31 August 2020 by Shahriar Lahouti. Last update 7 February 2023.

CONTENTS

- Preface

- Anatomy and echocardiography of the right heart

- Physiology

- Definition

- Etiology

- Pathophysiology

- Clinical presentation

- Differential diagnosis

- Diagnostic evaluation

- Case scenarios

- Hemodynamic support of RV failure

- RECAP

- Going further

- Appendix

- Media

- References

Preface

For many years, the right heart has been downplayed as a bystander chamber. It has been accepted that the right heart is a conduit structure (dating back to the 16th century) that is a secondary actor in the interplay of heart failure, with primacy accorded to the left heart. Recent research efforts have uncovered that the right heart is structurally and physiologically discrete, with a distinct pathobiologic pathway in right heart failure.1

Right heart failure is a clinical syndrome caused by multiple causes. It is a formidable clinical challenge in both the ED and the Intensive care units. Uniquely, therapy that influences the left ventricle favorably may not impact the dysfunctional right ventricle and vice versa.

Anatomy and Echocardiography of the Right Heart

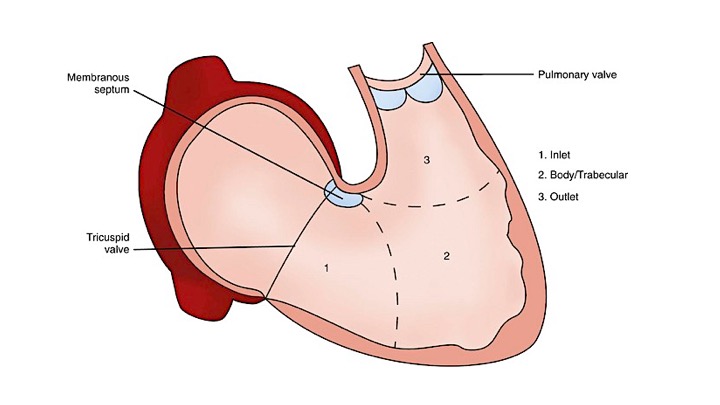

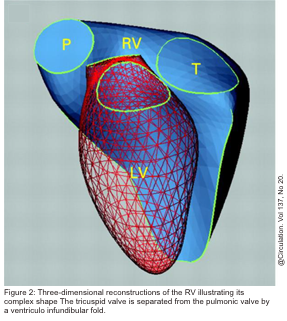

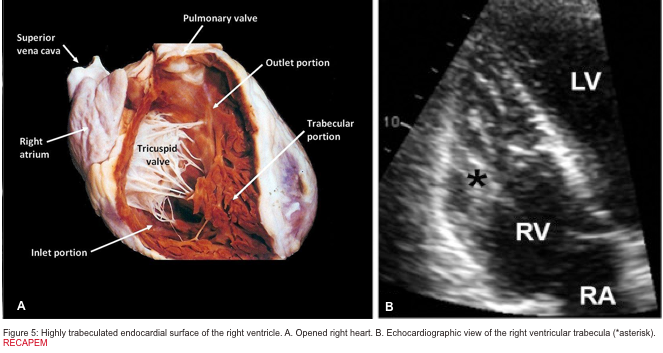

The right ventricle (RV) is anatomically composed of 3 distinct portions: the inlet, the apical myocardium, and the outlet.

- The first portion is the inlet, which includes the tricuspid valve,chordae tendineae, and papillary muscles.

- The second portion is the apical myocardium, which is prominently trabeculated

- The third is the outlet region (infundibulum or conus), including the pulmonary valve (figure 1)2,3.

Morphological features of the right ventricle that allow differentiation between the right and left ventricles are: 4

- Separate inflow and outflow tracts in the right heart, such that the tricuspid valve is not in continuity with the pulmonary valve, as opposed to the aortomitral continuity seen on the left side (figure 2 below).5

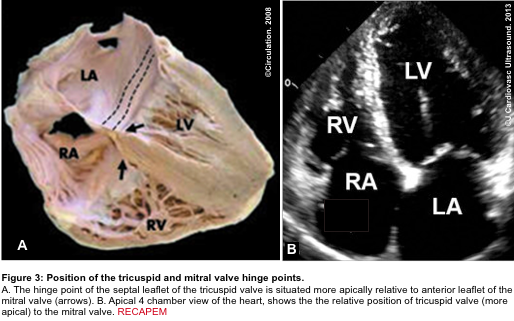

- A more apically situated hinge point of the septal leaflet of the tricuspid valve relative to the corresponding anterior leaflet of the mitral valve (figure 3 below).5

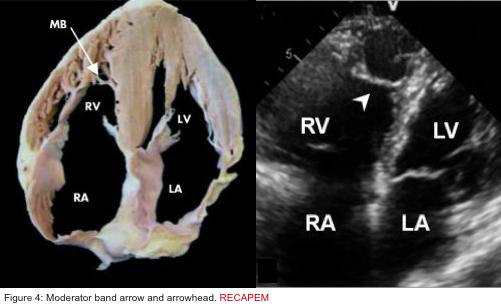

- Presence of the moderator band in the RV cavity (Figure 4 below):

- The moderator band (aka septomarginal trabecula) is a muscular band of heart tissue in the RV, extending from the base of the anterior papillary muscle to the ventricular septum. It carries part of the RBB to the anterior papillary muscle. This shortcut across the chamber of the RV Seems To Facilitate conduction time, allowing coordinated contraction of the anterior papillary muscle

- Highly trabeculated endocardial surface (figure 5).5

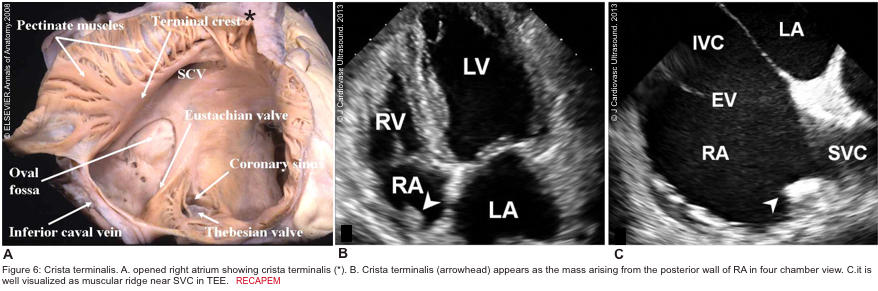

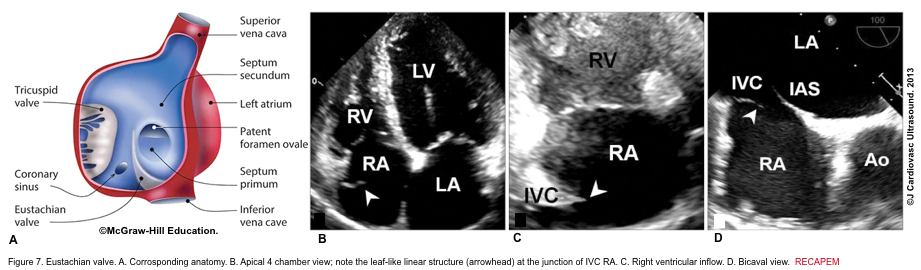

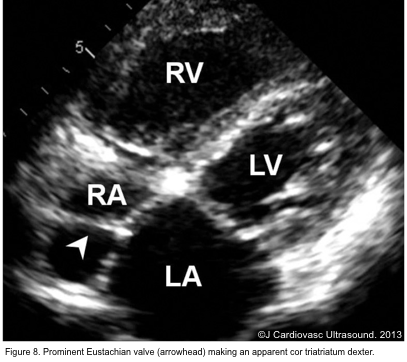

There are several discrete muscular ridges or bands in the right heart, which sometimes are mistaken for tumors or thrombi. These may include: 5 6

- Crista terminalis is a well-defined fibromuscular ridge that extends internally from the superior vena cava to the IVC along the lateral RA wall. It separates the RV inflow tract from the RV outflow tract. A prominent crista terminalis may be confused with an RA tumor on TTE (Figure 6).

- The eustachian valve is a remnant of the embryonic valve of the IVC. It appears as a crescent-like fold of variable size at the posterior margin of IVC (Figure 7). Occasionally, a prominent Eustachian valve appears to divide RA into two chambers, making apparent cor triatriatum dexter (figure 8).

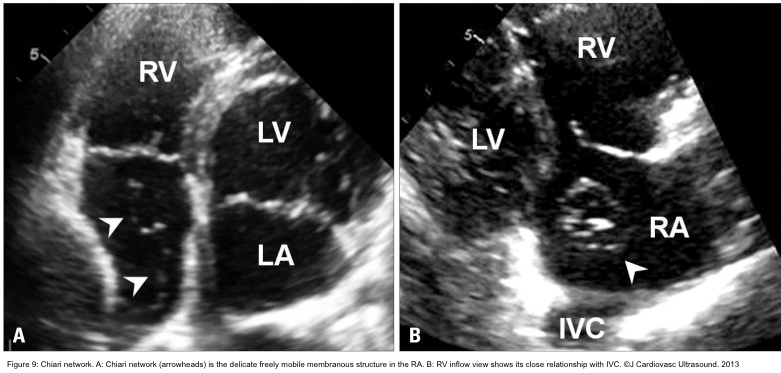

- The Chiari network is a thin, web-like fenestrated membrane that attaches along the ridge connecting the vena cavae and interatrial septum. It is found in 2-3% of normal hearts at autopsy. In echocardiography, the Chiari network appears as a free-floating curvilinear structure that waves with blood flow in the RA. A part of the Chiari network originates from the orifice of the IVC, similar to the Eustachian valve; however, the Chiari network is more mobile and thinner. In echocardiography, the Chiari network may be confused with tricuspid vegetation, flail tricuspid valve, free RA thrombus, and pedunculated tumors. Careful tracing to identify its attachment to the orifice of the IVC makes a differential diagnosis (Figure 9).

Physiology

Indeed, the LV and RV cannot be analyzed as separate entities, although they generally are; there are fibers that course between them at both superficial and deeper layers, and the two ventricles interact functionally. Given the anatomic discussions, it is perhaps spurious to discuss RV physiology as an independent phenomenon. This concept will be further explored in the section below regarding ventriculo–ventricular interactions. Nonetheless, the RV has a unique physiology, largely dependent upon the low hydraulic impedance characteristics of the pulmonary vascular bed.7

Mechanical Aspects of Ventricular Contraction

There are two layers of RV myocardium. The fibers of the superficial layer are circumferentially arranged, while the fibers of the deep muscle layer are longitudinally aligned.6

- RV relies on longitudinal fibers for ejection.

- In comparison, the LV also has an additional middle layer containing circumferential constrictor fibers that provide the main driving force of the LV by reducing ventricular diameter.

- Shortening of the RV is greater longitudinally than radially.

- In contrast to the LV, twisting and rotational movements do not contribute significantly to RV contraction. Moreover, because of the higher surface-to-volume ratio of the RV, a smaller inward motion is required to eject the same stroke volume.

Basic cardiovascular physiology and RV cardiodynamics

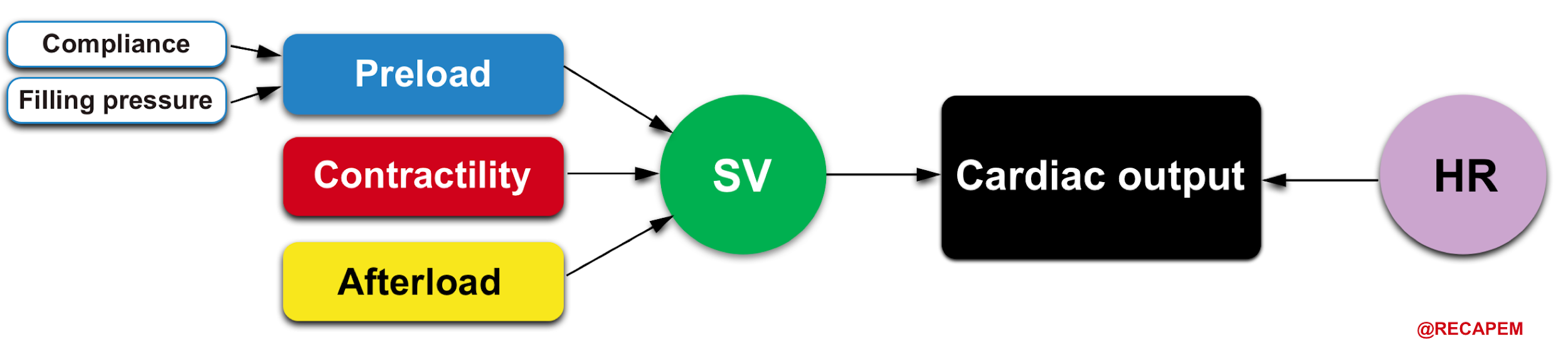

Systemic perfusion is defined by cardiac output (CO), which is the amount of blood pumped per minute from each ventricle.

- The product of heart rate (HR) and stroke volume (SV) determines cardiac output (CO= HR x SV).

- In physiologic states, RV cardiac output is equal to the LV cardiac output.8

- It should be evident from this relationship that all influences on cardiac output must act through changes in either the HR or the stroke volume (SV).

- SV is a measure of myocardial performance and is dependent on preload, contractility, and afterload. These relationships are shown below.

HR and myocardial contractility are strictly cardiac factors. They are characteristics of the cardiac tissues, although they are modulated by various neural and humoral mechanisms. Preload and afterload, however, depend on the characteristics of both the heart and the vascular system. Preload and afterload may be designated as coupling factors because they constitute a functional coupling between the heart and blood vessels.

A. Heart Rate(chronotropy)

- The autonomic nervous system is the main regulator of the HR.

- Tachycardia

- The maximum sinus rate is estimated as (220 minus age).

- The impact of tachycardia on the CO is not uniform.

- During a physiological stress response, tachycardia often results in the augmentation of CO. However, severe tachycardia may lead to decreased CO due to reduced diastolic filling time.

