27 January, 2023 by Shahriar Lahouti.

CONTENTES

- Preface

- Epidemiology and risk factors

- Definition and diagnostic criteria

- Pathophysiology

- Clinical presentation

- Differential diagnosis

- Evaluation

- Management

- Appendix

- Going further

- References

Preface

Preeclampsia is a multisystem progressive disorder characterized by the new onset of hypertension plus either proteinuria or signs of end-organ dysfunction in the last half of pregnancy or postpartum. Preeclampsia is a major cause of maternal and perinatal mortality and morbidity. This post reviews the definition, pathogenesis, clinical features, and critical aspects of management of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

Epidemiology

It has been estimated that preeclampsia complicates 4.6% of pregnancies globally, and is a significant cause of maternal and perinatal death *.

- 0.5% of women with preeclampsia without severe features, and as many as 2-3% of patients with severe preeclampsia who are not receiving antiseizure prophylaxis will develop eclampsia *.

- Patients with severe preeclampsia are at higher risk of developing HELLP syndrome (1-2%), and placental abruption (~3%) *.

- Preeclampsia can lead to fetal growth restriction (FGR) and oligohydramnios as well as medically or obstetrically indicated preterm birth.

- FGR is more prevalent (~18%) in women with early-onset preeclampsia (i.e. with onset of preeclampsia <34 weeks of gestation) than those with late-onset preeclampsia (14.0%) *.

Risk factors for preeclampsia(relative risk “RR”)

- A past history of preeclampsia (RR 8.4)*

- Chronic hypertension (RR 5.1)

- Pregestational diabetes (RR 3.7)

- Multifetal pregnancy (RR 2.9)

- Nulliparity (RR 2.1)

- Thrombophilia and some autoimmune disorders

- Antiphospholipid syndrome (RR 2.8)

- systemic lupus erythematosus (RR 2.5)

- Pre-pregnancy body-mass index >30 kg/m²(RR 2.8)

- Chronic kidney disease (RR 1.8)

- Advanced maternal age ( age >35 years: RR 1.2; age > 40 years: RR 1.5)

Definition and diagnostic criteria

During pregnancy, hypertension is defined as SBP ≥140 mmHg and/or DBP ≥90 mmHg on at least 2 occasions 4h apart *.

- In the setting of severe hypertension (SBP ≥160 and/or DBP ≥110), the diagnosis can be confirmed in a shorter interval to facilitate timely treatment (i.e. persistent HTN on two occasions at least 15 min apart).

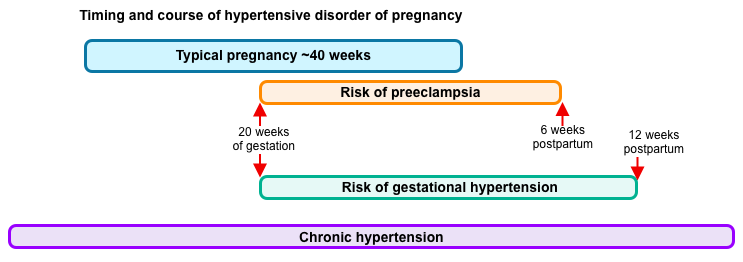

The major hypertensive disorders that occur in pregnant patients are described here *.

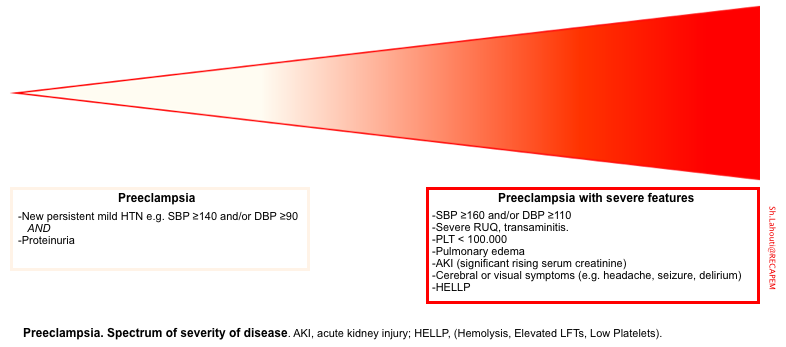

| Preeclampsia Refers to HTN which is developing or worsening after 20w of gestation (or within 6w of postpartum period) accompanied by end-organ dysfunction w/wo proteinuria. 👉Note that proteinuria is not required for making diagnosis, if HTN is accompanied by signs or symptoms of end-organ dysfunction *. |

- Preeclampsia: Diagnosis is made when all following 3 criteria are met.

-

- HTN: New onset of HTN, or worsening / resistant hypertension after 20 weeks of gestation:

- SBP ≥140 or DBP ≥90

- SBP ≥160 or DBP ≥110

- Any of the following new onset conditions

- Proteinuria ≥0.3 g in a 24-hour urine specimen (or a spot protein/creatinine ratio ≥0.3 mg/mg).

- Acute kidney injury: Serum creatinine >1.1 mg/dL or doubling of the creatinine concentration.

- Pulmonary edema

- Neurological complications (e.g. Severe persistent headache, seizure, altered mental state, hyperreflexia, or persistent visual scotomata).

- Thrombocytopenia <100,000/mm3.

- Transaminitis > x2 the ULN.

- Severe persistent right upper quadrant or epigastric pain unresponsive to medications.

- Proteinuria ≥0.3 g in a 24-hour urine specimen (or a spot protein/creatinine ratio ≥0.3 mg/mg).

- Exclusion of other diagnoses (see below).

- HTN: New onset of HTN, or worsening / resistant hypertension after 20 weeks of gestation:

| Chronic hypertension Defined as HTN diagnosed before pregnancy or is present on at least two occasions before 20 w of gestation or persists longer than 12w postpartum *. |

- Chronic HTN with superimposed preeclampsia

- A sudden increase in BP that was previously well-controlled, or

- New onset of proteinuria or a sudden increase in proteinuria in a patient with known proteinuria before pregnancy, or

- Significant new end-organ dysfunction consistent with preeclampsia after 20w of gestation or postpartum.

| Gestational hypertension Refers to HTN w/o proteinuria or other signs/symptoms of preeclampsia-related end-organ dysfunction that develops after 20w of gestation. The elevated BP should return to normal by 12w postpartum. |

- Gestation HTN is a provisional diagnosis for hypertensive pregnant who do not meet criteria for preeclampsia or chronic HTN. Hence, the diagnosis is changed to:

- Preeclampsia: if proteinuria or new signs of end-organ dysfunction develop (i.e. criteria for preeclampsia are met).

- Chronic HTN: if blood pressure elevation persists ≥12w postpartum.

| HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets) It appears to be a subtype of severe preeclampsia (not a separate disorder) in which hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and thrombocytopenia are the predominant feature. |

- HELLP Syndrome (Hemolysis, Elevated LFTs, Low Platelets). All of the following criteria are required to diagnose HELLP *:

- Hemolysis, established by at least 2 of the following:

- Blood smear: shistocytes or burr cells

- Bill ≥1.2 mg/dL

- Serum haptoglobin ≤25 mg/dL, or LDH>600 IU/L

- Severe anemia, unrelated to blood loss.

