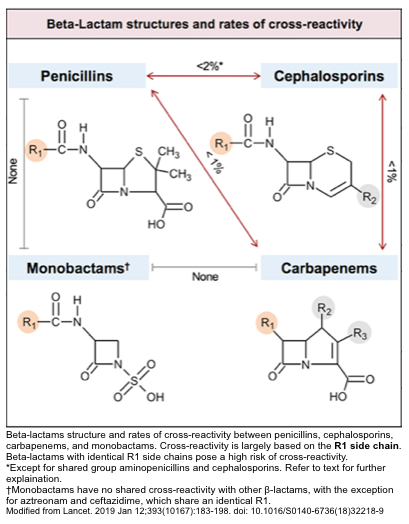

- In fact, among patients with IgE-mediated allergy to penicillins, less than 2% may show an allergic reaction to cephalosporins *.

- The rate of cross-reactivity between cephalosporins and carbapenems is lower than 1%.

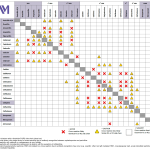

- The rates of cross-reactivity between penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems, and monobactams are shown below👇 *.

Mechanism of IgE-mediated allergy

- As explained above, the core beta-lactam ring does not seem to be the major driver of allergy.

- Rather, the R1 side chain of each individual beta-lactam antibiotic is thought to contribute to development of allergy *.

Beta-lactams cross-reactivity

Structural similarity between R1-side chain is the key factor in determining cross-reactivity.

- Cross-allergy is a matter of similarity between R1-side chains (not necessarily how a specific antibiotic is classified).

- For example, aztreonam and ceftazidime have identical R1 side-chains and are cross-allergic (despite belonging to different classes of beta-lactams).

- On the other hand, patients with allergy to penicillin-G do not have a cross-allergic reaction with piperacillin (despite that both drugs are classified as penicillin). As shown below, there is no R1-side chain similarity between these two drugs.

The structure of most beta-lactams are shown in appendix. Similarity between R1-side chain provide a background for understanding the cross-reactivity of various beta-lactams *.

Cross-allergic beta-lactams

Based on side chain similarities, eight groups of cross-allergic beta-lactam antibiotics can be identified as listed below. This framework can be clinically helpful in choosing an appropriate antibiotic which is not cross-allergic with medications that the patient is allergic to it *.

| Group 1. Cross allergic antibiotic: Aminopenicillins and selected cephalosporins G1, G2 -Ampicillin, amoxicillin -Some G1 cephalosporins, e.g. cefadroxil, cephalexin. -Some G2 cephalosporins, e.g. cefaclor, cefprozil. -Penicillin G, penicillin V 👉Tip: When a patient is labeled with “penicillin allergy”, it most commonly denotes to aminopenicillin allergy (listed above). |

| Group 2. Cross allergic antibiotic: Antistaphylococcal penicillin – Naficillin – Oxacillin?, flucloxacillin? 👉Structurally, the R1 side-chain of nafcillin is rather unique, and unlike other beta-lactams. Nafcillin does not appear to be cross-allergic with penicillin G or aminopenicillins. 👉Cross-reactivity of nafcillin with other antisataphylococcal penicillins remains unclear. |

| Group 3. Cross allergic antibiotic: Extended spectrum penicillins – Piperacillin-Tazobactam – Sulbactam, clauvlunate 👉The structure of piperacillin-tazobactam is quite distinct from aminopenicillins or cephalosporins. This predicts a lack of cross-allergy. 🚩It is unclear whether tazobactam could be cross-allergic with sulbactam or clavulanate. Caution should be exercised for patients with a history of severe allergy to ampicillin-sulbactam or amoxicillin-clavulanate *. |

| Group 4. Cross allergic antibiotic: Cefazoline 👉The unique R-side chain of cefazolin make it non-cross allergic with other beta lactams *. |

| Group 5. Cross allergic antibiotic: G3 cephalosporins and cefepime – Most G3 cephalosporins (except ceftazidime): Ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, cefpodoxime – G4: Cefepime |