- Bradycardia

- The impact of bradycardia on ‘CO’ is more uniform, that is, pulling down the ‘CO’ within the whole range of its severity (more on this, here).

B. Determinants of stroke volume

- Contractility (inotropy)

- True contractility is defined as the inherent capacity of the myocardium to contract independently of loading conditions (preload or afterload). Since in practice, it is not possible to separate the impact of HR and loading conditions on contractility, the true contractility is not measurable.

- Contractility is increased in the healthy heart by:

- Adrenergic stimulation (via β1 and β2 receptors)

- Digitalis

- Inotropic agents

- Optimizing preload within physiologic range and lowering afterload can increase contractility as well. 4

- Preload:

- Represents the extent of precontraction myocardial fiber stretch, which is determined by the resting force, myocardial compliance, and the degree of filling.

- In vivo, it is the end-diastolic ventricular volume 9; however, due to its complexity in practice, intracardiac pressure is substituted, which can be determined more easily.

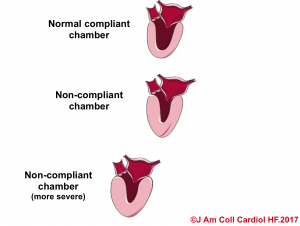

| In a non-compliant chamber (stiff chamber) there is no linear relationship between volume and pressure. Therefore, in clinical conditions such as right or left ventricular hypertrophy, where the chambers’ compliance is altered, Measures such as CVP or PCWP are not accurate for their corresponding chamber preload. |

-

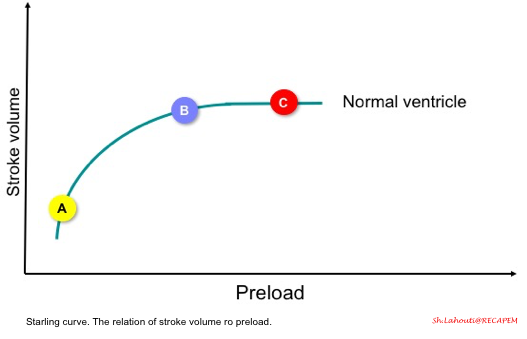

- The starling curve (figure below) illustrates the relationship between stroke volume and preload.

- In a normal heart, if the ventricles are operating on a steep part of the curve, then increasing preload (points A to B) results in increasing stroke volume (called a preload-dependent state).

- However, if the ventricles are operating on a flat part of the curve (point C), increasing preload does not result in increasing stroke volume (called a preload-independent state).

- The starling curve (figure below) illustrates the relationship between stroke volume and preload.

-

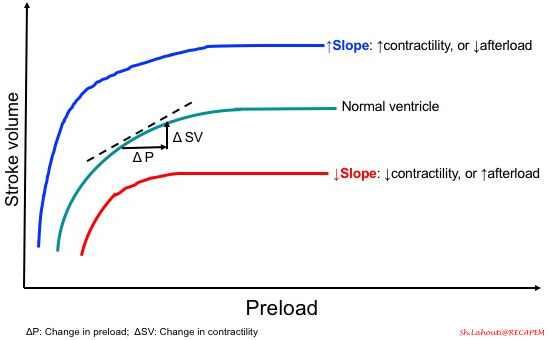

- As mentioned before, cardiac output not only depends on preload, but also contractility and afterload are other players at the table. Therefore, the slope of the curve is determined by these two parameters, as shown in the following figure.

-

- What factors can impact RV preload?

- Compliance with the right atrium and ventricle, filling pressure, heart rate, and rhythm can influence the RV preload. In terms of compliance, the right ventricle is more compliant than the left ventricle.

- Chamber compliance:

- Compliance is the ability of a hollow organ to distend and increase volume with increasing transmural pressure. This concept is illustrated in the following examples.

- #1: You have a beach ball and a balloon. Which one is easier to blow up?

- True. For sure, the balloon is easier as it’s soft, thinner, and more extensible.

- #1: You have a beach ball and a balloon. Which one is easier to blow up?

- Compliance is the ability of a hollow organ to distend and increase volume with increasing transmural pressure. This concept is illustrated in the following examples.

- What factors can impact RV preload?

-

-

-

-

- In hypertensive heart disease, the left ventricle becomes thickened and muscularized as an adaptive response to the high systemic vascular resistance. This makes the LV less distensible (like the beachball), and therefore, for the same amount of volume in the diastole, the end-diastolic pressure would be higher. That is to say, the LV is noncompliant as shown below.10

-

-

-

-

-

-

- #2: In another example, you have two balloons, but one in the bottle. Which one is easier for blowing up?

-

-

-

-

-

-

- The balloon in the bottle is more difficult since you should blow up against the opposite force that the bottle is exerting on the balloon.

- Likewise, in pericardial disease, the distensibility of the cardiac chamber is limited due to the impact of pericardial constraint. In such conditions, the intracardiac pressure (end-diastolic pressure) is increased to stand against the raised intrapericardial pressure.

-

-

-

3. Afterload

- Refers to the total resistance to ejection of blood from the ventricle during contraction.

- Increasing afterload results in decreased extent and velocity of myocardial contraction.

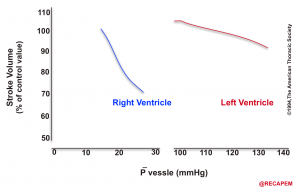

- The heart is a double power generator. The RV and the LV both propel blood into circulation, and each is well adapted to its respective outflow system, called ventriculo-arterial coupling.

- These unique physiologic and anatomic features of the right heart make it extremely poorly tolerant to pressure overload states, e.g., pulmonary embolism(especially if sudden).

- This is in contrast to the biological design of the left heart, which is intended for a distinct purpose. The LV myocardium is thick and well-adapted to a high-pressure system on an evolutionary scale, making it tolerable to pressure overload.

- The response of the RV and LV to an experimental increase in afterload is shown below.11

Ventricular Interdependence

Ventricular interdependence refers to the concept that the size, shape, and compliance of one ventricle may affect the other ventricle through direct mechanical interactions.8

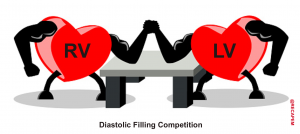

- Since the heart is enclosed by the pericardium, there’s limited space for distension during diastole. In simple words, the ventricles compete for diastolic filling as illustrated below!

- In acute RV pressure or volume overload states, dilatation of the RV shifts the interventricular septum toward the left.

- As a consequence, the LV distensibility during diastole is impaired, which potentially leads to an ↓LV preload or low cardiac output state.

Heart-Lung Interaction

With each inspiration, the small change in intrapleural pressure (more negative pressure) leads to a significant increase in venous return, RV preload, and consequently, RV cardiac output.8

- During positive pressure ventilation, as the mean airway pressure is increased, there is a fall in RV cardiac output due to two factors: reduced venous return and, secondly, worsening RV systolic function (this explains the afterload dependency of the RV contractile performance).

- That is to say, when the lungs are under pressure, the heart is under pressure too, as illustrated below.

Perfusion of the right ventricle

Why is it so crucial to understand the RV perfusion principle?

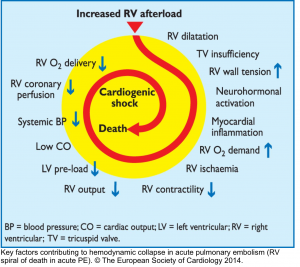

- The basic principle of the pathogenesis of RV failure is that regardless of the types of inciting etiology (e.g., volume/pressure overload, or ischemia), a Vicious Cycle (RV spiral of death) is started and RV malperfusion is reinforced through complex chains of events, culminating in cardiogenic shock and death.

- This principle underlies the fact that management of patients with ‘acute right heart failure’ is challenging, and inappropriate therapeutic interventions are unforgivable.12

- The heart is supplied by the coronary arteries. When oxygen supply does not meet the demand, myocardial ischemia occurs, and cardiac performance is threatened.

- LV is a pressure pump, i.e., the LV end-systolic pressure is high; therefore, LV perfusion occurs during diastole alone.

- In contrast, RV is a volume pump, and the end-systolic and diastolic pressure within the RV are low enough to make perfusion possible during both systole and diastole.13

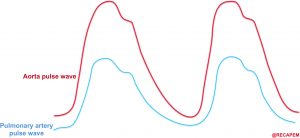

- Perfusion pressure within the right coronary artery is equal to (aortic pressure minus pulmonary arterial pressure). .14

- The aortic and pulmonary arterial pulse waves are illustrated below. The gap between these two represents the perfusion pressure within the right coronary artery.

- 👉An essential goal in the hemodynamic management of patients with acute right heart failure is to maintain systemic blood pressure above pulmonary arterial pressures, thereby preserving right coronary blood flow.

Definition

Heart failure vs. cardiac dysfunction

- The term Heart failure should not be conflated with cardiac dysfunction.

- Heart failure is a clinical syndrome in which signs and symptoms are caused by impaired ventricular filling or reduced ventricular flow output.

- Cardiac dysfunction refers to abnormalities in intrinsic chamber performance, e.g., diastolic dysfunction or systolic dysfunction; however, patients may have RV or LV dysfunction but do not manifest signs and symptoms of poor tissue perfusion or congestion.17

Etiology

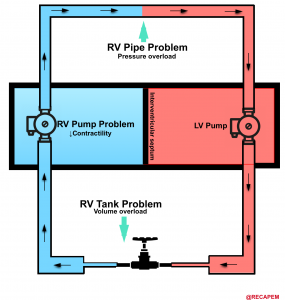

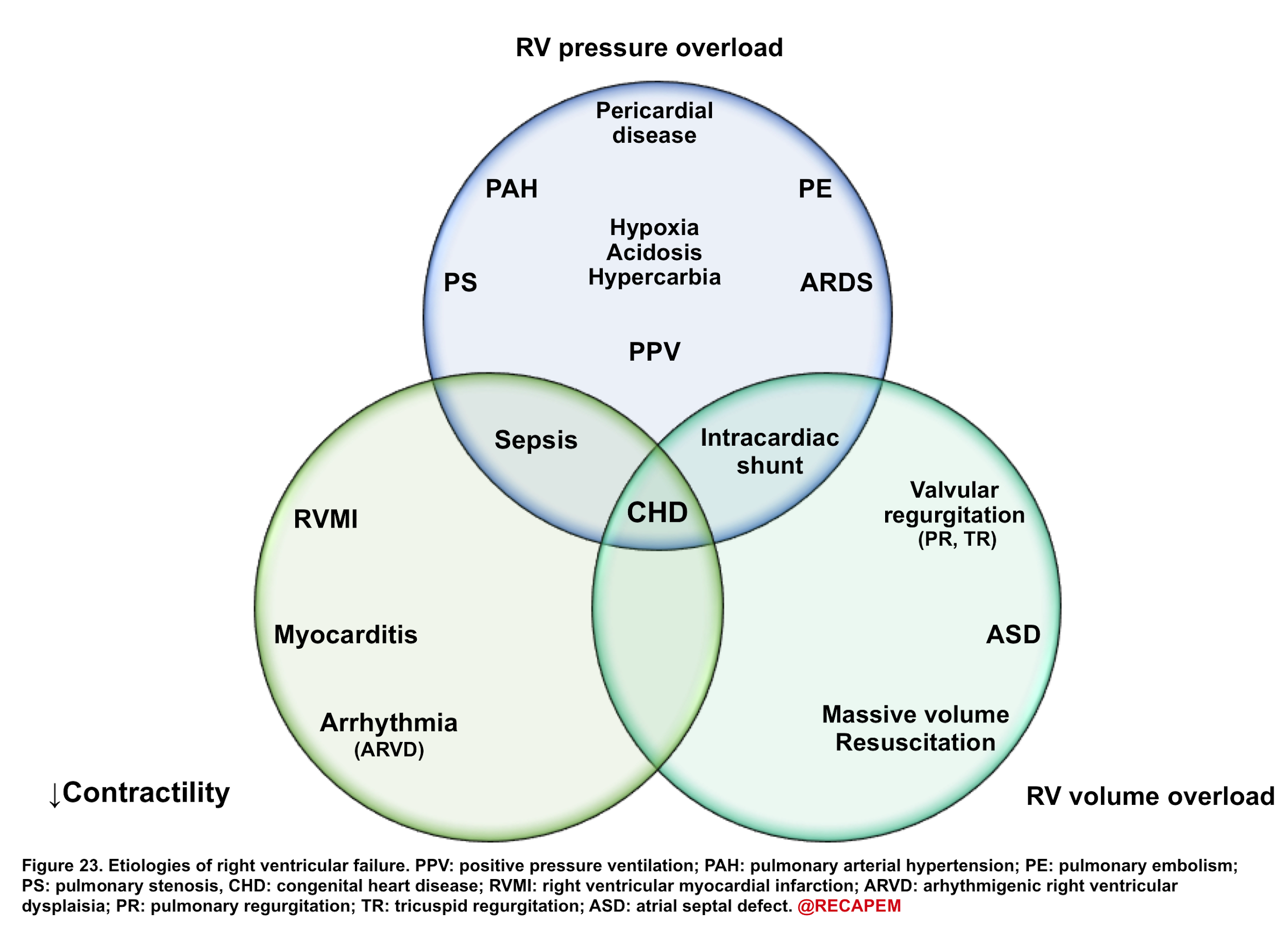

The RV performance integrates preload, afterload, and contractility (figure below). RV mechanics and functions are altered in the setting of pressure, and or volume overload as well as in the primary reduction of myocardial contractility. 15

- The most common cause for RV dysfunction/failure is pressure overload (e.g., pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary embolism), with decreased contractility and RV volume overload in the second and third place, consequently 15. Etiologies for RV failure are represented in the following figure.

◾️Generally, etiologies of right ventricular failure can be grouped as:

- Causes of chronic pulmonary hypertension.

- Causes of right ventricular myocardial dysfunction/decompensation

- Volume overload (excessive preload)

- Hypervolemia.

