Jan, 25, 2022 via Shahriar Lahouti.

CONTENTS

- Introduction with a case

- Preface

- Mean arterial pressure

- Hypertension- definition

- Pathophysiology

- Approach to hypertensive emergencies

- Management

- RECAP

- Going further

- References

Introduction- Case

A 68-year-old woman with known hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea comes to the ED and reports headaches and blurred vision for the past 2 days. Her prescribed medications include amlodipine, hydrochlorothiazide, telmisartan, and bisoprolol. She uses CPAP for sleep breathing disorder but she acknowledges poor adherence and has not taken any of the drugs in approximately 1 week. On examination, she is confused but comfortable. The average of multiple blood pressure measurements is 231/137 mmHg, and the heart rate is 68 bpm, oxygen saturation is 96% RA. The electrocardiogram shows left ventricular hypertrophy. POCUS and other laboratory tests are unremarkable. Emergency CT of the head shows heterogeneous hypoattenuation of subcortical white matter in the posterior parieto-occipital regions bilaterally but no hemorrhage or infarction. How would you further evaluate and treat this patient?

Preface

Most patients with significantly elevated blood pressure have no acute, end-organ injury. Various retrospective reviews from adult emergency departments found that hypertensive emergencies account for less than 1 percent of all visits 1 with an estimated population incidence (based upon large claims databases) of one to two cases per million per year.

The most common mistake in practice is overdiagnosis of hypertensive emergency among patients with scary high blood pressure but no target organ damage. In this post hypertensive emergency is reviewed with more focus on hypertensive emergency without a known cause.

Mean arterial blood pressure (MAP)

MAP is the average blood pressure in a subject during the cardiac cycle. It represents the best single index of organ perfusion status and more closely correlates with risk of development of target organ damage. MAP is the preferred measurement of blood pressure for the following reasons:

- MAP is what the automated BP cuff is actually measuring: Automated oscillometric BP cuffs measure the MAP directly (whereas the systolic and diastolic BP are estimated using proprietary algorithms). This could make the MAP the most accurate measurement.

- While SBP is the focus of attention, the risk of hypertensive emergency seems overall to be more closely related to the diastolic pressure than the systolic pressure.

- By and large, MAP is probably the single parameter that is most closely related to the risk of hypertensive emergency.

- MAP is also the preferred BP index in therapy. The dosing of any antihypertensive drug can be more easily titrated against a single variable. Trying to titrate an antihypertensive infusion against systolic and diastolic blood pressure simultaneously is often impossible and confusing (for example, what happens if the systolic target is reached but not the diastolic!)

Definitions

Definition of hypertension (HTN)

- The Joint National Committee 8 guidelines retained the same definitions of normal BP as the Joint National Committee 7 guidelines, with an average SBP <120 mm Hg and an average DBP <80 mm Hg. Hypertension is defined as office SBP values ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic BP (DBP) values ≥ 90 mmHg.

- It should be noted that the number cutoffs (in the classification of BP and grading of HTN) are arbitrary and based on consensus opinion from the Joint National Committee 8 and thus should be used in the context of the specific clinical scenario (i.e. not all patients with markedly elevated BP have a hypertensive emergency).

Hypertensive emergency: It should be considered in any patient presenting with severely elevated BP (typically >180/120 mm Hg) and the presence of ongoing target organ damage.

- Keep in mind that normotensive individuals may develop hypertensive emergency at substantially lower BPs, in part because the adaptive vascular changes that protect organs from changes in BP have not developed 2. Alternatively, patients with chronic hypertension may have extremely elevated BP without hypertensive emergency.

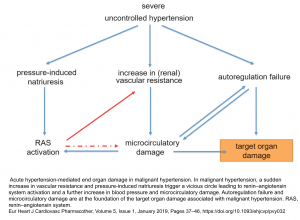

Pathophysiology

Chronic uncontrolled hypertension leads to progressive microvascular damage. This will cause a vicious spiral that perpetuates target organ damage (figure below) 3.

