12 August 2020, by Shahriar Lahouti. Last update 1 July 2025.

CONTENTS

Preface

Circulatory dysfunction and poor organ perfusion serve as a major cause of organ injury and dysfunction. The backbone for understanding the pathophysiology and treatment plan for patients with organ dysfunction in view of poor systemic perfusion pressure is reviewed here.

Pathophysiology of Circulatory Failure

The circulation is a closed-loop system, operating at two levels, namely the macrocirculation and microcirculation. The former provides adequate perfusion pressure gradient through the organs, while the latter plays a pivotal role at the tissue level in the distribution of flow, supply of oxygen and nutrients, and elimination of waste products such as carbon dioxide.1

👉Effective tissue perfusion is the interplay of macro/microcirculation and cellular substrate utilization.

In a hypoperfusion state, oxygen supply to the tissues does not meet oxygen demand, and when acute and systemic in nature, it is called a shock state 2.

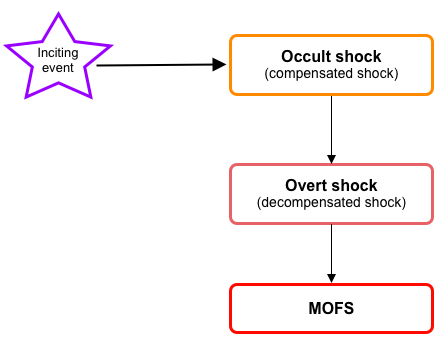

- During the initial evolution of the shock (compensated ~occult~impending shock), cellular injury is reversible; however, if left untreated, it progresses to the state of ‘overt shock’ in which irreversible cellular injury with multiple organ dysfunction/failure(MOFS) is inevitable (figure below).

Traditionally, shock has been classified based on systemic hemodynamic profile into hypovolemic, cardiogenic, extracardiac obstructive, and distributive, and this came to be accepted by most clinicians.3

Recent studies, alongside the advent of new technologies for direct assessment of tissue perfusion, have enlightened us to the intricacy of the pathophysiology of shock.4

- Shock is not a homogeneous disease process.

- The interplay of multiple parameters in between makes it variable in clinical presentation and outcome. Therefore, generalizing a “one-size-fits-all” approach to all situations may be inappropriate.

- Accordingly, a dynamic, granular, and individualized approach, integrating a more comprehensive pathophysiologic aspect of the disease, is deserved.5

The common final biochemical and metabolic pathway

Regardless of the physiologic/etiologic mechanism of the inciting event, if the hypoxic injury is extensive/prolonged, initiation of inflammatory cascades is the common pathophysiologic mechanism among all classes of shock.6

- This accounts for the fact that in practice, different classes of shock in later stages can not be differentiated well.5

Within the past few years, the focus of attention has shifted to the role of microcirculation in cellular hemostasis.

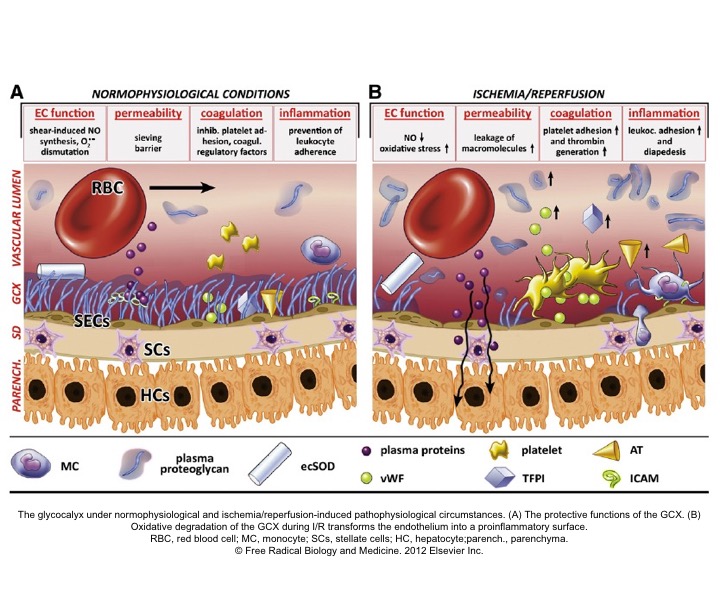

- Studies in sepsis 7 revealed that microcirculation is the key player in maintaining effective tissue perfusion. Healthy endothelial function and glycocalyx molecules are essential on the list.

