December 25, 2020 by Shahriar Lahouti. Last update 12 September 2023.

CONTENTS

- Preface

- AV anatomy

- Aortic regurgitation

- Differential diagnosis

- Bedside echocardiography

- Management

- Multiple and Mixed Valvular Heart Disease

- Going further

- Reference

2D, two-dimensional

ACC,American college of cardiology

ACS, acute coronary syndrome

AF, atrial fibrillation

ASE,American Society of Echocardiography

AV, aortic valve

AR, aortic regurgitation

AS, aortic stenosis

BAV, Bicuspid aortic valve

CM, cardiomyopathy

CWD, Continuous wave Doppler

CFD, color flow Doppler

EAE, European Association of Echocardiography

EF, ejection fraction

EROA, Effective regurgitant orifice area

LA, left atrium

LAE, left atrial enlargement

LAP, left atrial pressure

LV, left ventricle

LVE, left ventricle enlargement

LVOTO, left ventricular outflow tract obstruction

MV, mitral valve

MS, mitral stenosis

MR, mitral regurgitation

MVP, mitral valve prolapse

PAP, pulmonary arterial pressure

PLAX, parasternal long-axis

PSAX, parasternal short axis

PH, pulmonary hypertension

POCUS, point of care ultrasound

RA, right atrium

RV, right ventricle

TTE, transthoracic echocardiography

TEE, transesophageal echocardiography

TV, tricuspid valve

TR, tricuspid regurgitation

VHD, valvular heart disease

VC, Vena contracta

VCA, Vena contracta area

VCW, Vena contracta width.

Preface

In this series of valvular emergencies, the identification of life-threatening native valvular lesions in the emergency department is explored. Patients with aortic regurgitation can present with cardiorespiratory failure and a timely diagnosis and treatment is potentially crucial. Four essential questions should be considered when screening for valvular dysfunction by echocardiography in undifferentiated cardiorespiratory failure:

- Is there a “severe” valvular dysfunction (in this case ‘severe AR)?

- In the presence of acute severe AR, what could be the possible etiology?

- Does this explain my patient’s clinical presentation?

- How has this finding changed my management plan?

Aortic Valve Anatomy

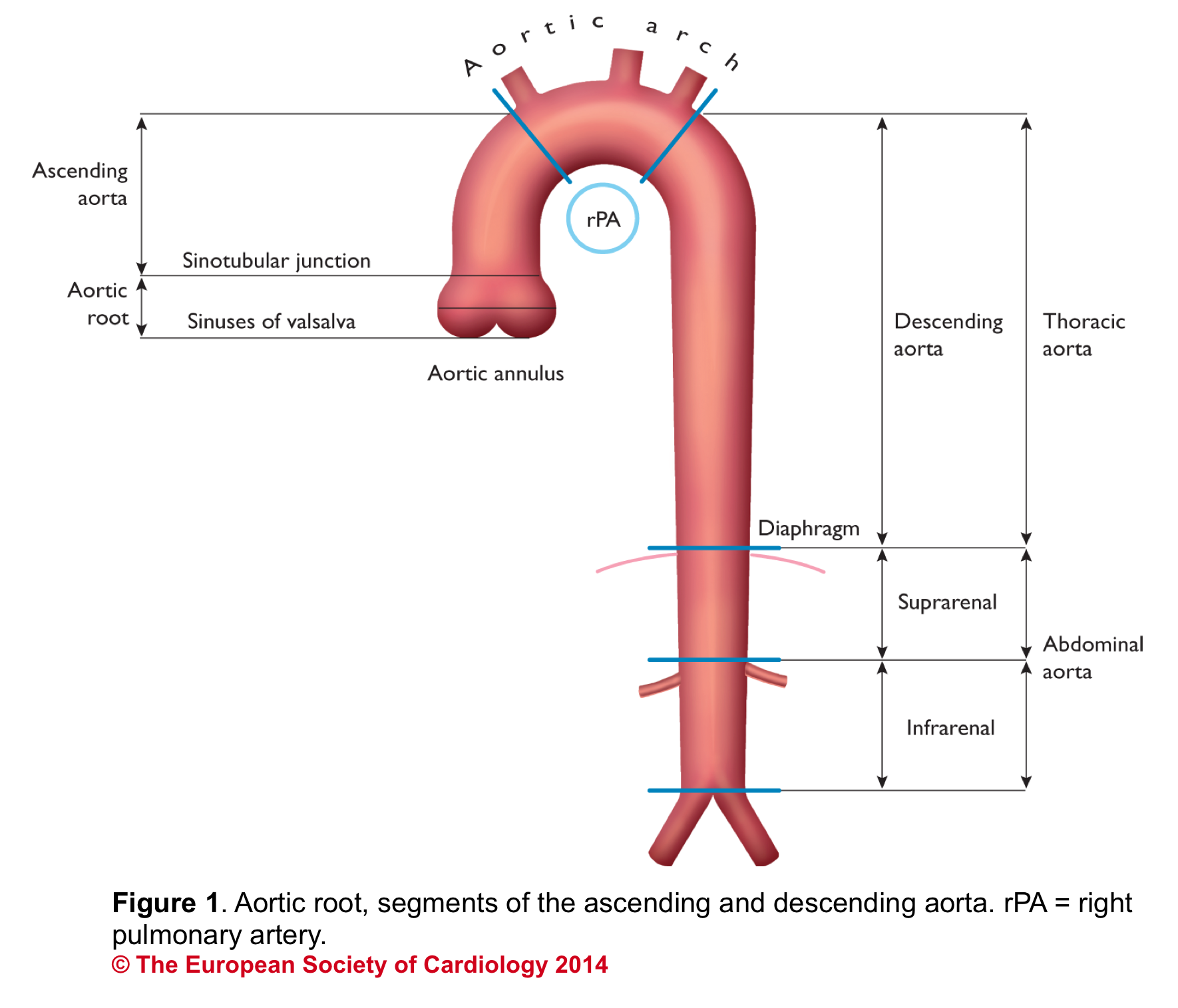

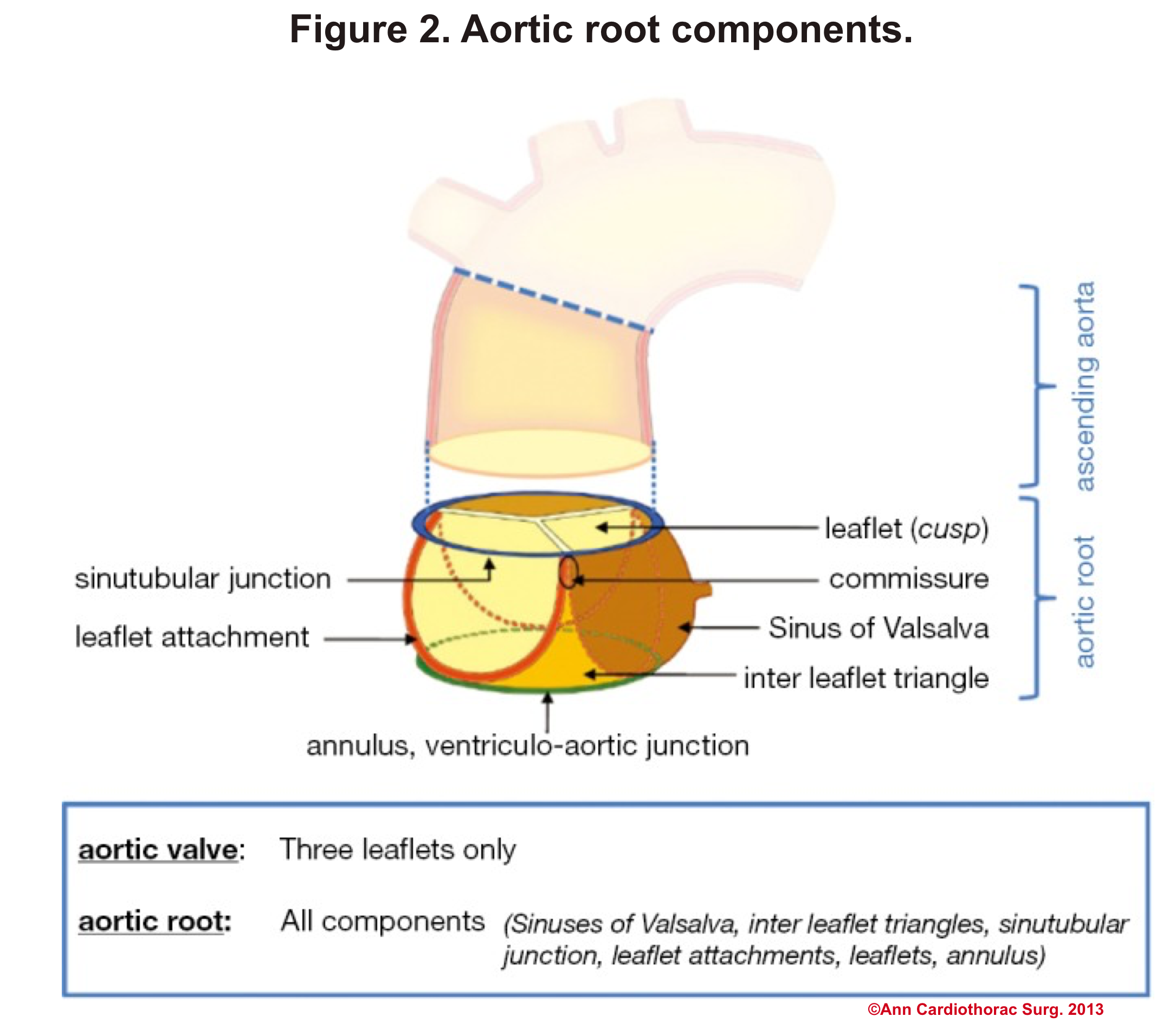

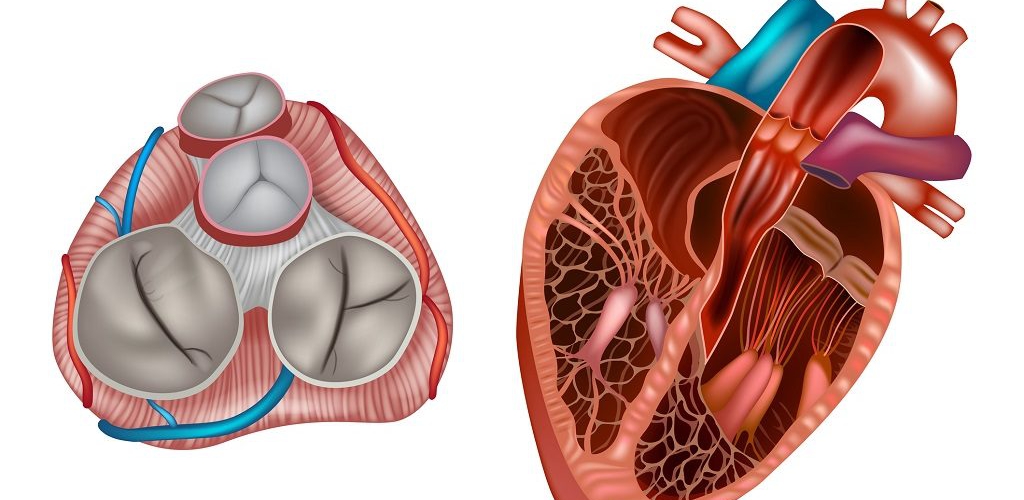

Aortic Root: Is a complex structure that connects the heart to the systemic circulation (figure 1). Distinct anatomical structures come together and make the aortic root (figure 2)*.