- Blood smear: shistocytes or burr cells

- Elevated Liver enzymes (AST or ALT ≥ x2 the ULN)

- Low platelets <100,000/mm3

- Hemolysis, established by at least 2 of the following:

| Eclampsia Refers to new-onset of tonic-clonic seizures in a patient with hypertensive disorder of pregnancy that cannot be attributed to other causes. |

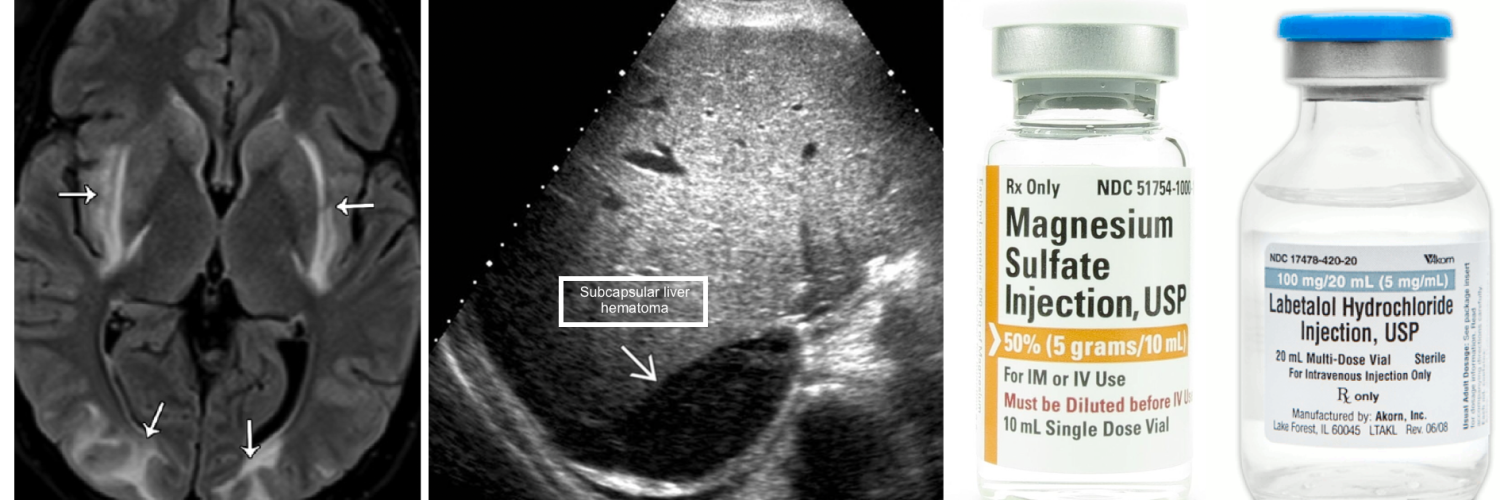

| Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome (PRES) PRES is a clinicoradiologic diagnosis, refering to constellation of signs and symptoms (e.g. HTN, seizure, delirium, headache, and visual symptoms); accompanied by bilateral vasogenic edema predominantly in posterior brain. Several causes have been recognized contributing to pathogenesis of PRES. In the context of pregnancy, PRES is frequently caused by preeclampsia, so these pathologies frequently coexist. |

Pathophysiology

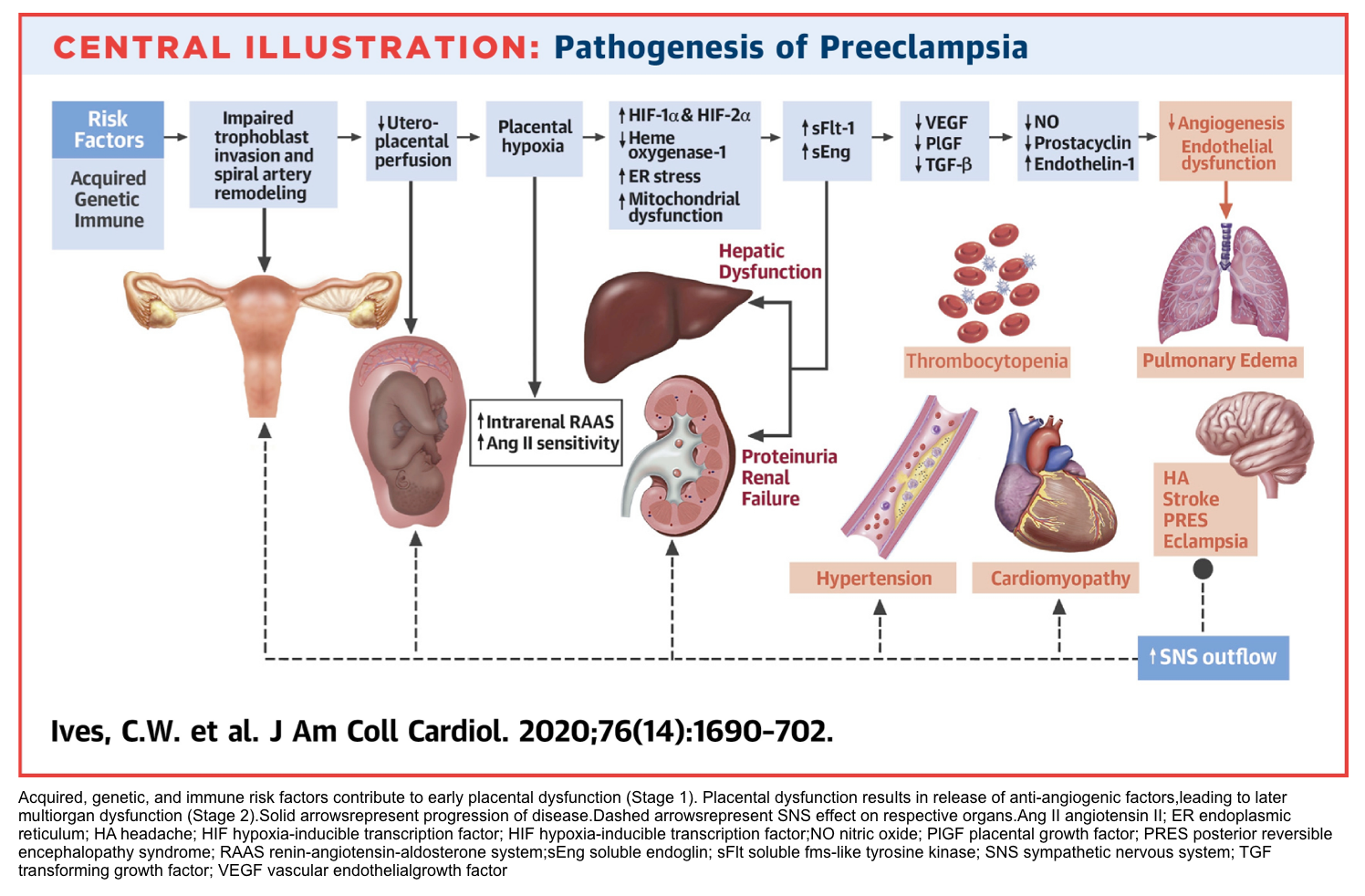

The pathogenesis of preeclampsia likely involves both maternal and fetal/placental factors. Several mechanisms of disease have been proposed in including chronic uteroplacental ischemia, immune maladaptation and an exaggerated maternal inflammatory response to deported trophoblasts.

