13 October, 2022 by Shahriar Lahouti.

CONTENTS

- Preface

- Anatomy

- Etiology

- Gallstones

- Acalculous cholecystitis

- Other causes

- Clinical presentation

- Differential diagnosis

- Investigation

- Diagnostic criteria

- Complications

- Severity assessment of cholecystitis and cholangitis

- Treatment

- Going further

- Media

- Appendix

- References

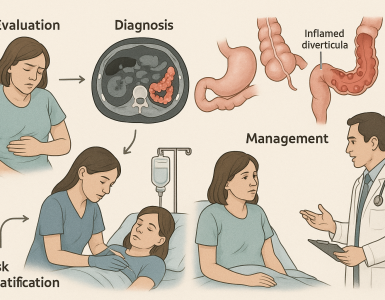

Preface

Biliary tract infection is a common cause of bacteremia and sepsis which is associated with high morbidity and mortality. This predominantly occurs as a complication of gallstone. In this post cholecystitis and cholangitis are reviewed in light of recent guidelines.

Anatomy

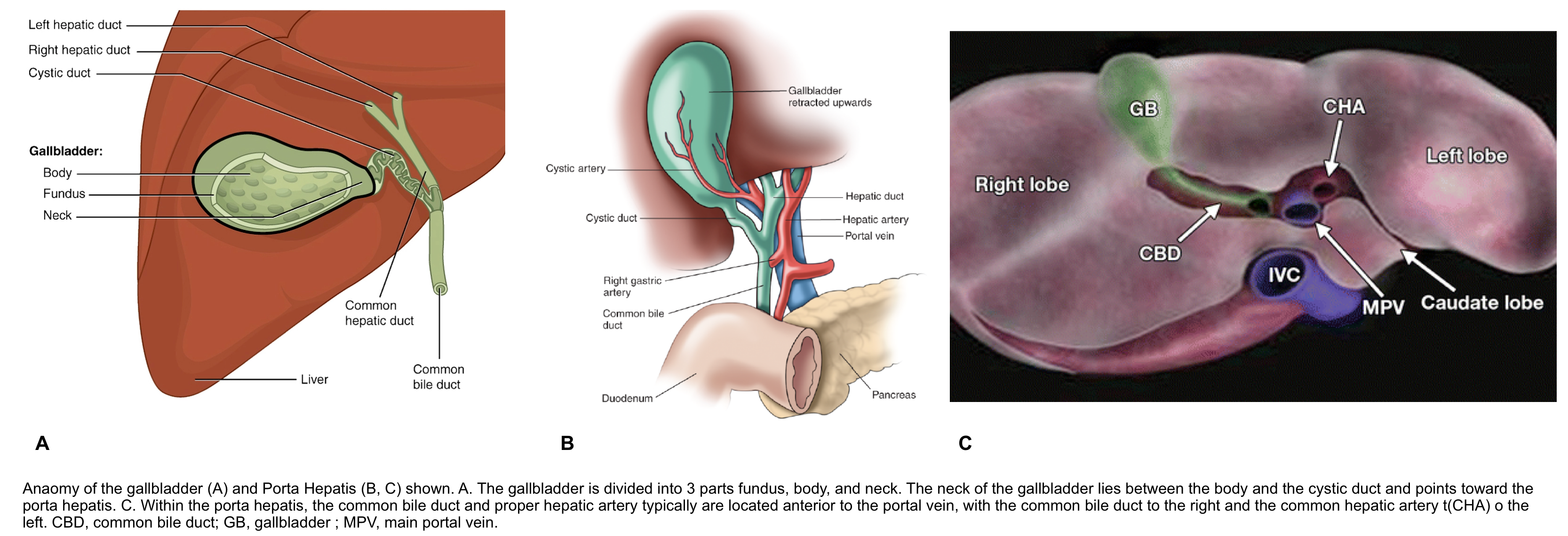

Bile is produced continuously by liver, stored and concentrated by gallbladder (GB), and released intermittently by GB contraction in response to presence of fat in duodenum.

- Hepatocytes form bile → bile canaliculi → interlobular biliary ducts → collecting bile ducts → right and left hepatic ducts → common hepatic duct → common bile duct → intestines.

Common bile duct forms in free edge of lesser omentum by union of cystic duct and common hepatic duct. It descends posterior and medial to duodenum, lying on dorsal surface of pancreatic head and joins with pancreatic duct to form hepaticopancreatic ampulla of Vater.