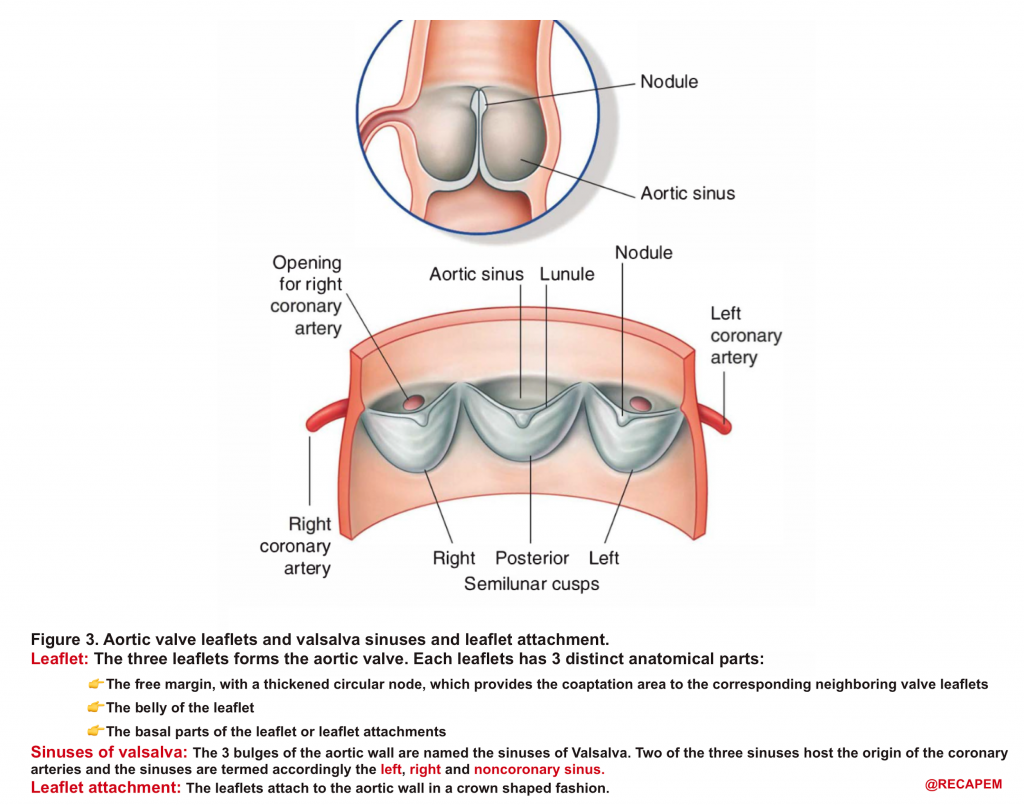

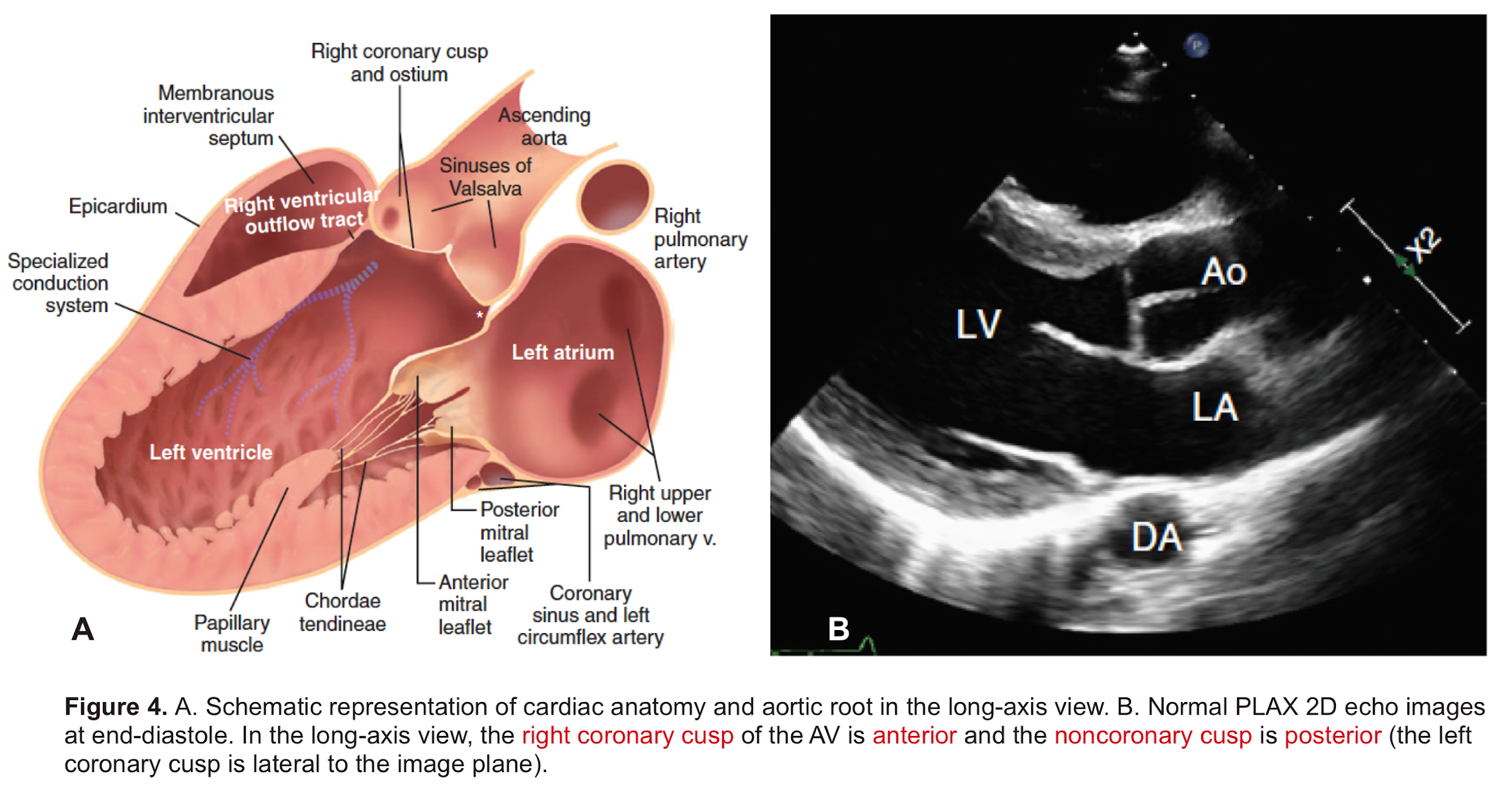

- AV leaflets: The three leaflets form the aortic valve. Each leaflet has 3 distinct anatomical parts shown below (figure 3). The echocardiographic representation of AV leaflets in PLAX is shown below (figure 4).

- Sinuses of Valsalva: The three bulges of the aortic wall are named the sinuses of Valsalva (figure 3)

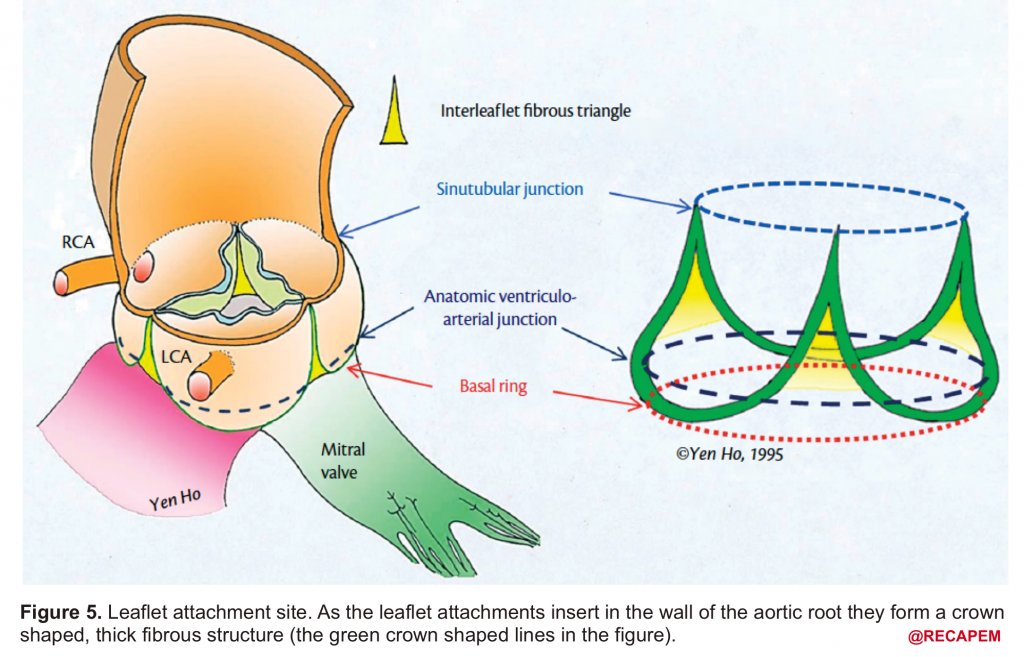

- Leaflet attachment: The leaflets attach to the aortic wall. At the site of their attachments, they form a crown-shaped thick fibrous structure called an annulus (figure 5)

Sinotubular junction (STJ): The distal part of the sinuses toward the ascending aorta together with the commissures form a tubular structure called the “sinotubular junction” which separates the aortic root from the ascending aorta(Figure 1,5).

Bicuspid aortic valve (BAV)

- BAV is the most common congenital heart defect, with a prevalence estimated between 0.5% and 2%.

- There is a male predominance of approximately 3:1.*

- The bicuspid valve is typically made of 2 unequal-sized leaflets. The larger leaflet has a central raphe or ridge that results from the fusion of the commissures.