- Tricuspid regurgitation (e.g. tricuspid endocarditis).

- VSD (ventricular septal defect).

- Primary RV myocardial dysfunction

- Right ventricular myocardial infarction (RVMI).

- Septic cardiomyopathy

- Myocarditis

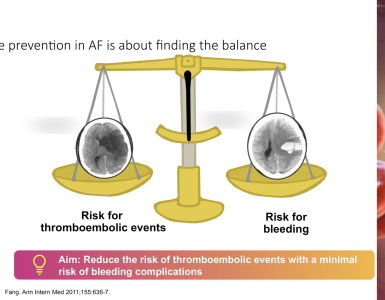

- Arrhythmia (e.g. atrial fibrillation, bradycardia).

- Negative inotropic medications, e.g. β-blockers, diltiazem, verapamil.

- Volume overload (excessive preload)

- Causes of acute pulmonary hypertension.

- Pulmonary embolism (PE)

- Massive PE can cause acute-onset pulmonary hypertension.

- Moderate-sized PE may cause decompensation among patients with chronic pulmonary hypertension.

- Lung disease (e.g. any cause of hypoxemia and/or hypercapnia)

- Nonadherence with pulmonary hypertension therapy.

- Pulmonary embolism (PE)

Pathophysiology

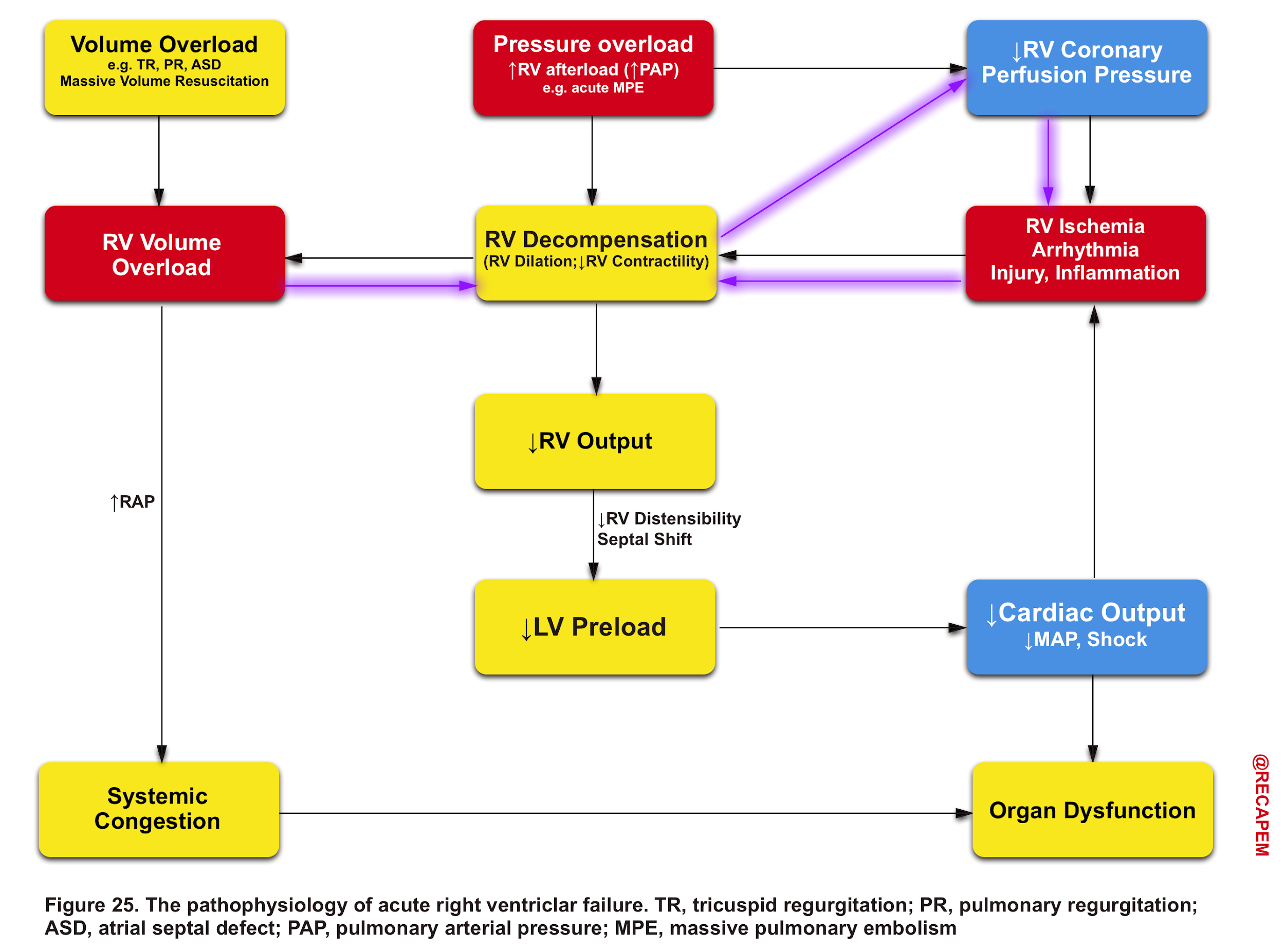

The pathophysiology of the primary insults to the right heart and their relevant evolution within the course of the disease process is illustrated below (Figure 25).

Any type of primary insult will further deteriorate RV performance via downward complex chains of events that reinforce themselves through a feedback loop (Vicious Cycle),16 and if not timely intervened, cardiovascular collapse and death will be the outcome.

Pressure overload

- The thin-walled RV is not built to handle large or sudden increases in pulmonary arterial pressure.16

- In the setting of acutely increased afterload, the RV responds by increasing its contractility, but RV failure may occur rapidly if these mechanisms prove unable to generate sufficient pressure to maintain flow.

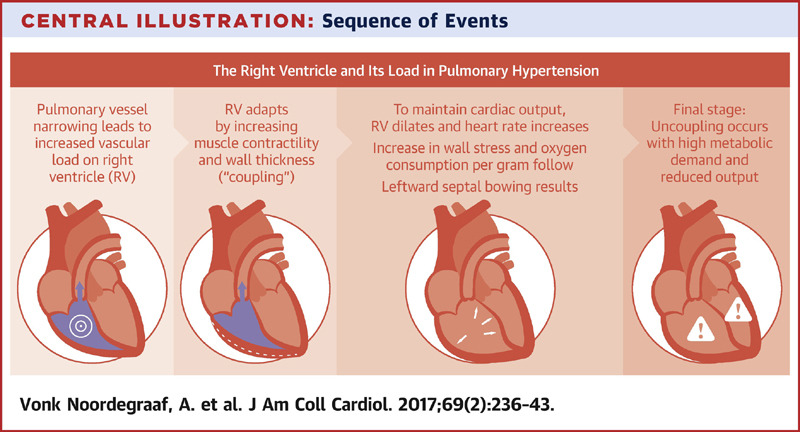

- In chronically evolving pulmonary hypertension, the RV responds to increasing afterload with progressive hypertrophy, which allows it to maintain cardiac output at rest over long periods. Finally, the RV dilates in end-stage disease, leading to tricuspid regurgitation and, ultimately, decreased cardiac output. Acute decompensation of chronic pulmonary hypertension may lead to a clinical presentation barely distinguishable from that of ‘truly’ acute RV failure, as, for example, in acute pulmonary embolism.

- The consequence of pulmonary hypertension on the right ventricle is illustrated in the figure below.

Volume overload

- By and large, the RV is more tolerant to volume overload (relative to pressure overload).

- However, following RV dilation, myocardial perfusion is impaired (purple arrows in Figure 25), and consequently, a vicious cycle is inevitable if not timely intervened.16

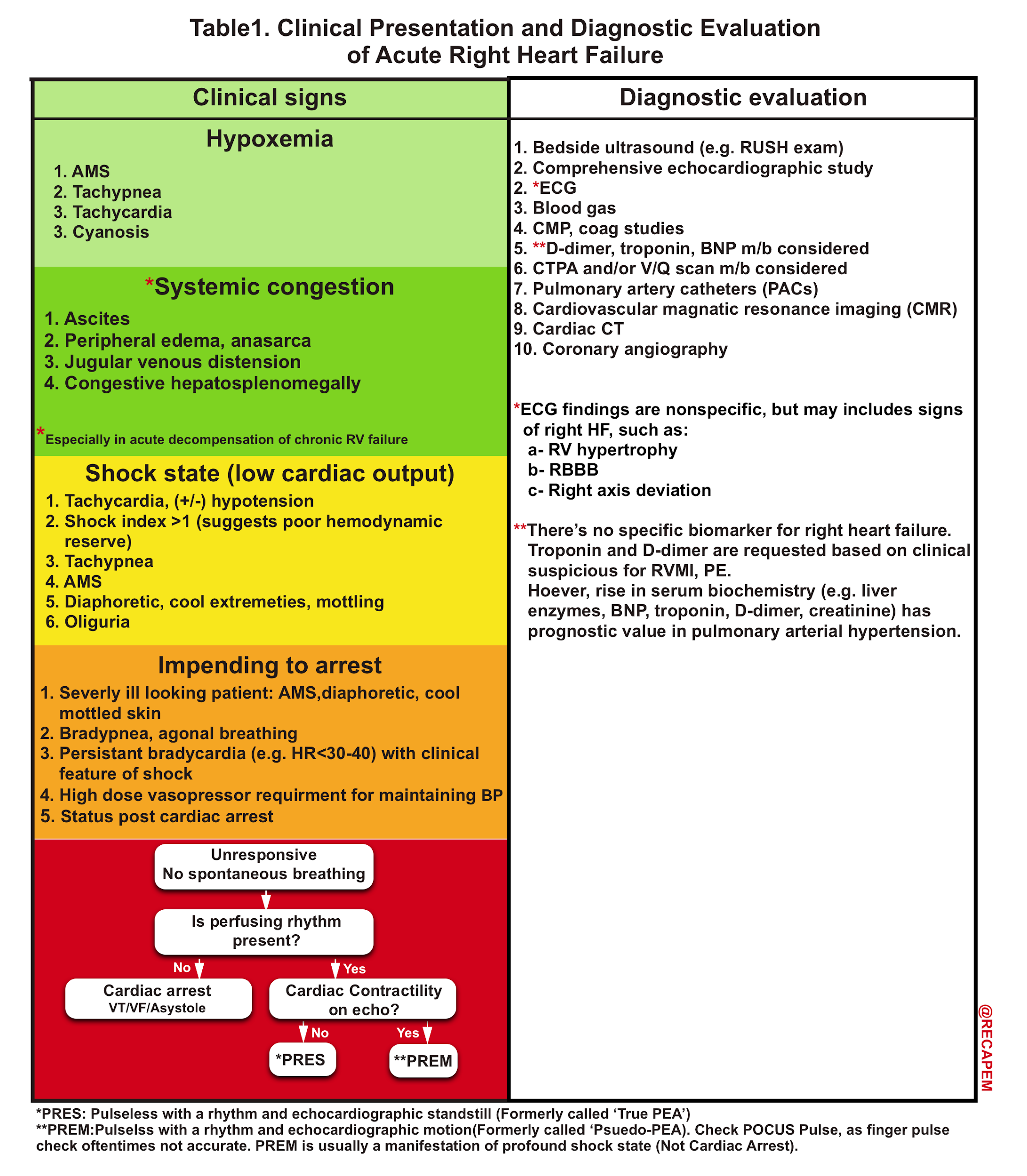

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation of acute RV failure varies depending on the underlying cause, severity, and acuity of the disease, as well as the presence of comorbidities.16 For this post, clinical presentation and diagnostic evaluation are summarized here (Table 1).

Differential Diagnosis

DDx of shortness of breath with dry lungs

- Acute coronary syndrome

- Pulmonary embolism (more on this, here)

- Cardiac tamponade (see here)

- Pre-capillary pulmonary hypertension (more on this, here)

- Anemia, a metabolic disorder, e.g., DKA

DDx of shortness of breath with dry lungs, but in the presence of peripheral congestion

- Precapillary pulmonary hypertension

- Cirrhosis

- Nephrotic syndrome

- Constrictive pericarditis

- Superior vena cava syndrome

DDx of shortness of breath with wet lungs

- Postcapillary pulmonary hypertension (more on this, here)

- Combined pulmonary hypertension

- HFrEF

- HFpEF

- Pneumonia

- ARDS (see here)

Diagnostic evaluation

Labs

- Complete metabolic profile, coagulation study, and blood gas analysis. Possible findings include

- Hypoxaemia, acidosis, hyperlactatemia, acute renal failure, transaminitis, mild coagulopathy, and hyperbilirubinemia.

- BNP, Troponin, and D-dimer may be considered based on clinical suspicion for RVMI and PE.

ECG

💡Findings of acute and chronic RV strain can be similar. Previous ECGs and clinical context are required to differentiate between these two possibilities.

- Acute right ventricular strain

- Complete or incomplete RBBB

- Terminal right-axis deviation

- Prominent terminal S-wave in Lead I.

- Prominent S-wave in V6 (normally, V6 has no S-wave).

- T-wave inversion

- Right precordial leads.

- Inferior leads (III > aVF).

- ST changes, in severe cases.

- STE in III and aVF, +/- anteroseptal leads.

- Diffuse ST depression with ST elevation in aVR.

- Right precordial ST depression can mimic a posterior MI.

- Chronic right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH)

- Tall R-wave in V1

- Defined as R>S, or R>7 mm.

- Highly specific for RVH, but insensitive.

- Terminal right-axis deviation

- Prominent terminal S-wave in Lead I.

- Prominent S-wave in V6 (normally, V6 has no S-wave).

- Right atrial abnormality (especially increased P-wave amplitude in Lead II)

- RV strain pattern: ST depression, T-wave inversion in V1-V4, and to a lesser degree in the inferior leads.