Gallbladder is 7-10 cm long, holds up to 50 mL of bile.

- Fundus is covered with peritoneum and relatively mobile; body and neck attached to liver and covered by hepatic capsule. Cystic duct: 3-4 cm long, connects GB to common hepatic duct.

Intrahepatic ducts

- Normal diameter of 1st and higher-order branches < 2 mm or < 40% of diameter of adjacent portal vein.

- 1st (i.e. Left hepatic and right hepatic ducts) and 2nd-order branches are normally visualized.

- Visualization of 3rd and higher-order branches is often abnormal and indicates dilatation.

Etiology

Gallstones

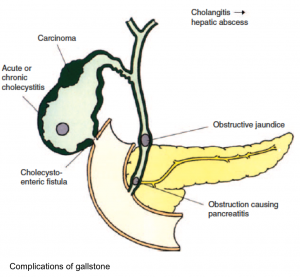

Patients with gallstone disease may be asymptomatic or may present with biliary pain or complications of gallstone disease, including:

- Acute cholecystitis: is the most common complication of gallstones.

- Choledocholithiasis with or without acute cholangitis

- Gallstone pancreatitis

- Other rare complications include gallstone ileus, Mirizzi syndrome, and gallbladder cancer.

Biliary sludge

- Biliary sludge can cause biliary colic and the same complications as stones via the same mechanisms.

- Symptomatic gallbladder sludge should be managed in the same manner as stones.

- Microlithiasis (biliary sludge) may also progress to macroscopic gallstones.

Acalculous cholecystitis

- It is defined as cholecystitis that occurs without a gallstone. This accounts for only 5%-10% of acute cholecystitis cases.

- It carries a mortality of 30%-90% in critically ill patients.

- Risk factors for acalculous cholecystitis include critical illness, major trauma, postoperative status, multiorgan failure, diabetes, immunosuppression, and severe burns, among others.

Other etiologies of biliary stasis

- Malignancy e.g. gallbladder cancer, cholangiocarcinoma, pancreatic cancer.

-

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

Clinical presentation

Uncomplicated symptomatic gallbladder stone

- Patients with biliary pain due to uncomplicated gallstone disease are usually not ill-appearing and do not have fever or tachycardia.

- Pain

- The classic description of biliary pain is an intense, dull postprandial discomfort in the right upper quadrant, epigastrium.

- The pain typically lasts at least 30 minutes, plateauing within an hour. The pain then starts to subside, with an entire attack usually lasting less than 6 hours.

- The pain is often associated with diaphoresis, nausea, and vomiting.

- The abdominal examination is generally benign.

- Biliary colic is visceral pain, and there are no peritoneal signs because the gallbladder is not inflamed.

- Laboratory test results (complete blood count, aminotransferases, bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, amylase, and lipase) are normal.

Uncomplicated symptomatic choledocholithiasis

- Patients are typically afebrile and present with biliary-type pain and laboratory testing that reveals a cholestatic pattern of liver test abnormalities (i.e. elevated bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase). They have a normal complete blood count and pancreatic enzyme levels.

Acute calculus cholecystitis

- Pain in right upper quadrant or epigastrium.

- Characteristically, acute cholecystitis pain is steady and severe and is typically prolonged (greater than 6 hours).

- Fever

- Nausea, vomiting, and anorexia

- Localizing signs

- Cholecystitis is associated with true local parietal peritoneal inflammation that is aggravated by movement.

- Abdominal examination usually demonstrates voluntary and involuntary guarding. Patients frequently will have a positive Murphy’s sign.

Acute cholangitis

- May share similar presentation of acute cholecystitis, including pain in right upper quadrant or epigastrium, fever, nausea, vomiting, and anorexia.

- Features more common in patients with cholangitis:

- Jaundice

- Shaking chills: Bacteremia is common, often leading to frank rigors. Occasionally, patients may present with sepsis and bacteremia in the absence of any localizing symptoms.

- Patients with acute cholangitis can also present with other complications including sepsis, multiple organ system dysfunction, portal vein thrombosis, gastrointestinal bleeding, and shock.

Differential diagnosis

- Acute pancreatitis

- Gallstones (including microlithiasis) are the most common cause of acute pancreatitis accounting for 40-70% of cases. However, only 3-7% of patients with gallstones develop pancreatitis.

- Small gallstones are associated with an increased risk of pancreatitis.

- Multiple small (< 5mm) stones are associated with a 4-fold higher risk of migration into the common bile duct and cause obstruction at the ampulla, compared with a single large stone.