| Group 6. Cross allergic antibiotic -Ceftazidime (G3) -Cefiderocol (a G5 cephalosporin) -Aztreonam 👉Ceftazidime and aztreonam have the same R1 side chain. This makes them cross-allergic, even though they are in different sub-classes of beta-lactam antibiotics. 👉Aztreonam has historically been regarded as safe in “beta-lactam allergy,” but it is actually cross-reactive with ceftazidime. 👉Ceftazidime might be an option for some patients unable to tolerate cefepime or other G3 cephalosporins |

| Group 7. Cross allergic antibiotic – Ceftaroline (G5) 👉No reports of anaphylaxis to ceftaroline has been reported so far. However, a recent retrospective case series suggested that ceftaroline may cause unusually high rates of T-cell mediated hypersensitivity reactions (e.g. cytopenias, hepatitis, nephritis, desquamating skin rash). |

| Group 8. Cross allergic antibiotic. Carbapenems – Ertapenem – Meropenem 👉Meropenem has a very small R1 side chain, explaining why allergy to meropenem does not exist. 👉Meropenem is safe to use in patients with a history of anaphylaxis to aminopenicillins. 🚩Imipenem-cilastatin may cross-react with some beta-lactam antibiotics, most likely due to the cilastatin component. |

Approach to beta-lactams allergy

History

A thoughtful allergy history is an essential step to determining a “pretest probability” regarding whether the patient has a clinically significant allergy. Questions to clarify beta-lactam adverse reaction history *:

- Which medication was prescribed, and what was the route of administration?

- What exactly were the symptoms?(1) Specifically ask about:

- Raised, erythematous, pruritic rash with each lesion typically lasting <24 hours? (urticaria)

- Swelling of the tongue, mouth, lips, or eyes?

- Lesions or ulcers involving the mouth, lips, or eyes; skin desquamation.

- Rashes that were not hives, were mild, or delayed in onset. (mild type IV reaction).

- Respiratory or hemodynamic changes?

- Organ involvement such as hematologic, renal, or hepatic.

- Joint pain (serum-sickness like reaction).

- How was the reaction treated?

- Was epinephrine administered to suggest anaphylaxis? Was there a need for urgent care or hospitalization?

- Timing:

- What was the timing of the reaction after taking penicillin, e.g. minutes, hours, or days later?

- An IgE-mediated allergic reaction should occur within minutes or a few hours.

- How long ago did the reaction happen?

- This question is most important for immediate reactions, because 80% of patients may lose the sensitivity with time if they have no further penicillin exposures. In contrast, the natural history of serious delayed reactions is not as well-known.

- What was the timing of the reaction after taking penicillin, e.g. minutes, hours, or days later?

- Ask the patient (and/or interrogate the chart) to determine which antibiotic(s) the patient has been able to tolerate.

- If the patient has recently tolerated an antibiotic, this is powerful evidence that the same antibiotic (or a related agent) would be tolerated again.

- Often patients are able to tolerate penicillins, but the “penicillin allergy” remains on the electronic medical record.

(1)Although there are many types of rashes that result from infectious, environmental, and/or autoimmune triggers, familiarity with the following 3 general categories of rashes in drug allergy practice is useful for nonspecialists (figure below)*:

- IgE-mediated cutaneous reactions (e.g. urticaria)

- Benign T-lymphocyte–mediated cutaneous reactions

- Severe cutaneous adverse reaction “SCAR”.

Risk stratification

Risk stratification enable provider to decide if alternative beta-lactam antibiotic can be administered and also whether penicillin skin testing or drug challenges are appropriate.

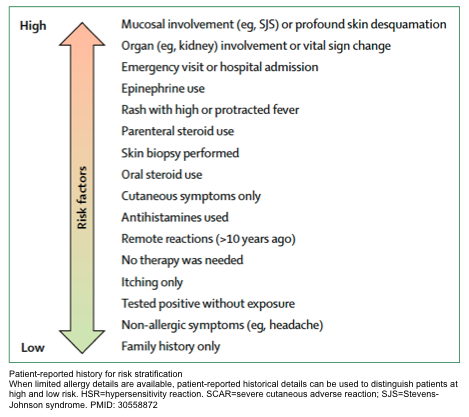

- Based on the reported history (figure below), patients can be stratified into low, moderate and high risk, after the allergy history is determined to be inconsistent with SCAR, hemolytic anemia, an organ-specific reaction (e.g. acute interstitial nephritis, DILI) or serum sickness *.