- The Glycocalyx (GC) is a gel-like layer covering the luminal surface of vascular endothelial cells. It behaves as a sensor and mechano-transducer of the fluid shear forces and plays a key role in maintaining vascular permeability (fluid exchange), and modulation of adhesion of inflammatory cells and platelets to the endothelial surface.9

1# Loss of GC integrity

- The integrity of GC is disrupted in a wide range of pathologic states such as inflammation (e.g. sepsis), hypervolemia, hyperglycemia 10 as well as ischemia-reperfusion injury.

- Loss of GC results in increased vascular permeability (interstitial edema), activation of inflammatory, coagulation, and complement cascades; creating a state of dyshomeostasis which further potentiates the spiral of vicious cycle via ischemia, inflammation, and vasoplegia, culminating with the irreversible cellular injury.11

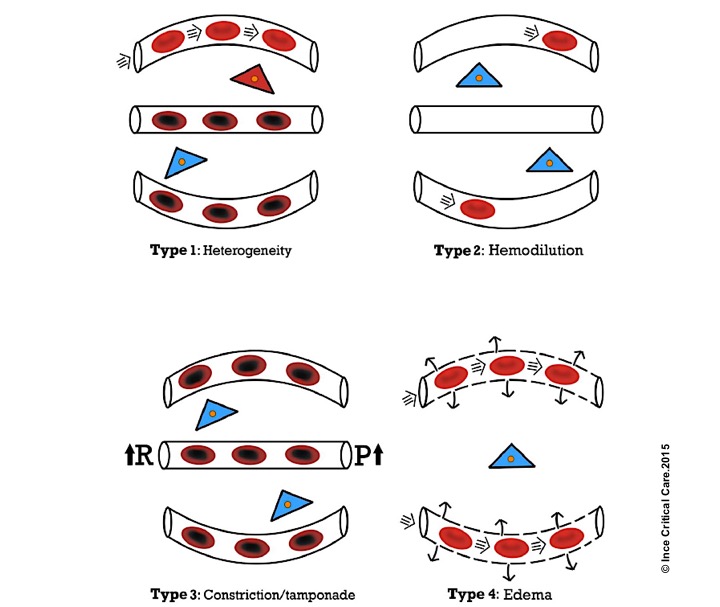

2# Loss of coherence between microcirculation and macrocirculation

- As these cascades of events progress, the coherence between the microcirculation and macrocirculation is lost, resulting in persistent tissue hypoperfusion despite improvement in macrocirculation following initial resuscitative efforts.

- In a recent article, four types of microcirculatory alteration in the state of inflammation and infection (which is common to all types of shock) were identified, where the hemodynamic coherence is lost 12 13

Microcirculatory alterations associated with loss of hemodynamic coherence. Microcirculatory alterations underlying the loss of hemodynamic coherence between the macrocirculation and the microcirculation resulting in tissue hypoxia. Type 1: heterogeneous perfusion of the microcirculation as seen in septic patients with obstructed capillaries next to perfused capillaries resulting in a heterogeneous oxygenation of the tissue cells. Type 2: hemodilution with the dilution of microcirculatory blood resulting in the loss of RBC-filled capillaries and increasing diffusion distance between RBCs in the capillaries and the tissue cells. Type 3: stasis of microcirculatory RBC flow induced by altered systemic variables (e.g. increased arterial vascular resistance (R) and or increased venous pressures causing tamponade. Type 4 alterations involve edema caused by capillary leak syndrome and which results in increased diffusive distance and reduced ability of the oxygen to reach the tissue cells. Red, well-oxygenated RBC and tissue cells; purple, RBC with reduced oxygenation; blue, reduced tissue cell oxygenation ©Crit Care.2015

This is arguably a game-changing finding in the treatment of the shock; however, it is still the tip of the iceberg, and more studies will clarify this murky issue.