- Abnormal development of the placental vasculature early in pregnancy is a key event that results in relative placental underperfusion, hypoxia and ischemia. This leads to release of anti-angiogenic factors into the maternal circulation *.

- These factors alter maternal systemic endothelial function. The resulting vascular changes also cause changes in hemoconcentration, vascular spasm, capillary leak, and the risk of pulmonary edema with excessive fluid resuscitation as well as other clinical manifestations of the disease (hypertension and hematologic, neurologic, cardiac, renal, and hepatic dysfunction).

Clinical presentation

Onset

- Preeclampsia usually occurs between 20 weeks of gestation and about 6 weeks postpartum.

- Rarely preeclampsia can occur earlier than 20 weeks in patients with molar pregnancies*.

Spectrum of disease severity

- Preeclampsia has a spectrum of severity. Most patients with preeclampsia present with new onset of hypertension (which may not be impressive in an absolute sense). Only 25% of patients develop signs and symptoms which characterize the severe end of the disease spectrum.

Typical presentations

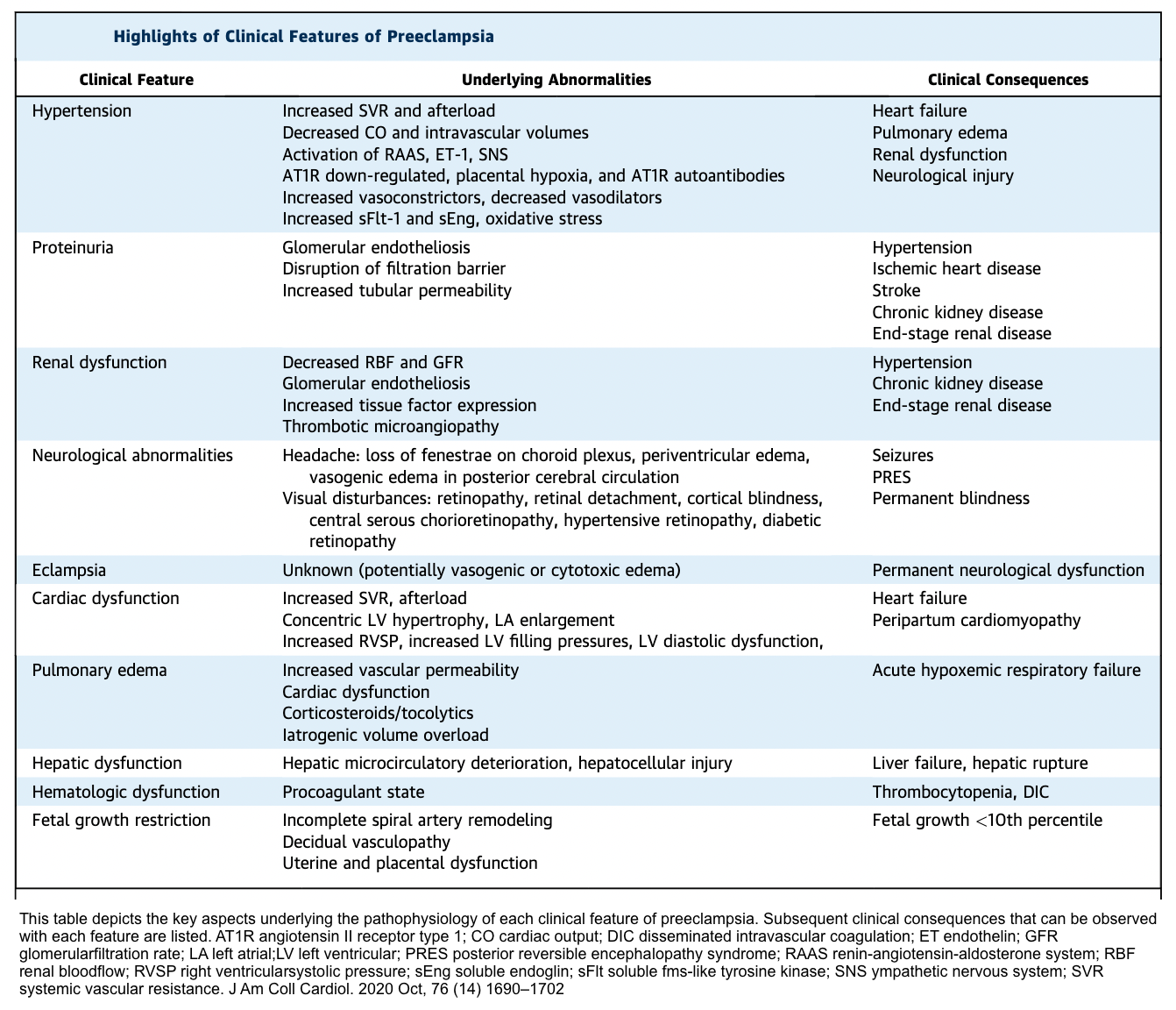

The highlights of clinical features of preeclampsia is summarized in following table *.

Hypertension

- HTN is due to increased peripheral vascular resistance.

- It is the most common clinical clue to the presence of the preeclampsia.

- All patients with preeclampsia have hypertension, however a small proportion of those with HELLP and rare patients with eclampsia do not meet current diagnostic criteria for hypertension.

Generalized edema

- Leg swelling is common in pregnancy and non-diagnostic. However, a sudden increase in edema or new edema (particularly of the hands or face) is concerning for preeclampsia.

- Edema is due to capillary leak from endothelial damage and/or increased sodium retention that may be related to glomerular endotheliosis and proteinuria.

Oliguria (urine output < 100 mL over 4h)

- Oliguria in preeclampsia is due to contraction of the intravascular space secondary to vasospasm, leading to increased renal sodium and water retention, as well as intrarenal vasospasm.

- 💡Avoid excessive volume administration in attempts to stimulate urine output, as this carries risk of developing pulmonary edema.

Pulmonary edema

- It is a feature of the severe end of the disease spectrum.

- 10% of preeclampsia with severe features develop pulmonary edema.

- The etiology is multifactorial e.g. ↑pulmonary vascular hydrostatic pressure, ↓plasma oncotic pressure, capillary leak from endothelial activation, left heart failure, acute severe hypertension, and iatrogenic volume overload.

- Signs and symptoms: shortness of breath, cough, wheezing, anxiety/restlessness, chest pain, palpitations, or excessive perspiration, and SpO2 < 94%.

HELLP Syndrome (Hemolysis, Elevated LFTs, Low Platelets)

- HELLP syndrome is a manifestation of severe preeclampsia (not a separate disorder).