Low risk

- “Isolated” reactions that are unlikely allergic (e.g. gastrointestinal symptoms, headaches)

- Pruritus without rash

- Remote (>10 y) unknown reactions without features of IgE

- Family history of penicillin allergy

👉Note that even in the context of a low-risk allergy history, patients with unstable or compromised hemodynamic or respiratory status and pregnant patients should be considered as having at least a moderate-risk history because of host factors that may result in poor outcomes *.

Medium risk

- Urticaria or other pruritic rashes (either immediate or delayed).

- Reactions with features of IgE but not anaphylaxis

- IgE features classically include cutaneous symptoms, such as itching, flushing, urticaria, and angioedema, but also involve respiratory system (rhinitis, wheezing, shortness of breath, bronchospasm), cardiovascular system (arrhythmia, syncope, chest tightness), and GI system (abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea) symptoms *.

High risk

- Anaphylactic symptoms

- Positive skin testing

- Recurrent reactions

- Reactions to multiple β-lactam antibiotics

Consideration

- Patients with a history of drug allergies are at a higher risk for reactions than patients without them.

- The baseline risk for any reaction to β-lactam antibiotics is approximately 2.0%.

- It’s important to realize that the risk of an anaphylactic reaction is never zero, for any patient or with any medication. By enlarge, patients with a history of anaphylaxis to one medication may be more likely to develop anaphylaxis to other medications.

- Patients with a history of penicillin allergy may react to a placebo during drug challenges; a nocebo effect has been documented in up to 10% of drug-challenged patients.

- The baseline risk for any reaction to β-lactam antibiotics is approximately 2.0%.

- Individuals with underlying chronic urticaria do not have an increased risk for immunologically mediated penicillin hypersensitivity *.

Technique for management of allergy

Graded challenge

- Graded challenge involves administering a medication to a patient in a graduated manner under close observation. It is based on the principle that a certain amount of the medication is needed to elicit symptoms.

- Graded challenge does not modify the allergic response to the drug or prevent recurrent reactions. The patient is first exposed to a small dose of the drug and, if this is tolerated, it proves that patient is not allergic to to the drug given at the dose used. Therefore escalating doses are administered.

- Unlike penicillin skin testing, this can be performed with any intravenous antibiotic.

- Indications:

- It is used to exclude allergy to the medication in question, and is most appropriate for a patient who is unlikely to be allergic to that drug (i.e. anaphylactic reaction is possible, but seems less likely).

- ⚠️Contraindications

- Patient with a positive response in a prior drug allergy test (skin or in vitro).

- Patients with the following types of reactions:

- Blistering dermatitis (e.g. Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis).

- Sloughing of the skin.

- Severe generalized hypersensitivity reactions involving internal organs (drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms).

- Milder dermatoses with mucous membrane lesions (e.g. erythema multiforme).

- Challenge protocols

- There are several different protocoles for drug challeneg test in subjects with immidiate reactions. One common approach is as follows: infuse 10% of the dose slowly over ~60 minutes, with close observation. If this is tolerated, the remainder of the dose is given at the usual rate *.

- This is easy to do with any antibiotic infused via a mini-bag (as most antibiotics are, in critical illness). You’re essentially starting the antibiotic at a very low infusion rate and carefully watching the patient. If nothing happens after an hour, then increase the infusion to a normal rate.

- The only drawback is that this will delay administration of antibiotic by about an hour.

- Other considerations

- Patients should not be premedicated with antihistamines or glucocorticoids, because these agents may mask early signs of an allergic reaction *.

- If patient is taking a beta-blockers for control of hypertension, it should be withheld for 24h before challenge, as these agents can interfere with treatment of anaphylaxis with epinephrine, should that be necessary. In contrast, beta-blockers that are taken to control arrhythmias should not be withheld without consulting a cardiologist *.