- For many years, clinicians used systemic hemodynamic indices such as MAP and CVP as the therapeutic goal in the management of shock.

- However, we now know that optimizing systemic hemodynamic parameters may not necessarily result in the improvement of effective tissue perfusion.

Heterogeneity of shock

The heterogeneity of the shock has been explained at different levels.

Blood flow distribution

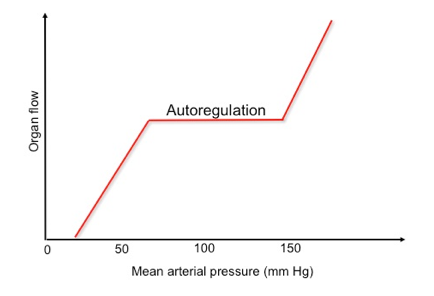

- At the organ/ tissue level, local distribution of blood flow is governed via two mechanisms: Intrinsic (autoregulation) and extrinsic regulation.

- Autoregulation

- The ability of all organ vascular beds to support normal blood flow is dependent on the maintenance of blood pressure within the defined range for that organ.

- Vital organs, such as the brain and myocardium, kidney, and liver have protective autoregulatory mechanisms with the brain and myocardium showing a wider autoregulatory capability, and the latter two having more limited autoregulatory capability (renal blood flow becomes pressure dependent below 60 mm Hg).

- Autoregulation

-

- Extrinsic mechanism

- This regulates the vascular tone at the basal state through RAAS (renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system)activity, while during physiologic stress, the autonomic nervous system predominates ( e.g., mottling and cold skin).

- Extrinsic mechanism

- As the perfusion pressure drops at the very beginning of the shock state, each vital organ tries to preserve perfusion pressure by an autoregulatory mechanism.

- 👉Heterogeneous flow to organs is present from the commencement of the shock.5

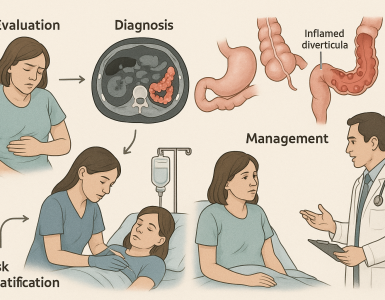

Physiologic type of inciting events

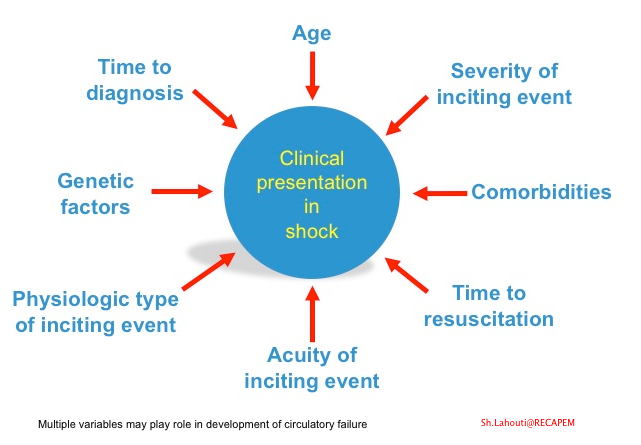

- Multiple factors account for the variable clinical presentation of the shock among the patients (figure below).

- Later on, in any shock state, the symptoms can be dominated (in different proportions) by the systemic inflammatory response, which adds complexity to the initial event.

- Therefore, clinical presentation varies depending on the time interval between recognition and resuscitation.5

Other factors

- There is also considerable heterogeneity in response to the mediators of cell injury on an individual basis. Multiple variables may play roles such as age, comorbidities, genetic factors, extent, severity, and type of precipitating circulatory insult (shown below).

The fact that each patient has a unique therapeutic response to the medication (fluid, vasopressors, inotropes, etc.) is perfectly explained above by the multifactorial nature of the disease. Moreover, as these multiple variables come into play at different time points in the course of the disease, a “one-size-fits-all” approach to all situations may be inappropriate.