- US: diffusely enlarged and hypoechoic pancreas with/without peripancreatic fluid.

- CT: focal or diffuse enlargement of the pancreas with heterogeneous enhancement with intravenous contrast.

- Necrosis of pancreatic tissue is recognized as lack of enhancement after intravenous contrast administration.

- A common bile duct stone may occasionally be visualized on contrast-enhanced abdominal CT scan. See here

- Liver abscess

- Combination diagnoses:

- Simultaneous cholecystitis plus cholangitis.

- Simultaneous cholangitis plus pancreatitis.

- Simultaneous cholangitis plus liver abscess.

- Fitz–Hugh Curtis syndrome

- Pylephlebitis (infective suppurative thrombosis of the portal vein)

- Procedural complication (e.g. bile duct leak due to laparoscopic cholecystectomy).

Investigations

Lab

- Complete blood count

- Leukocytosis with an increased number of band forms (i.e. a left shift).

- Inflammatory markers, e.g. CRP, procalcitonin.

- Both cholecystitis and cholangitis may cause elevation of inflammatory markers.

- Procalcitonin is proposed as a marker to determine risk for clinical deterioration and need for more emergent biliary decompression in cholangitis. In one study, it has been shown that procalcitonin levels at presentation were strongly associated with severity of disease and a level > 3.77 ng/mL was indicative of clinical deterioration.

- Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR).

- The performance of the NLR is superior to the white blood count in both cholecystitis and ascending cholangitis.

- Cholecystitis

- Cholangitis

- NLR >5.3 predicts cholangitis (68% sensitivity and 95% specificity) *

- This cutoff is higher than the cutoff for cholecystitis (~3), reflecting that cholangitis typically causes greater physiologic stress.

- Blood cultures (if suspected cholangitis).

- Up to 70% of patients with cholangitis will have positive blood cultures.

- Liver function tests (ALT, AST, alkaline phosphatase, and total bilirubin).

- Acute cholecystitis may cause mild elevations in serum aminotransferases, alkaline phosphatase along with hyperbilirubinemia and jaundice.

- Cholestatic pattern of liver test abnormalities is more suggestive for cholangitis

- Marked elevation of total bilirubin (e.g. >4 mg/dL, predominantly conjugated) and alkaline phosphatase (i.e. > 4 x UNL), are more consistent with cholangitis.

- Severe elevation of transaminases (occasionally >1.000 mg/dL) is occasionally seen in cholangitis due to acute biliary obstruction. This pattern may also reflect microabscess formation in the liver.

- Serum amylase and lipase

- Mild elevation of amylase and lipase may be seen with acute cholecystitis.

- Marked elevation of serum lipase and/or amylase (>x 4 the upper limit of normal) suggests pancreatitis.

- Prothrombin time (PT), and PT-international normalized ratio.

- Renal function test and electrolytes

- A pregnancy test should be performed in all women of childbearing age.

Imaging

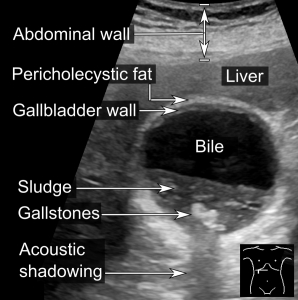

- Gallbladder stones

- Ultrasound is considered the gold standard for detecting gallstones. The sensitivity and specificity of ultrasound for detecting gallbladder stones 2 mm or larger exceeds 95%.

- Finding: Highly reflective echogenic focus within gallbladder lumen, normally with prominent posterior acoustic shadowing regardless of pathological type (acoustic shadowing is independent of the composition and calcium content).

- Differential diagnosis: Gallbladder polyp

- Ultrasound findings consistent with biliary colic due to cholelithiasis include the presence of gallstones or gallbladder sludge without findings of cholecystitis.

- Choledocholithiasis

- Transabdominal ultrasound has a significantly lower utility for choledocholithiasis (sensitivity for choledocholithiasis ~70%).

- However, it more reliably detects biliary ductal dilatation (sensitivity ~65%).

- Sometimes, the characteristics of the gallstones as seen on ultrasound can predict choledocholithiasis. Multiple small (<5mm) stones are associated with a 4-fold higher risk of migration into the common bile duct compared with a single large stone.*

- If no common bile duct stones are visualized on ultrasound, the biliary obstruction can be further investigated with MRCP.

- Acute calculus cholecystitis. (see the media below)

- The most sensitive and specific ultrasound finding in acute cholecystitis is the presence of cholelithiasis in combination with the sonographic Murphy sign.