- Tall R-wave in V1

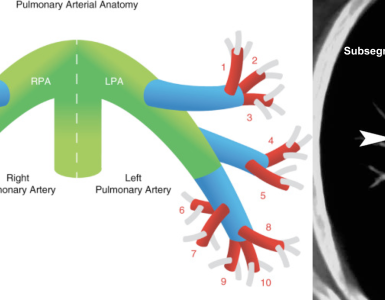

Chest imaging: CT, CTPA

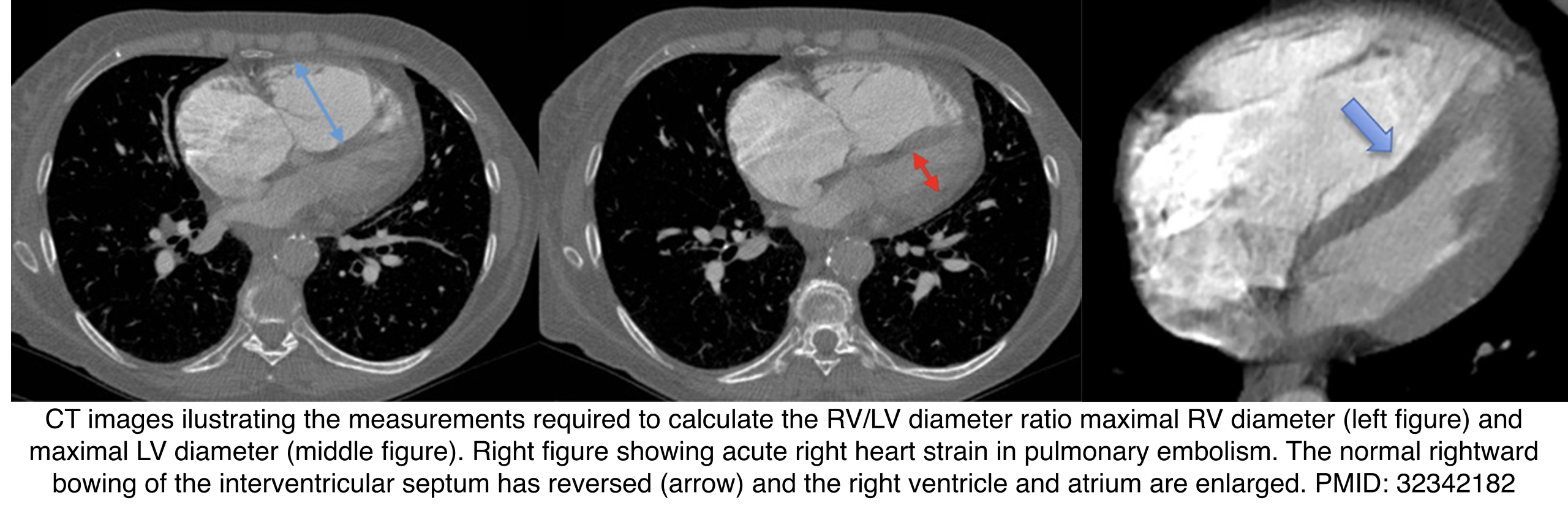

◾️RV dilation

- RV > LV ratio suggests RV dilation. Measure maximal diameters of both ventricles (may require multiple CT slices).

- Measured in a plane perpendicular to the septum.

- Limitation: Less reliable in patients with LV enlargement.

- ⎮Transverse diameter >57 mm in females or >60 mm in males

- Performance: ~65% sensitivity, ~92% specificity.

- Septal bowing: Leftward bowing of the interventricular septum can occur in acute PE or chronic pulmonary hypertension.

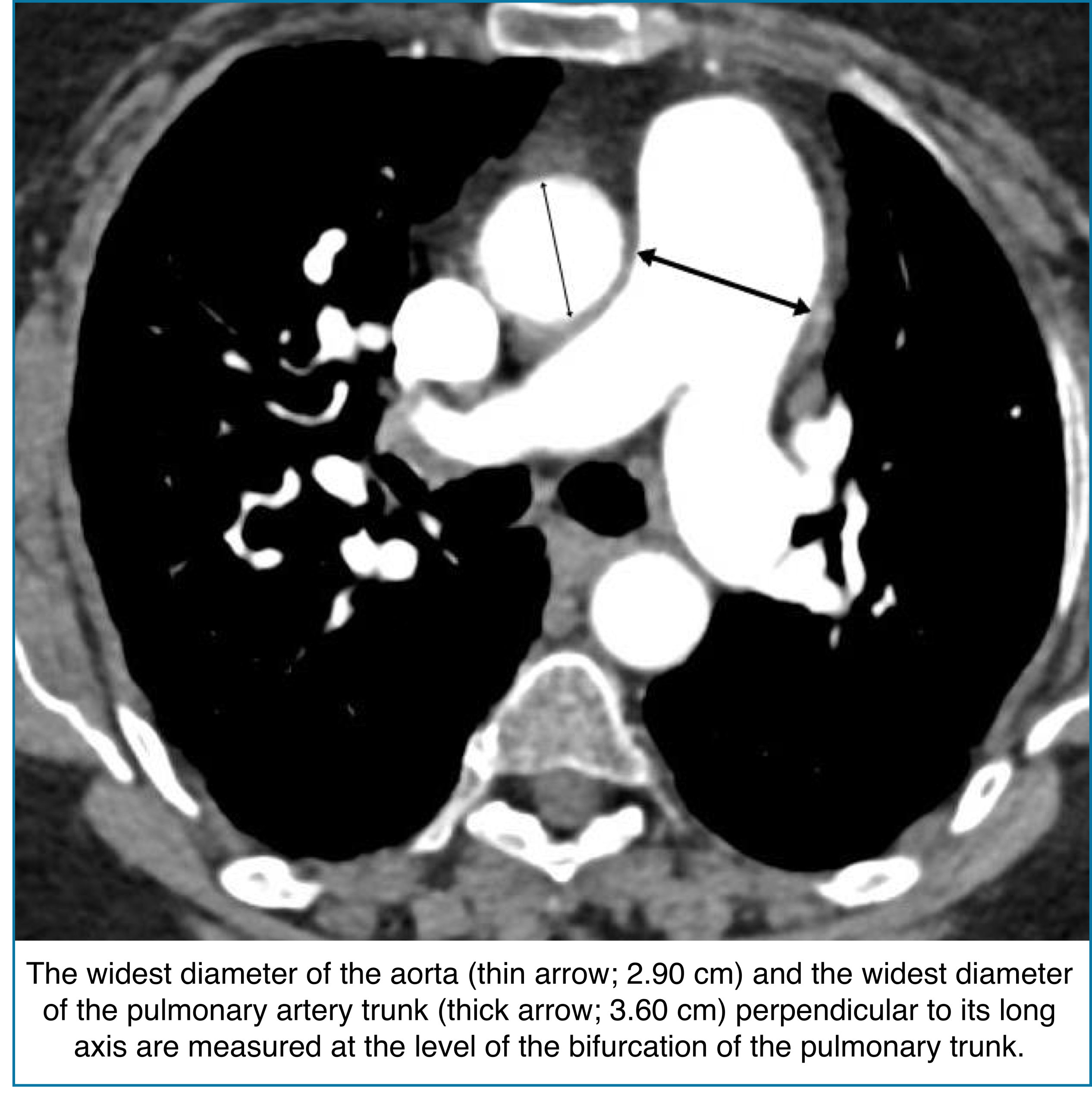

◾️Pulmonary artery dilation

- Pulmonary artery enlargement on CT can signal elevated pulmonary pressures, often reflecting chronicity and severity of pulmonary hypertension. However, it may be absent in acute RV failure, so interpretation must consider the clinical context.

- Key Pearls

- Pulmonary artery)/(aorta) ratio >1.

- This ratio has a fairly high specificity for identifying pulmonary hypertension (~90%).

- The ratio is inaccurate among patients with aortic dilation (more likely in older patients).

- Absolute PA diameter >3 cm → Consistent with PA dilation.

- Specificity may be enhanced by using a cutoff of >32.5 mm.

- Pulmonary artery)/(aorta) ratio >1.

- Clinical significance:

- Tracks with severity and duration of pulmonary hypertension.

- It may be normal in acute right ventricular failure.

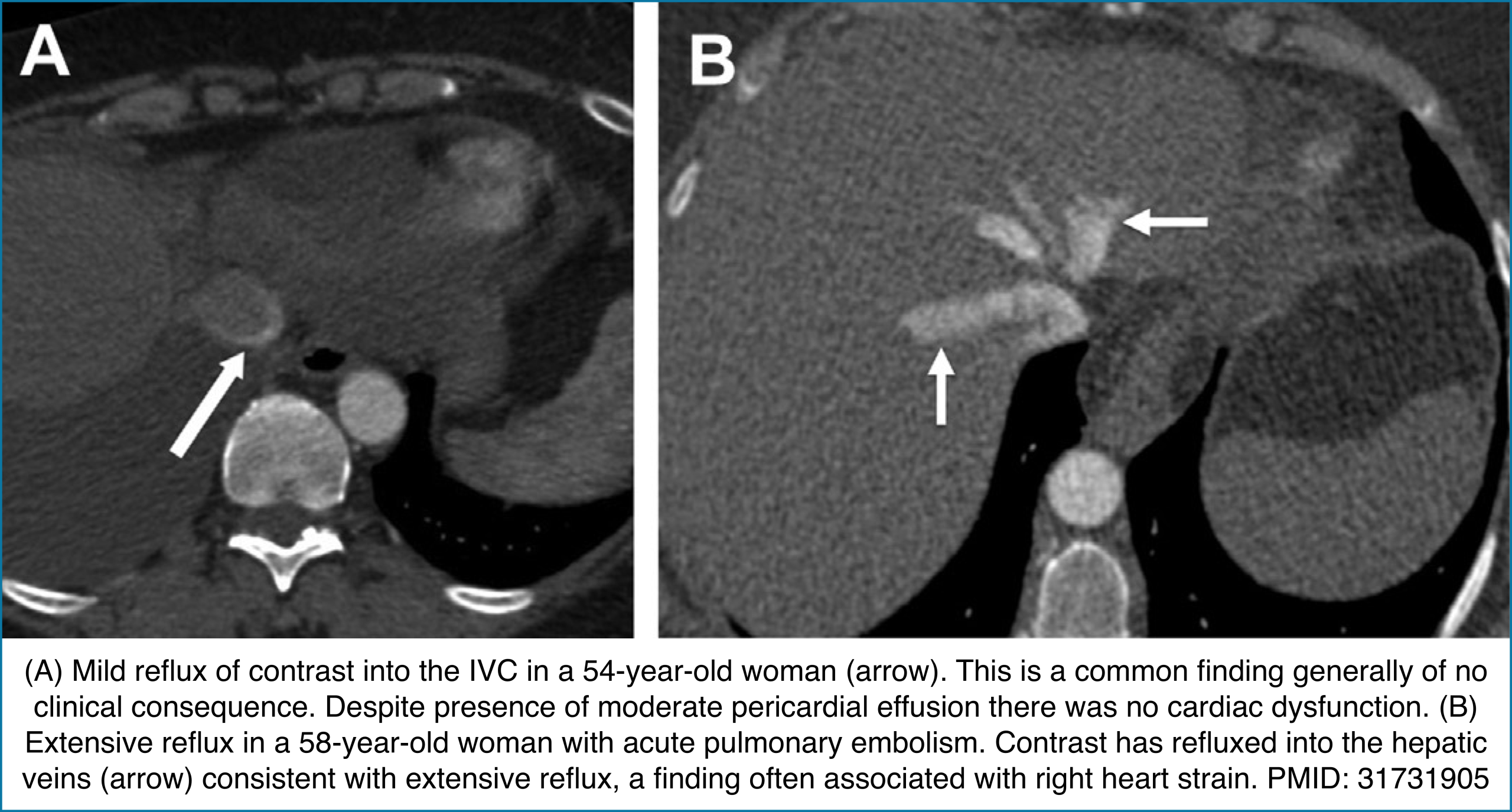

◾️Contrast reflux into the inferior vena cava and hepatic veins

- Reflux of contrast from the right atrium into the IVC can indicate impaired right ventricular forward flow. While it may occur with PE, tricuspid regurgitation, or pericardial disease, its diagnostic value is heavily influenced by injection technique.

- Key Pearls

- Contrast reflux → Suggests RV failure from causes such as PE, TR, or pericardial pathology.

- Diagnostic performance varies with injection rate:

- <3 mL/s (routine CT): ~31% sensitivity, ~98% specificity.

- >3 mL/s (CTA): ~81% sensitivity, ~69% specificity.

◾️Pericardial effusion

- Pericardial effusion has a broad differential, but when seen in the setting of right ventricular failure, it often indicates long-standing, severe pulmonary arterial hypertension. Its presence reflects chronic pressure overload rather than acute RV dysfunction.

- Key Pearls

- Pericardial effusion + RV failure → Suggests chronic, severe pulmonary arterial hypertension.

- Additional details are covered in the echocardiography section below.