- There are several different protocoles for drug challeneg test in subjects with immidiate reactions. One common approach is as follows: infuse 10% of the dose slowly over ~60 minutes, with close observation. If this is tolerated, the remainder of the dose is given at the usual rate *.

Desensitization

- Desensitization involves the administration of escalating doses of a drug to a patient with a known allergy (or highly suspected allergy).

- Desensitization alters a patient’s adverse immune response to a drug and results in temporary tolerance, allowing the patient with a hypersensitivity reaction to receive an uninterrupted course of the medication safely.

- Once the medication is discontinued, the patient’s hypersensitivity to the medication returns.

- Desensitization is used occasionally in situations where a specific antibiotic is uniquely required.

- With growing our understanding about the lack of cross-reactivity between most antibiotics, this is rarely required currently.

- Desensitization protocols

- A validated protocols must be followed carefully.

- Initially a very tiny antibiotic dose is administered, and this is gradually increased over time (e.g. over a period of 6-12 hours).

- If allergic reactions occur, antibiotic administration is temporary held and the reaction is treated. Once the reaction subsides, additional antibiotic is administered.

- Must be performed only in an ICU or ED with the capacity to immediately treat anaphylaxis or angioedema.

👉Pearl

- Graded challenge: Test for allergic reaction and stop drug administration if a reaction occurs.

- Desensitization: Intentionally provoke an allergic reaction and treat through it. This involves giving very small doses of a drug and gradually increasing in a stepwise manner until a full therapeutic dose is reached.

Skin testing

- Skin testing is sensitive for an allergy (a negative test carries ~98% predictive value that penicillin can be tolerated).

- Specificity of a positive result is murky (since those patients with a positive test are not challenged with penicillin!).

- 50% of patients with a positive result may actually be able to tolerate penicillin.

- Skin tests have been clinically validated only for penicillin allergy (not for other antibiotics).

- A negative penicillin allergy doesn’t exclude allergies to structurally unrelated beta-lactams (e.g. cephalosporins).

- It is time consuming and requires experienced staff. These are logistical barriers to use in critically ill patients with acute infection.

- It has been realized that natural penicillins are actually cross-allergic with very few antibiotics (figure above).

- 👉Having said that, skin testing is not clinically hellpful these days esp. for critically ill patients with acute infection.

Selecting an alternative antibiotic

For most critically ill patients presenting to ED with an acute infection, logistics don’t allow for sophisticated approaches such as skin testing or desensitization. Selection of a safe and effective antibiotic can be simply made on risk stratification and understanding which antibiotics are truly cross-allergic with each other.

Approach to choosing an appropriate antibiotic

- Risk stratification (above)

- Take a thorough history (above)

- Keep in mind that attempting to achieve a zero risk is virtually impossible and may lead to more harms (e.g. placing the patient on a regimen of second-line or broader-coverage antimicrobial treatments which likely increases their overall risk of being harmed by a medication side-effect). More on this above.

- Review in EMR for the antibiotic that patient mostly tolerate.

- Select an antibiotic that is not cross allergic, or may employ graded challenge or desensitization technique if possible (following algorithm).

- How to select an antibiotic that is not cross allergic?

- Choose an antibiotic that is not cross-allergic with the medication that patient is allergic to, based on R1-side chain similarity(see above), or

- Use cross-reactivity chart (see appendix 2).

- How to select an antibiotic that is not cross allergic?

