19, June, 2022 by Shahriar Lahouti.

CONTENTS

- Preface

- Etiology

- Pathogenesis

- Evaluation

- General approach

- Management of uncomplicated ascites

- Complicated ascites

- Going further

- Appendix

- Media

- References

Preface

Pathologic accumulation of fluid within peritoneal cavity results in ascites. Ascites is commonly due to portal hypertension resulting from cirrhosis. Most often bacterial infection (especially spontaneous bacterial peritonitis) is the primary cause for decompensation in patients with cirrhosis. Here, the evaluation, diagnosis and management of ascites and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis will be reviewed.

Etiology of ascites

- Hepatic source

- Cirrhosis (~80%) *

- Acute liver failure

- Alcoholic Hepatitis

- Hepatic vein thrombosis (Budd-Chiari Syndrome)

- Extra-hepatic source

- Heart Failure (3%). It is usually associated with pulmonary hypertension.

- Malignancy-related ascites (10%)

- Peritoneal carcinomatosis

- Massive liver metastasis (causing portal hypertension)

- Other

- Peritoneal disease e.g. peritoneal dialysis, peritoneal infection (e.g. peritoneal tuberculosis), peritoneal carcinomatosis, ventriculoperitoneal shunt.

- OB/GYN: Endometriosis, abdominal pregnancy, ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome

- Portal vein thrombosis

- Nephrotic Syndrome

- Bowel perforation

- Pancreatitis

- Myxedema

- Hemodialysis-associated ascites

- Mixed (5%)

- Ascites that results from combination of 2 or more causes, e.g. cirrhosis plus 1 other cause such as peritoneal carcinomatosis.

- Many patients with inexplicable ascites are finally found to have 2 or even 3 causes for ascites formation (e.g. heart failure, diabetic nephropathy, and cirrhosis due to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis). In this setting, the aggregate of predisposing factors can lead to sodium and water retention when every individual factor might not be severe enough to cause surplus fluid.

- Ascites that results from combination of 2 or more causes, e.g. cirrhosis plus 1 other cause such as peritoneal carcinomatosis.

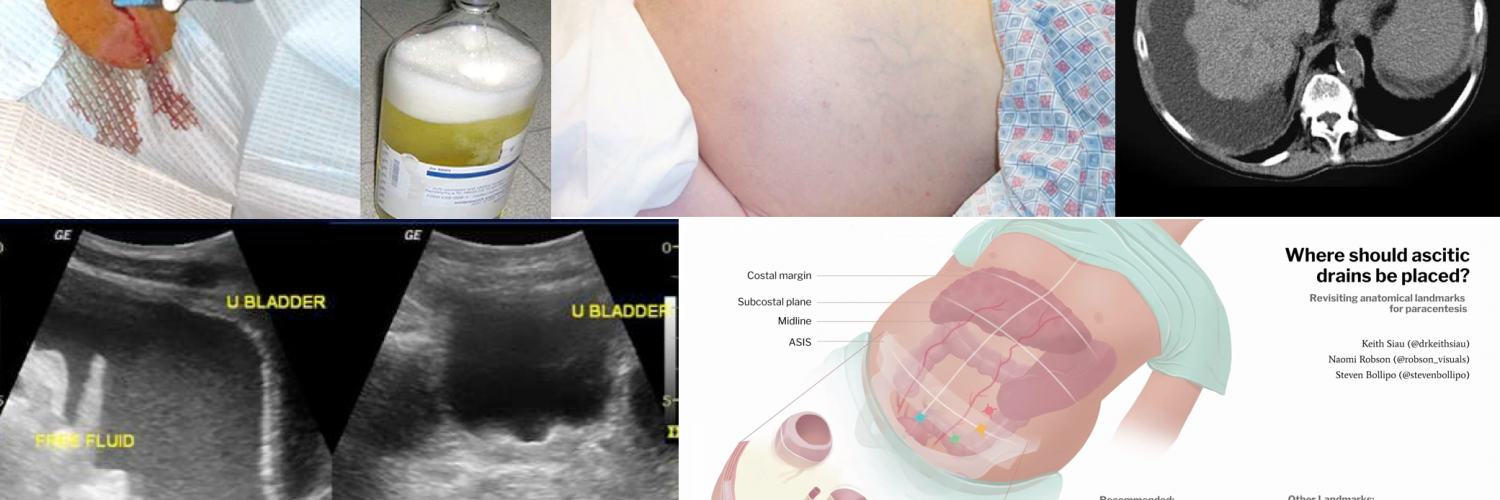

Pathogenesis

In cirrhosis, ascites results from portal hypertension (PHT), modifications in vascular tone and renal sodium retention *. The pathogenesis of ascites and related complications are summarized in the following figure. The key pathogenetic events include:

- Portal hypertension. The development of PHT is the first step toward sodium retention in the context of cirrhosis. Patients with cirrhosis but without PHT do not develop ascites or edema.

- It has been shown that a portal pressure of ≧12 mmHg is probably required for fluid retention *,*. It appears that sinusoidal hypertension is required for fluid retention. Presinusoidal portal hypertension (e.g. in portal vein thrombosis) does not result in ascites formation in the absence of other contributing factors.