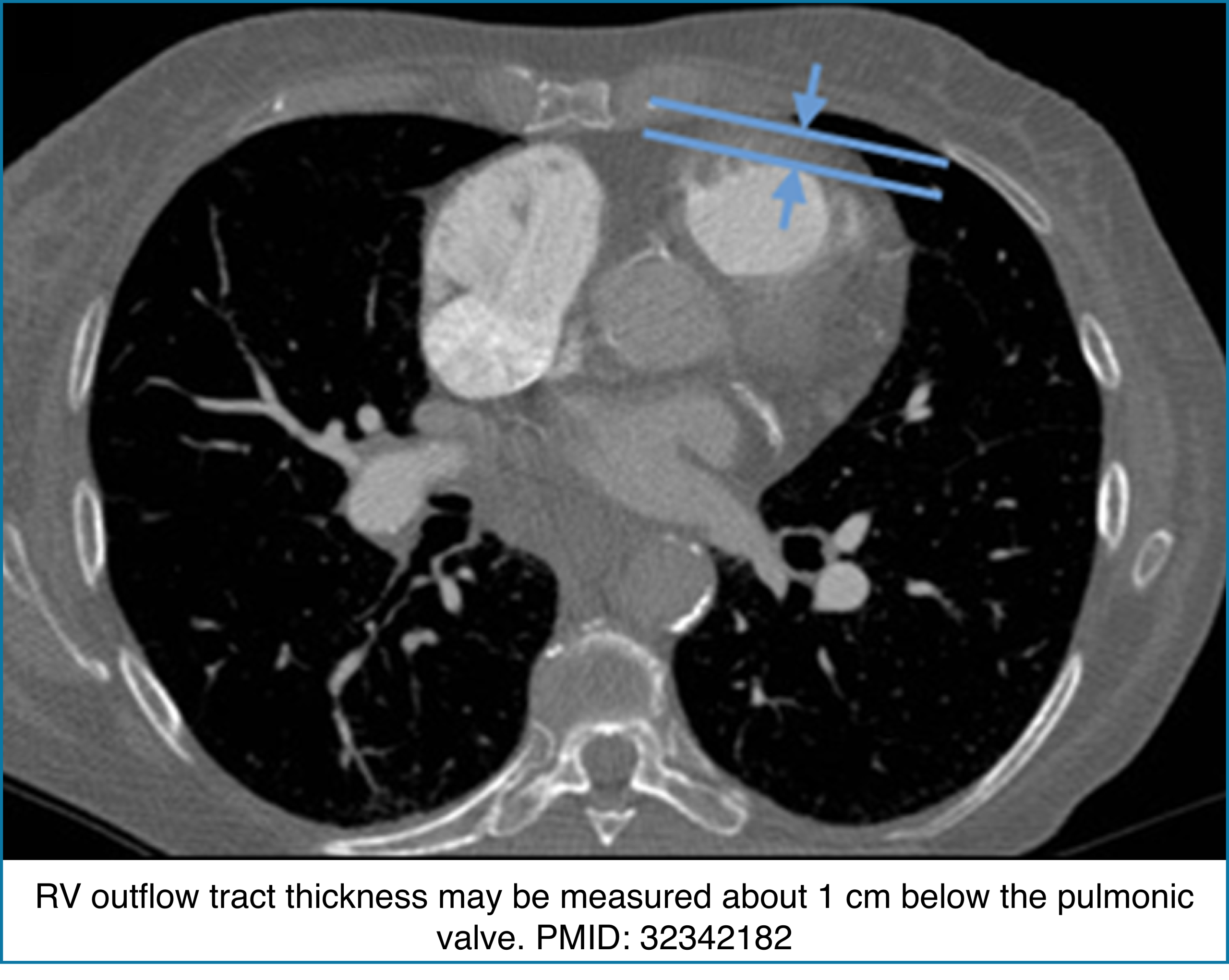

◾️Right Ventricular Wall Thickness

- The RV normally has a very thin free wall that is often difficult to appreciate on CT. When the RV outflow tract becomes visibly thickened, it usually reflects chronic pressure overload rather than acute pathology.

- Key Pearls

- Normal RV wall: Thin, ~3 mm, often barely visible on CT.

- RVOT thickness >6 mm: Suggests chronic pulmonary hypertension.

◾️CT Evidence of Congestive Hepatopathy

- Congestive hepatopathy reflects chronic venous congestion from right-sided heart failure. CT findings help distinguish it from cirrhosis and other liver pathologies.

- Key Pearls

- Hepatomegaly is common (sometimes massive); splenomegaly is usually absent unless the disease has progressed to cirrhosis.

- Ascites in ~25%, typically mild and often present without cirrhosis *.

- CT pattern: Speckled, heterogeneous enhancement on contrast phases.

- Hypervascular nodules resembling FNH may appear; differentiate carefully due to increased HCC risk.

- Portosystemic shunts are usually absent because venous pressures are elevated throughout *.

⎮Note:

- Pleural effusions: It can occur with RV failure and pulmonary hypertension, but is a non-specific ancillary finding and should be interpreted alongside RV size, function, TR velocity, IVC/RA measures, and hemodynamics.”

- “Pleural effusion = possible sign of RV failure/PH — helpful contextually, not diagnostic alone (2025 ASE).”

Bedside ultrasound

Click to enlarge the image

Patients with acute right heart failure are critically ill and often have multiple comorbidities. Oftentimes, definitive diagnosis and implementation of specific treatment is time-consuming. While the simultaneous employment of resuscitative and diagnostic measures (table above) is warranted for critically ill patients, the crucial role of bedside echocardiography cannot be overemphasized.

- POCUS can facilitate the diagnostic process and is often helpful in therapeutic decision-making. It can be used to exclude extrinsic causes of acute RV failure, especially those that require immediate treatment (such as pericardial tamponade, which mimics acute RV failure).

- The recommended conventional echocardiographic measures for the evaluation of right heart structures and function are summarized here.

RV dilation

- RV internal diameter: This can be evaluated at the widest point of the right ventricle in diastole in a standardized apical four-chamber plane *.

- Normally, the RV is <~60% the size of the LV.

- Moderate RV dilation: RV is ~60-100% the size of the LV.

- Severe RV dilation: The RV is larger than the LV.

- Right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) proximal diameter (PLAX view).

- Abnormal value: ROVT diameter > 27 mm.

RV septal flattening (D-sign)

- The D-sign refers to interventricular septal flattening seen in parasternal short-axis views of the heart.

- RV septal flattening in diastole suggests volume overload.

- RV septal flattening in systole suggests pressure overload (e.g., pulmonary hypertension).

- RV septal flattening throughout the diastole and systole suggests a combination of both volume and pressure overload (often seen in severe pulmonary hypertension).

TAPSE (tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion)

- TAPSE is a measurement of longitudinal systolic performance of the right ventricle.

- Measurement: 2D A4C view. The M-mode cursor is directed through the lateral annulus of the tricuspid valve, and the distance of annular motion during systole is measured longitudinally.

- Grading:

- Normal value > 16-20 mm.

- Mild RV dysfunction: 11-15mm

- Moderate RV dysfunction: 6-10mm

- Severe RV dysfunction: <5mm

Right atrial pressure (RAP) based on the inferior vena cava (IVC)

- Normal range: 2-6 mm Hg (measured by central venous catheterization).

- RAP based on IVC:

- IVC size < 2.1cm with collapsibility > 50%: RAP 0-5 mm Hg.

- IVC size >2.1 cm with collapsibility > 50%: RAP 5-10 mm Hg.

- IVC size > 2.1 cm with collapsibility <50%: RAP 10-20 mm Hg.

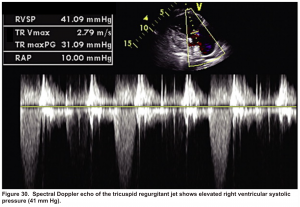

Pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP)

- PASP = RAP + 4(TR jet velocity in m/s)2

- It can be estimated based on the maximal tricuspid regurgitant (TR) jet velocity, using continuous wave Doppler (CWD) placed across the tricuspid valve plus right atrial pressure (RAP).

- Pulmonary hypertension is highly likely if PASP >35 mm Hg (or a tricuspid jet velocity >3.4 m/s); OR if the TR jet is 2.9-3.4 m/s in the context of other echocardiographic features of right ventricular dysfunction *. More on this here.

Bubble study to evaluate refractory hypoxemia

- Severely elevated right-sided pressure (e.g., severe pulmonary hypertension, massive PE *) can cause severe refractory hypoxemia that may reflect some degree of shunt.

- The differential diagnosis of hypoxemia includes:

- Right-to-left shunt via PFO: Elevated right-sided pressure leads to opening up a patent foramen ovale (PFO), with subsequent intracardiac shunting of deoxygenated blood into the systemic circulation (right-to-left shunting).

- Coexistent pulmonary disease (chest CT may be helpful to identify other coexistent etiologies).

- Assessing right-to-left shunt

- To assess for right-to-left shunt, an A4C is observed while 10 mL of agitated saline is bolused.

- The appearance of bubbles in the left ventricle within 3-6 beats after the appearance of bubbles in the right ventricle indicates an intracardiac shunt *.

- If bubbles appear after 6 beats and the RA is free of bubbles, this suggests pulmonary arteriovenous malformations.

- To assess for right-to-left shunt, an A4C is observed while 10 mL of agitated saline is bolused.

- The presence of a right-to-left shunt should trigger more aggressive reduction of pulmonary artery pressures (e.g., inhaled pulmonary vasodilators, vasopressors to increase the systolic/pulmonary pressure gradient, diuresis).

Signs of chronic pulmonary hypertension

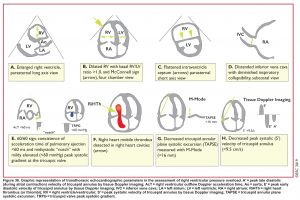

Echocardiographic signs in pulmonary embolism

- Overall, the sensitivity of TTE for the diagnosis of PE is about 50-60% while the specificity is around 80-90%. TTE is normal in about 50% of unselected patients with acute PE, but it can provide direct and/or indirect evidence for the diagnosis.

- In patients with suspected high-risk PE presenting with shock or hypotension, the absence of echocardiographic signs of RV pressure overload and/or dysfunction virtually excludes massive PE as a cause of hemodynamic instability.

- When PE is diagnosed, echocardiography can be used to differentiate those patients not at high risk into intermediate risk (evidence of RV dysfunction) vs. low risk (no RV dysfunction).

- Echocardiographic findings in acute PE are illustrated in Figure 36 below.29

Direct signs for PE: Clot in transit defined as a large, mobile (i.e. unattached to any intracardiac structure), serpentine echogenicity trapped in the right heart chambers or pulmonary artery is rare (sensitivity 13%), but makes the diagnosis evident (specificity 97%) 29.

Clot in transit

Indirect signs for PE (though nonspecific)

- Systolic/diastolic septal shift (D-shaped left ventricle).

- Dilatation of RA, RV (end-diastolic RV/LV diameter 0.6 or area 1.0). See below.

- Global RV hypokinesia

- McConnell sign: RV hypokinesia sparing the apex.

- It is not specific (specificity 82%) for PE and can be seen with RVMI as well. It has poor sensitivity (~45%) 29.

- Pulmonary hypertension is around 40-50 mmHg (>60 mmHg in the case of pre-existing pulmonary hypertension). 👉See here.

- Mild to severe TR: Secondary TR is frequent in patients with intermediate to high-risk PE, allowing estimation of pulmonary arterial systolic pressure (PASP).

- As the RV is only able to generate a PASP of up to 60 mmHg acutely, in the acute setting, the TR jet velocities are expected to be no higher than 2.5-3.5 m/s, corresponding to a PASP of about 40-50 mmHg in acute PE.

- Conversely, a PASP of 60 mmHg may suggest a more chronic process, relating to repeated episodes of PE, or chronic pulmonary parenchymal disease and/or superimposed PE.

- Pulmonary acceleration time < 60 ms is in favor of PE. 👉See here.

- Pulmonary systolic notch: A Normal pulmonary systolic flow pattern has no notching. As pulmonary vascular resistance is increased, the Doppler flow wave will reflect backward to the RV during systole, which impedes RV ejection and causes the Doppler envelope notching. The presence of early systolic notching (ESN) indicates mildly elevated mean PAP (the notch is defined early if it falls within the initial 50% of the ejection time). Moreover, the presence of ‘ESN’ identifies patients with Massive or submassive PE.

McConnell’s sign: Hypokinesis of the RV with sparing of the apex.

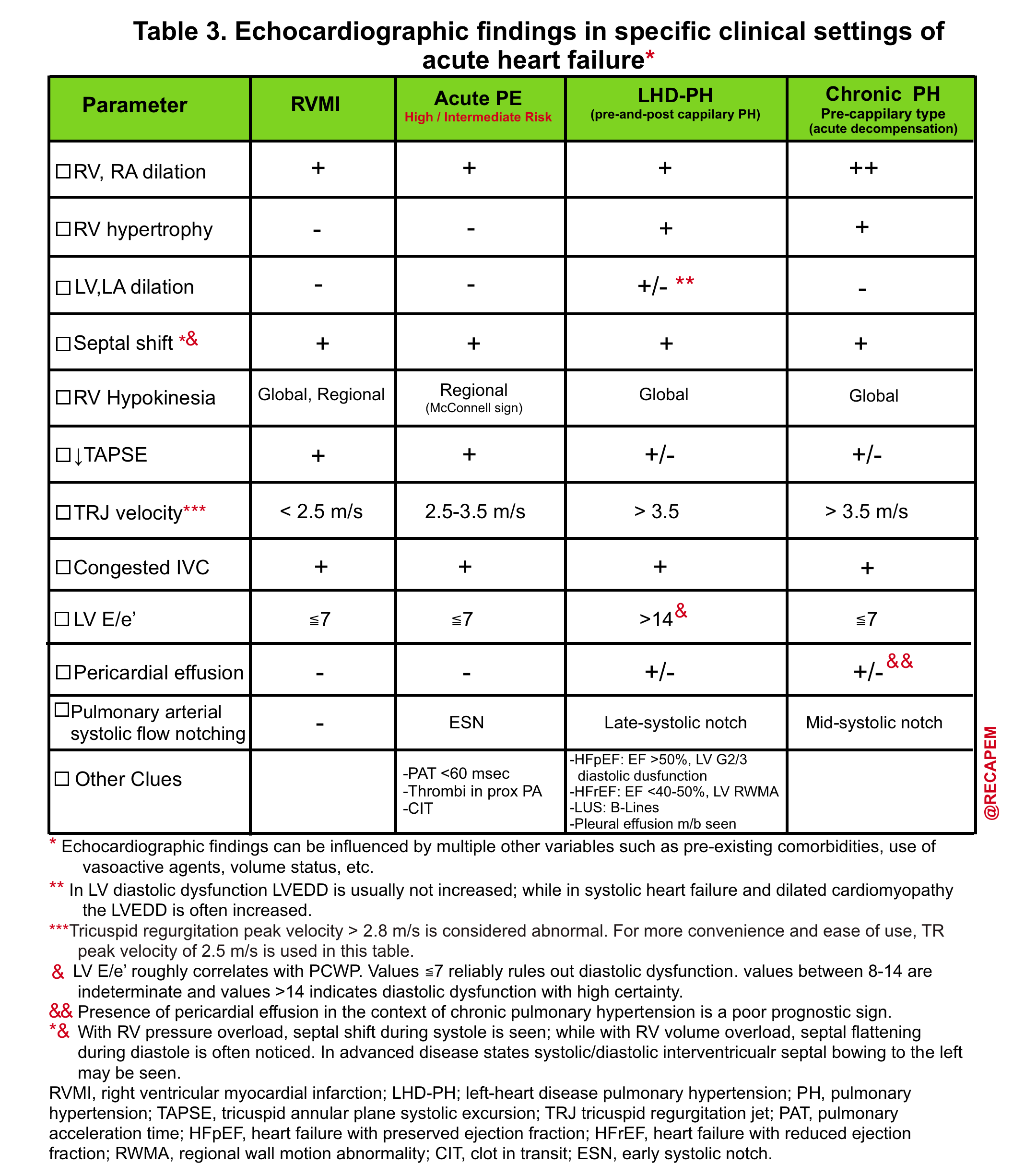

- Helpful echo findings in differentiating causes of acute right heart failure are summarized below.