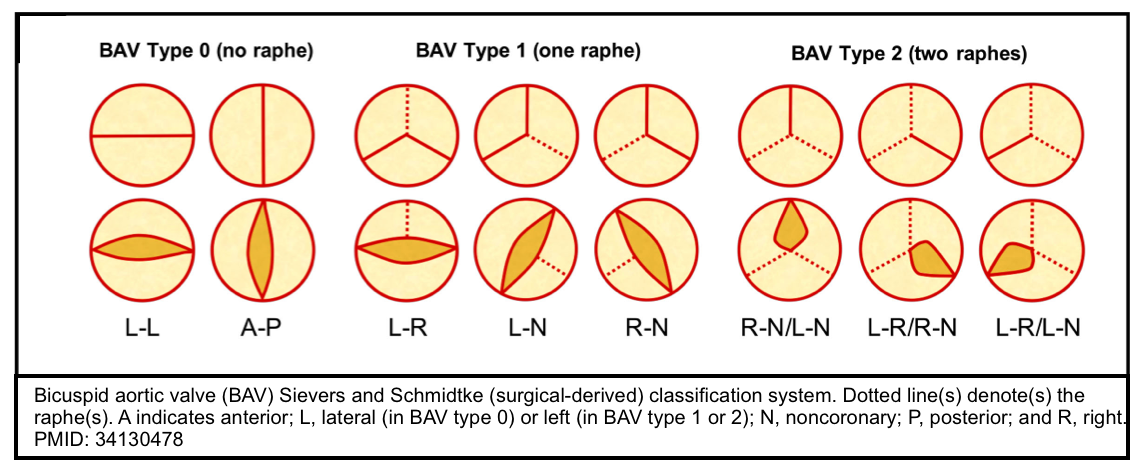

- The morphologic patterns of the bileaflet valve vary according to which commissures have fused, with the most common pattern involving the fusion of the right and left cusps. Fusion of the right and left coronary cusps is associated with coarctation of the aorta. Fusion of the right and noncoronary cusps is associated with cuspal pathology. Rarely, the leaflets are symmetrical or there is no raphe (“pure” bicuspid valve). A number of classifications have been used that pertain to the orientation of the leaflets *.

Echocardiography of BAV

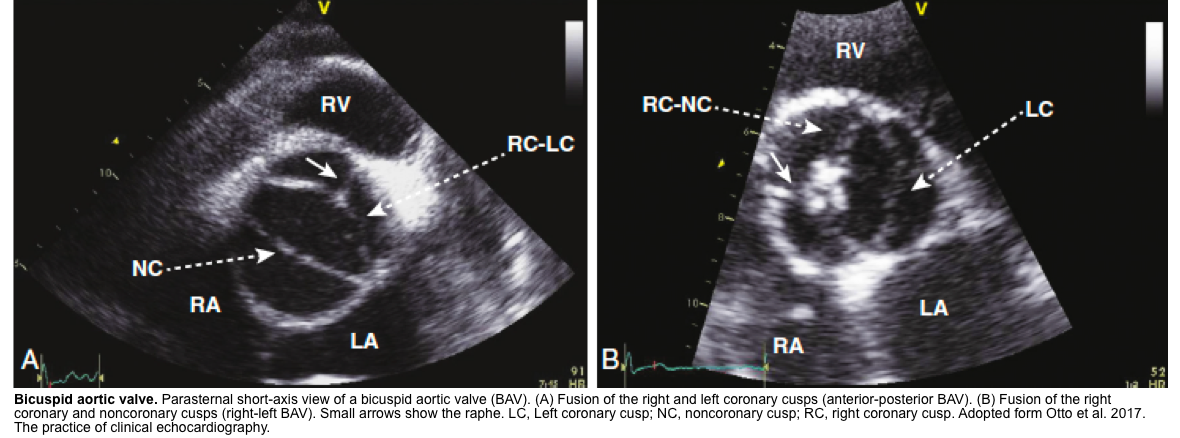

- BAV on short axis TTE give a clam-shell like systolic opening pattern, rather than the pie-shaped peeling-back of the normal valve.

Aortic Regurgitation

Definition: AR is caused by inadequate closure of AV leaflets which results in backflow of the blood into the LV during diastole.

Clinical presentation

The clinical presentation of AR depends on multiple factors including mechanism, etiology, and “severity” of AR, as well as course of the disease (rate of progression) and presence of other coexisting cardiac disease.

- Severe acute AR commonly presents with signs of hemodynamic instability (dyspnea, syncope, or altered mental status) or frank cardiogenic shock. Other presenting symptoms are related to the cause of acute AR (e.g., signs and symptoms of aortic dissection or endocarditis)

- Patients with aortic dissection can present with a myriad of symptoms such as sudden onset of pain (chest/back/abdomen), syncope (due to the development of tamponade), and focal neurologic deficit (more on this here).

- Patients with chronic AR may remain asymptomatic for decades, even if there is progressive ventricular dilation. Symptoms that develop in some patients with severe AR (stage D) include exertional dyspnea, angina, and other symptoms of heart failure

Mechanism and etiology of AR

Aortic regurgitation can be induced either by disease of the AV leaflets or by distortion or dilation of the aortic root and ascending aorta.

Background

- Bicuspid aortic valve

- The aortic valve (AV) has 3 leaflets. This trileaflet design represents the optimal solution for low-resistance valve opening and no other valve configuration can provide these characteristics. This fact is demonstrated in the setting of a bicuspid aortic valve, in which some kind of valve dysfunction or degree of stenosis always co-exists depending on the configuration *.

- AV function is not affected by the left ventricle (LV).

- AV leaflets are attached to the aortic root. In contrast to mitral valve (MV) leaflets which are bounded by annulus, there’s no such a distinct histological entity or anatomical boundary in AV *. Moreover, the AV is a mechanically passive valve. The absence of muscular structures with supporting strings (such as for MV), makes AV less structurally dependent on the LV. This has hemodynamic implications:

- While LV disease such as cardiomyopathy can cause LV enlargement and secondarily impacts MV function resulting in MR; such a relation is not often true for AV. That is to say, “AV function is not influenced by LV dysfunction“.

- AV function is rather more influenced by upstream conditions such as hypertension which can cause aortic root enlargement and results in AR.

- AV leaflets are attached to the aortic root. In contrast to mitral valve (MV) leaflets which are bounded by annulus, there’s no such a distinct histological entity or anatomical boundary in AV *. Moreover, the AV is a mechanically passive valve. The absence of muscular structures with supporting strings (such as for MV), makes AV less structurally dependent on the LV. This has hemodynamic implications:

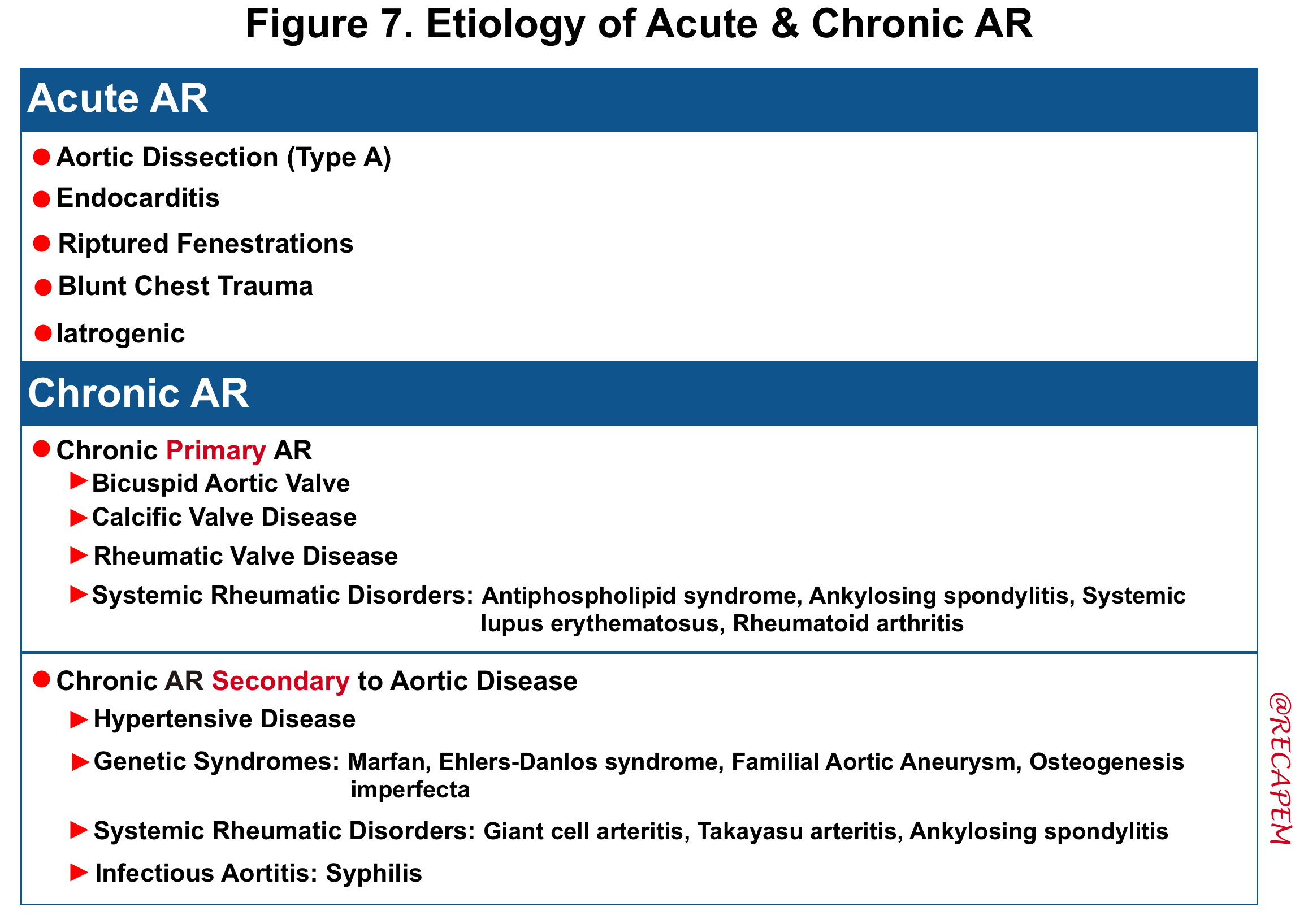

Etiology

- The etiology of acute and chronic AR are summarized in the following table.

- Acute AR: The causes of acute AR with a native aortic valve are limited and include:

- Endocarditis

- Endocarditis leads to AR due to leaflet destruction or peri-aortic valvular abscess rupture.