- Modification in vascular tone. Increased portal pressure signals to the splanchnic system to promote vasodilation and increase portal flow. Nitric oxide is a major player in mediating splanchnic vasodilation. Splanchnic vasodilation leads to shunting of cardiac output from the systemic circulation to the mesentery, resulting to systemic hypotension and relative renal hypoperfusion.

- Renal sodium retention. Relative arterial underfilling and systemic hypotension promotes activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS). Angiotensin system leads to sodium (Na) and fluid retention, causing systemic volume overload.

Evaluation

History

- Ascites represents a very common manifestation of decompensated cirrhosis and thus on presentation if cirrhosis has not already been defined for the patient, risk factors for its usual precursors, namely alcoholic use, viral hepatitis and NASH should be explored.

- Assess for risk factors associated with extra-hepatic causes of ascites; e.g. heart disease, hematologic disorder (thrombosis, excessive bleeding), malignancy and risk factors for tuberculous.

- Medications review (hepatotoxins).

Signs and symptoms

- Painless abdominal distention.

- Signs & symptoms associated with hepatic decompensation e.g. confusion or evidence of gastrointestinal bleeding, jaundice.

- Signs of chronic liver disease: spider angioma, palmar erythema, and abdominal wall collaterals.

- Patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis may presents with fever +/- abdominal pain (see below).

- Dyspnea (due to fluid accumulation and mechanical effect on diaphragm or secondary to presence of hydrothorax).

Course

- The time course over which the distension develops depends on the etiology of the ascites as:

- Sudden onset (over days) may be seen with acute liver failure, hepatic or portal vein thrombosis, compression of the IVC due to trauma with a hematoma or infection.

- Gradual development over weeks can suggest classical liver disease or alcoholic hepatitis.

- Slow development over months may be suggestive for malignant ascites.

Physical exam

- Flank dullness, shifting dullness.

- Frank peritoneal signs on exam or localizing abdominal pain is usually absent in cirrhotic ascites and “SBP”.

- Presence of localizing tenderness should suggest secondary bacterial peritonitis, portal vein thrombosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

- If pleural effusions (hydrothorax) are present, the right effusion is usually greater than the left.

- Ascites as the result of heart failure presents with jugular venous distension, pulmonary congestion, or peripheral edema.

Diagnosis

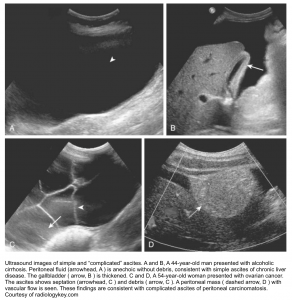

- The diagnosis of ascites is established with a combination of physical examination and abdominal imaging (usually ultrasonography).

- A grading system has been proposed by the International Ascites Club:

- Grade 1: Mild ascites detectable only by ultrasound examination.

- Grade 2: Moderate ascites manifested by moderate symmetrical distension of the abdomen

- Grade 3: Large or gross ascites with marked abdominal distension *.

- An older system that grades ascites from 1+ to 4+ is also used. In this system 1+ is minimal and barely detectable, 2+ is moderate, 3+ is massive but not tense, and 4+ is massive and tense.

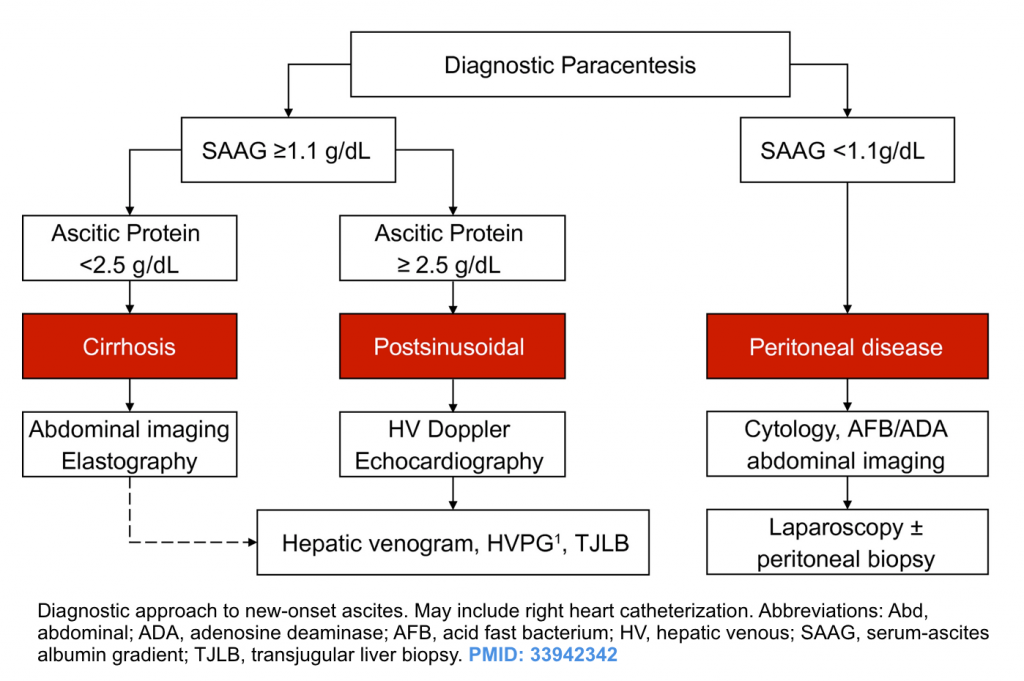

Determining the cause of ascites. Once the diagnosis of ascites is made, the next step is to look for the cause of liver disease and ascites formation. Patients who have a cause for ascites formation other than cirrhosis ( e.g. peritoneal carcinomatosis, hepatic vein thrombosis) may not respond to the treatments used in those with cirrhosis (i.e. sodium restriction and diuretics). The diagnostic approach to new onset ascites is shown below.