- The core of this spiral is that hypertension causes microcirculatory damage that impairs renal perfusion, leading to activation of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS). RAS activation, in turn, causes vasoconstriction, which leads to worsening hypertension.

- Pressure-induced natriuresis further contributes to the contraction of blood volume and activation of the renin–angiotensin system.

- Microvascular damage and autoregulation failure are at the foundation of the target organ damage associated with malignant hypertension and result in hypertensive retinopathy, TMA, and encephalopathy, complications that are not observed in patients with chronic uncontrolled hypertension.

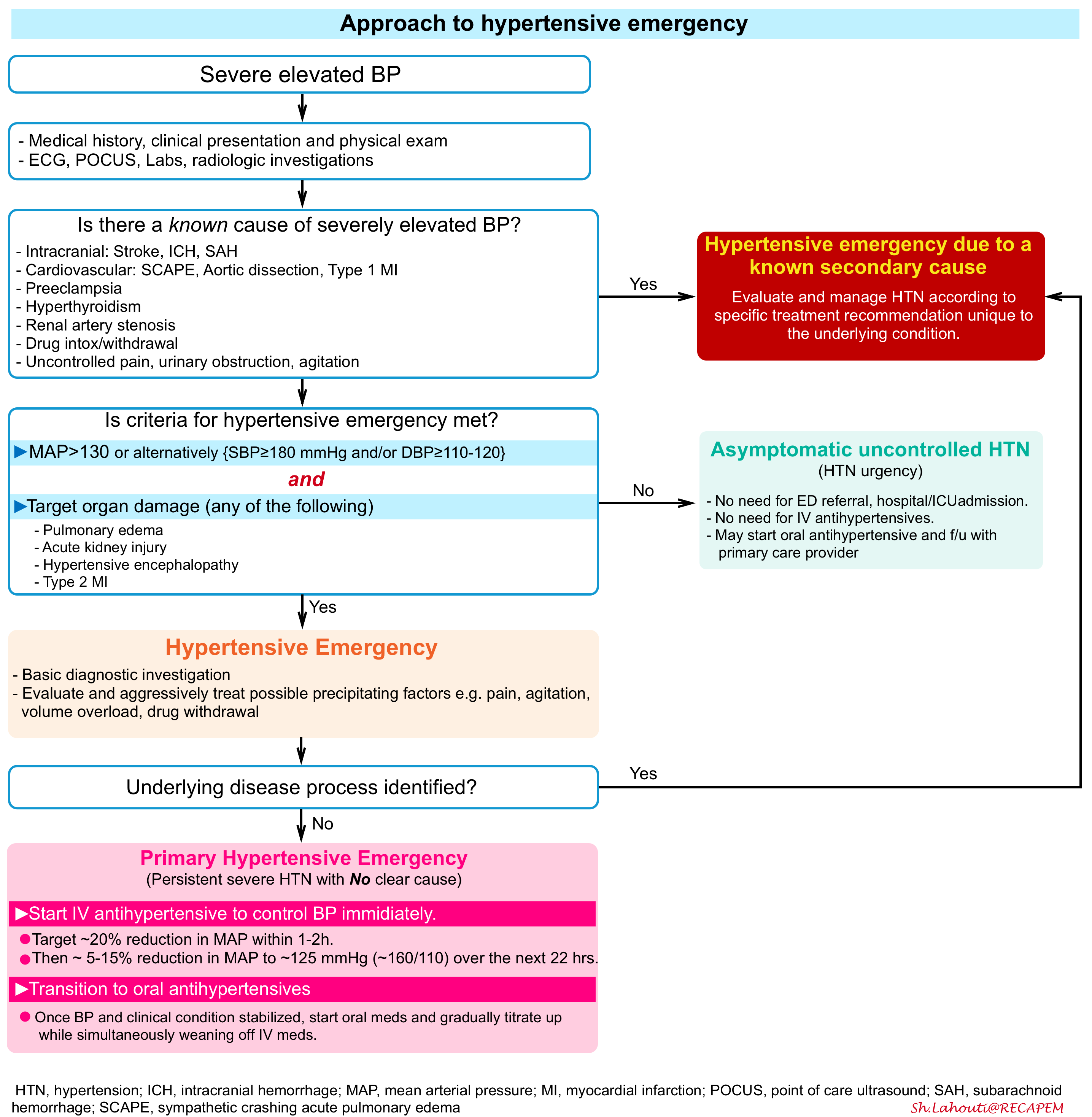

Approach to hypertensive emergencies

Algorithm: An overview of the approach to hypertensive emergency is shown below.

Secondary hypertensive emergencies

Severely elevated BP can be the result of some other primary process 4. In most cases, the primary process will be more obvious clinically, dominating the initial clinical presentation (e.g. aortic dissection, sympathetic crashing acute pulmonary edema, etc.). Prompt management of BP is recommended, however treatment will vary widely, depending on the specific context. Some clinically common examples include 5:

- Aortic dissection

- SCAPE (sympathetic crashing acute pulmonary edema)

- Intracranial: Stroke, ICH, SAH

- Preeclampsia

- Endocrinopathy (e.g. pheochromocytoma, hyperthyroidism).

- Renal (scleroderma renal crisis, acute glomerulonephritis, renal artery stenosis).

- Drug withdrawal/intoxication: Withdrawal (e.g. from alcohol or benzodiazepines) / Sympathomimetic drugs intoxication e.g. cocaine or methamphetamines.

- Other medications (e.g. cyclosporine, tacrolimus, erythropoietin, steroid, NSAIDs, anti-angiogenic drugs).

- Pain, urinary obstruction, anxiety.