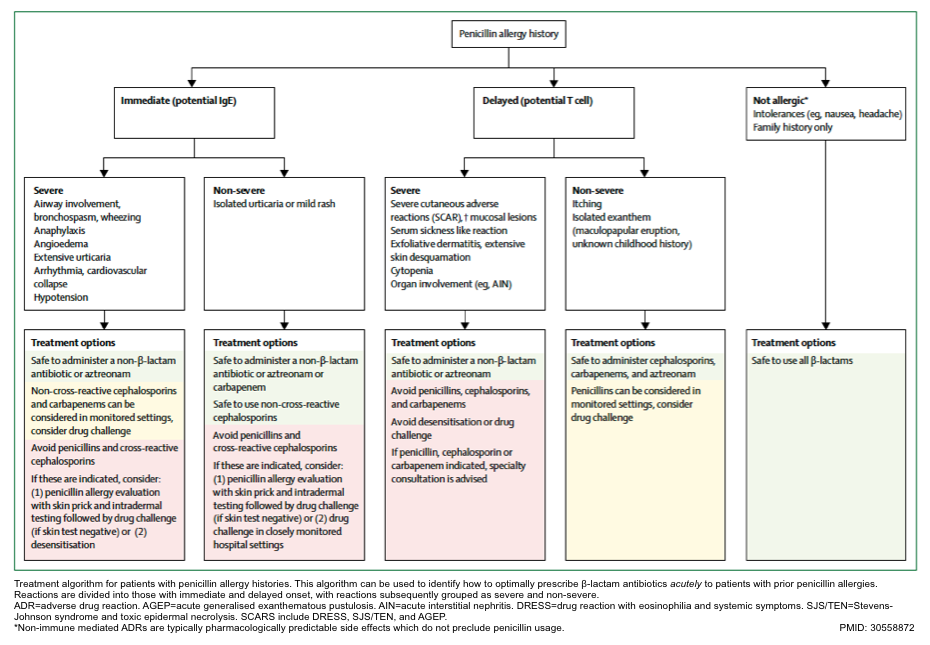

Treatment algorithm for patients with penicillin allergy history

Patients with delayed reaction with organ dysfunction, OR severe cutaneous adverse reactions:

- Avoid beta-lactams (penicillins, cephalosporins, and carbapenems).

- It is safe to administer non-beta-lactam antibiotics or may consider aztreonam (if patient was not allergic to ceftazidime or cefiderocol).

- Avoid drug challenge or desensitization.

High risk patients

- Avoid cross-allergic beta-lactams.

- It is safe to administer non-beta-lactam antibiotics or may consider aztreonam (if patient was not allergic to ceftazidime or cefiderocol), Or may consider to give non-cross-reactive beta-lactams.

- Avoid drug challenge if risk of anaphylaxis is high.

Moderate risk patients

- Avoid cross-allergic beta-lactams.

- It is safe to administer non-beta-lactam antibiotics or may consider aztreonam (if patient was not allergic to ceftazidime or cefiderocol), Or may consider to give non-cross-allergic beta-lactams.

- May consider drug challenge in controlled setting.

Low risk patients

- Safe to use all beta-lactams.

RECAP

- Most patients labeled as penicillin or cephalosporin allergic, can tolerate the related drugs.

- Clinically significant IgE-mediated or T lymphocyte–mediated hypersensitivity is uncommon (<5%) to penicillins or cephalosporins.

- Penicillins and cephalosporins can cause a similar spectrum of allergic reactions at a similar rate.

- Cross-reactive allergy between penicillins and cephalosporins is rare, as is cross-reaction within the cephalosporin group (figure above).

- Patients should therefore not be labeled ‘cephalosporin-allergic’.

- Cross-reactive allergy may occur between cephalosporins (and penicillins) which share similar side chains.

- Generally, a history of a penicillin allergy should not rule out the use of cephalosporins, and a history of a specific cephalosporin allergy should not rule out the use of other cephalosporins with non-cross-reactive side chains.

- When recording a drug allergy in the patient’s records, it is important to identify the specific drug suspected (or confirmed), along with the date and nature of the adverse reaction.

- Records need to be updated after a negative drug challenge.

- In patients with a myriad of antibiotic resistance who require broad spectrum coverage, meropenem can be a safe option.

Going further

- Cephalosporins and penicillins cross-reactivity (Rebl EM)

- Ranking antibiotics in order of allergenicity (PulmCrit)

- Anaphylaxis to penicillins isn’t a contraindication to meropenem (PulmCrit).

- Is piperacillin-tazobactam safe in patients with penicillin allergy? (PulmCirt)

Media

Appendix

1.Chemical structure of beta-lactam antibiotics.

2.Cross-reactivity side-chain chart

References

Serum sickenss: Blanca R, Del Pozzo-Magana AL. Serum-sickness-like reaction in children:

review of the literature. EMJ Dermatol. 2019;7(1):106–11.

Add comment