- The ultrasound findings of acute cholecystitis include:

- Cholelithiasis (~95% sensitivity)

- Cholecystitis is usually caused by stone impaction in the gallbladder neck or cystic duct (an impacted stone won’t move if the patient is repositioned).

- A positive “sonographic” Murphy sign ( ~90% sensitivity)

- Murphy sign has a >95% positive predictive value for acute cholecystitis.

- Keep in mind that this may be absent due to analgesia/obtundation or gangrene of the gallbladder.

- Gallbladder distension (>4 cm transverse measurement, >9 cm longitudinal measurement).

- Secondary signs are relatively non-specific and include

- Gallbladder wall thickening (>4 mm)

- Lack of wall thickening argues strongly against a diagnosis of calculus cholecystitis (high sensitivity).

- GB wall thickening can be caused by many other factors which are common among critically ill patients e.g. ascites, volume overload.

- Pericholecystic fluid or an abscess

- Gallbladder wall thickening (>4 mm)

- Cholelithiasis (~95% sensitivity)

- Cholangitis

-

- Ultrasonographic features suggestive of cholangitis include biliary dilation or evidence of the underlying etiology.

- A hallmark finding is dilation of common bile duct on ultrasound ( specificity ~97%, sensitivity ~65%).

- Remember that dilated bile ducts can be absent either when only small stones are present in the bile ducts or with acute obstruction when the bile duct has not yet had time to dilate.

- The normal measurement limits of common bile duct (CBD) is controversial. However a size >7 mm is probably dilated in most patients. *

- The size of CBD could increase by age (as much as 1 mm per decade after age 60) and also increase as much as 4 mm after cholecystectomy, hence a cut off for dilated CBD in these conditions are

- >6 mm + 1 mm per decade above 60 years of age

- >10 mm post-cholecystectomy *

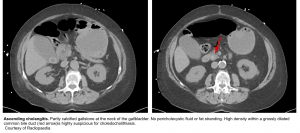

- CT provides a more global imaging of the abdomen. Advantages of CT (to ultrasonography) include identifying:

- Possible co-existent pathologies (e.g. pancreatitis)

- Complications associated with cholecystitis (e.g. perforated gallbladder).

- Causes of biliary stenosis (e.g. pancreatic cancer).

- Bile duct dilation (more sensitive than ultrasound)

- Indications

- Cholecystitis in patients with sepsis (gangrene), generalized peritonitis (perforation), abdominal crepitus (emphysematous cholecystitis), or bowel obstruction (gallstone ileus).

- Suspected cholangitis (CT with IV contrast is the preferred imaging modality).

- Gallbladder stones

- Calcified gallbladder stones are hyperattenuating to bile, making them the only type to be clearly visualized on CT scan images.

- Pure cholesterol stones are hypoattenuating to bile, and other gallstones are isodense to bile and these may not be clearly identified on CT.

- Calculus Cholecystitis

- Possible findings include cholelithiasis, gallbladder distention and wall thickening, pericholecystic stranding and fluid, and high attenuation bile.

- Acalculous cholecystitis

- Diagnosis is highly suggested if either two major criteria, or one major criterion plus two minor criteria are present.

- Major criteria:

- Gallbladder wall thickening >3 mm.

- Subserosal halo sign (intramural lucency caused by edema; equivalent to striated gallbladder on ultrasound).

- Pericholecystic infiltration of fat (“dirty fat”).

- Pericholecystic fluid (in the absence of either ascites or hypoalbuminemia).

- Mucosal sloughing.

- Intraluminal gas (emphysematous cholecystitis).

- Minor criteria:

- Gallbladder distension (>5 cm in transverse diameter).

- High-attenuation bile (sludge).

- Major criteria:

- Diagnosis is highly suggested if either two major criteria, or one major criterion plus two minor criteria are present.

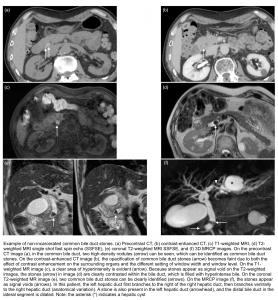

- Choledocholithiasis/ Cholangitis

- Dilation of bile ducts (see the image below).

Magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRI/MRCP)

- MRCP is superior to ultrasound and CT for detecting stones in the cystic duct and common bile duct. See normal MRCP images here.