- Volume overload

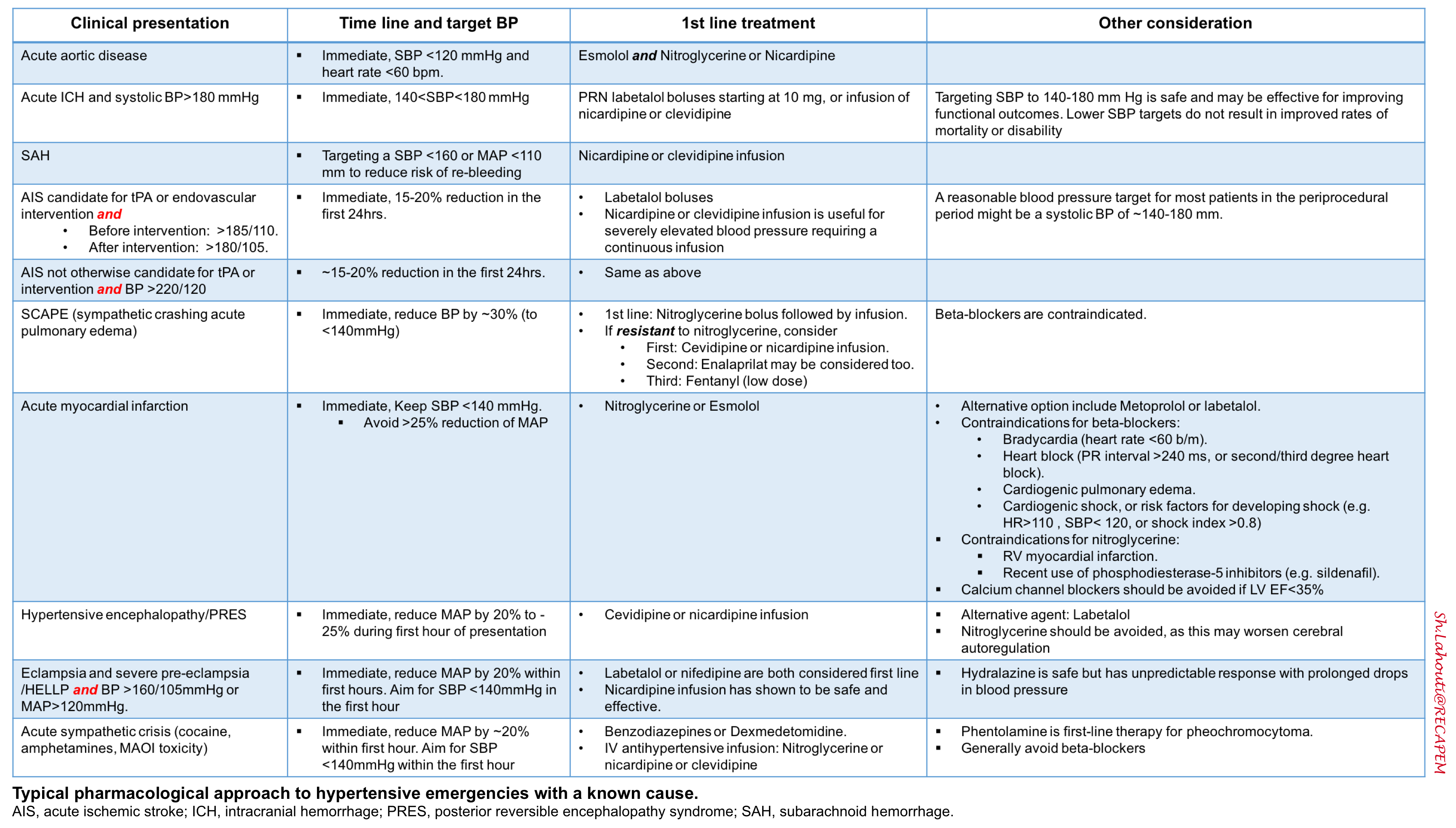

🚩In this post, the discussion is centered on primary hypertensive emergency. For the pharmacologic approach to hypertensive emergencies with a known cause see the following table.

Diagnostic criteria

Hypertensive emergency 3

- Severe hypertension

- Usually, a MAP of at least >135 mm is needed to cause a hypertensive emergency (SBP ≥180 mmHg and/or DBP ≥120 mmHg).

- However these numbers may vary considerably depending on the patient’s baseline BP. The relative change in blood pressure from baseline is more important than its absolute value.

- Ongoing target organ damage

- Pulmonary edema

- Acute kidney injury (often with microscopic hematuria)

- Hypertensive encephalopathy (e.g. delirium, visual disturbance, seizure).

- Myocardial ischemia (type-II myocardial ischemia). This should be a true myocardial infarction, not solely an elevated troponin.

Hypertensive urgency

This is a term that has been used to refer to patients with severely elevated BP (>180/120) who do not have target organ damage. However, this is a misnomer because there is no “urgent” need to reduce the BP 6, and:

- There is NO need for referral to the emergency department.

- There is NO need for hospital admission.

- There is NO need for ICU admission.

It would probably be ideal to eliminate the term “hypertensive urgency” and replace it with the term “asymptomatic uncontrolled hypertension” (which might discourage over-reacting to this condition) 7.

If a patient with hypertensive urgency is encountered in the outpatient context, it might be reasonable to start them on a low dose of a chronic oral antihypertensive agent with a relatively benign side-effect profile (e.g. amlodipine). It might also be reasonable to arrange close follow-up with their primary care provider for the management of their blood pressure. Obtaining adequate follow-up and ambulatory blood pressure measurement is probably more important than immediate patient management. This is not a critical care topic, so it’s beyond the scope of this book.

Evaluation

- Repeat blood pressure measurement

- History

- Baseline BPs

- History of hypertension?

- Antihypertensive regimen?

- Compliance with regimen?

- Sleep-disordered breathing?

- Nonadherence with CPAP or BiPAP therapy?

- Any prior episodes of hypertensive emergency?

- Illicit drug use?