Case scenario

In the following clinical cases, the focus of discussion is to frame the following fundamental questions:

- What clinical questions are you trying to answer with an echo?

- How do you interpret your findings in a clinical context?

A 40-year-old obese woman with a history of breast cancer presented to the hospital with watery diarrhea following her last chemo this morning. She looked pale and irritable.

HR135, BP 95/60, RR28, T37.3 C, SO2 90% room air, BS127. Subcostal echo showed hyperdynamic, underfilled LV. IVC measured 1.8 cm with >50% respiratory collapse. Other ultrasonographic findings were unremarkable, including a 3-point US examination of lower extremities, which showed no evidence of venous clot. She received a 2L crystalloid solution, an antibiotic, and supplemental oxygen via a non-rebreather mask and was monitored closely. After 1 hour, she complained of worsening shortness of breath. Upon further questioning, she opened up that her breathing difficulties started yesterday, which she had ignored. The subsequent US exams are shown below.

On the second exam, hyperdynamic, underfilled LV, RV enlargement (shown above), and IVC with <50% respiratory collapse were seen.

Hyperdynamic underfilled LV can be seen with two conditions:

- Right-sided low-pressure state with normal-sized RV and a normal IVC. The DDx might include hypovolemia and early sepsis among the list.

- Right-sided high-pressure state with dilated RV and IVC. The LV is hyperdynamic and underfilled since it is not receiving enough volume from the right side. The DDx would be hemodynamically significant PE, RVMI, and possibly other causes of acute RV failure.

Hyperdynamic LV should always be interpreted in the context of RV status.

Remember that in a patient with frank volume loss, a normal IVC is not reliable for ruling out massive PE. It is worth mentioning that the absence of DVT does not rule out the presence of PE, too. In a study using venography, DVT was found in 70% of patients with proven PE.25

In this patient, a CTPA study was performed and showed total occlusion of the right main pulmonary artery.

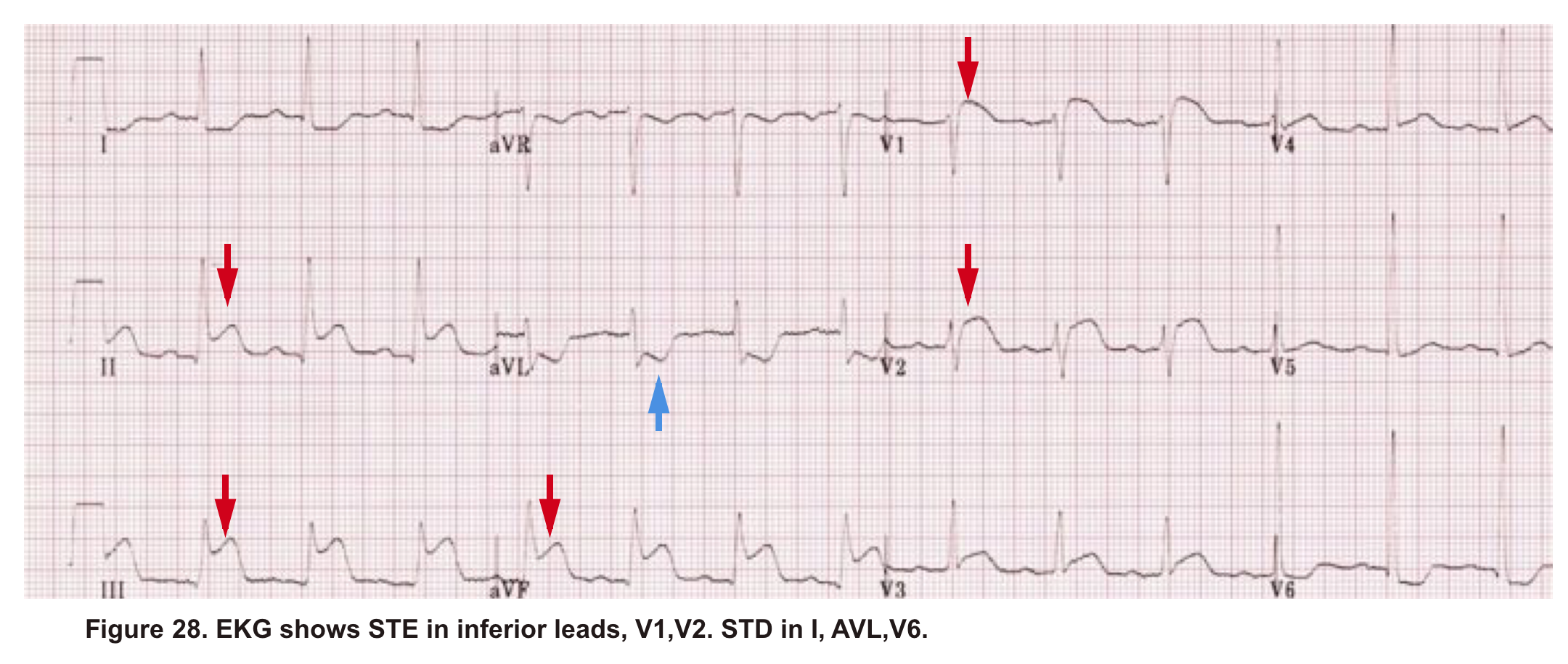

A 38-year-old woman with no significant past medical history presented to the hospital with ischemic chest pain and dyspnea. Upon entry, she looked pale, diaphoretic. BP100/80mm Hg, HR140, RR 25, SO2 91% room air. EKG showed STE in inferior and anteroseptal leads. Troponin was positive. Upon initial resuscitation (1L crystalloid fluid, anti-ischemic, antiplatelet meds), her hemodynamics deteriorated. She was taken for cardiac catheterization, which demonstrated no significant coronary arterial disease. After cardiac catheterization, TTE was performed (shown below).

Angiography has ruled out atherosclerotic coronary arterial lesions despite the presence of inferior and anteroseptal STE on EKG. Echo (A4C view) showed interventricular and interatrial septal shift to the left, as well as McConnell’s sign. IVC shows no respiratory collapse.

All these findings can be seen in both RV myocardial infarction (type I MI) as well as acute PE. Not to mention the fact that ‘TAPSE’ can be abnormal in both situations. Therefore, the above information is not helpful in differentiating between AMI (type I) and PE.

The primary problem in AMI (type I) is pump failure, while in acute massive PE, the pulmonary vascular resistance is increased.

The helpful echocardiographic parameter that can differentiate these two disease entities is PAP, which is increased in acute massive PE but is fairly low in RVMI.

In this case estimated PASP was 41 mmHg (shown below). A CTPA study was performed and showed bilateral total occlusion of the main pulmonary artery, and a decision was made for the administration of thrombolytic.

A 36-year-old man with no remarkable past medical history presented with flu-like symptoms and mild chest discomfort. He is tachypneic but not in respiratory distress. HR 90, BP 95/55, RR26, T38.5C, SO2 85% room air. EKG showed ‘incomplete RBBB’.

Physical exam was remarkable for central cyanosis, clubbing, and dry mucous membrane. No peripheral edema was detected. Lung US revealed A-profile. No evidence for DVT on the US exam of the lower extremities was found. The echo exam at A4C is shown below. The patient received supplemental oxygen and 500 cc of crystalloid solution.

The RA and RV obviously are enlarged with interatrial and interventricular septal flattening. On A4C TTE, an interatrial septal defect was noted, raising suspicion for ASD. This was confirmed on the subcostal view.

Color Doppler, as well as contrast study with saline injection, were performed to detect the shunt.

The right-to-left shunt was shown on the color Doppler. Following saline injection, complete opacification of RA and RV with early crossing bubbles into the LA and LV, consistent with an intracardiac shunt, was demonstrated.

The hemodynamic effects of ASD are primarily related to the direction and magnitude of shunting. In most patients, the greater compliance of the RV compared with the LV and the lower resistance of the pulmonary compared with the systemic circulation result in a net left-to-right shunt, leading to RV dilation. The pulmonary vasculature normally accommodates the increased volume of flow secondary to ASD without a significant increase in PA pressure. With continued RV volume overload and increased PA flow over time, some patients will develop pulmonary hypertension (PH). Development of PH is associated with right-to-left shunt as well as interventricular flattening during systole.26

Eisenmenger syndrome is the triad of congenital systemic-to-pulmonary communication, pulmonary arterial disease, and cyanosis. It implies that the development of pulmonary arterial disease is a consequence of increased pulmonary blood flow, and requires the exclusion of other causes of PH.27

In this case, CTPA was negative for pulmonary embolism.

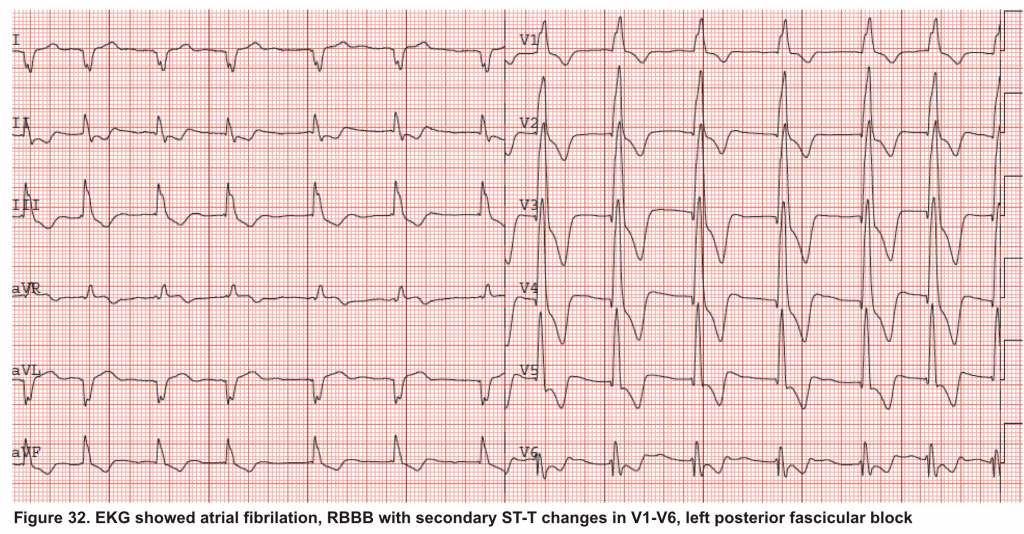

A 65-year-old man with a past medical history of HTN, COPD, and atrial fibrillation presented to the hospital with acute shortness of breath. He looked diaphoretic with respiratory discomfort. The initial set of vitals showed BP160/100, HR irregular, ranging from 70-90, RR 30, SO2 90% room air. EKG is shown below. While initial resuscitative measures were ongoing, bedside echocardiography was performed (shown below). RV free wall diastolic diameter in subcostal view read at 8 mm. IVC measured 23 mm with < 50% collapse with a sniff. US exam of the right lower extremity at the popliteal vein is shown below.

Is this clinical presentation and information obtained from bedside US suggestive of PE?

- The echo is remarkable for the enlarged RA, RV with the septal shift to the left, and severe TR. Pericardial effusion without diastolic chamber collapse is noticed as well. Echogenicity within the right popliteal vein is in favor of DVT.

- The past medical history, presence of RV-free wall hypertrophy, and a severe TR (4m/s) with an estimated PASP of about 74 mmHg are all indicative of the presence of chronic pulmonary hypertension. The presence of lower extremity DVT will increase the pretest probability for PE; however, none of the above findings are diagnostic for acute PE in this case.

- Acute decompensation of chronic pulmonary hypertension can occur due to multiple problems, as well as new-onset superimposing PE. Unfortunately, no bedside US findings are definitively diagnostic for PE in such cases, unless ‘CLOT IN TRANSIT’ is seen. In patients with acute decompensation of chronic pulmonary hypertension, CTPA or V/Q lung scan is diagnostic.

In this case, CTPA revealed no evidence of pulmonary embolism, and the patient was treated for acute decompensation of pulmonary hypertension and DVT.

💡Tip: As mentioned in Table 3, the presence of pericardial effusion in patients with chronic pulmonary hypertension carries a poor prognosis. 28

A 65-year-old woman was presented to the hospital with syncope. During the initial evaluation in the triage, she became unresponsive and pulseless.CPR immediately started and the patient was transferred to the resus bay. While the resuscitation was undergoing, her husband mentioned that she has a history of HTN, stroke (s/p 8 months), lower extremity DVT, and GI bleeding. The monitor showed rapid irregular narrow complex tachycardia, and Focused Echo (FE) showed no cardiac wall/valve motion (shown below).

Is RV dilation during cardiac arrest a specific finding for PE?