- Aortic dissection

- Aortic dissection can lead to AR through a variety of mechanisms, including extension of the dissection flap into the valve, involvement of a valve commissure that may result in inadequate leaflet support, dilation of the sinuses leading to incomplete coaptation of the leaflets, and/or prolapse of the dissection flap across the aortic valve, which impedes valve closure.

- Note that patients with BAV are at higher risk of aortic dissection.

- Aortic dissection can lead to AR through a variety of mechanisms, including extension of the dissection flap into the valve, involvement of a valve commissure that may result in inadequate leaflet support, dilation of the sinuses leading to incomplete coaptation of the leaflets, and/or prolapse of the dissection flap across the aortic valve, which impedes valve closure.

- Rupture of a congenitally fenestrated cusp.

- Traumatic rupture of the valve leaflets. It can occur after deceleration injury or blunt trauma to the chest

- Iatrogenic: Complication of procedures such as aortic balloon valvotomy or transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI).

- Endocarditis

Severity of AR

The essential component of bedside evaluation of VHD in ED is to determine the severity of the disease. The patient’s tolerance to AR is contingent upon the acuteness of the process and severity of the AR among the list.

- The course of the disease and rate of progression

- An acute severe AR is usually a medical emergency and is not tolerable.

- In contrast to chronic regurgitation which affords time for the left ventricle to dilate and accommodate the regurgitant flow, in acute regurgitation the lack of time for adaptation to additional blood volume leads to an acute increase in LV diastolic pressure and a fall in forward cardiac output.

- An acute severe AR is usually a medical emergency and is not tolerable.

- Underlying substrate and presence of other cardiovascular disease

- Patients with small non-compliant LV (e.g. concentric LVH) due to pre-existing conditions such as systemic hypertension are prone to acute changes in pressure and flow seen in acute AR and will develop more profound signs and symptoms following acute AR.

Hemodynamic impact of AR

💡The burden of AR on the heart is volume overload.

Acute AR

- The regurgitant volume fills the small LV, resulting in an acute increase in LV end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP) and a fall in forward cardiac output *.

- ⬆️LVEDP (LVEDP >LAP in late diastole)

- In severe AR, the left ventricle accepts blood not only from the left atrium but also from the aorta during diastole.

- Thus, the AR ‘overfills’ the LV and makes the LVEDP rapidly increase and possibly exceed the LA pressure (LAP) in late diastole. This has the following consequences:

- Early closure of mitral valve. This impedes the transient opening of MV by atrial contraction, adds to LA volume overload, and aggravates pulmonary edema *.

- Diastolic mitral regurgitation (DMR). If AR is acute and severe, the elevated LVEDP is so high that may cause a diastolic MR. It will aggravate LA overloading and worsen pulmonary edema.

- DMR in severe AR (video below) indicates the acuteness of AR and the need for urgent surgical intervention, while DMR in itself is a reversible process as it will disappear after successful aortic valve replacement *.

- DMR has been shown to be an independent predictor of decompensation in patients with acute AR due to endocarditis. These patients should be considered for emergent surgery *.

- ⬇️Forward flow leads to hypotension and cardiogenic shock.

- Early closure of the MV (due to high LVEDP) and tachycardia (related to a compensatory response to shock) both contribute to the shortening of diastolic filling time and may exacerbate the decline in forward flow.

- ⬆️LVEDP (LVEDP >LAP in late diastole)

Severe aortic regurgitation with DMR.Quan Li et al. 2020. European Heart Journal. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjcr/ytaa203

Chronic AR

- The left ventricle adapts over time to volume overload by the development of LV enlargement (compensatory eccentric hypertrophy)and therefore is able to adapt to changes in pressure (LVEDP remains normal). This adaptive response will keep forward flow (cardiac output) within the normal range *, *.

- 👉Notably, acute exacerbation of chronic regurgitation may result in similar hemodynamic changes explained in acute AR above..

Differential diagnosis

- Patients with acute moderate-severe AR or those with acute exacerbation of chronic AR present with acute pulmonary edema or cardiogenic shock.

- Importantly patients may present with signs and symptoms of underlying cause of AR (e.g. fever in endocarditis, and chest/back pain or syncope in aortic dissection).

- Patients with acute AR due to aortic dissection can have extension into the right coronary artery and therefore may have ECG changes consistent with an acute inferior myocardial infarction.

- 🔴Always consider aortic dissection in unstable patients with acute aortic regurgitation.

Bedside echocardiography

Scope of the examination

The qualitative and semi-quantitative method is an adapted time-saving approach to diagnose severe native valve AR in ED and it incorporates 2D, CFD, and PWD echocardiography which are explored below *, *, *, *.

Examination technique

2D exam

- Try to get a focused window of the interested valve (AV) in multiple views.

- First focus on aortic root size and the presence of a dissection flap in the PLAX view.

- Aortic root

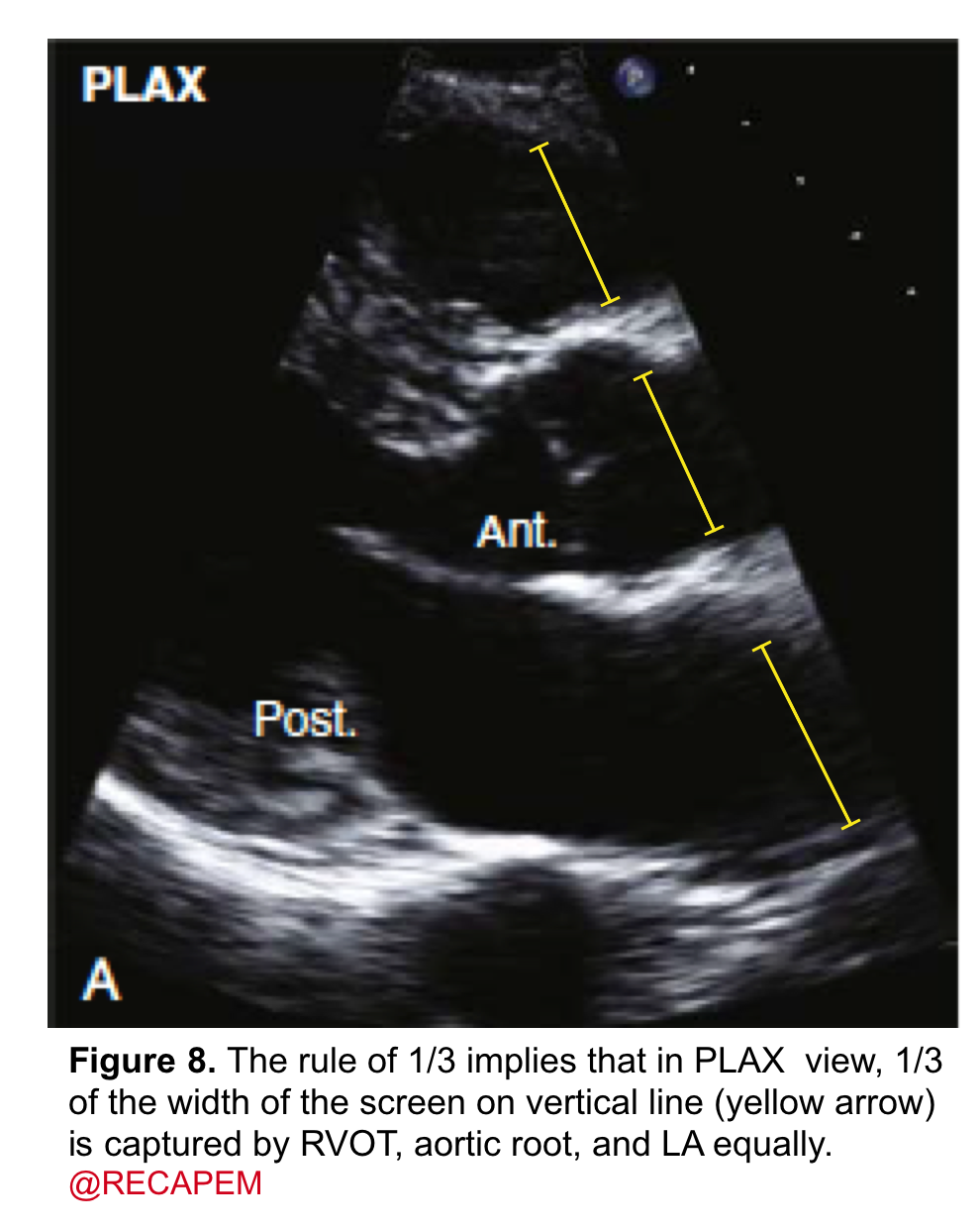

- It can be assessed qualitatively by eyeball. The rule of ⅓ implies that in the PLAX view, ⅓ of the width of the screen on a vertical line is captured by the RV outflow tract, aortic root, and left atrium equally (figure 8).