- Indication:

- MRI/MRCP are used when a diagnosis of concurrent choledocholithiasis in patients with acute cholecystitis and elevations of liver transaminases, total bilirubin, or evidence of common bile duct dilatation on ultrasound are present.

- Stones present as filling defects within the biliary tree on thin cross-sectional T2 weighted imaging (because stones appear as signal void on the T2-weighted images, therefore stones are clearly contrasted within the bile duct, which is filled with hyperintense bile).

Diagnostic criteria

The Tokyo Guidelines for acute cholangitis and acute cholecystitis are widely used and provide evidence-based and consensus-driven diagnostic criteria to support clinical gestalt and management decisions.

- 👉Cholecystitis

- Definite diagnosis requires at least one item in each of three categories

- Systemic signs of inflammation:

- Fever >38°C

- Shaking chills

- WBC count <4,000 or >10,000.

- Elevated CRP > 10 mg/L (or other changes suggestive of inflammation).

- Local signs of inflammation

- Murphy’s sign

- Right upper quadrant pain, mass, or tenderness

- Imaging findings characteristic of acute cholecystitis

- Systemic signs of inflammation:

- Definite diagnosis requires at least one item in each of three categories

- 👉Cholangitis

- Definite diagnosis requires at least one item in each of three categories

- Evidence of systemic inflammation (any of the following)

- Fever or rigors

- WBC count <4,000 or >10,000.

- Elevated CRP>10 mg/L (or other changes suggestive of inflammation).

- Laboratory evidence of cholestasis (any of the following)

- Total bilirubin >2 mg/dL.

- Elevated alkaline phosphatase, AST, or ALT (above 1.5 times the upper range of normal).

- Imaging with biliary dilation or evidence of the underlying etiology (e.g. a stricture, stone, or stent).

- Evidence of systemic inflammation (any of the following)

- Definite diagnosis requires at least one item in each of three categories

Complications

Cholecystitis

Cholecystitis is usually self-contained. The disease process is usually limited to the gallbladder and patients more often respond to medical management. Rarely the course of the disease is progressive and following complications may occur.

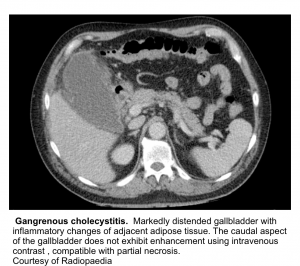

- Gangrenous cholecystitis (~20%)

- It occurs as a result of ischemia with necrosis of the gallbladder wall.

- Risk factors: elderly, diabetes, or those who delay seeking therapy.

- Clinical presentation:

- The presence of a sepsis like picture in addition to the other symptoms of cholecystitis.

- Progressive symptoms and signs such as high fever, hemodynamic instability, or intractable pain in spite of best supportive care (including antibiotics and gallbladder drainage) indicate disease progression, which is a sign of gallbladder gangrene.

- US: In addition to features of acute cholecystitis, the following may help diagnose gangrenous cholecystitis (see media below):

- Intraluminal membranes

- Asymmetrical wall thickness

- Sonographic Morphy sign is invariably absent (attributed to ischemic denervation of the gallbladder).

- CT: lack of enhancement of the gallbladder wall following IV contrast indicates gangrenous tissue.

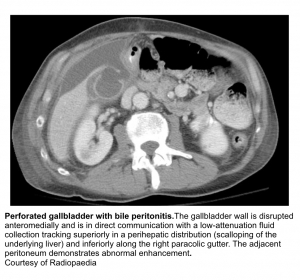

- Perforation

- It occurs in patients with a delay in diagnosis or failure to respond to initial therapy.

- Symptoms and clinical signs are variable and can range from benign non-specific abdominal symptoms to acute generalized peritonitis.

- The perforation is often localized after the development of gangrene, resulting to pericholecystic abscess. Less commonly, there is free perforation into the peritoneum, leading to generalized peritonitis and associated with a high mortality.

- US: Pericholecystic fluid collection(s) with layering of the gallbladder wall.

- Defect or bulge in the gallbladder wall

- Pericholecystic fluid collection

- Stranding of the omentum or mesentery

- Layering of the gallbladder wall

- CT: Superimposing on background cholecystitis, CT may show:

- Defect or bulge in the gallbladder wall

- Layering of the gallbladder wall

- Pericholecystic fluid collection(s)

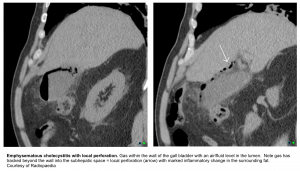

- Emphysematous cholecystitis

- Is a rare form of complicated cholecystitis where gallbladder wall necrosis causes gas formation in the lumen or wall.