- Absolutely Not!

- Several recent studies have shown that relative or absolute RV enlargement during cardiac arrest can be seen with other possible causes, e.g., hypoxia, hyperkalemia, and primary arrhythmia(VF), and is not particularly associated with PE. These findings challenge the paradigm that RV dilatation on ultrasound during CPR is particularly associated with PE.31 32 33 34

Hemodynamic Support of RV Failure

- Identification and treatment of the underlying cause of RV failure, such as acute pulmonary embolism, acute decompensation of chronic pulmonary hypertension, and RV infarction, is the primary management strategy. Oftentimes, definitive diagnosis and implementation of specific treatment is time-consuming.

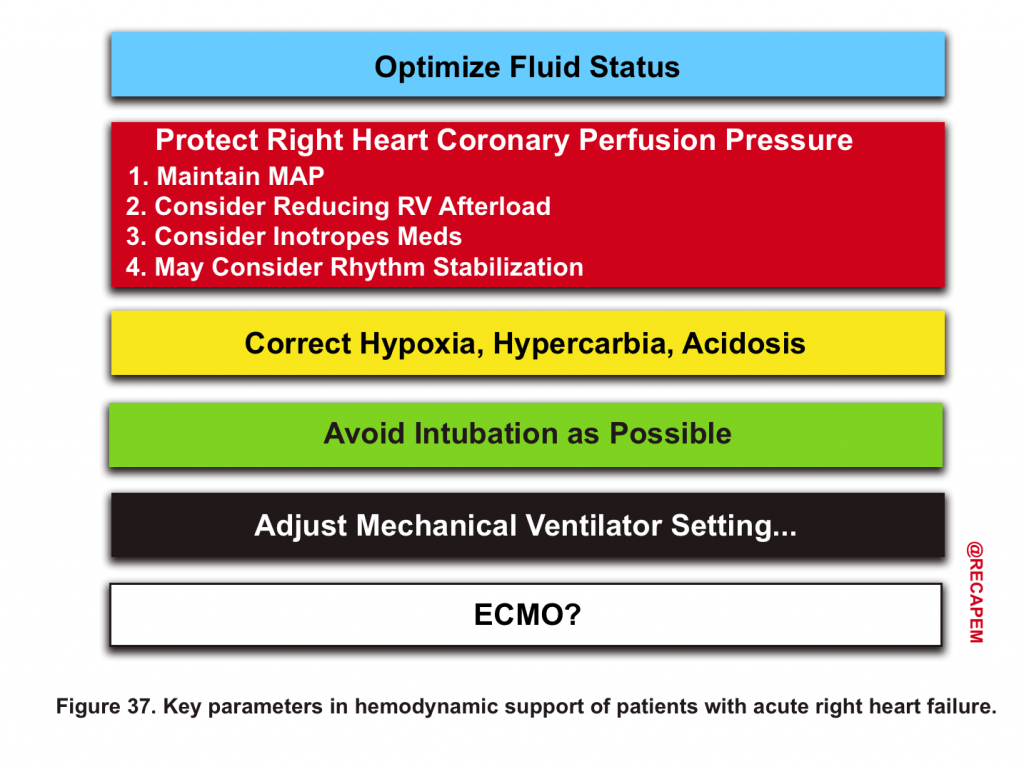

- Meanwhile, hemodynamic support is life-saving in the clinical care of these patients (Figure 37).14 16

Volume management

IV Fluid

- Despite that, patients with RV failure may be preload-dependent; vigorous fluid administration results in a leftward shift of the interventricular septum, ↓LV output, and hypotension through ventricular interdependence, especially in the setting of high intrathoracic pressure and pericardial disease.

- ⚠️Generally avoid fluid administration in acute RV failure unless a patient has frank volume loss, e.g., overt GIB, or in the setting of RVMI.16

- Is fluid administration safe in RV myocardial infarction (RVMI)?

- In RVMI, the primary problem is ↓RV contractility, but not the RV afterload (in contrast to PE, where RV afterload is the primary problem). Therefore, in RVMI, giving fluid will increase the pressure ahead and consequently increase RV cardiac output (RV behaving as a passive conduit).

- 👉IV fluid is often safe (if required) in RVMI.

Diuretics

- Patients with certain conditions, e.g., postcapillary pulmonary hypertension (chronic right heart failure due to left heart failure) with clinical signs of volume overload, may need diuretic treatment.14

- Treating left HF will reduce RV afterload by decreasing pulmonary artery pressures 35

- Ultrafiltration is an option for patients with refractory volume overload (diuretic-resistant).

Protect RV Perfusion

The right heart is perfused throughout the whole cardiac cycle. As explained in the context of the RV spiral of death (vicious cycle), the inciting events prime the right ventricle for the secondary ischemic insult. Even transient hypotension can be detrimental in such patients.

◾️Strategies that improve RV perfusion include

- Maintaining adequate MAP

- Inotropes

- Inhaled pulmonary vasodilators

- Correct hemodynamically significant brady-dysrhythmias and tachy-dysrhythmias.

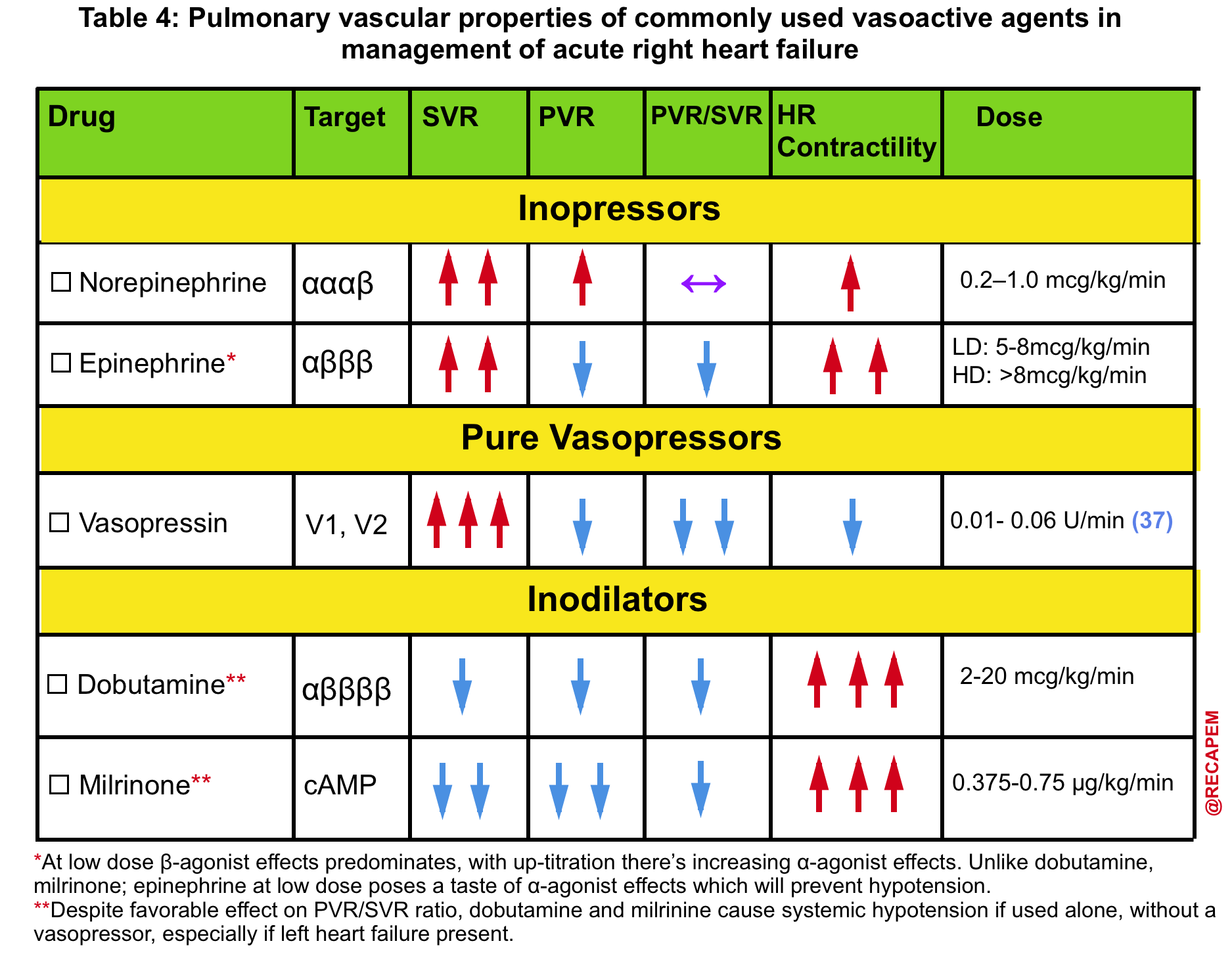

A. Maintaining MAP

- Hemodynamically unstable patients require vasopressors to keep their MAP within the safe range (60 to 65mm Hg).

- The agent of choice would be the one with optimal systemic vasopressor activity while having the least pulmonary vasoconstriction effect (↓PVR/SVR).13

- Norepinephrine, epinephrine36, and vasopressin administration are recommended.

- The pulmonary vascular properties of commonly used vasoactive agents are summarized in Table 4.

- ⚠️Avoid phenylephrine for its potential pulmonary vasoconstriction and dopamine for its arrhythmogenic properties.13

B. Inotropes

- If the primary problem is ↓contractility, e.g., RVMI, then administration of inotropes can improve contractility, reduce RVEDV, and cause perfusion improvement (Table 3 below).

C. Inhaled Pulmonary Vasodilators

- Strategies that decrease pulmonary vascular resistance (RV afterload) may include inhaled nitric oxide, epoprostenol, nitroglycerine 38, and milrinone 39

- Suggested dosage includes:

- Epoprostenol at 0.05mcg/kg/min

- Nitric Oxide at 20ppm

- Milrinone (1mg/ml), inhale 5mg over 15 minutes

- Nitroglycerin (1mg/ml), inhale 5mg over 15 minutes. More on this here.

D. Rhythm stabilization

- Patients with RV failure are susceptible to alterations in cardiac rhythm and ventricular synchrony.40 Clearly, hemodynamically significant bradycardias or tachyarrhythmias should be corrected.

- Supraventricular arrhythmias (especially atrial fibrillation) are more common than ventricular arrhythmias in PAH.

- Management of tachyarrhythmia is challenging. Most medications that are used for rate control (e.g., beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers) have the potential to drop the blood pressure.

- Digoxin may be a useful alternative for rate control.

- In patients with longstanding AF, cardioversion is often unsuccessful. Even after successful cardioversion, the atrial contraction (and cardiac output) is not improved.41

- Correction of the underlying conditions will often result in the elimination of AF.

Other considerations

◾️Correct Hypoxia, Hypercarbia, Acidosis

- Hypoxia causes pulmonary vasoconstriction(HPV), and this effect is potentiated in the presence of acidosis.42 43

- Adequate oxygenation to avoid HPV is of paramount importance.

- Administration of pulmonary vasodilators improves lung units with physiologic dead space, and therefore, elimination of carbon dioxide is augmented via improvement in alveolar ventilation.

⚠️Avoid Intubation as much as possible

- Patients with acute right heart failure most commonly succumb to death via cardiovascular collapse.

- Except for conditions with primarily involvement of the respiratory system, such as pneumonia, ARDS, intubating the patient is not the right decision.

- In extreme situations where intubation is required, minimizing the apeniec period and correcting the hypotension, acidosis, and hypoxia before proceeding to intubation are warranted. Hemodynamically neutral intubation (cardiostable intubation) is advised.

👉Most patients with right heart failure have tachypnea because of hemodynamic instability. They do not have primary respiratory problems, and as such, intubation will not fix their underlying condition.

- 💡The fact that a patient has severe tachypnea does not necessarily mean that intubation will resolve the problem.

◾️Mechanical Ventilator Setting

- Lung protective mechanical ventilator setting with considering low VT 4-6mL/kg/PBW, low peak pressure, Pplat ≦ 30 mmHg, minimal PEEP is recommended 14 (more on this here).