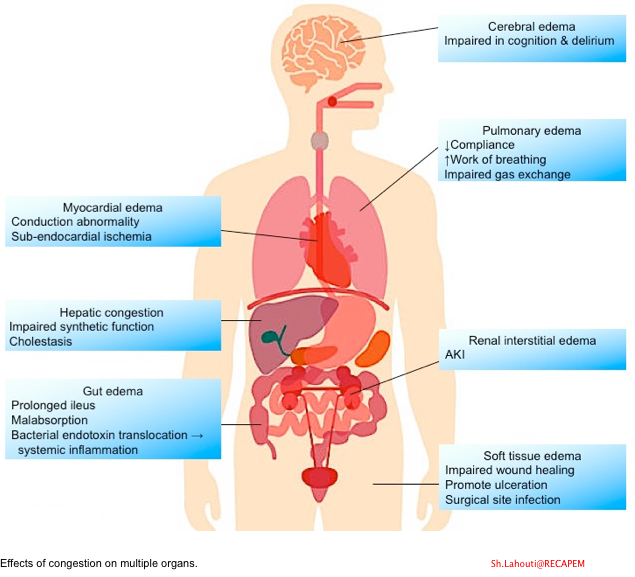

Organ congestion

It is of utmost importance to emphasize that protecting tissue perfusion is the cornerstone of resuscitation in a hypoperfusion state.

- However, it is worth mentioning that impaired tissue perfusion will also happen in other pathophysiologic processes such as venous congestion (volume overload) 14.

- The role of microvasculature and in particular GC molecules in maintaining cellular homeostasis have been explained above.

- Keep in mind that Intravascular congestion increases the CVP, thereby decreasing the perfusion pressure of vital organs (which is equal to the MAP minus the CVP)15.

- On the other hand, intravascular volume overload can cause GC degradation, which results in interstitial edema formation 16. This per se can cause tissue hypoxia (↑diffusive distance).

- The impact of congestion on various organs is shown below 17.

General Principles of Diagnosis and Management

⭐️Time is Tissue

- Several studies have shown that early identification and institution of appropriate resuscitative measures can prevent progressive inflammatory cascades and improve the outcome in patients with systemic circulatory failure (i.e., shock) or congestive organ dysfunction.

⚠️Diagnostic challenges and pitfalls

- Unfortunately, during the compensatory stage of the disease process, when identifying the shock state is critically important in terms of outcome, it is so challenging to diagnose since all macrocirculatory indices may look within normal range (e.g., normal MAP, CVP, etc.).

- On the other hand, there’s a huge list of differential diagnoses for each possible presenting sign and symptom. For example, the differential diagnosis of delirium is exemplified below:

| Differential diagnosis of delirium 👉Brain disorder: Encephalitis, non-convulsive status epilepticus, head injury, hypertensive encephalopathy, psychiatric disorder 👉Metabolic: Electrolyte disturbances, ↑↓PaCO2, ↑↓PaO2, ↑↓glucose, ↑↓Serum osmolarity, ↑↓(thyroid, parathyroid, adrenal, pituitary gland) 👉Drug and toxin: Anticholinergic, anticonvulsant, antidepressant, hypoglycemic agents, sedatives, toxic alcohol, etc. 👉Systemic organ failure 👉Infections: Sepsis, Fever-related delirium 👉Physical disorders: Hyperthermia, hypothermia, trauma with SIRS, fat embolism, head injury |

- No symptom, sign, or lab/imaging feature is sensitive or specific enough to make the diagnosis.

- Adding more to the complexity (as previously said), all types of shock can share the state of inflammation and vasoplegia in their evolution, and oftentimes shock is multifactorial in practice (e.g., cardiogenic plus sepsis) 18.