- Symptoms

- Chest discomfort

- Dyspnea

- Delirium or depressed level of consciousness, visual disturbance, seizure, vomiting, and headache are found in patients with hypertensive encephalopathy or posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES).

- Remember that Epistaxis, proteinuria, chronic renal failure, and headache Do NOT qualify as target organ damage 7.

- POCUS

- Evidence of aortic dissection?

- Pulmonary edema on lung ultrasonography?

- IVC: Volume status?

- Optic nerve sheath diameter: Increased optic nerve sheath diameter on ultrasound might support the diagnosis of hypertensive encephalopathy with increased intracranial pressure.

- Renal ultrasound (postrenal obstruction, kidney size, left to right difference)

- ECG

- Labs

- Basic labs (chemistries, CBC, coagulation studies).

- PBS: blood smear may be required to search for microangiopathic anemia (schictocytes).

- Troponin (only if ECG/clinical evidence to support MI).

- Urinalysis: May reveal proteinuria or hematuria in patients with renal damage

- Urine toxicology screen may be considered.

- Pregnancy evaluation as appropriate

- Non-contrast head CT: If the presentation is worrisome for possible intracranial hemorrhage.

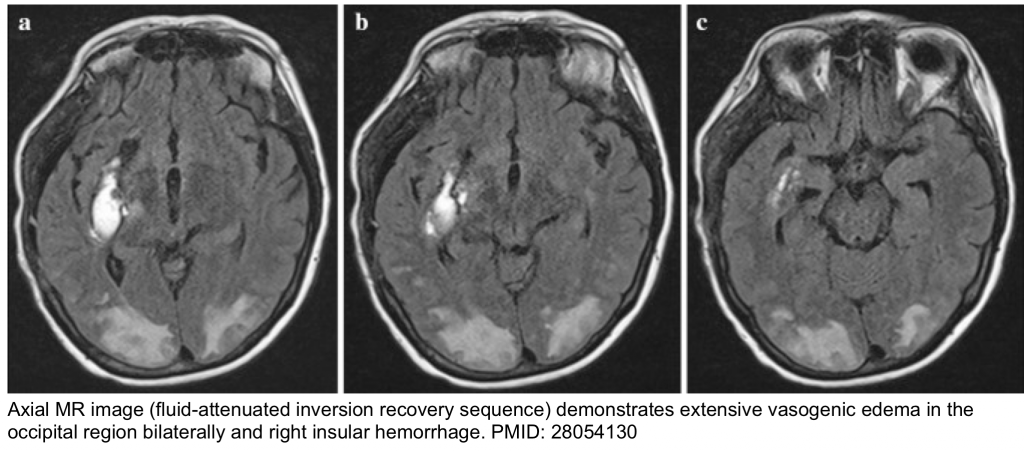

- Brain MRI: T2/FLAIR MRI is often required to confirm a clinical diagnosis of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES). Vasogenic edema is invariably seen on MRI and appears as hyperintensity on T2/FLAIR (figure below).

- CT-angiography of thorax and abdomen (If acute aortic disease suspected)

Management

Initial measures

Management begins with appropriate monitoring including serial automated BP assessments, and cardiac telemetry. Ensure a patent airway, and supplement oxygen as needed. Obtain bilateral, large-bore (i.e. 18-20 g) peripheral venous access.

Arterial line: Indications for an arterial line might include:

- Very labile blood pressure.

- Profound hypertension (too high to be real?).

- Clinical deterioration despite noninvasive management.

Initial diagnostic/therapeutic measures

- Before initiation of antihypertensives, consider some simple interventions that may be highly effective in reducing blood pressure. Interventions that may rapidly reduce the blood pressure:

-

- Pain: Treat with appropriate analgesia.

- Agitation: Treat with antipsychotics, dexmedetomidine, or benzodiazepines.

- Volume overload: Treat with diuresis or dialysis.

- Alcohol withdrawal: Phenobarbital.

- Urinary retention: Foley catheter.