- It is a surgical emergency, due to the high mortality from gallbladder gangrene and perforation.

- Clinical manifestation is often insidious and may then progress rapidly. Up to ~25% of patients may be afebrile and localized tenderness is often not a dominant clinical feature.

- CT is considered the most sensitive and specific imaging modality for identifying gas within the gallbladder lumen or wall.

Cholangitis

- The most common complications of acute cholangitis include acute pancreatitis (7.6% of cases), liver abscess (2.5%), and endocarditis (up to 0.26%).

- Other frequent complications are:

- Bacteremia, sepsis and septic shock

- Bacteria under pressure spread readily up bile ducts, across hepatic sinusoids, and into the blood. This physiology generates characteristic bacteremia and shaking chills.

- Cholangitis has a greater tendency to evolve rapidly into septic shock ( compared to calculous cholecystitis).

- Multiple organ system dysfunction

- Portal vein thrombosis

- Gastrointestinal bleeding

- Bacteremia, sepsis and septic shock

Severity assessment for acute cholecystitis and cholangitis

The 2018 Tokyo Guidelines also provide a grading system for severity of cholangitis and cholecystitis.

Grade III (Severe): Diagnosis of cholecystitis or cholangitis + any ONE of the following findings of associated organ dysfunction:

-

Hypotension requiring dose of norepinephrine ≥5 μg/kg/min

-

Altered mental status

-

PaO2/FiO2 <300

-

Oliguria or serum creatinine >2.0 mg/dL

-

INR >1.5

-

Thrombocytopenia <100,000/mm3

Grade II (Moderate)

- Cholecystitis + any ONE of the following:

- WBC count >18,000/mm3

- Palpable tender RUQ mass

- Length of illness >72h

- Severe local inflammation:

- Gangrenous cholecystitis

- Pericholecystitic abscess

- Hepatic abscess

- Biliary peritonitis

- Emphysematous cholecystitis

- Cholangitis + any TWO of the following:

- WBC >12 or <4 (×1,000/mm3)

- Fever ≥39°F

- Age ≥75 y

- Total Bili ≥5 mg/dL

- Hypoalbuminemia (<0.7 × Lower limit of normal)

Grade I (Mild)

- Diagnosis of cholecystitis or cholangitis with NO criteria of Grade II (Moderate) or Grade III (Severe) disease.

Treatment

Supportive care

Make the patient NPO and administer IV fluids and analgesic

- Fasting (NPO) avoids the endogenous release of cholecystokinin, which can further stimulate gallbladder contraction and pain.

- Pain control can be achieved with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or opioids (both are equally effective) *.

- Progression of pain despite adequate analgesia indicates clinical progression of disease, which may necessitate interventions such as surgery or gallbladder drainage in high-risk patients.

Antibiotics

- General consideration

- Empiric IV antibiotic is based on the disease severity, and risk factors associated for severe intra-abdominal infection:

- Age >70 years

- Comorbidity (e.g. renal or liver disease, presence of malignancy).

- Immunocompromised state (e.g. poorly controlled diabetes, chronic high-dose corticosteroid use, use of other immunosuppressive agents, neutropenia, advanced HIV infection)

- Healthcare-acquired infection

- Known colonization with antibiotic-resistant organisms.

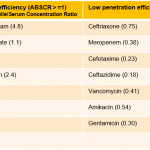

- Biliary penetration of antibiotics.

- This is probably most relevant for ascending cholangitis. In cholecystitis, bile doesn’t come in contact with the focus of infection within the gallbladder, so biliary penetration is not probably important (see appendix 1).

- Dose adjustment for impaired renal function should be considered.

- Coverage: When empiric antibiotic therapy is indicated, the chosen agent(s) should cover the most common pathogens listed below.

- Empiric IV antibiotic is based on the disease severity, and risk factors associated for severe intra-abdominal infection:

- Organisms isolated from bile of patients with acute biliary infection

- Gram negatives are the most common and important pathogens

- E. coli (25-50%)

- Klebsiella spp. (15-20%)

- Enterobacter spp. (5-10%)

- Pseudomonas spp. (0.5-19%)

- Gram positives

- Enterococcus spp. (10-20%)

- Streptococcus spp. (2-10%)

- Anaerobes, including Bacteroides fragilis (4-20%)

- Gram negatives are the most common and important pathogens

- Tips on involved microbes

- The pathogenic role of anaerobes is unclear. Anaerobes should be covered in patients with a biliary-enteric anastomosis or gangrenous/emphysematous cholecystitis.