- Liver disease lab panel (appendix)

- Diagnostic paracentesis typically to characterize the fluid origin, and whether it is sterile, infectious and/or malignant.

- Indications *

- Any new onset of ascites.

- Testing of ascitic fluid in a patient with preexisting ascites who is admitted to the hospital, regardless of the reason for admission.

- Any patient with cirrhosis and ascites who has signs of clinical deterioration e.g. GI bleeding (is a high risk time for infection), fever, abdominal pain/tenderness, hepatic encephalopathy, hypotension, peripheral leukocytosis, worsening renal function, or metabolic acidosis.

- Clinical suspicion for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

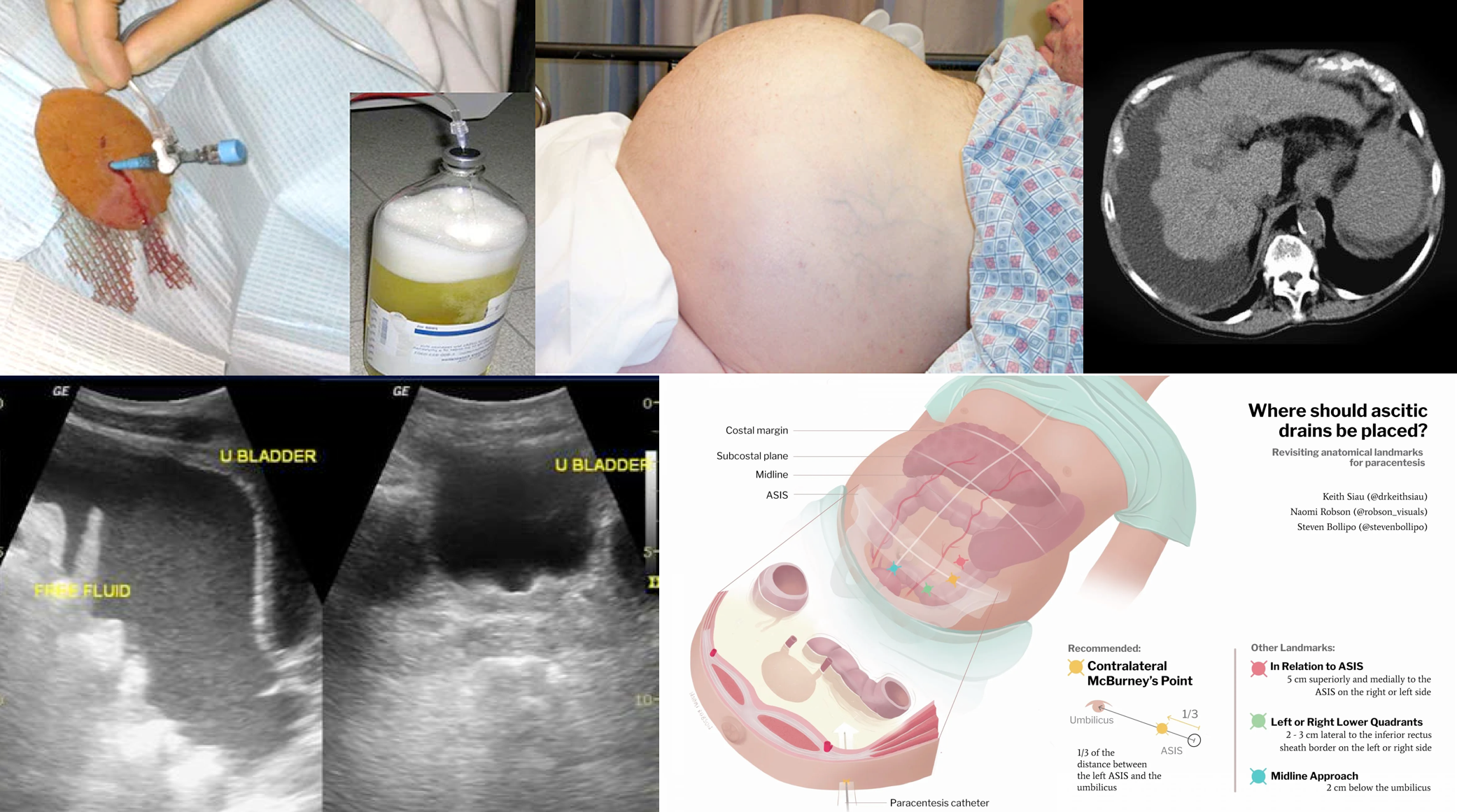

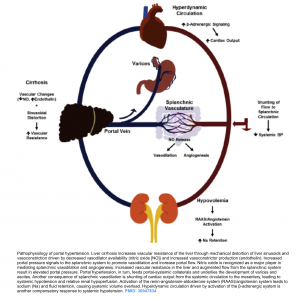

- Tips on diagnostic paracentesis

- Paracentesis is a relatively safe procedure with <1% chance of adverse event or complication *.