- Prone ventilation may unload the RV through effects on airway pressure and improved alveolar ventilation.45

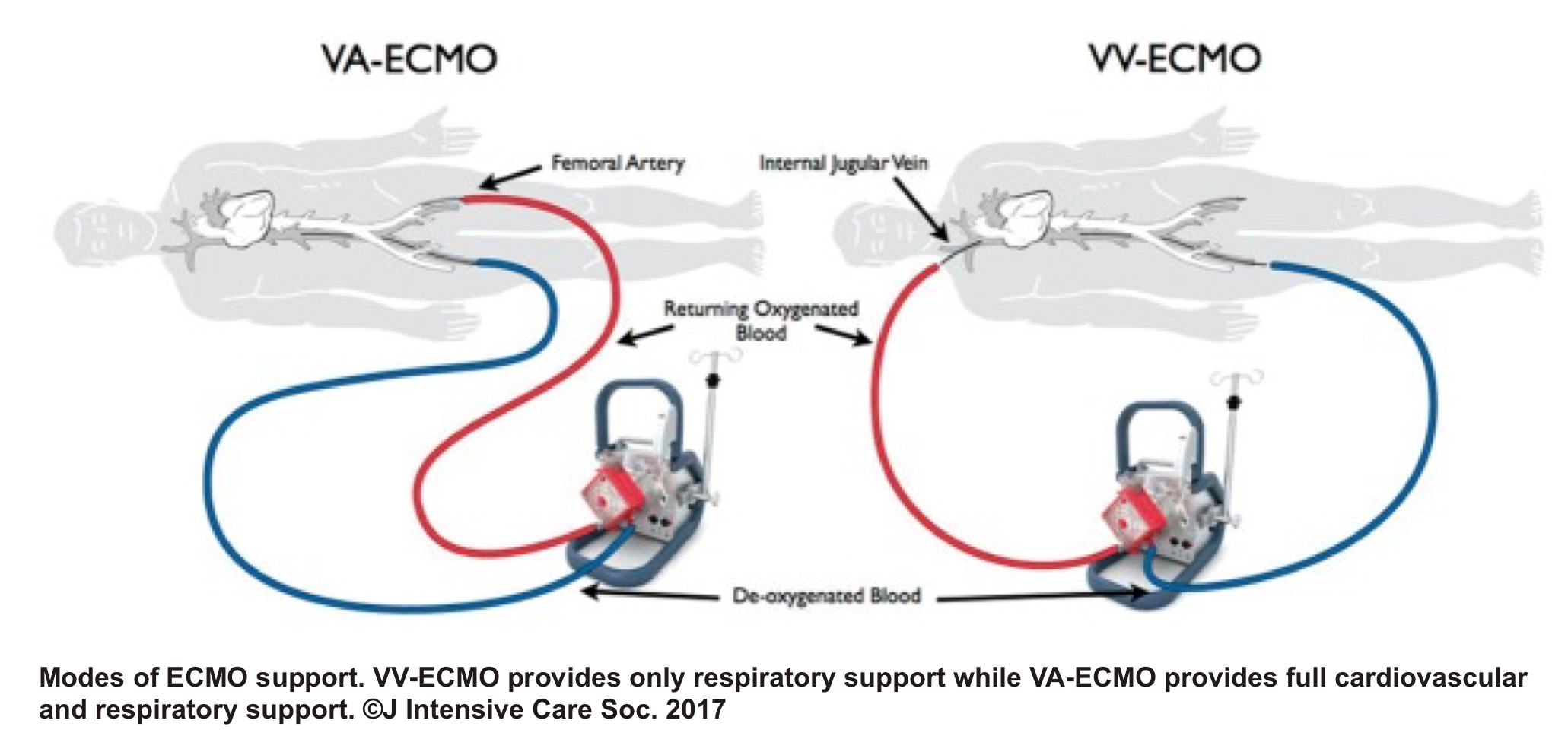

◾️VA ECMO

- Despite its limited availability, and lack of high-level evidence 46 47 regarding VA-ECMO for potential candidates with acute right heart failure, the mechanical circulatory support of the right ventricle may be considered in certain clinical situations such as RV myocardial infarction (MI), acute PE, following left ventricular assist device implantation, or primary graft failure after heart transplantation.48

RECAP

- Patients with acute right heart failure are critically ill and often have multiple comorbidities. Prompt diagnosis, hemodynamic support, and initiation of specific treatment are significantly important to keep your patient alive.

- Usually, there is a time lag between diagnosis and employment of specific treatment. The performance of bedside ultrasound is extremely helpful in making rapid diagnoses, risk-stratifying your patients, and guiding therapeutic regimens.

- The right heart structure and physiology are uniquely different from the left heart. The medications that are used for left heart failure often do not work for right heart failure. Understanding the right heart physiology and pathogenesis of RV failure makes this distinction clearer.

- The vicious cycle of RV failure makes it unforgiving for any misdiagnosis and mismanagement.

- Except for certain diseases, such as tamponade, for which pericardiocentesis may rapidly fix it, there are no such rapidly fixable treatments for almost all other causes of right heart failure. Appropriate hemodynamic support works as a bridge to the employment of specific treatments and the onset of their therapeutic effects. During this interim period, the following steps are life-saving and can improve RV performance:

-

- Interventions that improve RV perfusion, such as increasing MAP (if indicated) by systemic vasopressors, reducing PVR by inhaled pulmonary vasodilator medications, and augmenting RV contractility by inotropes (if indicated).

- Correcting other factors that potentially cause pulmonary vasoconstriction, such as hypoxia, hypercarbia, and acidosis.

- Perform bedside US to evaluate the volume status and optimize it accordingly. In a questionable situation, err on the side of keeping your patient dry.

- Correct hypotension, hypoxia, and acidosis before ever trying to intubate your patients, and Be Prepared. Hemodynamically neutral intubation and minimizing the apneic period are recommended.

- Be cautious of the deleterious effects of mechanical ventilation on the RV performance and employ strategies to minimize these adverse effects by using a low tidal volume, PEEP, and keeping Pplat < 30 mmHg.

Going further

- RV failure with Sara Crager (EMCrit)

- Pulmonary Hypertension and RV failure with Susan Wilcox(EMCrit)

- Eight pearls for the crashing patient with massive PE (PulmCrit)

- Right Ventricular failure due to pulmonary hypertension (IBCC)

- Right heart strain (Radiopaedia)

- Right heart strain (J Avila)

Appendix

Recommended conventional echocardiographic measures for the evaluation of right heart structures and function.

Media

References

1. Voelkel NF, Quaife RA, Leinwand LA, et al. Right ventricular function and failure: report of a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group on cellular and molecular mechanisms of right heart failure. Circulation. 2006;114(17):1883-1891. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.632208

2. Sheehan F, Redington A. The right ventricle: anatomy, physiology and clinical imaging. Heart. 2008;94(11):1510-1515. doi:10.1136/hrt.2007.132779

3. Foale, R et al. “Echocardiographic measurement of the normal adult right ventricle.” British heart journal vol. 56,1 (1986): 33-44. doi:10.1136/hrt.56.1.33

4. Haddad F, Hunt SA, Rosenthal DN, Murphy DJ. Right ventricular function in cardiovascular disease, part I: Anatomy, physiology, aging, and functional assessment of the right ventricle. Circulation. 2008;117(11):1436-1448. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.653576

5.Kim MJ, Jung HO. Anatomic variants mimicking pathology on echocardiography: differential diagnosis. J Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2013;21(3):103-112. doi:10.4250/jcu.2013.21.3.103

6. Ho SY, Nihoyannopoulos P. Anatomy, echocardiography, and normal right ventricular dimensions. Heart. 2006;92 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):i2-i13. doi:10.1136/hrt.2005.077875

7. Mehra MR, Park MH, Landzberg MJ, Lala A, Waxman AB; International Right Heart Failure Foundation Scientific Working Group. Right heart failure: toward a common language. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33(2):123-126. doi:10.1016/j.healun.2013.10.015

8.Haddad F, Doyle R, Murphy DJ, Hunt SA. Right ventricular function in cardiovascular disease, part II: pathophysiology, clinical importance, and management of right ventricular failure. Circulation. 2008;117(13):1717-1731. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.653584

9.Diebel LN, Wilson RF, Tagett MG, Kline RA. End-diastolic volume. A better indicator of preload in the critically ill. Arch Surg. 1992;127(7):817-822. doi:10.1001/archsurg.1992.01420070081015

10. Messerli FH, Rimoldi SF, Bangalore S. The Transition From Hypertension to Heart Failure: Contemporary Update [published correction appears in JACC Heart Fail. 2017 Dec;5(12 ):948]. JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5(8):543-551. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2017.04.012

11. Vonk-Noordegraaf A, Westerhof N. Describing right ventricular function. Eur Respir J. 2013;41(6):1419-1423. doi:10.1183/09031936.00160712

12.Konstam MA, Kiernan MS, Bernstein D, et al. Evaluation and Management of Right-Sided Heart Failure: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137(20):e578-e622. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000560

13. Dell’Italia LJ. The right ventricle: anatomy, physiology, and clinical importance. Curr Probl Cardiol. 1991;16(10):653-720. doi:10.1016/0146-2806(91)90009-y

14. Price, L.C., Wort, S.J., Finney, S.J. et al. Pulmonary vascular and right ventricular dysfunction in adult critical care: current and emerging options for management: a systematic literature review. Crit Care 14, R169 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc9264

15. Lahm T, McCaslin CA, Wozniak TC, et al. Medical and surgical treatment of acute right ventricular failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(18):1435-1446. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.046

16. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC [published correction appears in Eur Heart J. 2016 Dec 30;:]. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(27):2129-2200. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128

17. Rudski LG, Lai WW, Afilalo J, et al. Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography endorsed by the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23(7):685-788. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2010.05.010

18. DiLorenzo MP, Bhatt SM, Mercer-Rosa L. How best to assess right ventricular function by echocardiography. Cardiol Young. 2015;25(8):1473-1481. doi:10.1017/S1047951115002255

19. Jefkins M, Chan B. Hepatic and portal vein Dopplers in the clinical management of patients with right-sided heart failure: two case reports. Ultrasound J. 2019;11(1):30. Published 2019 Nov 12. doi:10.1186/s13089-019-0146-3

20. Parasuraman S, Walker S, Loudon BL, et al. Assessment of pulmonary artery pressure by echocardiography-A comprehensive review. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2016;12:45-51. Published 2016 Jul 4. doi:10.1016/j.ijcha.2016.05.011

21. Schneider M, Binder T. Echocardiographic evaluation of the right heart. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2018;130(13-14):413-420. doi:10.1007/s00508-018-1330-3

22. Roberts JD, Forfia PR. Diagnosis and assessment of pulmonary vascular disease by Doppler echocardiography. Pulm Circ. 2011;1(2):160-181. doi:10.4103/2045-8932.83446

23. Afonso L, Sood A, Akintoye E, et al. A Doppler Echocardiographic Pulmonary Flow Marker of Massive or Submassive Acute Pulmonary Embolism. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2019;32(7):799-806. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2019.03.004

24. Orde S, Slama M, Hilton A, Yastrebov K, McLean A. Pearls and pitfalls in comprehensive critical care echocardiography. Crit Care. 2017;21(1):279. Published 2017 Nov 17. doi:10.1186/s13054-017-1866-z

25. Silvestry FE, Cohen MS, Armsby LB, et al. Guidelines for the Echocardiographic Assessment of Atrial Septal Defect and Patent Foramen Ovale: From the American Society of Echocardiography and Society for Cardiac Angiography and Interventions. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28(8):910-958. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2015.05.015

26. Konstantinides SV, Meyer G, Becattini C, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Respir J. 2019;54(3):1901647. Published 2019 Oct 9. doi:10.1183/13993003.01647-2019

27. Aagaard R, Caap P, Hansson NC, Bøtker MT, Granfeldt A, Løfgren B. Detection of Pulmonary Embolism During Cardiac Arrest-Ultrasonographic Findings Should Be Interpreted With Caution. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(7):e695-e702. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000002334

28. Aagaard R, Granfeldt A, Bøtker MT, Mygind-Klausen T, Kirkegaard H, Løfgren B. The Right Ventricle Is Dilated During Resuscitation From Cardiac Arrest Caused by Hypovolemia: A Porcine Ultrasound Study. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(9):e963-e970. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000002464

29. Sørensen AH, Wemmelund KB, Møller-Helgestad OK, Sloth E, Juhl-Olsen P. Asphyxia causes ultrasonographic D-shaping of the left ventricle–an experimental porcine study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2016;60(2):203-212. doi:10.1111/aas.12606

30. Berg RA, Sorrell VL, Kern KB, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging during untreated ventricular fibrillation reveals prompt right ventricular overdistention without left ventricular volume loss. Circulation. 2005;111(9):1136-1140. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000157147.26869.31

31. Vonk Noordegraaf A, Westerhof BE, Westerhof N. The Relationship Between the Right Ventricle and its Load in Pulmonary Hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(2):236-243. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.047

32. Yurtseven N, Karaca P, Kaplan M, et al. Effect of nitroglycerin inhalation on patients with pulmonary hypertension undergoing mitral valve replacement surgery. Anesthesiology. 2003;99(4):855-858. doi:10.1097/00000542-200310000-00017

33. Gordon AC, Mason AJ, Thirunavukkarasu N, et al. Effect of Early Vasopressin vs Norepinephrine on Kidney Failure in Patients With Septic Shock: The VANISH Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;316(5):509-518. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.10485

34. Boulain T, Lanotte R, Legras A, Perrotin D. Efficacy of epinephrine therapy in shock complicating pulmonary embolism. Chest. 1993;104(1):300-302. doi:10.1378/chest.104.1.300

35. Sablotzki A, Starzmann W, Scheubel R, Grond S, Czeslick EG. Selective pulmonary vasodilation with inhaled aerosolized milrinone in heart transplant candidates. Can J Anaesth. 2005;52(10):1076-1082. doi:10.1007/BF03021608

36. Goldstein JA, Harada A, Yagi Y, Barzilai B, Cox JL. Hemodynamic importance of systolic ventricular interaction, augmented right atrial contractility and atrioventricular synchrony in acute right ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;16(1):181-189

37. Upshaw CB Jr. Hemodynamic changes after cardioversion of chronic atrial fibrillation. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(10):1070-1076

38. Stengl M, Ledvinova L, Chvojka J, et al. Effects of clinically relevant acute hypercapnic and metabolic acidosis on the cardiovascular system: an experimental porcine study. Crit Care. 2013;17(6):R303. Published 2013 Dec 30. doi:10.1186/cc13173

39. Dunham-Snary KJ, Wu D, Sykes EA, et al. Hypoxic Pulmonary Vasoconstriction: From Molecular Mechanisms to Medicine. Chest. 2017;151(1):181-192. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2016.09.001

40. Webb ST, Arrowsmith JE. Acute hemodynamic collapse after induction of general anesthesia for emergent pulmonary embolectomy. Anesth Analg. 2007;104(3):742. doi:10.1213/01.ane.0000253910.41044.56

41. Vieillard-Baron A, Charron C, Caille V, Belliard G, Page B, Jardin F. Prone positioning unloads the right ventricle in severe ARDS. Chest. 2007;132(5):1440-1446. doi:10.1378/chest.07-1013

42. Pasrija C, Kronfli A, George P, et al. Utilization of Veno-Arterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Massive Pulmonary Embolism. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;105(2):498-504. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.08.033

43. George B, Paranzino M, Omar HR, et al. A retrospective comparison of survivors and non-survivors of massive pulmonary embolism receiving veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support. Resuscitation. 2018;122:1-5. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2017.11.034

44. de Asua I, Rosenberg A. On the right side of the heart: Medical and mechanical support of the failing right ventricle. J Intensive Care Soc. 2017;18(2):113-120. doi:10.1177/1751143716684357

Add comment