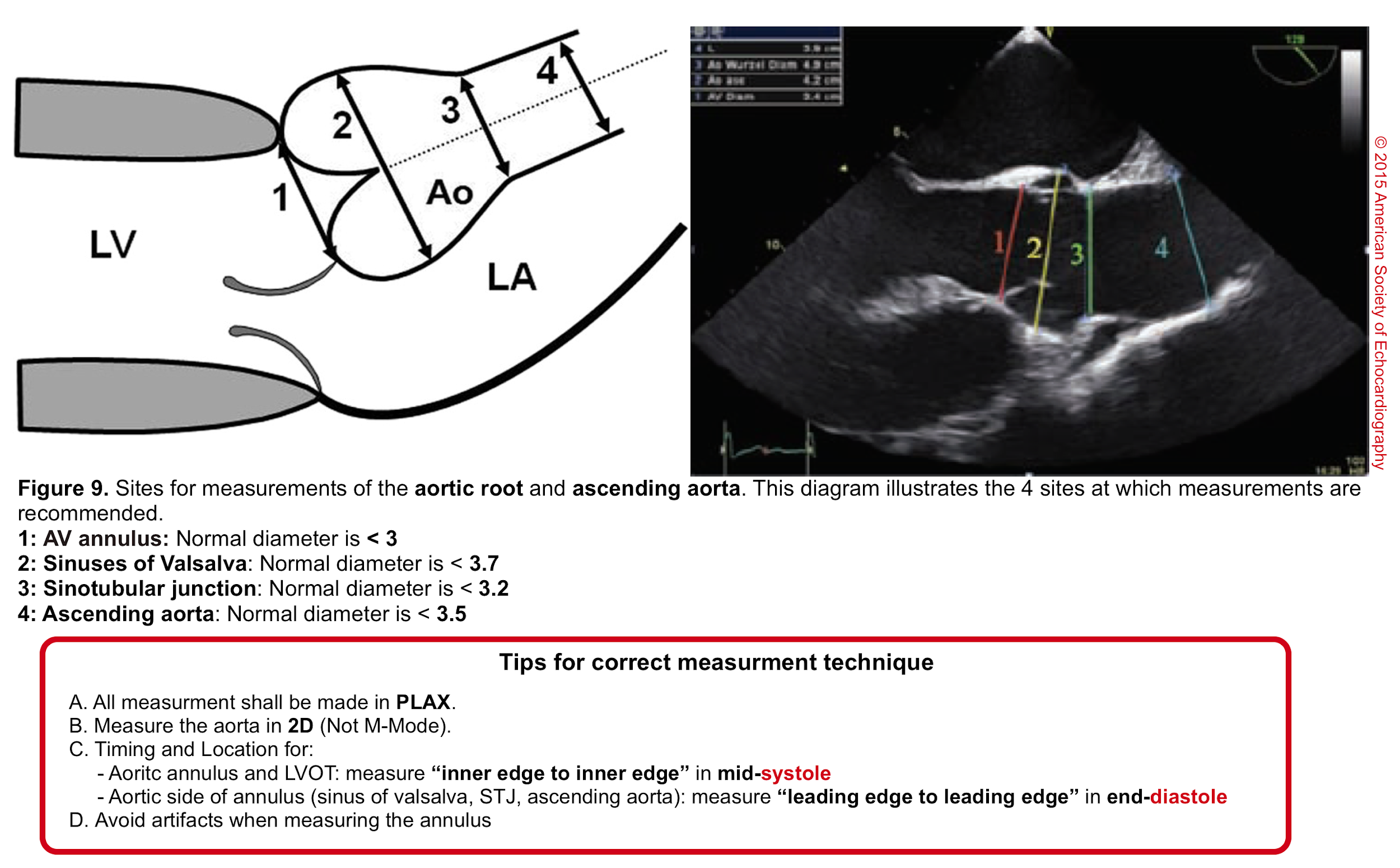

- Aortic root can be measured quantitatively at different levels (figure 9).

- Dissection (intimal) flap

- The presence of an intimal flap is a direct sign of aortic dissection though sometimes visualizing the flap is not easy. (more on this here)

- Aortic root

- Second: focus on AV leaflet morphology and motion which are usually best seen in the PLAX and PSAX view at the level of the aortic valve. Pay specific attention and look for:

- Leaflet morphology

- Leaflet thickening

- Calcifications

- Vegetation (figure10)

- Perforation

- Presence of BAV

- Leaflets motion

- Valve coaptation defect

- Flail leaflets

- Leaflet morphology

- Other echocardiographic data which can be discerned in 2D

- LV/LA size, LV systolic function, LVhypertrophy.

- Keep in mind the indirect signs of aortic dissection on 2D echo are discernible as * :

- Dilatation of the aortic root

- Compression of the LA

- Pericardial and/or pleural effusion

Fig 10. Aortic valve endocarditis and vegetation

| Other interesting finding in patients with AR on 2D echo 🟠Acute severe AR may cause severe ↑LVEDP→Early closure of mitral valve and/or “functional diastolic MR”(explained above). 🟠Severe AR may cause “Fluttering” of anterior leaflet of mitral valve (echocardiographic sign of Austin flint murmur) or “IVS” in diastole. 🟠Severe AR may cause reverse doming of mitral leaflet in diastole |

What happens to the anterior mitral leaflet in this young patient evaluated for syncope? #POCUS @Mms05333272 @Arualemon @DaBiT_9 @curromir @DiazgomezA @JMMR83 @NephroP @GTECOSEMI @ecovallhebron @yaletung @jtorresmacho @200julios @The_echo_lady pic.twitter.com/WlCvlTczgA

— Medicina Interna. Lo miro y mañana te digo. (@y_interna) June 28, 2023

Why am I hearing a mid Diastolic murmur at the apex(mitral area) in this patient? What exactly is the mechanism? pic.twitter.com/kmZ5govUrc

— Dr G Rajesh (Gopalan Nair Rajesh) (@DrRajeshG1) August 4, 2023

#echofirst case solution. Severe AR due to BAV (prolapse RCC) with jet directed su AML with pseudo prolapse A2 (called like that?). LV Dilatation more suitable with AR then with MR as LV EF isn't depressed. Grading done using SV LVOT & RVOT, looking at DA. PML hypoplastic. pic.twitter.com/bVTkSzPZiU

— Nicolas Merke (@NMerke) August 4, 2023

CFD exam

- Clinical usefulness

- Diagnosis of AR by identifying the regurgitant flow of AR (figure 11).

- AR in most patients is easily seen with CFD as a mosaic blend of colors originating from the AV during diastole. Although the apical approach is the most sensitive for the detection of AR (even mild AR can be visualized), the PLAX is OK in the ED, since the goal of screening for valvular disease in the ED is to identify ‘severe’ valvular dysfunction.

- Determining severity of AR

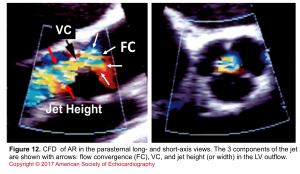

- Assessment of components of the jet (jet area, VC, and flow convergence). Figure 12

- Direction of regurgitant flow

- Differentiating false lumen from true lumen of aortic dissection with intimal flap.

- Diagnosis of AR by identifying the regurgitant flow of AR (figure 11).

Figure 11. CDF in PLAX view showing regurgitant flow through aortic valve

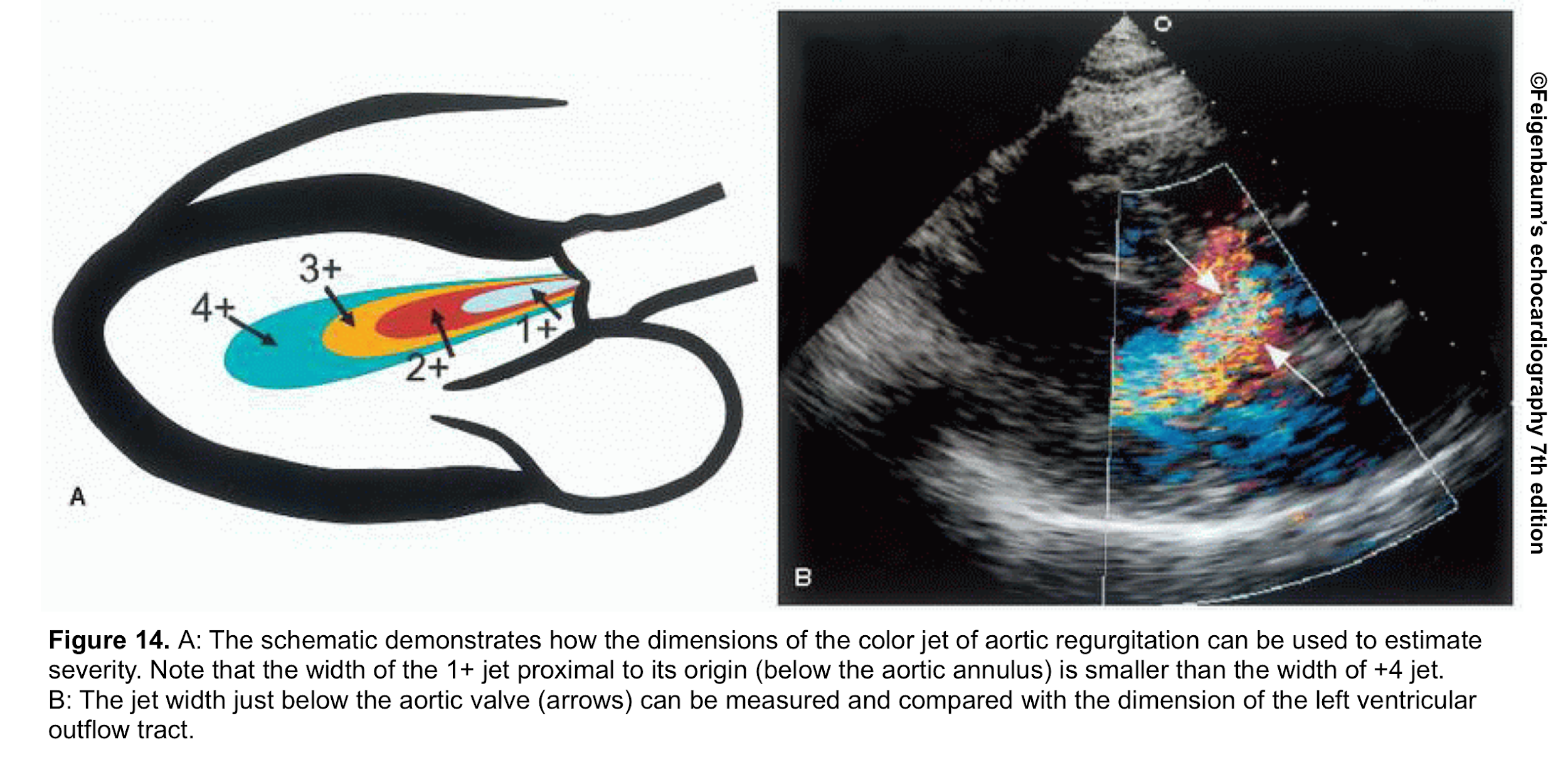

- Jet width in LV outflow tract (LVOT)