- Anti-anaerobic agents, include metronidazole or clindamycin. The carbapenems, piperacillin/tazobactam, ampicillin/sulbactam, cefoxitin, and cefoperazone/sulbactam have sufficient anti-anaerobic activity for this situation as well.

- MRSA is not a community-acquired biliary pathogen.

- Thus, there is no role for vancomycin in community acquired cholecystitis or cholangitis.

- Indications to add vancomycin (or linezolid if VRE is known to be colonizing the patient, if previous treatment included vancomycin):

- Healthcare acquired biliary sepsis.

- Grade III (sever) community acquired cholecystitis or cholangitis.

- If the blood cultures reveal gram positives.

- The pathogenic role of anaerobes is unclear. Anaerobes should be covered in patients with a biliary-enteric anastomosis or gangrenous/emphysematous cholecystitis.

- Empiric IV antibiotic

- Mild: First- to third-generation cephalosporins (e.g. cefotaxime , Ceftriaxone) or fluoroquinolone (Ciprofloxacin , Levofloxacin)

-

- 👉If biliary-enteric anastomosis, consider additional anaerobic coverage with Metronidazole.

-

- Moderate: Piperacillin/tazobactam

- Severe: piperacillin-tazobactam or Meropenem plus Vancomycin.

- Mild: First- to third-generation cephalosporins (e.g. cefotaxime , Ceftriaxone) or fluoroquinolone (Ciprofloxacin , Levofloxacin)

- Duration of therapy

- By enlarge the duration of antibiotic therapy is generally tailored to the clinical situation.

- Once the source of infection is controlled, antimicrobial therapy for patients with biliary sepsis is continued for an additional duration of four to five days.

- If the source has been surgically removed (cholecystectomy), then shorter courses of antibiotics may be adequate.

Interventional therapy

Acute cholecystitis

- Emergent cholecystectomy may be indicated in the following conditions:

- Gallbladder perforation.

- Emphysematous cholecystitis.

- Gangrenous/necrotic cholecystitis.

- Percutaneous cholecystostomy

- This is the intervention of choice in patients with “acalcolous cholecystitis” to provide drainage of biliary tract, unless complications of cholecystitis e.g. emphysematous cholecystitis, perforation, necrotic cholecystitis develop.

- If patient does not improve within 24-48h, surgical cholecystectomy should be considered.

Acute cholangitis

- Therapeutic ground

- Relief of the biliary obstruction is a critical intervention for ascending cholangitis, as this allows pus to drain out of the biliary tree.

- Prompt drainage of the biliary system provides source control for acute cholangitis thereby decreasing bile and serum endotoxin levels in addition to promoting the biliary excretion of IgA and antibiotics.

- The 2018 Tokyo Guidelines recommend urgent/emergent (performed < 48h) biliary drainage for moderate and severe cholangitis.

- Biliary drainage is only recommended in mild acute cholangitis if there is no response to antibiotics.

- Methods:

- Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)

- ERCP remains the gold standard for biliary decompression with success rate of > 90% of cases of cholangitis.

- It allows for stone removal as well as procedures to keep the bile ducts open (sphincterotomy and/or stent placement).

- The only absolute contraindication to ERCP is known or suspected viscus perforation.

- Complications (~5%)

- Pancreatitis (~5%)

- Hemorrhage (~2%)

- Perforation leading to pneumoperitoneum

- Infection (e.g. cholangitis)

- Migration of a biliary or pancreatic duct stent

- Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)

- Percutaneous Transhepatic Cholangiography (PTC)

- PTC is generally considered a second-line drainage option, either after a failed ERCP, in patients with multiple comorbidities, or in patients with surgically altered anatomy not amenable to endoscopic therapy (e.g. patients who are status post gastric bypass).