Antihypertensive treatment

Basic principles

- In general; Continuous infusions are used for drugs with a short half-life (e.g. Nitroglycerine). The short half-life means that the drug needs to be infused continuously. It also makes the drug easily titratable.

- Intermittent boluses are used for drugs with longer half-lives (most drugs).

- Anti-hypertensive drugs can be classified into roughly three groups

- Truly titratable agents: Duration of action is less than 30min. These drugs must be given as a continuous infusion and these are very easily titratable.

- Examples: Nitroglycerine, esmolol, clevidipine

- Quasi-titratable agents: Duration of action is <1-2 hours. The drug is generally given as a continuous infusion, but it’s a bit sluggish to titrate.

- Examples: Nicardipine, diltiazem

- Bolus agents: Duration of action is >1-2 hours. The easiest way to give the drug is as intermittent bolus doses. If an infusion is used, it will tend to accumulate and be rather difficult to titrate.

- Examples: Labetalol, and metoprolol.

- Truly titratable agents: Duration of action is less than 30min. These drugs must be given as a continuous infusion and these are very easily titratable.

Target BP

- The initial goal is to decrease the MAP by ~20% within 1-2 hours 9.

- If this reduction is tolerated, then decrease the MAP by ~5-15% to ~125 mmHg (~160/110) over the next 22-23 hours.

- The blood pressure may subsequently be gradually decreased further over a period of days, as clinically tolerated.

- These general recommendations may not hold for every patient. Consider what the patient’s baseline pressure is, and how rapid the increase in pressure was.

- For a patient with chronic hypertension, a more gradual approach to lowering the BP may be wise.

- For a patient with very acute development of hypertension (e.g. due to an acute sympathomimetic drugs intoxication), a more rapid reduction of BP may be reasonable.

Troubleshooting: If BP drops following IV antihypertensive medications.

- Pathophysiologic background

- Patients have excessive vasoconstriction, which is driving their hypertension.

- Most hypertensive emergency patients are volume-depleted due to the phenomenon of pressure natriuresis.

- When treated with vasodilation, these patients may develop hypotension (due to unmasking of their hypovolemia). As such, IV fluid administration should be considered, which may prevent iatrogenic hypotension when antihypertensives are initiated.