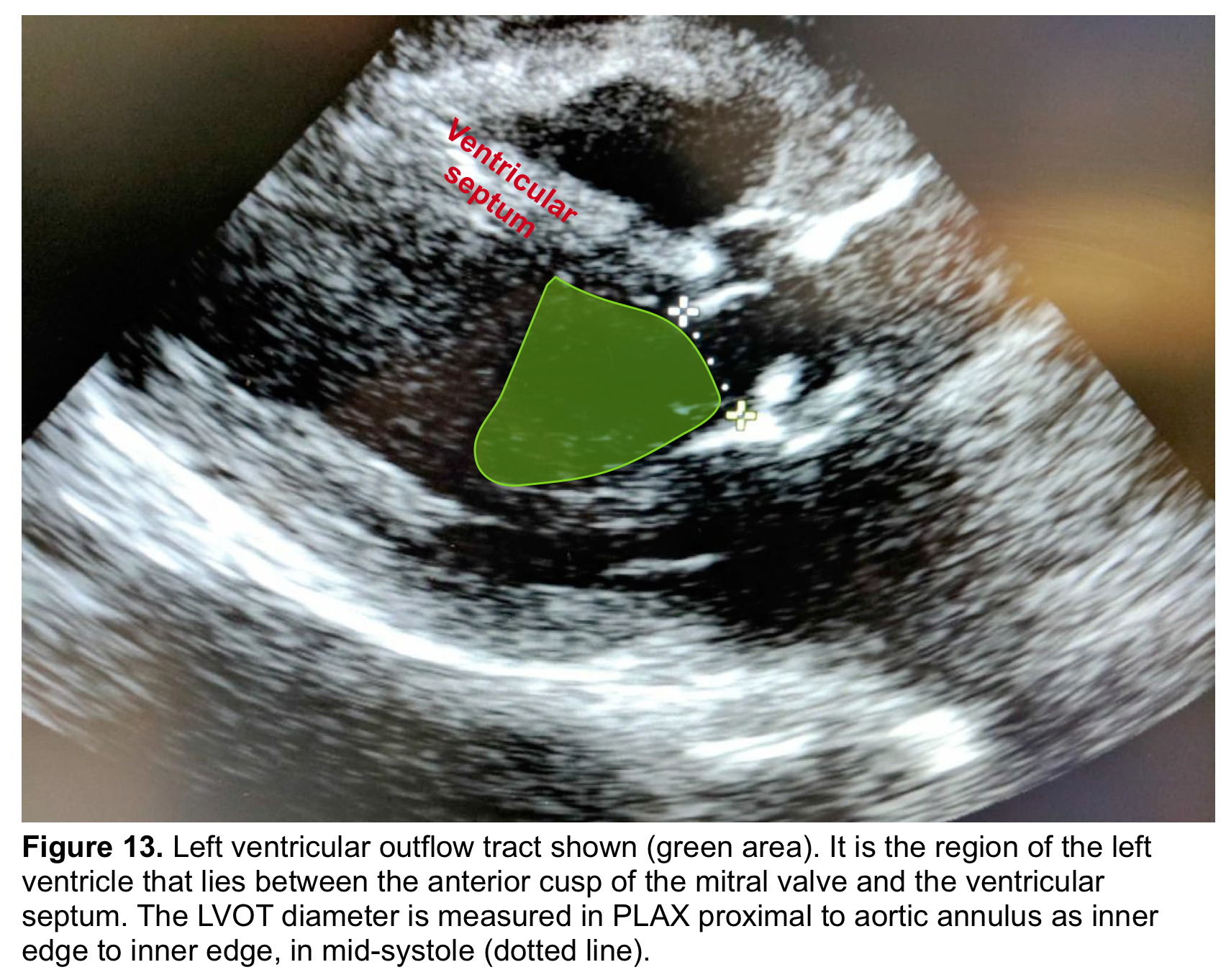

- The ‘LVOT’ is the region of the LV that lies between the anterior cups of the mitral valve and the ventricular septum (figure 13) *.

- From the PLAX view, the width of the AR jet can be measured (figure 14). This dimension is then divided to LVOT diameter to express the jet size as a percentage (relative size of the AR jet that occupies the LVOT) *.

- Mild AR: A ratio <25%

- Moderate AR: Ration of 25%-64%

- Severe AR: A ratio of ≧65%

- Mild AR: A ratio <25%

- Advantages: Simple and rapid screen for detection of AR

- Limitation:

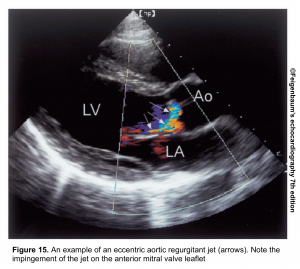

- Mostly applicable to central jets. It may overestimate AR in central jets as AR jets may expand unpredictably below the orifice.

- In an eccentric jet (figure 15), it underestimates the AR.

- Vena contracta (VC)

- VC is the narrowest area of the jet

- Best visualized in zoomed, PLAX view.

- The severity of AR is suggested by VC as

- Mild AR: A VC of < 0.3 cm

- Moderate AR: VC of 0.3-0.6 cm

- Severe AR: A VC of > 0.6 cm *

- Flow convergence

- It can be used for the evaluation of AR severity similar to MR.

- Zooming on the LVOT in the PLAX views is the best approach to record the proximal flow convergence area *.

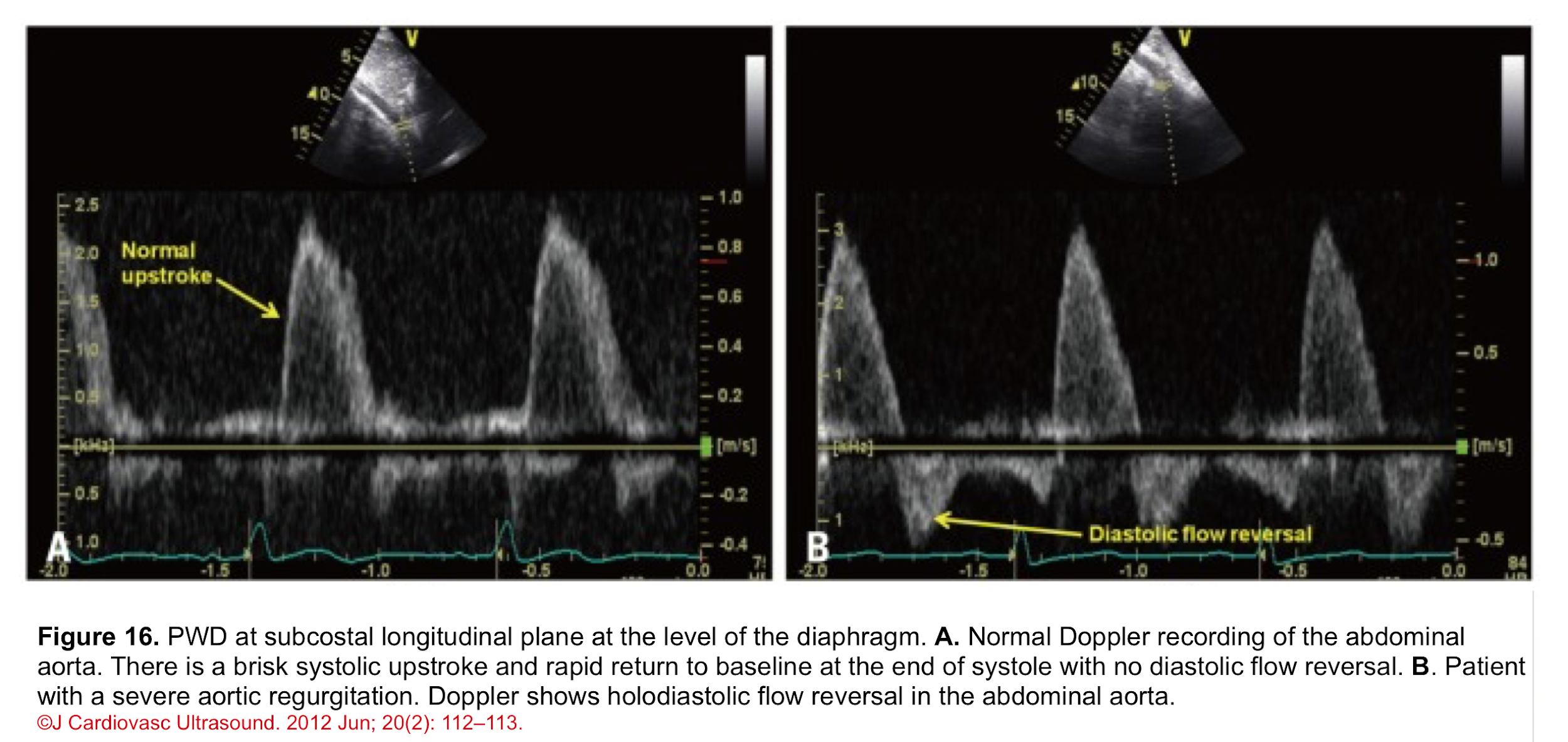

Pulse Wave Doppler (PWD)

- Normal PWD of abdominal aorta: It should show no or just a brief early diastolic flow reversal.

- Holodiastolic flow reversal in the abdominal aorta: It is a supportive finding for severe AR in the presence of other related findings (figure 16) *.

- Differential diagnosis: In the absence of AR, holodiastolic retrograde aortic flow can also be seen in other conditions (e.g. a left-to-right shunt across a patent ductus arteriosus).

Interpretation of echo findings

Clinical question #2: I have performed POCUS on my critically ill patient and other diagnostic possibilities are less likely. AR is on top of my differential diagnosis list. Is this a severe AR?

Since no single measurement or Doppler parameter is precise enough to quantify AR in individual patients, integration of multiple parameters is required as:

In the presence of ≧4 following strong parameters, AR is defined as severe and no further sophisticated and time-consuming quantitative assessment is warranted *.😀

- 2D echo:

- Flail valve, large coaptation defect. (Flail cups defined as the complete eversion of a cusp into the LVOT in long-axis views)

- LV dilatation, particularly with preserved LV function, is a supportive sign of significant AR and becomes more specific with the exclusion of other causes of LV volume overload (e.g. ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy).

- CFD: the presence of the following findings is specific for a severe AR:

- Central jet width ≧65% of LVOT, or eccentric jet hugging the wall of LVOT

- Large flow convergence

- Vena contracta width >0.6 cm

- PWD: Prominent holodiastolic flow reversal in the abdominal aorta (with end-diastolic velocity > 20cm/s)

In the presence of ≧4 following strong parameters, AR is defined as mild, and no further sophisticated and time-consuming quantitative assessment is warranted *😀

- 2D: Normal aortic leaflets, normal LV size

- CFD:

- Jet size: small (<25%) in central jet

- Flow convergence: None or very small

- VCW: <0.3cm

- PWD: Absent or a brief early diastolic reversal in the abdominal aorta

👉If 2-3 criteria for either mild or severe MR were met, then it’s “probably” moderate, and further quantitative assessment is required which is beyond the scope of our discussion *.