- Pathogenesis: Growing evidence shows that HELLP is a thrombotic microangiopathy, which affects mostly the liver and more rarely the kidney.

- Microangiopathy and activation of intravascular coagulation can account for all of the laboratory findings in HELLP syndrome.

- Clinical symptoms: Nausea, vomiting and RUQ pain.

- Laboratory findings *:

- Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (e.g. high LDH, low haptoglobin, schistocytes on blood smear, severe anemia not otherwise explained)

- Elevated AST and ALT (above twice the upper limit of normal).

- Platelets <100,000/mm3.

- May cause hepatic hematoma that ruptures, leading to hemoperitoneum.

- Differential diagnosis and treatment below.

Vaginal bleeding, mild moderate abdominal pain and uterine contraction:

- These may represent development of placental abruption in preeclamptic patients.

- 🚩If placental separation is > 50%, there’s a high risk of “DIC”, which is present in ~15% of abruptions with death of the fetus.

A fundal height that measures less than expected may indicate fetal growth restriction and/or oligohydramnios.

Neurologic

- Headache

- Is a feature of the severe end of the disease spectrum.

- Mechanism: It may result from generalized endothelial cell dysfunction, leading to vasospasm of the cerebral vasculature, or it may result from loss of cerebrovascular autoregulation, leading to areas of both vasoconstriction and forced vasodilation.

- In this context, it represents a form of posterior reversible leukoencephalopathy syndrome (PRES).

- Although not pathognomonic, a feature that suggests preeclampsia-related headache rather than another type of headache is that it persists despite administration of over-the-counter analgesics.

- However, resolution of the headache with analgesics does not exclude the possibility of preeclampsia.

- Acetaminophen is commonly used to treat headache.

- Note: Doses ≤2 g/day can be administered to patients with mild hepatic or renal insufficiency, but it is contraindicated in patients with severe hepatic or renal impairment.

- Visual symptoms

- When present, are also symptoms of the severe end of the disease spectrum.

- Mechanism: Retinal arteriolar spasm, impaired cerebrovascular autoregulation, and cerebral edema.

- Visual symptoms may be a manifestation of PRESS.

- Symptoms include

- Blurred vision, photopsia (flashing lights or sparks), and scotomata (dark areas or gaps in the visual field) *.

- Diplopia or amaurosis fugax (blindness in one or both eyes) may also occur.

- Cortical blindness is rare and typically transient.

- Mental status changes include confusion and altered behavior, such as agitation.

- Generalized hyperreflexia is a common finding. Sustained ankle clonus may be present.

- Seizure

- Seizure in a preeclamptic patient upstages the diagnosis to eclampsia 👇.

Eclampsia is the convulsive manifestation of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

- It is defined as new-onset tonic-clonic (or rarely focal, or multifocal seizures) in the absence of other causative conditions (see below)

- 1.9% of patients with preeclampsia and 3.2% of patients with severe preeclampsia can develop eclampsia.

- In a nationwide analysis of cases of eclampsia, a significant proportion of women (20–38%) do not demonstrate the classic signs of preeclampsia (hypertension or proteinuria) before the seizure episode. Thus, the notion that preeclampsia has a natural linear progression from preeclampsia without severe features to preeclampsia with severe features and eventually to eclamptic convulsions is inaccurate.

- Clinical signs and symptoms of eclampsia

- Premonitory signs (80%): severe and persistent headaches, blurred vision, photophobia, and altered mental status.

- Of note, premonitory signs are absent in ~20% of patients.

- Eclamptic seizure

- Generalized tonic-clonic seizure with abrupt loss of consciousness (most common).

- Focal or multifocal seizures or coma can happen but are less common.

- The ictal phase typically is self-limited and last 1-3 min.

- Most patients begin to recover responsiveness within 10-20 min after the generalized convulsion.

- Focal neurologic deficits are generally absent.

- Premonitory signs (80%): severe and persistent headaches, blurred vision, photophobia, and altered mental status.

- Diagnosis

- Eclampsia is a clinical diagnosis.

- A typical new-onset tonic-clonic seizures in a patient with a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy is diagnostic for eclampsia.

- These patients usually do not require diagnostic evaluation beyond that for preeclampsia (below).

- Neuroimmaging

- Some patients with atypical presentation may require neuroimaging to exclude an alternative pathology (e.g. intracranial hemorrhage). See below.

- The neuroimmaging findings in (pre)eclampsia include:

- Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome (PRES) is the most common finding *. More on this,👉 here.

- Bilateral vasogenic edema which is most often located in the parito-occipital regions.

- Edema may be seen as hypodense on CT scanning. MRI reveals vasogenic edema as bright on T2/FLARE sequences (~98% of patients with eclampsia in one series had PRES on their MRI scans *).

- Diffusion restriction (implying cytotoxic edema), less commonly may be seen in more severe cases, and may be irreversible.

- This may reflect the presence of superimposed vasospasm (e.g. overlap between Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome and Reversible Cerebral Vasoconstriction Syndrome)*.

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage and small cortical hemorrhages (especially in the parietooccipital and occipital regions), rarely may be seen in very severe cases*.

- Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome (PRES) is the most common finding *. More on this,👉 here.

- Eclampsia is a clinical diagnosis.

Potential laboratory findings

- Proteinuria in preeclampsia can be defined as any of the following:

- ≥0.3 g protein in a 24-hour urine specimen.

- A spot protein/creatinine ratio ≥0.3 mg/mg can be used as a quick reliable alternative to diagnose significant proteinuria *,*.

- Protein ≥2+ on a paper test strip dipped into a fresh, clean voided midstream urine specimen (only if one of the above quantitative methods is not available).

- Although urine dipstick showing proteinuria is nonspecific, a negative dipstick can often be used to exclude significant proteinuria. A urinary dipstick showing 2+ or higher reading is strongly suggestive of clinically significant proteinuria *.

- Elevated serum creatinine to >1.1 mg/dL or doubling of the creatinine concentration in the absence of other renal disease.

- Thrombocytopenia <100,000/mm3.

- Transaminitis above twice the upper limit of the normal (AST predominant).

- AST is increased to a greater extent than ALT in preeclampsia, and is related to periportal necrosis.

- This may help in distinguishing preeclampsia from other potential causes of parenchymal liver disease in which ALT usually is higher than AST.

- Elevated LDH

- It can be caused by hepatic dysfunction (LDH derived from ischemic, or necrotic tissues, or both) and hemolysis (LDH from red blood cell destruction).

- Hemolysis (blood smear, bill ≥1.2 mg/dL, LDH>600 IU/L, serum haptoglobin ≤25 mg/dL)

- The total bilirubin level is increased as a result of an increase in the unconjugated fraction from hemolysis.

Differential diagnosis

When evaluating patients for possible preeclampsia, it is generally safer to assume that new-onset hypertension in pregnancy is due to preeclampsia, even if all the diagnostic criteria are not fulfilled and the blood pressure is only mildly elevated, since preeclampsia may progress to eclampsia or other severe forms of the disease in a short period of time. However, several other disorders can manifest some or many of the signs and symptoms of preeclampsia.