- Perform paracentesis under ultrasound guide to minimize the risk of complications especially in patients with a massive ileus with bowel distension.

- An elevated INR or thrombocytopenia is not a contraindication to paracentesis, and in most patients there is no need to transfuse fresh frozen plasma or platelets prior to the procedure *.

- The only exceptions are clinically apparent DIC or clinically apparent hyperfibrinolysis; for which coagulation abnormality should be corrected before performing the procedure *.

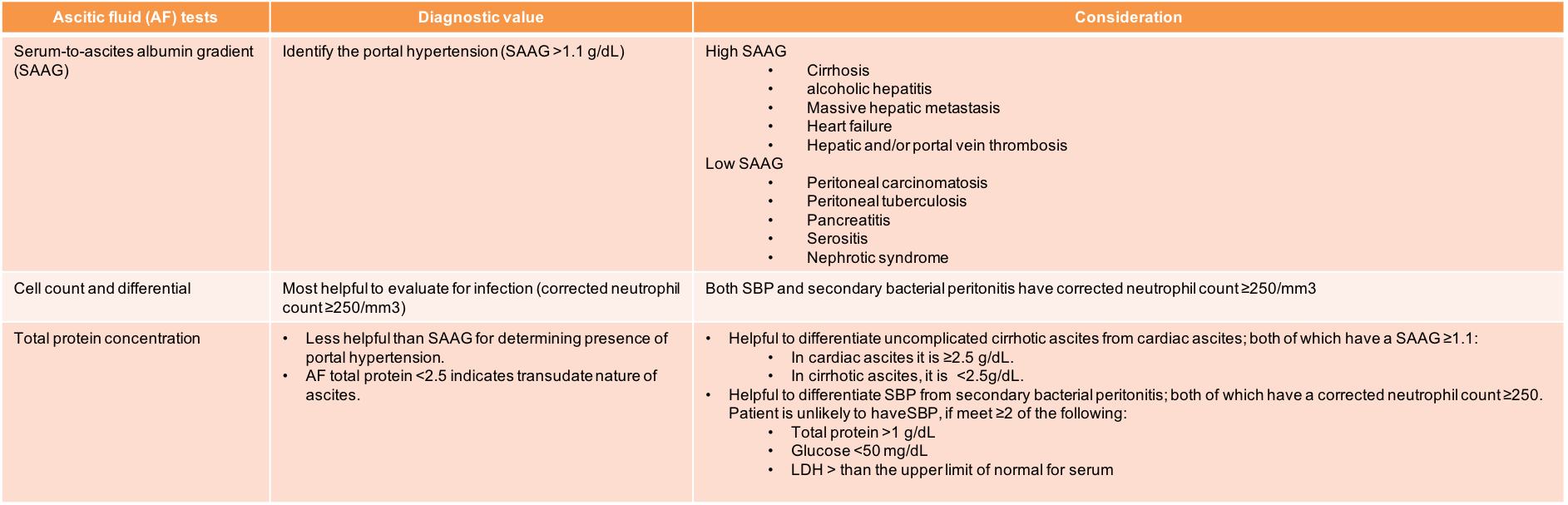

- General evaluation of ascitis fluid (see interpretation in table below)

- Cell counts and differential.

- Total protein, albumin.

- When there’s concern for SBP, also test for Gram stain, glucose, LDH, and bacterial cultures (Ideally, culture bottles should be inoculated at the bedside: 10 ml each into an anaerobic bottle and an aerobic bottle.)

- Additional tests may be indicated based on the clinical setting and results of initial testing. These may include:

- Amylase concentration (pancreatic ascites or bowel perforation)

- Tuberculosis smear, culture, and adenosine deaminase activity (tuberculous peritonitis)

- Cytology and possibly carcinoembryonic antigen level (malignancy)

- Triglyceride concentration (chylous ascites)

- Bilirubin concentration (bowel or biliary perforation)

- Indications *

Abdominal imaging

- “Complete abdominal ultrasound” including Doppler study. See media for portal vein Doppler protocol.

- Ultrasound findings in patients with portal hypertension may reveal *

- Dilation of the portal vein to ≥13 mm.

- Dilation of the splenic and superior mesenteric veins to ≥11 mm.

- Reduction in portal venous blood flow velocity (<16 cm/sec).

- Biphasic or reverse flow in portal vein (late stage): pathognomonic.

- Splenomegaly (greatest dimension >12 cm).

- Ultrasound findings in patients with portal hypertension may reveal *

- A triple-phase CT scan may be considered in appropriate context to rule out complications such as hepatocellular carcinoma and portal vein thrombosis.

Diagnostic approach to new onset ascites

Interpretation of ascites fluid tests

General approach

The overview to diagnosis and management of cirrhotic ascites is presented in the following figure.

Management of uncomplicated ascites

Benefit of fluid removal

- Patients feel much better, have less abdominal discomfort and have less shortness of breath *.

- As fluid is removed, ascitic fluid opsonins become more concentrated, which may protect against spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

- Reductions in the risk of variceal hemorrhage *, cellulitis, abdominal wall hernia formation and hepatic hydrothorax.