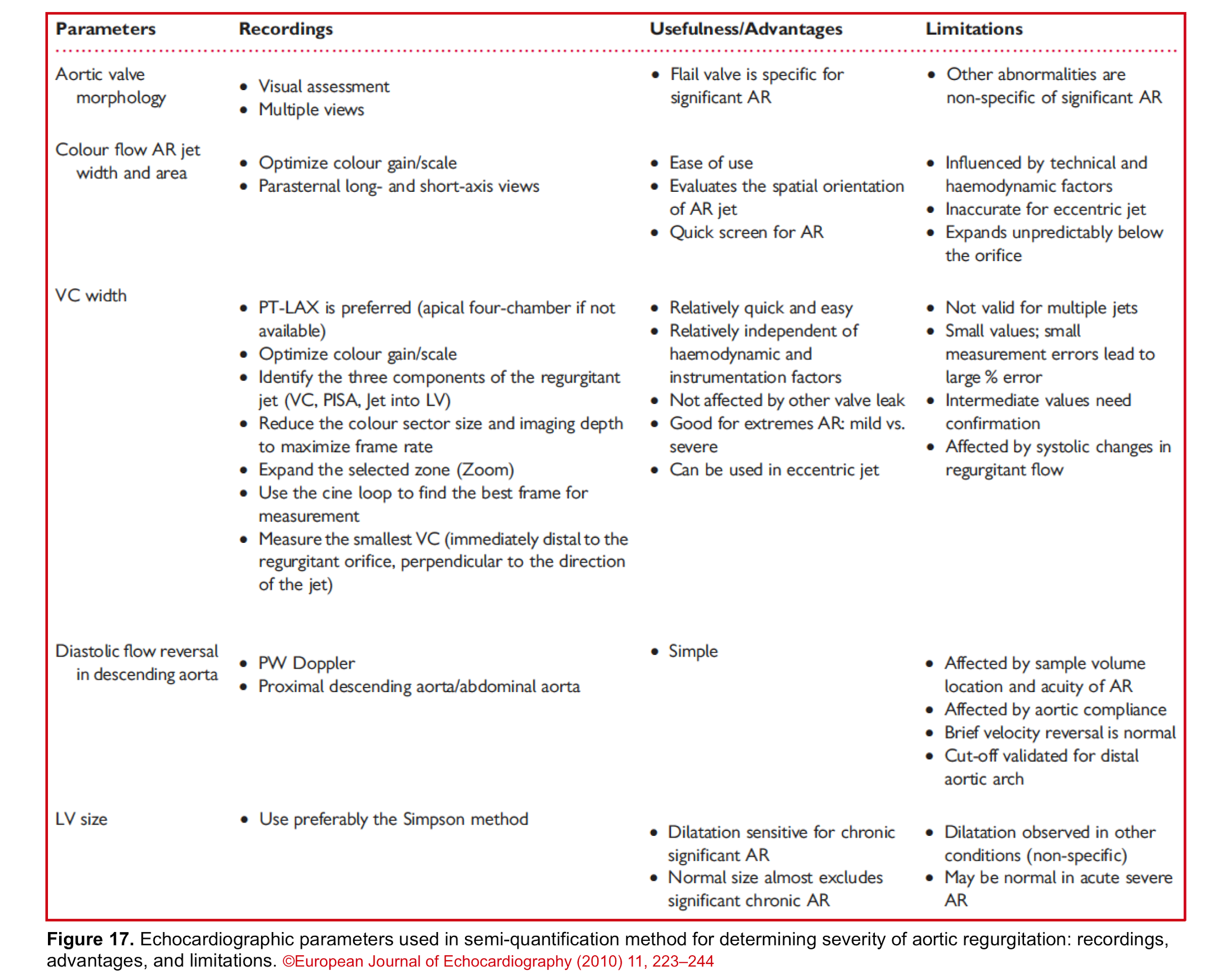

Bottom line: Since each echocardiographic parameter has its own advantages and limitations, try to evaluate and determine the severity of AR by multiple methods. The following table (figure 17) summarizes the usefulness and limitations of each method.

Management: General Strategy in ED

Clinical question #3: How has my management plan been changed by identifying a severe AR?

Patients with acute severe AR (and decompensated chronic MR) are critically ill with significant abnormalities that require emergent surgical treatment. Meanwhile, temporary stabilization is attempted under close monitoring in the intensive care unit. The principles of stabilization of patients with acute severe AR is relatively similar to patients with acute severe MR (more on this here) and involve *, *, *:

- Improving oxygenation with BiPAP and in extreme cases possibly intubation

- Hemodynamic support in patients with low MAP and signs of poor organ perfusion with low dose epinephrine (e.g. <8mcg/min), or possibly dobutamine

- Aggressive approach to terminate significant dysrhythmias

While intra-aortic balloon pumps in patients with acute severe MR may be considered as a temporizing measure; in acute severe AR it is contraindicated as the inflation of the balloon worsens the regurgitant flow across the aortic valve during diastole and precipitates worsening of forward flow *.

🔴The general management strategy in valvular emergencies is summarized below.

- Patients with critical valvular disease usually fail to respond to medical therapy alone *.

- The goal of medical therapy and mechanical circulatory support (MCS) is stabilization prior to definitive correction of the lesion.

- Generally, patients with regurgitant lesions require aggressive afterload reduction and inotropic support *, while those with stenotic lesions may paradoxically require β-blockade and vasoconstrictors (table below) *.

Special conditions

- Aortic Dissection

- The only effective treatment for patients with aortic dissection and concomitant acute severe AR is emergency surgery. Interim medical treatment is guided by clinical presentation, especially systolic blood pressure. If the patient is hypertensive vasodilator therapy with cautious use of beta blockers may be considered. Although standard recommendations for beta-blocker therapy patients with aortic dissection suggest a target heart rate <60 BPM prior to initiation of vasodilator therapy, in patients with concomitant acute severe AR, such heart rate lowering may not be tolerated; and a higher target may be more appropriate.

- 👉Patients with aortic dissection and severe AR are not well tolerable to beta-blockers since it blocks the compensatory tachycardia and may cause profound hypotension *.

- Endocarditis

- Start broad-spectrum antibiotic (class I recommendation) and involve cardiothoracic surgery *.

Multiple and Mixed Valvular Heart Disease

- Multiple VHD refers to the combination of stenotic or regurgitant lesions occurring on ≥2 cardiac valves.

- Mixed VHD refers to the combination of stenotic and regurgitant lesions on the same valve *.

- The hemodynamic and clinical consequences of any given valvular lesion may be modulated by the concomitant presence of mixed or multiple VHD. These hemodynamic interactions can promote, exacerbate, or, in contrast, blunt the clinical expression of each singular lesion *.

- Conditions that can reduce the effective LV forward flow in patients with AR:

- Increasing LV volume loading

- Concomitant MR

- Bradycardia

- ↑Afterload (e.g. Hypertension, aortic stenosis)

- ↓Inotrope

- Hypotension →↓Coronary perfusion pressure →myocardial ischemia. This can happen through the following mechanisms:

- ↓Diastolic BP

- ↑LVEDP resulting in coronary perfusion pressure (CPP= DBP-LVEDP)

- Hypertrophic myocardium (often in chronic AR).

- Increasing LV volume loading

- In patients with AR, the presence of concomitant MR will worsen the loading condition of LV, while concomitant MS will unload the LV and delay symptoms associated with AR.

- Keep in mind that patients with pre-existing small LV cavities (concentric LVH) have a non-compliant LV and a small preload reserve. These patients are less tolerant to acute severe AR.

- How AR can affect indices of LV systolic function?

- In patients with AR, LVEF overestimates the LV function while the patient could have a picture of heart failure *.

- In the case of AR, the heart pumps blood out of the LV during systole, and then a part of this pumped volume leaks back through the incompetent aortic valve during diastole. When this happens, the net SV across the aortic valve is reduced. LVEF overestimates the systolic function of LV.

- 👉Moreover, in AR, stroke volume measurement by LVOT VTI overestimates the forward flow too, since the regurgitant diastolic flow is not considered *.

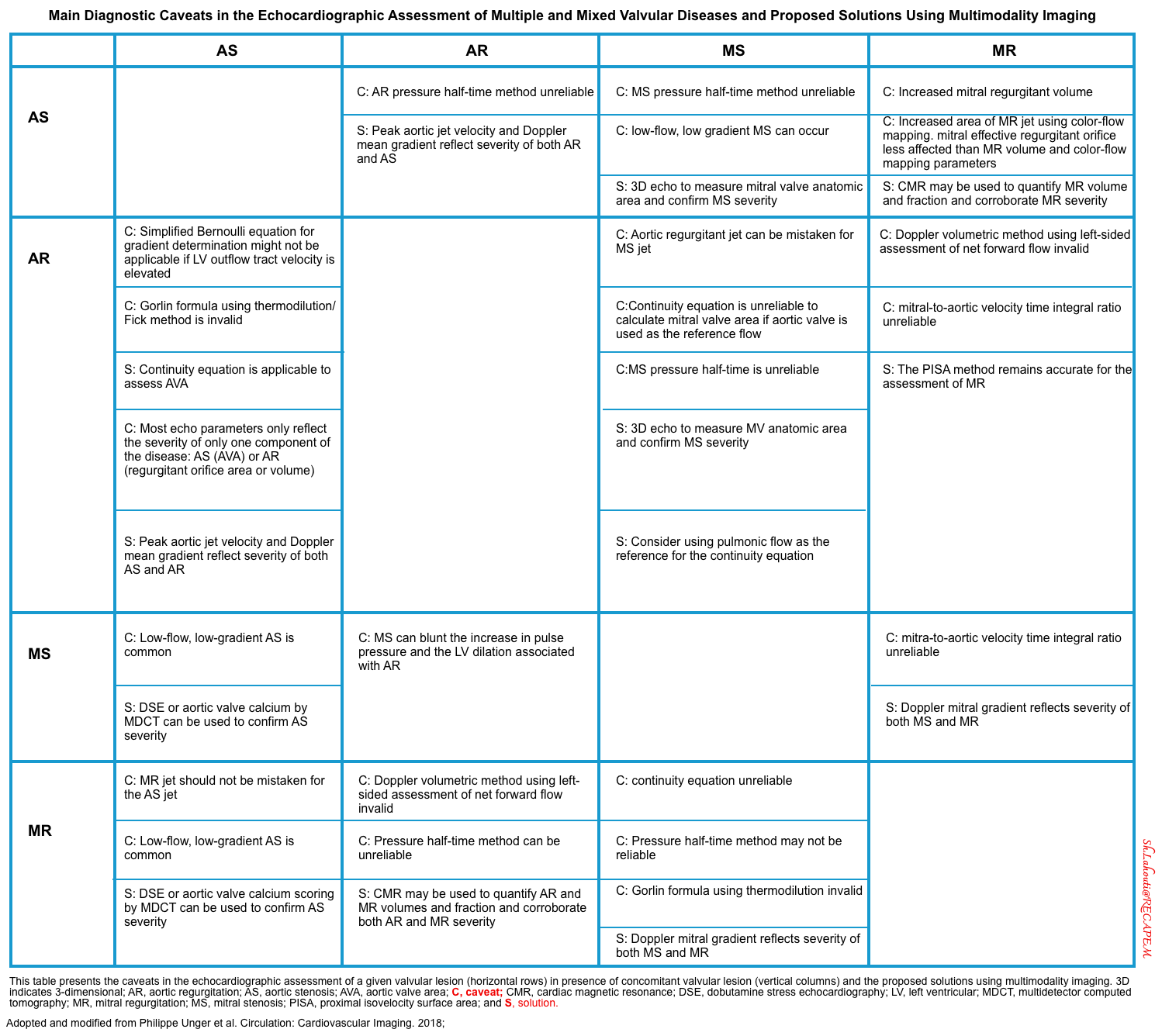

- The main diagnostic caveats in the echocardiographic assessment of multiple and mixed valvular diseases are summarized below.