The differential diagnosis of pregnant patients with hypertension and myriad of clinical symptoms are presented below.

DDx among patients whose primary finding is hypertension

- Gestational HTN

- Preeclampsia

- Chronic HTN

- Exacerbation of chronic kidney disease

- Endocrine: Thyroid storm, pheochromocytoma, cushing syndrome

- Drugs: Sympathomymetic intoxication (e.g. cocaine, amphetamine(s), and phencyclidin) or withdrawal of short-acting antihypertensive agents (especially clonidine, propranolol or other beta blockers)

- Dysautonomia: Guillain-Barré syndrome, paroxysmal sympathetic hyperactivity, multiple system atrophy syndrome.

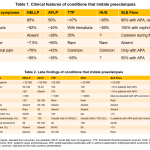

DDx among patients with HTN and thrombocytopenia or transaminitis (see appendix for distinguishing clinical and lab features *).

- Preeclampsia (with severe features)

- HELLP

- Acute fatty liver of pregnancy

- Thrombotic microangiopathy: TTP and HUS

- SLE flare

- Antiphospholipid syndrome

DDx among patients with HTN and RUQ/epigastric abdominal pain

- Preeclampsia (with severe features)

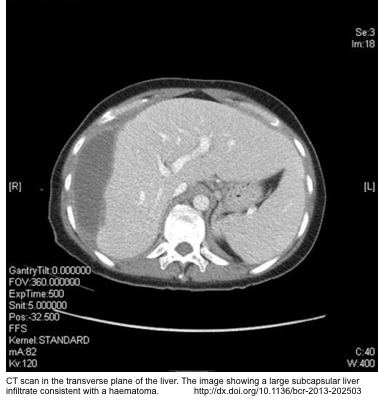

- More on radiologic findings of subcapsular hematoma in HELLP here.

- Hepatitis

- Cholecystitis/cholangitis

- Pancreatitis

- Liver abscess

- Budd-Chiari syndrome

- Portal vein thrombosis

DDx among patients with HTN and neurological complications such as headache, seizure, delirium *

- Preeclampsia/eclampsia.

- 98% of patients with eclampsia show PRES on their MRI scans. More on PRES neuroimaging here.

- Eclampsia

- Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura (TTP)

- Migraine

- Pituitary apoplexy

- Cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT). See more here.

- CVA: Ischemic stroke/ ICH /SAH

- Breakthrough seizure

- Metabolic: Hypoglycemia, Wernicke’s encephalopathy (may result from hyperemesis gravidarum)

- Intoxication or withdrawal.

- Intracranial infection e.g. meningitis

- Malignancy e.g. metastatic choriocarcinoma, meningioma *

DDx among patients with HTN and visual disturbances

- Preeclampsia/eclampsia/PRES

- Retinal detachment

- POCUS can be helpful for diagnosis. See POCUS in 👉 retinal detachment. More on this here.

- Retinal vein occlusion

DDx among patients with HTN and dyspnea

- Pulmonary edema secondary to preeclampsia

- Left heart failure e.g. postpartum cardiomyopathy, Valvular / congenital heart disease

- Pulmonary embolism

- Fat embolism, amniotic fluid embolism

- Malignancy e.g. metastatic choriocarcinoma

Evaluation

Basic evaluation for patients with preeclampsia

- Blood count, electrolytes.

- Liver chemistry

- Serum creatinine level

- Urinalysis and urinary protein determination (protein to creatinine ratio in a random urine specimen or 24-hour urine collection for total protein)

Additional studies

- Coag. study (INR, PTT, fibrinogen, D-dimer) and haptoglobin.

- These are not routinely obtained but are indicated in patients with additional complications, such as placental abruption, severe bleeding, thrombocytopenia, or severe liver dysfunction.

- LDH, ammonia and glucose (in patients with RUQ abdominal pain or those with severe liver dysfunction)

- Cultures: If infection suspected

- Lumbar puncture

- It is not generally performed, but might be considered if there is concern for alternative diagnoses (e.g. meningitis).

- In preeclampsia the CSF will often be normal. However, protein levels and opening pressure may be elevated.

- Neuroimaging

- May be indicated in some patients to exclude an alternative pathology (e.g.intracranial hemorrhage).

- Indication for further investigation including neuroimmaging *

- Pregnant individuals who do not meet criteria for diagnosis of preeclampsia, HELLP syndrome, or gestational hypertension.

- Even if criteria for a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy are not met, the diagnosis can be made in a pregnant person with seizures who has the typical clinical and neuroimaging findings of reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome (headache, confusion, visual symptoms, vasogenic edema predominantly localized to the posterior cerebral hemispheres)

- Persistent neurologic deficits

- Prolonged loss of consciousness

- Onset of seizures >48 hours after delivery

- Onset of seizures before 20 weeks of gestation

- Seizures despite adequate magnesium sulfate therapy.

- Pregnant individuals who do not meet criteria for diagnosis of preeclampsia, HELLP syndrome, or gestational hypertension.

Approach to management

- Preeclampsia/HELLP/eclampsia are progressive disorders and no drug has been discovered to slow disease progression.

- Therefore the only option to stop the disease is to deliver the fetus and placenta.

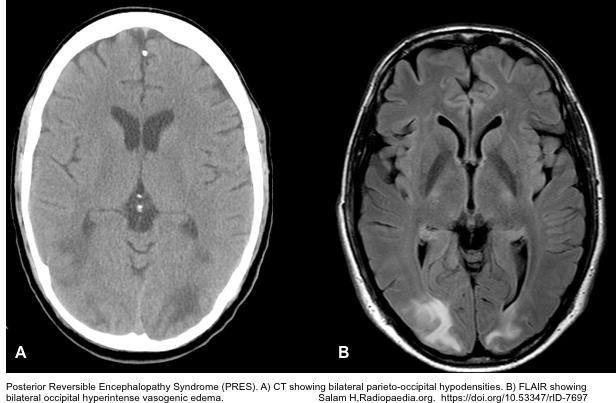

- The overall approach to management is to deliver the baby and placenta at term gestation, or, if preterm preeclampsia is diagnosed, to try expectant management of the pregnancy (if possible) until a more advanced gestation is reached (table below).

- The general schema of management plan involves:

-

Activate the multidisciplinary team: Obstetrics, neonatology, pediatrics

- Monitor the woman and baby closely.

- Assess fetal status, but maternal resuscitation takes precedence.

- Assess ‘ABC’ of the mother.

-

If >20 weeks gestation, place the patient in the left lateral tilt position or manually displace the uterus to the left. Confirm the blood pressure.

- Assess fetal status, but maternal resuscitation takes precedence.

- Management of hypertension and seizure (prophylaxis and treatment) is discussed in detail below.

- Consider to give corticosteroid to promote fetal lung maturity; for preterm labor between 24 and 34 weeks gestational age when delivery is not an immediate possibility.