Rate of fluid removal

- The goals of therapy in patients with ascites are to minimize ascitic fluid volume and decrease peripheral edema, without causing intravascular volume

depletion. The rate at which fluid can safely be removed in cirrhosis depends upon the presence or absence of peripheral edema.- In patients with peripheral edema, fluid mobilization can be rapid (maximum weight loss of 1 Kg per day) without detectable intravascular volume depletion *.

- In patients with ascites without edema, the recommended maximum weight loss is 0.5 kg per day *. More rapid fluid removal with diuretics can lead to plasma volume depletion and azotemia. If more rapid fluid removal is required, an initial large-volume paracentesis (LVP) should be performed.

Fluid removal

- Cirrhotic ascites can be mobilized in approximately 90% of patients.

- The initial step involve dietary sodium restriction to < 2g per day (≤ 90 mmol/d) *.

- Diuretics

- Indications to initiate diuretics

- Clinically apparent (grade 2-3) ascites and

- Absence of frank persistent hepatic encephalopathy, active GI bleeding, AKI; and

- Absence of ascitic complications, such as bacterial peritonitis.

- Regimen: Spironolactone and oral furosemide in a ratio of 100:40 mg per day, with doses titrated upward as needed (up to 400 mg spironolactone and 160 mg furosemide per day). Once ascites has largely resolved, the dose of diuretics should be reduced to the lowest effective dose.

- Considerations:

- Be cautious in small-volume ascites, small patients (weight < 50 Kg) and elderly. Start with lower dose of diuretics e.g. 25-50mg of spironolactone and 20mg of furosemide per day. This can be titrated upward if needed.

- In patients with hypokalemia, start spironolactone monotherapy and only add furosemide once the potassium normalizes and potassium replacement is no longer needed.

- Furosemide should be stopped if severe hypokalemia occurs (<3 mmol/L).

- Anti-mineralocorticoids should be stopped if severe hyperkalemia occurs (>6 mmol/L).

- Indications to initiate diuretics

- Therapeutic paracentesis.

- Indications *

- Tense ascites.

- Tense ascites may increase intra-abdominal pressure and cause a compartment syndrome. Such patients may not respond well to diuresis, due to renal dysfunction as well.

- Massive ascites in the absence of peripheral edema.

- Refractory ascites

- Symptomatic hydrothorax.

- Active variceal bleeding or those at high risk of variceal hemorrhage.

- Exudative ascites or those disorders that are not responsive to diuretic treatment e.g. peritoneal carcinomatosis, hepatic vein thrombosis.

- Tense ascites.

- Large-volume paracentesis (LVP)

- If the patient has tense ascites or if the patient or the clinician is in a hurry to decompress the abdomen, a 5 L paracentesis is more rapid than diuretic therapy. Removal of less than 5 liters of fluid does not appear to have hemodynamic consequences, and post-paracentesis albumin infusion does not appear to be necessary *.

- For LVP, albumin (6 to 8 g per liter of fluid removed) can be administered.

- A meta-analysis demonstrated a survival advantage with albumin infusion after paracentesis involving mean volumes of 5.5 to 15.9 liters.

- Indications *

Medications to avoid or use with caution

- ⚠️Antihypertensive medications *

- In patients with cirrhosis, lowering arterial blood pressure is associated with lower survival rates, so medications that decrease blood pressure ( causing decreased renal perfusion pressure) might decrease survival.

- Avoid ACEIs and/or ARBs in patients with ascites.

- Avoid non-selective beta blockers e.g. propranolol (which is commonly given to prevent variceal hemorrhage in patients with large varices) in patients with refractory ascites.

- In patients with cirrhosis, lowering arterial blood pressure is associated with lower survival rates, so medications that decrease blood pressure ( causing decreased renal perfusion pressure) might decrease survival.

- ⚠️NSAIDs.

- These agents inhibit the synthesis of renal prostaglandins, leading to renal vasoconstriction, a lesser response to diuretics, and the possible precipitation of AKI *. NSAIDs can also precipitate upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the setting of cirrhosis.

- ⚠️Hepatotoxins

Complicated ascites

Ascites is complicated when it is refractory, infected or associated with hepatorenal syndrome *.

Refractory ascites

Refractory ascites is defined as ascites that is not easily mobilized because of ineffectiveness of diuretics and sodium restriction or adverse events from diuretics. This occurs in ~10% of patients with ascites.

- The development of refractory ascites is also associated with further complication of cirrhosis e.g. spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hepatorenal syndrome.

- It carries a poor prognosis with a 1-year median survival of 50%.

Pathogenesis

- Refractory ascites share common pathophysiologic mechanisms with hepatorenal syndrome.

- Marked neurohumoral activation results in renal vasoconstriction and enhanced sodium reabsorption in the proximal tubule (under the influence of angiotensin II and norepinephrine) and collecting tubules (under the influence of aldosterone).

Diagnostic criteria

- Diuretic-resistant ascites in patients with cirrhosis is considered to be present if at least one of the following criteria is fulfilled in the absence of therapy with a NSAID or other nephrotoxic medications.

- An inability to mobilize ascites (manifested by weight loss < 0.8 kg over 4 days) despite confirmed adherence to the dietary sodium restriction and the administration of maximum tolerable doses of oral diuretics (1).