Going Further

- Ultrasound of cardiac valves (part 1)

- Ultrasound of cardiac valves (part 2)

- Cardiogenic Shock (EM:RAP)

- Resuscitation of CHF with Cardiogenic Shock (EM:RAP)

Post Peer Reviewed by: Reza Moazzeni, M.D. and Mojtaba Chardoli, M.D.

References

1. Charitos EI, Sievers HH. Anatomy of the aortic root: implications for valve-sparing surgery. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;2(1):53-56. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2225-319X.2012.11.18

2. Siu SC, Silversides CK. Bicuspid aortic valve disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010 Jun 22;55(25):2789-800. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.12.068. PMID: 20579534

3. Sievers HH, Schmidtke C. A classification system for the bicuspid aortic valve from 304 surgical specimens. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007 May;133(5):1226-33. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.01.039. PMID: 17467434

4. Sievers HH, Hemmer W, Beyersdorf F, Moritz A, Moosdorf R, Lichtenberg A, Misfeld M, Charitos EI; Working Group for Aortic Valve Surgery of German Society of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. The everyday used nomenclature of the aortic root components: the tower of Babel? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012 Mar;41(3):478-82. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezr093. Epub 2011 Dec 1. PMID: 22345173.

5. Walmsley R. Anatomy of left ventricular outflow tract. Br Heart J. 1979;41(3):263-267. doi:10.1136/hrt.41.3.263

6. Enriquez-Sarano M, Tajik AJ. Clinical practice. Aortic regurgitation. N Engl J Med. 2004 Oct 7;351(15):1539-46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp030912. PMID: 15470217

7. Okafor I, Raghav V, Midha P, Kumar G, Yoganathan A. The hemodynamic effects of acute aortic regurgitation into a stiffened left ventricle resulting from chronic aortic stenosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2016 Jun 1;310(11):H1801-7. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00161.2016. Epub 2016 Apr 22. PMID: 27106040; PMCID: PMC6189743

8.Chasapi A, Mbonye KA, Bajomo O, Young WJ, Primus C, Ambekar S, Wong K, Uppal R, Davies LC, Khanji MY, Woldman S, Lloyd G, Bhattacharyya S. Clinical and echocardiographic predictors of decompensation in acute severe aortic regurgitation due to infective endocarditis. Echocardiography. 2021 Apr;38(4):590-595. doi: 10.1111/echo.15028. Epub 2021 Mar 12. PMID: 33711172.

9. Regeer MV, Versteegh MI, Ajmone Marsan N, Schalij MJ, Klautz RJ, Bax JJ, Delgado V. Left ventricular reverse remodeling after aortic valve surgery for acute versus chronic aortic regurgitation. Echocardiography. 2016 Oct;33(10):1458-1464. doi: 10.1111/echo.13295. Epub 2016 Jun 25. PMID: 27343211

10. Carabello BA. Progress in mitral and aortic regurgitation. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2001 May-Jun;43(6):457-75. doi: 10.1053/pcad.2001.24597. PMID: 11431801

11. Zoghbi WA, Adams D, Bonow RO, Enriquez-Sarano M, Foster E, Grayburn PA, Hahn RT, Han Y, Hung J, Lang RM, Little SH, Shah DJ, Shernan S, Thavendiranathan P, Thomas JD, Weissman NJ. Recommendations for Noninvasive Evaluation of Native Valvular Regurgitation: A Report from the American Society of Echocardiography Developed in Collaboration with the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2017 Apr;30(4):303-371. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2017.01.007. Epub 2017 Mar 14. PMID: 28314623

12. Lancellotti P, Tribouilloy C, Hagendorff A, Popescu BA, Edvardsen T, Pierard LA, Badano L, Zamorano JL; Scientific Document Committee of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Recommendations for the echocardiographic assessment of native valvular regurgitation: an executive summary from the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013 Jul;14(7):611-44. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jet105. Epub 2013 Jun 3. PMID: 23733442

13. Lancellotti P, Tribouilloy C, Hagendorff A, Moura L, Popescu BA, Agricola E, Monin JL, Pierard LA, Badano L, Zamorano JL; European Association of Echocardiography. European Association of Echocardiography recommendations for the assessment of valvular regurgitation. Part 1: aortic and pulmonary regurgitation (native valve disease). Eur J Echocardiogr. 2010 Apr;11(3):223-44. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jeq030. PMID: 20375260

14. Stout KK, Verrier ED. Acute valvular regurgitation. Circulation. 2009 Jun 30;119(25):3232-41. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.782292. PMID: 19564568

15. Goldstein, S. A., Evangelista, A., Abbara, S., Arai, A., Asch, F. M., Badano, L. P., Bolen, M. A., Connolly, H. M., Cuéllar-Calàbria, H., Czerny, M., Devereux, R. B., Erbel, R. A., Fattori, R., Isselbacher, E. M., Lindsay, J. M., McCulloch, M., Michelena, H. I., Nienaber, C. A., Oh, J. K., … Schepens, M. (2015). Multimodality imaging of diseases of the thoracic aorta in adults: From the American society of echocardiography and the european association of cardiovascular imaging: Endorsed by the society of cardiovascular computed tomography and society for cardiova. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography, 28(2), 119–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.echo.2014.11.015

16. Thiele H, Ohman EM, Desch S, Eitel I, de Waha S. Management of cardiogenic shock. Eur Heart J. 2015 May 21;36(20):1223-30. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv051. Epub 2015 Mar 1. PMID: 25732762

17. van Diepen S, Katz JN, Albert NM, Henry TD, Jacobs AK, Kapur NK, Kilic A, Menon V, Ohman EM, Sweitzer NK, Thiele H, Washam JB, Cohen MG; American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research; and Mission: Lifeline. Contemporary Management of Cardiogenic Shock: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017 Oct 17;136(16):e232-e268. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000525. Epub 2017 Sep 18. PMID: 28923988

18. Baran DA, Grines CL, Bailey S, Burkhoff D, Hall SA, Henry TD, Hollenberg SM, Kapur NK, O’Neill W, Ornato JP, Stelling K, Thiele H, van Diepen S, Naidu SS. SCAI clinical expert consensus statement on the classification of cardiogenic shock: This document was endorsed by the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American Heart Association (AHA), the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM), and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) in April 2019. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2019 Jul 1;94(1):29-37. doi: 10.1002/ccd.28329. Epub 2019 May 19. PMID: 31104355.

19. Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP 3rd, Guyton RA, O’Gara PT, Ruiz CE, Skubas NJ, Sorajja P, Sundt TM 3rd, Thomas JD; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 Jun 10;63(22):e57-185. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.02.536. Epub 2014 Mar 3. Erratum in: J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 Jun 10;63(22):2489. Dosage error in article text. PMID: 24603191

20. Hiratzka LF, Bakris GL, Beckman JA, Bersin RM, Carr VF, Casey DE Jr, Eagle KA, Hermann LK, Isselbacher EM, Kazerooni EA, Kouchoukos NT, Lytle BW, Milewicz DM, Reich DL, Sen S, Shinn JA, Svensson LG, Williams DM; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; American Association for Thoracic Surgery; American College of Radiology; American Stroke Association; Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; Society of Interventional Radiology; Society of Thoracic Surgeons; Society for Vascular Medicine. 2010 ACCF/AHA/AATS/ACR/ASA/SCA/SCAI/SIR/STS/SVM guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with Thoracic Aortic Disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American College of Radiology, American Stroke Association, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and Society for Vascular Medicine. Circulation. 2010 Apr 6;121(13):e266-369. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181d4739e. Epub 2010 Mar 16. Erratum in: Circulation. 2010 Jul 27;122(4):e410. PMID: 20233780.

21. Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, Bongiorni MG, Casalta JP, Del Zotti F, Dulgheru R, El Khoury G, Erba PA, Iung B, Miro JM, Mulder BJ, Plonska-Gosciniak E, Price S, Roos-Hesselink J, Snygg-Martin U, Thuny F, Tornos Mas P, Vilacosta I, Zamorano JL; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: The Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 21;36(44):3075-3128. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv319. Epub 2015 Aug 29. PMID: 26320109.

22. Akodad M, Schurtz G, Adda J, Leclercq F, Roubille F. Management of valvulopathies with acute severe heart failure and cardiogenic shock. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2019 Dec;112(12):773-780. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2019.06.009. Epub 2019 Sep 3. PMID: 31492536

23. Bernard S, Deferm S, Bertrand PB. Acute valvular emergencies. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2022 Aug 9;11(8):653-665. doi: 10.1093/ehjacc/zuac086. PMID: 35912478

24. Jentzer JC, Ternus B, Eleid M, Rihal C. Structural Heart Disease Emergencies. J Intensive Care Med. 2021 Sep;36(9):975-988. doi: 10.1177/0885066620918776. Epub 2020 Apr 21. PMID: 32314662.

25. Unger P, Pibarot P, Tribouilloy C, Lancellotti P, Maisano F, Iung B, Piérard L; European Society of Cardiology Council on Valvular Heart Disease. Multiple and Mixed Valvular Heart Diseases. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018 Aug;11(8):e007862. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.118.007862. PMID: 30354497.

26. Unger P, Clavel MA, Lindman BR, Mathieu P, Pibarot P. Pathophysiology and management of multivalvular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2016 Jul;13(7):429-40. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2016.57. Epub 2016 Apr 28. PMID: 27121305; PMCID: PMC5129845

27. Yousef, H.A., Hamdan, A.E.S., Elminshawy, A. et al. Corrected calculation of the overestimated ejection fraction in valvular heart disease by phase-contrast cardiac magnetic resonance imaging for better prediction of patient morbidity. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med 51, 11 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43055-019-0130-8

28. Soliman-Aboumarie, H., Pastore, M. C., Galiatsou, E., Gargani, L., Pugliese, N. R., Mandoli, G. E., Valente, S., Hurtado-Doce, A., Lees, N., & Cameli, M. (2022). Echocardiography in the intensive care unit: An essential tool for diagnosis, monitoring and guiding clinical decision-making. Physiology International, 14(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1556/1647.2021.00055

Add comment