- Betamethasone 12mg IM q24h x 2 or Dexamethasone 6mg IM q12h.

-

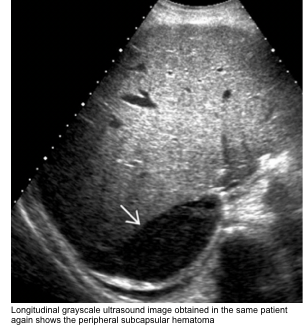

Management of hypertension

Antihypertensive treatment should be initiated expeditiously for SBP ≥160 and/or DBP ≥105 (MAP >120)*.

- Objective of treatment

- To prevent end-organ damage e.g. congestive heart failure, MI, renal injury or failure, and ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke.

- Target

- The initial goal is decreasing MAP by ~20%.

- Subsequently, the blood pressure should be gradually decreased to a target MAP of roughly ~100 mm Hg. This target should be individualized (depending on the baseline blood pressure).

- Antihypertensive agents

- A recent Cochrane systematic review found no significant differences regarding either efficacy or safety between hydralazine and labetalol or between hydralazine and calcium channel blockers.

- ⚠️Avoid using ACEIs, diuretics, nitroprusside in pregnancy because of potential safety concerns.

- Treatment with hydralazine is not widely available anymore and not recommended as it has been associated with adverse perinatal outcomes *. Consider hydralazine only if other agents are not available.

- IV antihypertensive may be suitable for initial treatment. These are listed in the following table. (Drag the horizontal scroll bar to see the full contents).

- A recent Cochrane systematic review found no significant differences regarding either efficacy or safety between hydralazine and labetalol or between hydralazine and calcium channel blockers.

| Drug | Onset of action | Duration of action | Dose | ⚠️Contraindications | Adverse effects |

| Labetalol IV | 5-10 min | 3-6h | Load with sequential pushes of 20mg- 40mg-80mg-80mg-80mg (q15min PRN). If an initial total dose of 300mg does not work, shift to another agent. A continuous IV infusion of 1 to 2 mg/minute can be used instead of intermittent therapy or started after 20 mg IV dose. To prevent fetal bradycardia, the cumulative dose should not exceed 800 mg/24 hours *. | History of 2nd or 3rd degree AV block CPE Asthma Bradycardia | Bronchoconstriction Fetal bradycardia Hyperkalemia |

| Nicardipine IV | 5-15 min | 30-40 min | Start at 5mg/h. If BP is above the target, increase by 2.5mg/h q15-30min. When BP reaches target, decrease the infusion to 3-5mg/h. If BP below the target, hold promptly. | Liver failure Severe aortic stenosis | Headache Reflex tachycardia Volume overload (often requires large amount of saline infusion) |

| Nitroglycerine IV | 1-5 min | 3-5 min | 5-300 mcg/min | Elevated ICP | Headache Reflex tachycardia |

| Hydralazine IV | 5-20 min | 1-4h | Start with 5mg IV. Additional dose of 5-10mg may be given q20-40min to a max dose of 40mg initially. | Coronary artery disease Mitral valve rheumatic heart disease Hypovolemia HOCM or LVOTO | Unpredictable overshoot hypotension Headache Tachycardia Associated more with abnormal fetal heart rate tracing SLE-type syndrome |

| Nifedipine (immediate release) “PO” | 15-20 min | 8h | 10mg PO. May repeat q30-60min as needed. No more use of 50mg initially. | Cardiogenic shock | Overshoot hypotension Headache Tachycardia |

-

- Oral medications can be started once patient is hemodynamically stabilized. Oral agent suitable during pregnancy include

- Labetalol

- Nifedipine (extended release)

- Hydralazine

- Prazosin

- Clonidine

- Methyldopa

- ⚠️Note that methyldopa is contraindicated in the presence of any active liver disease. Use with caution in renal insufficiency.

- Oral medications can be started once patient is hemodynamically stabilized. Oral agent suitable during pregnancy include

Volume management

Pathophysiologic background

- Preeclampsia causes endothelial dysfunction, leading to capillary leak and third spacing of fluids as well as increased risk of developing pulmonary edema.

- Volume management is challenging since despite that patients have reduced circulating volume, they cannot keep the administered volume intravascularly because of capillary leak.

- Generally, large-volume fluid resuscitation is often counterproductive (virtually worsening pulmonary and systemic edema).

Fluid management

- Fluid balance (input versus urine output plus estimated insensible losses [usually 30 to 50 mL/h]) should be monitored closely to avoid excessive fluid administration.

- A maintenance infusion of a balanced crystalloid at approximately 80 mL/h (~1mL/Kg/h) is often adequate for a patient who is “NPO” and has no ongoing abnormal fluid losses (e.g. bleeding) *.

- Avoid large volume of fluid to stimulate urine output in oliguric patients.

- Oliguria that does not respond to a modest fluid bolus (e.g. a 300 mL fluid challenge) suggests renal insufficiency. In these patients additional volume administration is not recommended *.

Seizure prophylaxis

Magnesium sulfate is the front-line antiepileptic drug in hypertensive disorder of pregnancy.

- Indications

- Preeclampsia with severe features, HELLP.

- Mechanism of action

- Raising the seizure threshold by its action at the n-methyl d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor.

- Membrane stabilization in the CNS secondary to its actions as a nonspecific calcium channel blocker.

- Decreasing acetylcholine transmission in motor nerve terminals.

- Vasodilatation of constricted cerebral vessels by opposing calcium-dependent arterial vasospasm.

- Preventing disruption of the blood-brain barrier caused by circulating small extracellular vesicles secreted into the plasma of patients with preeclampsia.

- Contraindications:

- Myasthenia gravis (since it can precipitate a severe myasthenic crisis).

- Severe hypocalcemia

- Heart block

👉In the presence of contraindications, alternative medications e.g. levetiracetam should be used.

- Duration

- The optimal duration of the magnesium infusion is not clear. Treatment is often continued until 24-48 h after delivery, when the patient is showing clinical signs of resolving preeclampsia.

- Administration

- IV route:

- When given via IV route, it should be diluted to a <20% solution.

- Loading dose: 4-6 g of a 10% solution IV over 15min.

- Maintenance infusion: 1 to 2 g/hour as a continuous infusion.

- IM (when IV access is not available)

- 5 g of a 50% solution IM into each buttock (total of 10 g) followed by 5 g IM q4h.

- IV route:

- Dosing in renal insufficiency

- MgSO4 is excreted by the kidneys. Patients with renal insufficiency should receive a standard loading dose, since their volume of distribution is not altered, but a reduced maintenance dose.

- If 1.1 < serum creatinine < 2.5 mg/dL: Give a loading dose of 4-6g IV, followed by continuous infusion of 1g/h.

- If serum creatinine ≥2.5 mg/dL or severe oliguria: Laod with 4-6g IV. Do not give a maintenance infusion.

- Follow electrolytes & magnesium levels q4-6hr. Give magnesium bolus based on serum level.