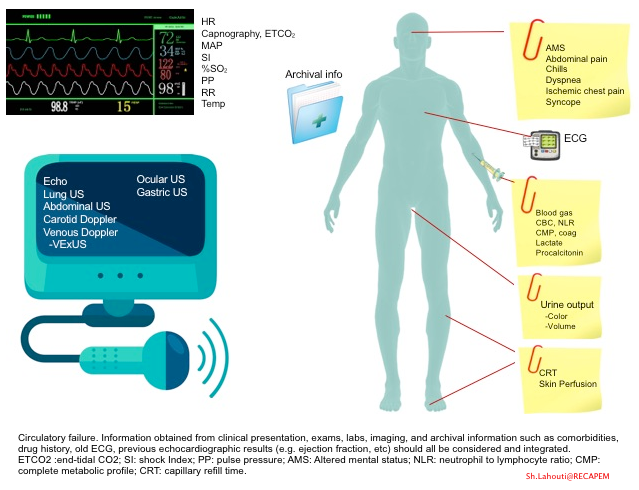

Principles of diagnosis

- Diagnosis of circulatory failure deserves a holistic and integrative approach in an appropriate clinical context.

- The information obtained from clinical presentation, exams, labs, imaging, and archival information such as comorbidities, drug history, old ECG, and previous echocardiographic results (e.g., ejection fraction, etc.) should all be considered and integrated.

- The approach to unstable patients and the integration of the above parameters are discussed separately.

- Keep in mind that in the absence of widely available devices that directly measure tissue perfusion, clinical surrogates of tissue perfusion, such as skin perfusion status, urine output, change in mental status, and serum lactate, are commonly used. More on this, here.

- More on serum lactate, here.

Point of care ultrasound

- The use of ultrasound in emergency departments and critical care units is revolutionizing the diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring of patients in shock states.

- Several protocolized ultrasonographic examinations have been described, including Rapid Ultrasound in Shock(RUSH)21, Abdominal and Cardiac Evaluation in Shock (ACES)22, among others, for evaluation of patients in shock state.

- However, a more thorough approach would be to perform a complete examination and then compare it to patterns expected for various types of shock. This cognitive approach may facilitate the diagnosis of multifactorial shock, which will often defy simple categorization.

- Other protocolized ultrasonographic examinations have been suggested for the use of ultrasound during different situations, namely the use of ultrasound during cardiac arrest (e.g., CASA, CAUSE)23 24. (This will be discussed separately.)

- For example, using POCUS in patients with cardiac arrest can be helpful to differentiate asystole from fine ventricular fibrillation, both of which may look the same on ECG (see video below).

- The presence of subtle disorganized cardiac twitching is consistent with ventricular fibrillation.

- For example, using POCUS in patients with cardiac arrest can be helpful to differentiate asystole from fine ventricular fibrillation, both of which may look the same on ECG (see video below).

POCUS: Caveats

- However, like other diagnostic modalities, ultrasound has its caveats. Right?

- It is true that a complete evaluation by ultrasound/echo gives us almost the whole story. The caveat here is that you must know a whole lot about ultrasound; otherwise, it misleads you!

- The Prometheus analogy is ‘A little information is a child playing with fire’.

| Diffuse bilateral B-lines are visualized on lung ultrasound in the following clip. Does this suggest intravascular volume overload? |

- Congestion is defined at two levels:

- Hemodynamic congestion refers to the state of volume overload resulting in increased left ventricular filling pressure.

- Clinical congestion refers to the constellation of signs and symptoms that result from increased left ventricular filling pressure.25

- Oftentimes, hemodynamic congestion precedes clinical congestion.

- Organ congestion could be due to volume overload or altered Starling forces, such as ↑permeability, ↓and intravascular oncotic pressure, which happens when endothelial barriers or GC molecules are disrupted.

- B-lines:

- Visualization of pathologic B-lines signifies the presence of a density (pus, serum, blood, fibrotic tissue, etc.) within the lung interstitium.

- Diffuse B-lines have a better correlation with extravascular lung water(EVLW), which is the amount of water contained in the lung outside the pulmonary vasculature, than with the increased left atrial pressure.

- The differential diagnosis for diffuse B-lines includes:

-

- Cardiogenic pulmonary edema (CPE)

- Non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema(NCPE)

- Interstitial lung disease(ILD)

- B-lines are present in ‘ILD’ (dry B-lines), and often differentiation with wet B-lines (in CPE, NCPE) can only be made in the appropriate clinical context.

- By and large, the presence of B-lines is highly indicative of increased EVLW, which could be caused by NCPE or CPE.26

- In NCPE, organ congestion is present due to altered permeability of vasculature, despite that systemic congestion may be absent.