- Reappearance of grade 2 or 3 ascites within 4 weeks of initial mobilization

- The development of diuretic-induced complications such as progressive azotemia, hepatic encephalopathy, or progressive electrolyte imbalances.

(1) Patients must be on intensive diuretic therapy (spironolactone 400 mg/d and furosemide 160 mg/d) for at least 1 week and on a Na-restricted diet of <90 mmol/d.

Differential diagnosis

- Non-adherent to dietary sodium restriction.

- Use of medications that diminish diuretic responsiveness e.g. NSAIDs or other nephrotoxins.

- Malignant ascites due to peritoneal carcinomatosis.

- Note that ascites in massive hepatic metastasis (another cause of malignant ascites) develops due to intrahepatic portal hypertension and is often responsive to diuretic treatment in a similar fashion to patients with cirrhosis.

- Budd-Chiari syndrome (hepatic vein thrombosis).

- Malignant chylous ascites.

Diagnostic evaluation

- Rule out non-adherence to dietary sodium restriction

- Patients who are diuretic-resistant will have inadequate excretion, whereas those who are not adherent to the sodium restriction will gain weight despite what would otherwise be adequate excretion.

- Adherence to the sodium restriction must be confirmed with a 24-hour urine collection (for Na and K excretion) and assessment for weight changes.

- Patients who are diuretic sensitive will excrete ≥78 mEq of sodium per day because of the diuretic with a mean weight loss of >0.8 kg over 4 days.

- Urine sodium excretion ≥78 mEq per day and weight loss: The patient is diuretic sensitive and adherent to the dietary sodium restriction.

- Urine sodium excretion <78 mEq per day and minimal to no weight loss (or weight gain): The patient is diuretic resistant at the current doses.

- Urine sodium excretion ≥78 mEq per day and minimal to no weight loss (or weight gain): The patient is diuretic sensitive but not adherent to the sodium restriction.

- Patients who are diuretic sensitive will excrete ≥78 mEq of sodium per day because of the diuretic with a mean weight loss of >0.8 kg over 4 days.

- Rule out disorders that are typically refractory to diuretic therapy (e.g. to peritoneal carcinomatosis, hepatic vein thrombosis, or malignant chylous ascites).

- Perform diagnostic paracentesis.

- Abdominal ultrasound with Doppler study.

- A triple-phase CT scan to rule out complications such as hepatocellular carcinoma and portal vein thrombosis (either bland clot or metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma).

Management

- Stop medications medications that decrease systemic blood pressure (and thus renal perfusion), such as beta blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), and angiotensin receptor II blockers (ARBs).

- It is particularly important to stop beta blockers since their use has been shown to be associated with increased mortality *.

- Stop nephrotoxins and NSAIDs.

- Continue sodium restriction and diuretics.

- Consider to discontinue diuretics when urinary Na excretion is < 30 mEq/d *.

- Large volume paracentesis followed by albumin administration *.

- Consider transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunt (TIPS) placement in the appropriate patients.

- Liver transplantation.

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

Definition

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) is defined as an ascitic fluid infection without an evident intra-abdominal surgically-treatable source and is commonly a sign of end-stage liver disease. SBP occurs in up to 30% of cirrhotic patients:

- In-hospital mortality of 20%.

- Prevalence of 10% in inpatient cirrhotic patients.

- Prevalence of 3.5% in outpatient cirrhotic patients.

- Asymptomatic. Close to 10% of patients with SBP diagnosed by paracentesis do not display symptoms *,*.

- SBP is present in ~10% of patients admitted to the hospital with cirrhotic ascites, so it should be suspected in any cirrhotic patient who is admitted to the hospital even in the absence of symptoms.

- Fever

- Abdominal pain

- Dysfunction of other organs.

- SBP can trigger failure of other organs and in many cases, these other organ failures are more obvious than SBP itself.

- Hepatic encephalopathy

- Hepatorenal syndrome

- GI bleeding

- Septic shock

- SBP can trigger failure of other organs and in many cases, these other organ failures are more obvious than SBP itself.

- Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF)

- SBP can lead to full-blown acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF), a condition marked by multiple organ failures (e.g. encephalopathy, shock, and renal failure).

Diagnosis

- Each hour of delay in diagnosis (via paracentesis) increases mortality by 3.3% *.

- Diagnosis of SBP is based on diagnostic paracentesis. Perform paracentesis and send ascitic fluid for cell count with differential, Gram stain, culture, glucose, LDH, albumin and total protein.

- It is recommended that at least 20 mL of fluid be placed in 2 blood culture bottles (10 mL each).

- Send blood culture in all patients with suspected SBP before starting antibiotic treatment.

- The diagnosis of SBP is established by an elevated ascitic fluid absolute PMN count (≥250 cells/mm ), and exclusion of secondary causes of bacterial peritonitis.

- Some criteria require the presence of a positive culture. However, approximately 60% of patients will be culture-negative, even with an elevated PMN count *. Antibiotics are still recommended for these patients.

- Ascitic fluid culture positivity is not a prerequisite for the diagnosis of SBP, however culture should be performed in order to guide antibiotic therapy *.