Going further

Media

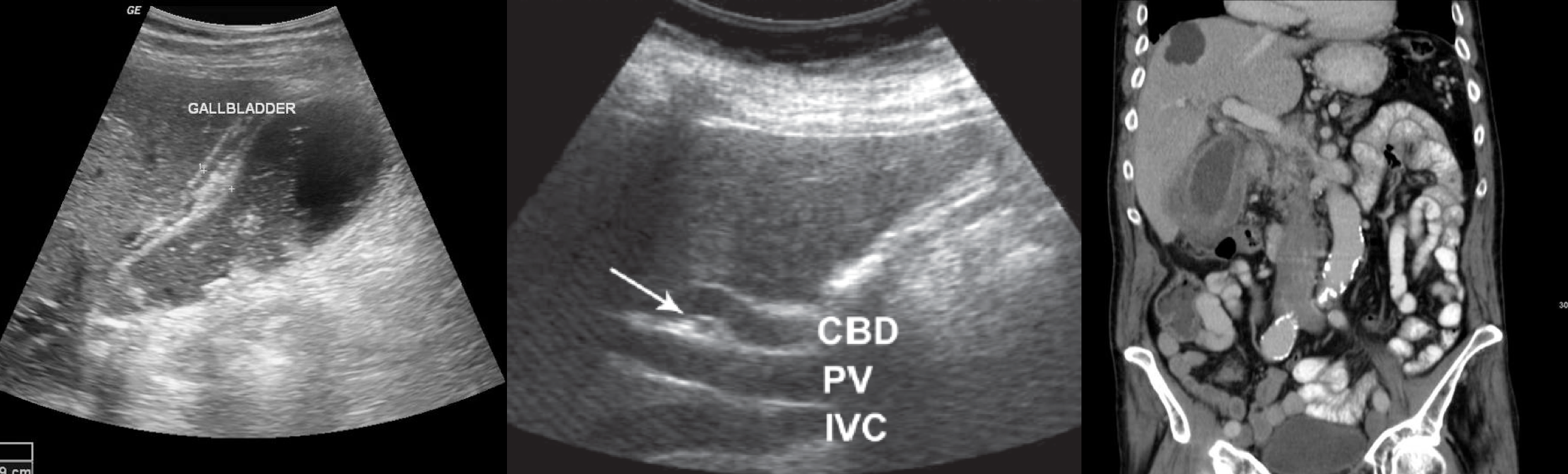

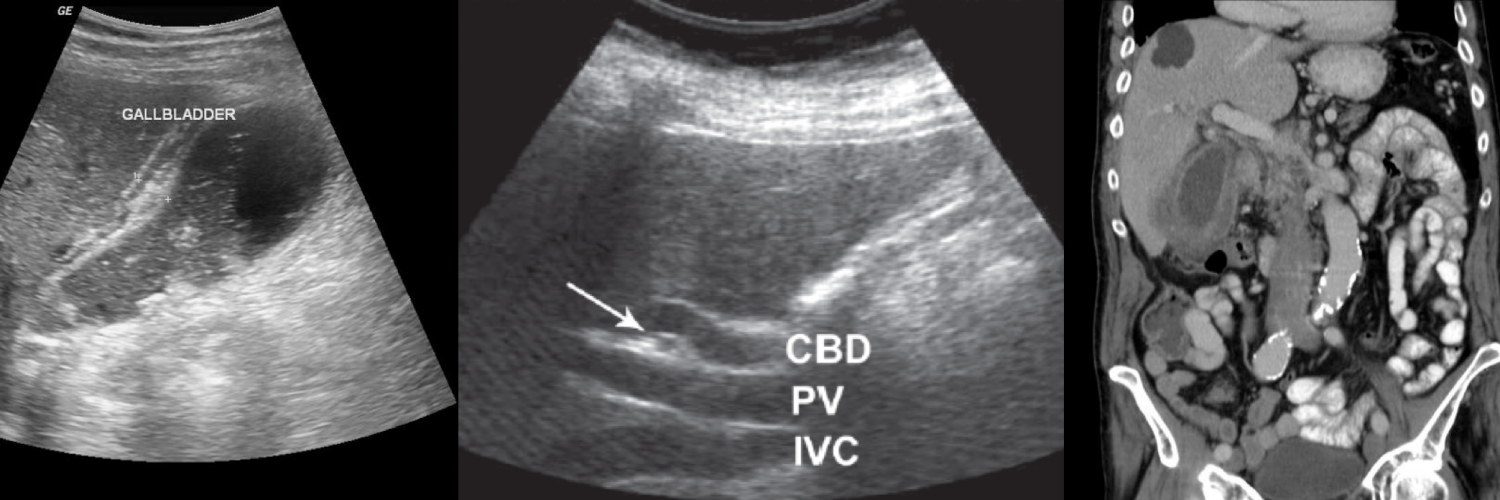

Locating the common bile duct with ultrasound

Troubleshoot the CBD on ultrasound

Add comment