- However, in CPE, organ congestion is caused by volume/pressure overload. Here, volume restriction, decongestion strategy, and afterload reduction are deployed.

- Pleural line irregularity:

- In differentiating CPE from NCPE, it has been reported in several studies that in the presence of ‘lung sliding, regular pleural line, and absence of subpleural consolidation’; the diagnosis will fall in favor of CPE, with B-lines alone; it is not always possible to separate EVLW accumulation due to heart failure or acute respiratory distress syndrome, therefore LUS should be supported with other modalities such as echocardiogram.27 28

- Keep in mind that acute heart failure is not even a single disorder; rather, multiple phenotypes with different pathophysiologic alterations exist(1).

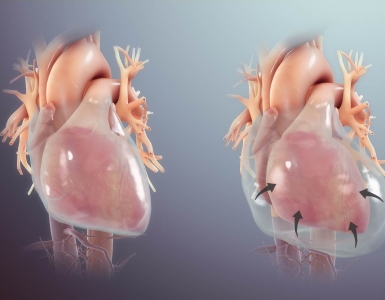

A 50-year-old male patient with a diagnosis of septic shock (retrospectively) has been resuscitated appropriately by vasopressor (NE @ 10mcg/min without wide fluctuation in dose), a fluid bolus, and antibiotics following which his sensorium improved, MAP increased to 60 mm Hg, and his urine output within 2h remarkably increased. Skin mottling disappeared. The following echo (on the left) belongs to his initial presentation, and (on the right) to post-resuscitation. Does this finding suggest treatment failure?

The post-resuscitation echo shows a worsened EF eyebally. However, it does not suggest treatment failure since his clinical indicators of perfusion are improved.

The vasoplegia in sepsis poses low systemic vascular resistance, and almost any heart (even the one with poor contractility) can perform better under this low afterload milieu. Following the institution of vasopressor, the systemic vascular resistance is restored, and the likely preexisting poor contractility is uncovered 29

Another patient with a diagnosis of septic shock (retrospectively) has been resuscitated with 2L of crystalloid fluid, antibiotics, and vasopressor (NE @ 10mcg/min). Following the resuscitation, his MAP is 50 mm Hg, mental status is altered, and there is unremarkable urine output within 2h. Ultrasound of the IVC following the resuscitation is shown below. Are further fluid boluses deserved?

Complete collapse of the IVC during inspiration ( both walls nearly touching) does not imply volume depletion 30

- In vasoplegic conditions, Intravascular volume extravasates into the interstitium; moreover, venous dilation decreases the venous stressed volume and may also increase venous capacitance, all of which result in reduced venous return.31

- In such conditions, the IVC may appear empty with collapsibility of > 70% during inspiration in the US exam, but this does not justify the administration of further fluid. In fact, the microvascular permeability is altered, and it will not keep fluid intravascularly anymore! 32

The Goal of Resuscitation

The treatment goal in the hypoperfusion state (systemic and or regional) is to normalize cellular respiration.33 As explained above, improving systemic hemodynamic metrics (e.g., MAP) does not necessarily correlate to improvement in tissue perfusion and organ function.34

Moreover, shock is a heterogeneous disease, and different treatment approaches may be warranted at different times in the same patient.

Despite that the microcirculatory role has been brought to the fore recently, since the specific end organ tissue perfusion and oxygen utilization are difficult to measure thus far; surrogate systemic cardiovascular metrics are used in their place.35

- More on resuscitative end-points, 👉here.

- For principles of resuscitation of patients in a shock state, see 👉here.

- Principles of management of patients with hypervolemia and congestion are discussed 👉here.

Hemodynamic monitoring

The goal of hemodynamic monitoring is to guide our medical management so as to prevent or treat organ failure and improve the outcomes of our patients.

- What matters in hemodynamic monitoring is to understand the pathophysiology of the disease entities and appropriate integration of hemodynamic variables in a clinical context and with respect to cardiovascular physiology, since we treat the patients but not the numbers!36

- No static variables can measure the hemodynamic response to the treatment and therefore have no diagnostic guidance value.