- In some patients at very early stage of SBP, PMN count is < 250 cells/mm3 (bacterascites stage i.e. bacteria are present in the ascitic fluid, but the

PMN count is <250 cells/mm3 *).- Patients with bacterascites who progress to SBP commonly have signs or symptoms of infection (usually fever) at the time of the paracentesis. Treatment should be started for patients with bacterascites who are symptomatic.

- For patients who are asymptomatic, a repeat paracentesis should be obtained after 48 hours (or if the patient develops symptoms) and treatment initiated if the PMN count has risen to ≥250 cells/mm3.

- Some criteria require the presence of a positive culture. However, approximately 60% of patients will be culture-negative, even with an elevated PMN count *. Antibiotics are still recommended for these patients.

Differential diagnosis: 👉Secondary bacterial peritonitis.

- Secondary bacterial peritonitis is a rare complication (<5%) in patients with cirrhotic ascites *. It is associated with the presence of an intra-abdominal sources of infection such as abscess, perforated viscus or inflammation of an intra-abdominal organ (e.g. cholecystitis) in the presence of ascites.

- 🚩Suspect to secondary bacterial peritonitis when any of the following conditions were present *:

- Frank peritoneal signs on exam or localizing abdominal pain.

- Ultrasonography showing complex, loculated fluid (below image c).

- Gram stain or culture of ascitic fluid showing multiple different organisms.

- At least two of the following criteria are present:

-

Ascitic fluid Gram stain has multiple organisms

-

Ascitic fluid LDH is greater than normal serum values

-

Ascitic total protein is >1 g/dL

-

Ascitic glucose is <50 mg/dL

-

- A patient who is treated for “spontaneous bacterial peritonitis” fails to improve.

- Patients with suspected secondary bacterial peritonitis should should undergo prompt abdominopelvic CT scan. They should receive broader spectrum antibiotics (e.g. cefotaxime and metronidazole) and early surgery should be considered.

Treatment

- Antibiotic treatment

- Ideally once paracentesis is completed, antibiotics should be initiated.

- However, if the physician strongly suspects SBP, antibiotics should be provided, no matter the results of ascitic fluid analysis.

- Antibiotic regimen

- For community acquired SBP, a third generation cephalosporin, such as cefotaxime 2g IV q8h or ceftriaxone 2g IV daily, is recommended.

-

Other regimens for penicillin-allergic patients *

-

Ofloxacin 400 mg orally (PO) q12h

-

Levofloxacin 750 mg IV q24h

-

Ciprofloxacin 400 mg IV q12h

-

-

- For suspected nosocomial SBP, a broader coverage is more appropriate (e.g. piperacillin-tazobactam or a carbapenem) *.

- For community acquired SBP, a third generation cephalosporin, such as cefotaxime 2g IV q8h or ceftriaxone 2g IV daily, is recommended.

- Duration of therapy. A short-courses of treatment (five-day) for SBP are effective. Only patients who grow an unusual organism (eg, pseudomonas,

Enterobacteriaceae), an organism resistant to standard antibiotic therapy, or an organism routinely associated with endocarditis (eg, Staphylococcus aureus or viridians group streptococci) are initially considered for longer treatment.

- Prevent development of HRS and decompensated cirrhosis

- SBP may trigger full-blown decompensated cirrhosis, marked by hypotension, malperfusion, and hepatorenal syndrome. The following strategies should be implemented preemptively, to avoid this.

- Albumin 1.5 g/kg IV, followed by a second dose of 1 g/kg on day 3, reduces in-hospital mortality when used with cefotaxime by 19%. Albumin should be considered for patients with:

- Serum creatinine ≥1 mg/dL.

- BUN blood ≥30 mg/dL

- Total bilirubin ≥4 mg/dL.

- Discontinue medications that may reduce renal perfusion e.g. beta blockers, antihypertensive medications such as ACEIs, ARBs.

- Discontinue nephrotoxins e.g. NSAIDs.

Prevention

- General measures

- Diuretic therapy. Diuresis concentrates ascitic fluid, thereby raising ascitic fluid opsonic activity, which may help prevent SBP *.

- Early recognition and aggressive treatment of localized infections (eg, cystitis and cellulitis). This can help to prevent bacteremia and SBP.

- Restricting use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).

- Prophylactic antibiotic

- Antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent SBP is recommended for patients at high risk of developing SBP and is associated with a decreased risk of bacterial infection and mortality.

- Indications and appropriate regimens are:

- Patients with cirrhosis and gastrointestinal bleeding.

- A seven-day course of antibiotic is recommended.

- Ceftriaxone 1g IV per day. Can switch to oral antibiotics once bleeding is stopped and patient is able to eat. Oral regimen include, ciprofloxacin 500 mg BD OR trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) one double-strength BD, OR norfloxacin 400mg BD.

- Patients who have had one or more episodes of SBP.

- Long term daily prophylaxis with any of the following regimen trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (one double-strength daily) OR ciprofloxacin 500 mg/d OR norfloxacin 400mg/d.

- Patients with cirrhosis and ascites if the ascitic fluid protein is <1.5 g/dL along with either impaired renal function (a creatinine ≥1.2 mg/dL, a BUN level ≥25 mg/dL or a serum Na ≤130 mEq/L) or liver failure (a Child-Pugh score ≥9 and a bilirubin ≥3 mg/dL).

- Long-term use of norfloxacin 400mg/d, OR TMP-SMX one double-strength per day.