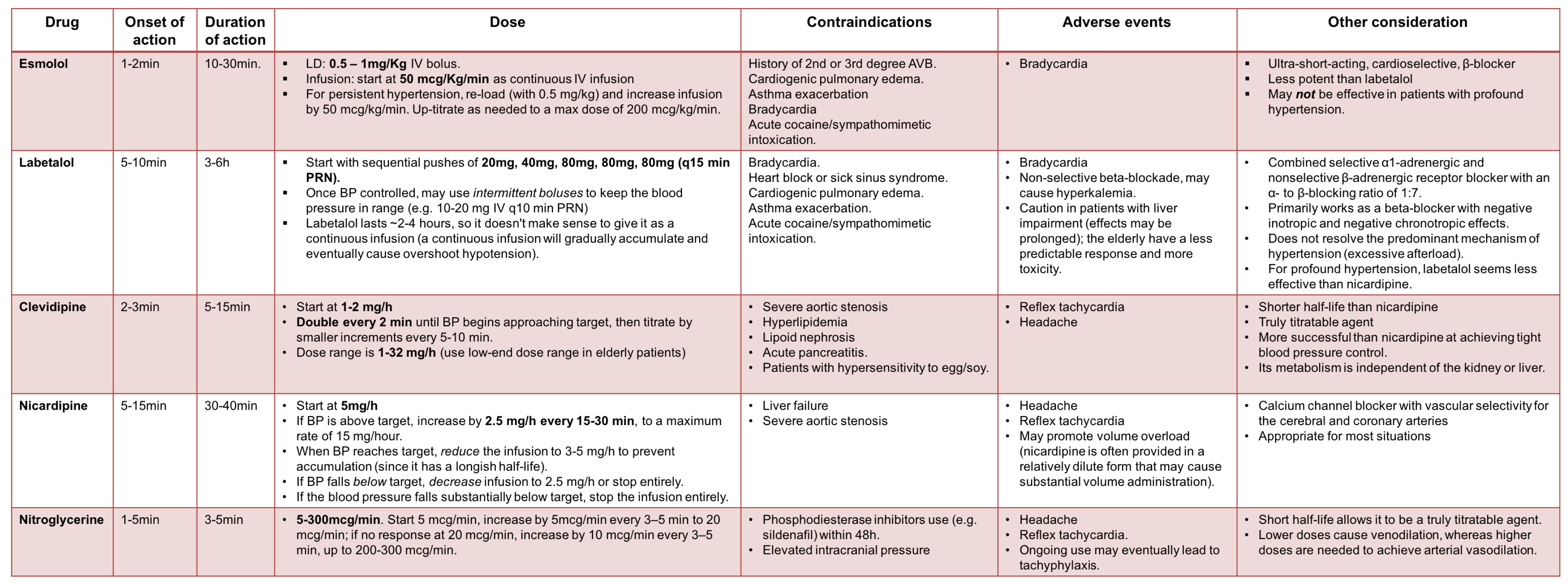

IV Antihypertensive medications 6, 8

⚠️The following agents are better to be avoided for hypertensive emergencies:

- Nitroprusside

- Can increase the intracranial pressure

- Can cause cyanide toxicity and lactic acidosis

- Tends to cause wide swings in the BP, therefore an arterial line should be inserted to allow for adequate monitoring of these BP swings.

- Hydralazine.

- Effect is unpredictable

- Impossible to titrate

- In most situations, another agent will be equally effective and safer (one potential exception is preeclampsia with refractory hypertension).

Transition to oral antihypertensive medication

After BP has been controlled for 12-24 hours, oral antihypertensive agents may be initiated while the patient is weaned off IV agents.

- Start oral antihypertensives after the patient has stabilized and improved on IV antihypertensives for several hours.

- Oral antihypertensives may be gradually up-titrated, with simultaneous weaning off IV antihypertensives.

- The key concern with oral antihypertensive agents is how rapidly they take effect. As in any other situation where you’re up-titrating medications, it’s important to allow one dose of medication to take effect before you escalate the dose.

- If doses are escalated before the last dose has taken effect, this may eventually lead to an excessive drop in blood pressure.

- The ideal oral antihypertensive will take effect in under ~2 hours. This allows for a fairly prompt up-titration of oral doses, which allows rapid weaning of the IV antihypertensive agent

- ⚠️Agent to avoid

- Amlodipine takes forever to work and has no role in the management of hypertensive emergencies.

- Metoprolol drops heart rate but is relatively ineffective for controlling blood pressure.

- Carvedilol is an alpha/beta blocker, similar to labetalol. It’s a reasonable choice, but with a half-life of 6-10 hours, it takes a few doses to reach a steady state. This precludes the ability to perform rapid oral dose titration. If the dose of carvedilol is rapidly escalated (e.g., every 12 hours), then doses will have a tendency to stack – and eventually, this may lead to hypotension.

Oral antihypertensives

A summary on commonly used oral antihypertensive medications in hypertensive emergencies is provided in the following table.

RECAP

- Epistaxis, proteinuria, chronic renal failure, and headache Do NOT account for target organ damage.

- Do not aggressively treat scary blood pressure without the presence of target organ damage. These are not hypertensive emergencies.

- Try to identify life-threatening conditions associated with elevated BP e.g. aortic dissection, ICH, etc.

- The most suitable IV antihypertensive medications for hypertensive emergencies are those with fast onset and short duration of action (titratable antihypertensive medications).

- For most hypertensive emergencies, MAP should be reduced gradually by approximately %20 percent in the first hour and by a further 5 to 15% over the next 23 hours.