- The dynamic variables include: Assessing responsiveness to fluid, vasopressor, and inotrope (more on this,👉 here).

Note (1): Acute heart failure is often considered a homogenous disorder caused by volume overload. In acute flash pulmonary edema (aka. Sympathetic Crashing Acute Pulmonary Edema ‘SCAPE’}, the pathophysiologic insult is increased afterload and decreased venous capacitance secondary to a catecholamine surge (most commonly nonadherence to diet and medications in patients with a history of hypertension). This results in volume redistribution from the peripheral vascular bed into the ‘central compartment’ (pulmonary circulation), causing central congestion. These patients do not have volume overload despite the plump IVC in ultrasonography. They often have volume deficits and are dehydrated. The response to diuretics is poor, and the treatment of choice for such patients is afterload reducers.39

References

1. Guven, G., Hilty, M. P., & Ince, C. (2020). Microcirculation: Physiology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Application. Blood Purification, 49(1–2), 143–150. https://doi.org/10.1159/000503775

2. Vincent JL, De Backer D. Circulatory shock. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(18):1726-1734. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1208943(Z)Hasanin, A., Mukhtar, A., & Nassar, H. (2017). Perfusion indices revisited. Journal of Intensive Care, 5(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-017-0220-5

3. Cecconi, M., De Backer, D., Antonelli, M. et al. Consensus on circulatory shock and hemodynamic monitoring. Task force of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med 40, 1795–1815 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-014-3525-z

4. Donati, A., Domizi, R., Damiani, E., Adrario, E., Pelaia, P., & Ince, C. (2013). From macrohemodynamic to the microcirculation. Critical Care Research and Practice, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/892710

5. Squara, P., Hollenberg, S., & Payen, D. (2019). Reconsidering Vasopressors for Cardiogenic Shock: Everything Should Be Made as Simple as Possible, but Not Simpler. Chest, 156(2), 392–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2019.03.020

6. Lim HS. Cardiogenic Shock: Failure of Oxygen Delivery and Oxygen Utilization. Clin Cardiol. 2016;39(8):477-483. doi:10.1002/clc.22564

7. Spronk, P. E., Zandstra, D. F., & Ince, C. (2004). Bench-to-bedside review: Sepsis is a disease of the microcirculation. Critical Care, 8(6), 462–468. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc2894

8. Chang, J.C. Sepsis and septic shock: endothelial molecular pathogenesis associated with vascular microthrombotic disease. Thrombosis J 17, 10 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12959-019-0198-4

9. Dogné, S., & Flamion, B. (2020). Endothelial Glycocalyx Impairment in Disease: Focus on Hyaluronan Shedding. American Journal of Pathology, 190(4), 768–780. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2019.11.016

10. Yilmaz, O., Afsar, B., Ortiz, A., & Kanbay, M. (2019). The role of endothelial glycocalyx in health and disease. Clinical Kidney Journal, 12(5), 611–619. https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sfz042

11. van Golen RF, van Gulik TM, Heger M. Mechanistic overview of reactive species-induced degradation of the endothelial glycocalyx during hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52(8):1382-1402. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.01.013

Ince, C. (2015). Hemodynamic coherence and the rationale for monitoring the microcirculation. Critical Care, 19(Suppl 3), S8. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc14726

12. Kara A, Akin S, Ince C. Monitoring microcirculation in critical illness. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2016;22(5):444-452. doi:10.1097/MCC.0000000000000335

13. Hasanin, A., Mukhtar, A. & Nassar, H. Perfusion indices revisited. j intensive care 5, 24 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-017-0220-5

14. Beaubien-Souligny W, Bouchard J, Desjardins G, et al. Extracardiac Signs of Fluid Overload in the Critically Ill Cardiac Patient: A Focused Evaluation Using Bedside Ultrasound. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33(1):88-100. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2016.08.012

15. Prowle, J. R., Echeverri, J. E., Ligabo, E. V., Ronco, C., & Bellomo, R. (2010). Fluid balance and acute kidney injury. Nature Reviews Nephrology, 6(2), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneph.2009.213

16. O’Connor, M. E., & Prowle, J. R. (2015). Fluid Overload. Critical Care Clinics, 31(4), 803–821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccc.2015.06.013