- Patients with cirrhosis and gastrointestinal bleeding.

Going further

- Sonographic Features of Ascites PoCUS

- Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (IBCC)

- Liver emergencies (emergency medicine cases)

Appendix

Media

References

1. PMID: 8277955. Runyon BA. Care of patients with ascites. N Engl J Med. 1994 Feb 3;330(5):337-42. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199402033300508.

2. PMID: 30947834. Simonetto DA, Liu M, Kamath PS. Portal Hypertension and Related Complications: Diagnosis and Management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019 Apr;94(4):714-726. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.12.020.

3. PMID: 9308123. Ginès P, Fernández-Esparrach G, Arroyo V, Rodés J. Pathogenesis of ascites in cirrhosis. Semin Liver Dis. 1997;17(3):175-89. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007196.

4. PMID: 1484164. Morali GA, Sniderman KW, Deitel KM, Tobe S, Witt-Sullivan H, Simon M, Heathcote J, Blendis LM. Is sinusoidal portal hypertension a necessary factor for the development of hepatic ascites? J Hepatol. 1992 Sep;16(1-2):249-50. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(05)80128-x.

5. PMID: 29653741. European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address: easloffice@easloffice.eu; European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2018 Aug;69(2):406-460. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.024. Epub 2018 Apr 10. Erratum in: J Hepatol. 2018 Nov;69(5):1207.

6. PMID: 29290508. Long B, Koyfman A. The emergency medicine evaluation and management of the patient with cirrhosis. Am J Emerg Med. 2018 Apr;36(4):689-698. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.12.047. Epub 2017 Dec 23.

7. PMID: 29290508. Long B, Koyfman A. The emergency medicine evaluation and management of the patient with cirrhosis. Am J Emerg Med. 2018 Apr;36(4):689-698. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.12.047. Epub 2017 Dec 23.

8. PMID: 15368454. Grabau CM, Crago SF, Hoff LK, Simon JA, Melton CA, Ott BJ, Kamath PS. Performance standards for therapeutic abdominal paracentesis. Hepatology. 2004 Aug;40(2):484-8. doi: 10.1002/hep.20317.

9. PMID: 22045398. Berzigotti A, Ashkenazi E, Reverter E, Abraldes JG, Bosch J. Non-invasive diagnostic and prognostic evaluation of liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Dis Markers. 2011;31(3):129-38. doi: 10.3233/DMA-2011-0835.

10. PMID: 29290508. Long B, Koyfman A. The emergency medicine evaluation and management of the patient with cirrhosis. Am J Emerg Med. 2018 Apr;36(4):689-698. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.12.047. Epub 2017 Dec 23.

11. PMID: 33942342. Biggins SW, Angeli P, Garcia-Tsao G, Ginès P, Ling SC, Nadim MK, Wong F, Kim WR. Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Management of Ascites, Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis and Hepatorenal Syndrome: 2021 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2021 Aug;74(2):1014-1048. doi: 10.1002/hep.31884.

12. PMID: 20583214. Sersté T, Melot C, Francoz C, Durand F, Rautou PE, Valla D, Moreau R, Lebrec D. Deleterious effects of beta-blockers on survival in patients with cirrhosis and refractory ascites. Hepatology. 2010 Sep;52(3):1017-22. doi: 10.1002/hep.23775.

13. PMID: 29290508. Long B, Koyfman A. The emergency medicine evaluation and management of the patient with cirrhosis. Am J Emerg Med. 2018 Apr;36(4):689-698. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.12.047. Epub 2017 Dec 23.

14. PMID: 12668984. Evans LT, Kim WR, Poterucha JJ, Kamath PS. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in asymptomatic outpatients with cirrhotic ascites. Hepatology. 2003 Apr;37(4):897-901. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50119.

15. PMID: 10673079. Rimola A, García-Tsao G, Navasa M, Piddock LJ, Planas R, Bernard B, Inadomi JM. Diagnosis, treatment and prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: a consensus document. International Ascites Club. J Hepatol. 2000 Jan;32(1):142-53. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80201-9.

16. PMID: 29992711. Oey RC, van Buuren HR, de Jong DM, Erler NS, de Man RA. Bacterascites: A study of clinical features, microbiological findings, and clinical significance. Liver Int. 2018 Dec;38(12):2199-2209. doi: 10.1111/liv.13929. Epub 2018 Aug 10.

17. PMID: 19897273. Soriano G, Castellote J, Alvarez C, Girbau A, Gordillo J, Baliellas C, Casas M, Pons C, Román EM, Maisterra S, Xiol X, Guarner C. Secondary bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis: a retrospective study of clinical and analytical characteristics, diagnosis and management. J Hepatol. 2010 Jan;52(1):39-44. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.10.012. Epub 2009 Oct 23.

18. PMID: 23190338. Deshpande A, Pasupuleti V, Thota P, Pant C, Mapara S, Hassan S, Rolston DD, Sferra TJ, Hernandez AV. Acid-suppressive therapy is associated with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients: a meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Feb;28(2):235-42.

19. PMID: 25460013. Ge PS, Runyon BA. Preventing future infections in cirrhosis: a battle cry for stewardship. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Apr;13(4):760-2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.10.025. Epub 2014 Nov 5.

Add comment