- A few exceptions where immediate BP lowering is warranted include AIS, ICH, and Aortic dissection. See table above.

- Avoid dropping the BP too much and too fast.

- Most hypertensive emergency patients are volume-depleted due to the phenomenon of pressure natriuresis. If BP drops following IV antihypertensive, evaluate volume status and consider IV fluid administration.

- IV hydralazine and nitroprusside have erratic effects and are not suitable for initial control of hypertensive emergencies.

- Metoprolol (IV or PO) drops the heart rate but is relatively ineffective for controlling blood pressure.

- Start oral medications after a suitable period (often 8 to 24 hours) of BP control at target in an intensive care unit and taper down and discontinue the initial intravenous therapy.

- Once trying to transition from an antihypertensive infusion to oral medications, choose the agents with fast onset and short duration of action.

- Amlodipine takes a long time to work and has no place in the treatment of hypertensive emergencies.

Going further

- Hypertensive emergencies (Emergency Medicine Cases)

- Emergencies with a Side of Hypertension (EMCrit)

- Hypertensive emergency (IBCC)

References

1. Astarita A, Covella M, Vallelonga F, Cesareo M, Totaro S, Ventre L, Aprà F, Veglio F, Milan A. Hypertensive emergencies and urgencies in emergency departments: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2020 Jul;38(7):1203-1210. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000002372. PMID: 32510905

2. Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, Clement DL, Coca A, de Simone G, Dominiczak A, Kahan T, Mahfoud F, Redon J, Ruilope L, Zanchetti A, Kerins M, Kjeldsen SE, Kreutz R, Laurent S, Lip GYH, McManus R, Narkiewicz K, Ruschitzka F, Schmieder RE, Shlyakhto E, Tsioufis C, Aboyans V, Desormais I; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018 Sep 1;39(33):3021-3104. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2019 Feb 1;40(5):475. PMID: 30165516.

3. van den Born BH, Lip GYH, Brguljan-Hitij J, Cremer A, Segura J, Morales E, Mahfoud F, Amraoui F, Persu A, Kahan T, Agabiti Rosei E, de Simone G, Gosse P, Williams B. ESC Council on hypertension position document on the management of hypertensive emergencies. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2019 Jan 1;5(1):37-46. doi: 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvy032. Erratum in: Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2019 Jan 1;5(1):46. PMID: 30165588.

4. Peixoto AJ. Acute Severe Hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2019 Nov 7;381(19):1843-1852. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1901117. PMID: 31693807

5.Johnson W, Nguyen ML, Patel R. Hypertension crisis in the emergency department. Cardiol Clin. 2012 Nov;30(4):533-43. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2012.07.011. Epub 2012 Oct 2. PMID: 23102030

6. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, MacLaughlin EJ, Muntner P, Ovbiagele B, Smith SC Jr, Spencer CC, Stafford RS, Taler SJ, Thomas RJ, Williams KA Sr, Williamson JD, Wright JT Jr. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018 Jun;71(6):1269-1324. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066. Epub 2017 Nov 13. Erratum in: Hypertension. 2018 Jun;71(6):e136-e139. Erratum in: Hypertension. 2018 Sep;72(3):e33. PMID: 29133354

7. Jolly H, Freel EM, Isles C. Management of hypertensive emergencies and urgencies: narrative review. Postgrad Med J. 2021 Oct 20:postgradmedj-2021-140899. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2021-140899. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34670853.

8. Leiba A, Cohen-Arazi O, Mendel L, Holtzman EJ, Grossman E. Incidence, aetiology and mortality secondary to hypertensive emergencies in a large-scale referral centre in Israel (1991-2010). J Hum Hypertens. 2016 Aug;30(8):498-502. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2015.115. Epub 2015 Dec 17. PMID: 26674757.

9. Elliott WJ. Clinical features in the management of selected hypertensive emergencies. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2006 Mar-Apr;48(5):316-25. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2006.02.004. PMID: 16627047

Add comment