- MgSO4 is excreted by the kidneys. Patients with renal insufficiency should receive a standard loading dose, since their volume of distribution is not altered, but a reduced maintenance dose.

The serum magnesium concentration (in 3 different units) and toxicities are shown in following table *.

| mmol/L | mEq/L | mg/dL | Effect |

| 2–3.5 | 4–7 | 5-9 | Therapeutic range |

| >3.5 | >7 | >9 | Loss of patellar reflexes |

| >5 | >10 | >12 | Respiratory paralysis |

| >12.5 | >25 | >30 | Cardiac arrest |

👉Note that magnesium levels aren’t routinely monitored in women with normal renal function and absence of signs/symptoms of Mg toxicity.

- Monitoring

- Clinical assessment for magnesium toxicity

- This should be performed for all patients receiving continuous infusion by q1-2h.

- The maintenance dose is only allowed to be continued when:

- Patellar reflex is present (loss of reflexes is the first manifestation of symptomatic hypermagnesemia)

- RR > 12 b/m (serum Mg >12mg/dL causes muscle paralysis leading to flaccid quadriplegia, apnea and respiratory failure)

- Urine output is >100 mL over 4 h.

- When to check serum magnesium level?

- Patients with normal renal function do not require level check. Clinical evaluation as described above will be enough.

- Magnesium level should be check in the following conditions:

- Renal insufficiency with serum creatinine > 1.1 mg/dL. 👉Check Mg level q4-6h.

- Seizure while receiving magnesium sulfate.

- Clinical signs/symptoms suggestive of magnesium toxicity.

- Clinical assessment for magnesium toxicity

- How to manage patients with signs/symptoms of Mg toxicity?

- Stop the maintenance dose and check serum magnesium and all other electrolytes.

- If the serum Mg level is >9.6 mg/dL(8 mEq/L), the infusion should be stopped and serum magnesium levels should be determined at two-hour intervals.

- The infusion can be restarted at a lower dose when the serum level is <8.4 mg/dL (7 mEq/L).

- Stop the maintenance dose and check serum magnesium and all other electrolytes.

- MgSO4 side effects

- Common side effects: Diaphoresis, flushing, warmth, mild hypotension, and muscle weakness.

- Severe Mg toxicity may cause respiratory depression or heart block. The treatment is IV calcium (e.g. calcium gluconate).

- Magnesium therapy results in a transient reduction of total and ionized serum calcium concentration due to rapid suppression of parathyroid hormone release. Rarely, hypocalcemia becomes symptomatic (myoclonus, delirium, electrocardiogram abnormalities). Treatment is cessation of the magnesium infusion and administration of IV calcium.

Treatment of seizure

1# Immidiate management

- Most eclamptic seizures are self-limited.

- Magnesium sulfate is the first choice antiepileptic to prevent seizure recurrence.

- If patient has not yet received magnesium, load with 6 g IV and infuse as explained above.

- If patient has received magnesium, consider re-loading with 2-4 g IV.

- Infusion or maintenance doses as described above.

- Benzodiazepine may be used for status epilepticus (e.g. ongoing generalized seizure >5 min).

- IV access: Lorazepam 0.1 mg/kg IV bolus

- No IV access: Midazolam 10 mg IM

2# Refractory seixure to magnesium and benzodiazepines

- This is uncommon and may suggest another process (e.g. intracranial hemorrhage).

- Levetiracetam may be added as a second-line agent after magnesium.

- Be prepared for early intubation and propofol infusion.

Treatment of HELLP syndrome

- HELLP is a subtype of preeclampsia with severe features.

- Antihypertensive therapy: in patients with severe HTN, treat HTN in the same fashion as preeclampsia (discussed above).

- Seizure prophylaxis: Magnesium sulfate is indicated in all patients with HELLP syndrome.

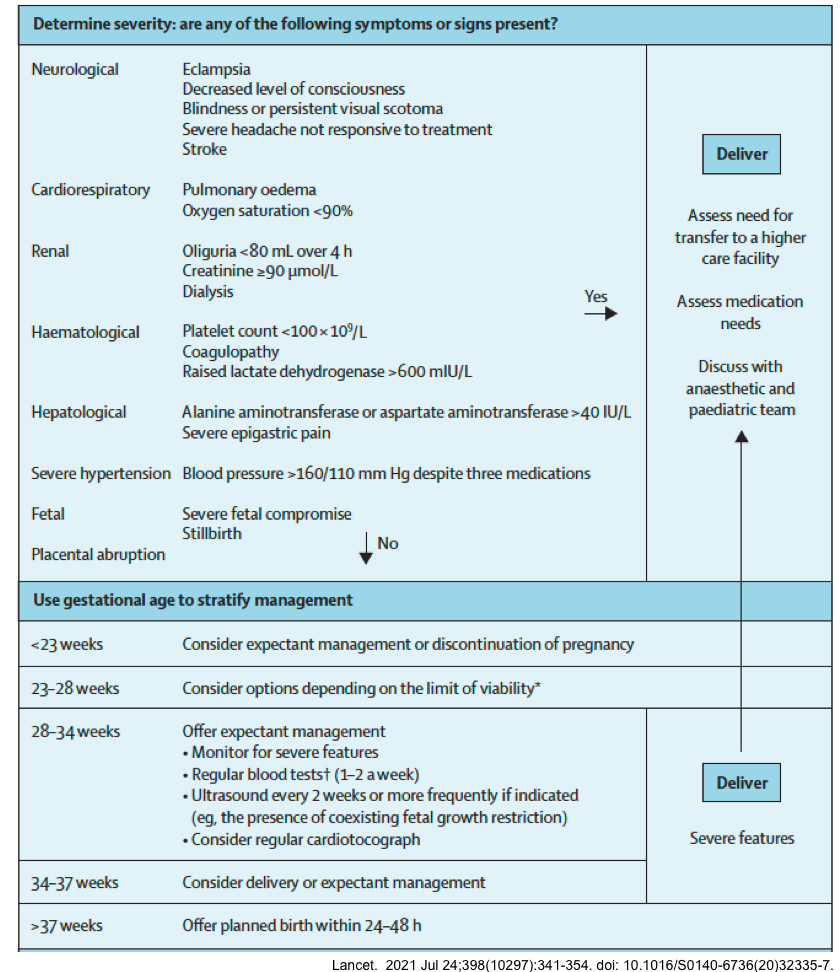

- Subcapsular liver hematoma

- It should be suspected in patients with preeclampsia/HELLP, presenting with severe RUQ pain.

- The hematoma may remain contained or may rupture the liver capsule.

- Diagnosis is based on ultrasonography (figure below).

- Management involve:

- Volume replacement and transfusion of blood and blood products, as needed.

- A team experienced in liver trauma surgery should be consulted during maternal stabilization and prior to delivery.

- Indication for transfusion and blood products

- Red cell transfusion: Indicated if the Hb is <7 g/dL and/or if the patient has ecchymosis, severe hematuria, or suspected abruption.

- PLT transfusion: Indicated in the following conditions

- Actively bleeding patients with thrombocytopenia.

- PLT <20.000 and planning for vaginal deliveries.

- PLT < 50.000 and planning for C-section deliveries *.

- PLT < 70.000 when neuraxial anesthesia procedure is planned.

- The platelet count necessary to safely perform neuraxial anesthesia is unknown. In the absence of other coagulation abnormalities, neuraxial anesthesia procedures are generally safe for patients with a platelet count ≥70,000/microL, with close follow-up for signs of spinal epidural hematoma *.

- 👉Note that assessment for PLT transfusion is multidimensional, i.e. considering PLT count, PLT function, presence of coagulopathy, invasiveness of procedure.

- Definitive treatment

- Delivery of fetus and placenta.

- Role of other therapeutic options

- Plasma exchange?

- It has no benefit in HELLP, but is the mainstay of treatment in TTP.

- Complement directed therapy?

- HELLP could share many similarities with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS), which is caused by dysregulated complement activation *.

- In a case report of a patients with severe early HELLP, treatment with eculizumab, a targeted inhibitor of complement protein C5, was associated with marked clinical improvement and complete normalization of laboratory parameters for 16 days *.

- Eculizumab might be considered in cases of HELLP which closely resemble atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (e.g. prominent microangiopathic hemolytic anemia with low complement levels). Nonetheless, given that data on eculizumab in pregnancy are limited, it is not possible to completely exclude risks for both mother and fetus in treating HELLP syndrome and further studies are warranted.

- Plasma exchange?

Appendix

Clinical and laboratory features of conditions that imitate preeclampsia

Going further

References

1. PMID: 23746796. Abalos E, Cuesta C, Grosso AL, Chou D, Say L. Global and regional estimates of preeclampsia and eclampsia: a systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013 Sep;170(1):1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.05.005. Epub 2013 Jun 7.

2. PMID: 15284724. Sibai BM. Magnesium sulfate prophylaxis in preeclampsia: Lessons learned from recent trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004 Jun;190(6):1520-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.12.057.

3. PMID: 8092235. Sibai BM, Mercer BM, Schiff E, Friedman SA. Aggressive versus expectant management of severe preeclampsia at 28 to 32 weeks’ gestation: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994 Sep;171(3):818-22. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(94)90104-x.

4. PMID: 27094586. Bartsch E, Medcalf KE, Park AL, Ray JG; High Risk of Pre-eclampsia Identification Group. Clinical risk factors for pre-eclampsia determined in early pregnancy: systematic review and meta-analysis of large cohort studies. BMJ. 2016 Apr 19;353:i1753. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i1753.

5. PMID: 32443079. Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 222. Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jun;135(6):e237-e260. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003891.

6. PMID: 29899139. Brown MA, et al. International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy (ISSHP). Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy: ISSHP Classification, Diagnosis, and Management Recommendations for International Practice. Hypertension. 2018 Jul;72(1):24-43. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.10803.

7. PMID: 28005587. Ditisheim A, Sibai BM. Diagnosis and Management of HELLP Syndrome Complicated by Liver Hematoma. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Mar;60(1):190-197. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000253.

8. PMID: 33004135. Ives CW, Sinkey R, Rajapreyar I, Tita ATN, Oparil S. Preeclampsia-Pathophysiology and Clinical Presentations: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Oct 6;76(14):1690-1702. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.08.014.

9. PMID: 18773629. Hou JL, Wan XR, Xiang Y, Qi QW, Yang XY. Changes of clinical features in hydatidiform mole: analysis of 113 cases. J Reprod Med. 2008 Aug;53(8):629-33.

10. PMID: 22495060. Roos NM, Wiegman MJ, Jansonius NM, Zeeman GG. Visual disturbances in (pre)eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2012 Apr;67(4):242-50. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e318250a457.

11. PMID: 33630183. Gewirtz AN, Gao V, Parauda SC, Robbins MS. Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2021 Feb 25;25(3):19. doi: 10.1007/s11916-020-00932-1.

12. PMID: 27831835. Kanekar S, Bennett S. Imaging of Neurologic Conditions in Pregnant Patients. Radiographics. 2016 Nov-Dec;36(7):2102-2122. doi: 10.1148/rg.2016150187.

13. PMID: 22335428. Cade TJ, Gilbert SA, Polyakov A, Hotchin A. The accuracy of spot urinary protein-to-creatinine ratio in confirming proteinuria in pre-eclampsia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012 Apr;52(2):179-82. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2011.01409.x. Epub 2012 Feb 15.

14. PMID: 31635598. Moodley J, Soma-Pillay P, Buchmann E, Pattinson RC. Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy: 2019 National guideline. S Afr Med J. 2019 Sep 13;109(9):12723.

15. PMID: 34051884. Chappell LC, Cluver CA, Kingdom J, Tong S. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2021 Jul 24;398(10297):341-354. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32335-7. Epub 2021 May 27.

16. PMID: 19110215. Stella CL, Dacus J, Guzman E, Dhillon P, Coppage K, How H, Sibai B. The diagnostic dilemma of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura/hemolytic uremic syndrome in the obstetric triage and emergency department: lessons from 4 tertiary hospitals. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Apr;200(4):381.e1-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.10.037. Epub 2008 Dec 25.

17. PMID: 31761061. Jamieson DG, McVige JW. Imaging of Neurologic Disorders in Pregnancy. Neurol Clin. 2020 Feb;38(1):37-64. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2019.09.001.

18. PMID: 27831835. Kanekar S, Bennett S. Imaging of Neurologic Conditions in Pregnant Patients. Radiographics. 2016 Nov-Dec;36(7):2102-2122. doi: 10.1148/rg.2016150187.

19. PMID: 28190440. Wright WL. Neurologic complications in critically ill pregnant patients. Handb Clin Neurol. 2017;141:657-674. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63599-0.00035-1.

20. PMID: 30165588. van den Born BH, et al. ESC Council on hypertension position document on the management of hypertensive emergencies. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2019 Jan 1;5(1):37-46. doi: 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvy032. Erratum in: Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2019 Jan 1;5(1):46. doi: 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvy040.

21. PMID: 27708700. Anthony J, Schoeman LK. Fluid management in pre-eclampsia. Obstet Med. 2013 Sep;6(3):100-104. doi: 10.1177/1753495X13486896. Epub 2013 Jul 26.

22. PMID: 33861047. Bauer ME, et al. The Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology Interdisciplinary Consensus Statement on Neuraxial Procedures in Obstetric Patients With Thrombocytopenia. Anesth Analg. 2021 Jun 1;132(6):1531-1544. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000005355.

23. PMID: 26921648. Vaught AJ, et al. Direct evidence of complement activation in HELLP syndrome: A link to atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Exp Hematol. 2016 May;44(5):390-8. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2016.01.005. Epub 2016 Feb 26.

24. PMID: 23228435. Burwick RM, Feinberg BB. Eculizumab for the treatment of preeclampsia/HELLP syndrome. Placenta. 2013 Feb;34(2):201-3. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2012.11.014. Epub 2012 Dec 8.

Add comment