Lambden, S., Creagh-Brown, B.C., Hunt, J. et al. Definitions and pathophysiology of vasoplegic shock. Crit Care 22, 174 (2018).https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-018-2102-1

17. Hernández G, Ospina-Tascón GA, Damiani LP, et al. Effect of a Resuscitation Strategy Targeting Peripheral Perfusion Status vs Serum Lactate Levels on 28-Day Mortality Among Patients With Septic Shock: The ANDROMEDA-SHOCK Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019;321(7):654-664. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.0071

18. Ait-Oufella H, Bourcier S, Alves M, et al. Alteration of skin perfusion in mottling area during septic shock. Ann Intensive Care. 2013;3(1):31. Published 2013 Sep 16. doi:10.1186/2110-5820-3-31

19. Seif D, Perera P, Mailhot T, Riley D, Mandavia D. Bedside ultrasound in resuscitation and the rapid ultrasound in shock protocol. Crit Care Res Pract. 2012;2012:503254. doi:10.1155/2012/503254

20. Atkinson PR, McAuley DJ, Kendall RJ, et al. Abdominal and Cardiac Evaluation with Sonography in Shock (ACES): an approach by emergency physicians for the use of ultrasound in patients with undifferentiated hypotension. Emerg Med J. 2009;26(2):87-91. doi:10.1136/emj.2007.056242

21. Gardner KF, Clattenburg EJ, Wroe P, Singh A, Mantuani D, Nagdev A. The Cardiac Arrest Sonographic Assessment (CASA) exam – A standardized approach to the use of ultrasound in PEA. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(4):729-731. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2017.08.052

22. Hernandez C, Shuler K, Hannan H, Sonyika C, Likourezos A, Marshall J. C.A.U.S.E.: Cardiac arrest ultrasound exam–a better approach to managing patients in primary non-arrhythmogenic cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2008;76(2):198-206. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.06.033

23. Gheorghiade M, Filippatos G, De Luca L, Burnett J. Congestion in acute heart failure syndromes: an essential target of evaluation and treatment. Am J Med. 2006;119(12 Suppl 1):S3-S10. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.09.011

24. Bataille B, Rao G, Cocquet P, et al. Accuracy of ultrasound B-lines score and E/Ea ratio to estimate extravascular lung water and its variations in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Clin Monit Comput. 2015;29(1):169-176. doi:10.1007/s10877-014-9582-6

25. Blanco PA, Cianciulli TF. Pulmonary Edema Assessed by Ultrasound: Impact in Cardiology and Intensive Care Practice. Echocardiography. 2016;33(5):778-787. doi:10.1111/echo.13182

26. Picano E, Pellikka PA. Ultrasound of extravascular lung water: a new standard for pulmonary congestion. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(27):2097-2104. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehw164

27. Griffee MJ, Merkel MJ, Wei KS. The role of echocardiography in hemodynamic assessment of septic shock. Crit Care Clin. 2010;26(2):. doi:10.1016/j.ccc.2010.01.001

28. Vegas A, Denault A, Royse C. A bedside clinical and ultrasound-based approach to hemodynamic instability – Part II: bedside ultrasound in hemodynamic shock: continuing professional development. Can J Anaesth. 2014;61(11):1008-1027. doi:10.1007/s12630-014-0231-9

29. Denault A, Vegas A, Royse C. Bedside clinical and ultrasound-based approaches to the management of hemodynamic instability–part I: focus on the clinical approach: continuing professional development. Can J Anaesth. 2014;61(9):843-864. doi:10.1007/s12630-014-0203-

30. De Backer, D., Cortes, D. O., Donadello, K., & Vincent, J. L. (2014). Pathophysiology of microcirculatory dysfunction and the pathogenesis of septic shock. Virulence, 5(1), 73–79. https://doi.org/10.4161/viru.26482

31. Gidwani H, Gómez H. The crashing patient: hemodynamic collapse. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2017;23(6):533-540. doi:10.1097/MCC.0000000000000451

32. Ochagavía A, Baigorri F, Mesquida J, et al. Monitorización hemodinámica en el paciente crítico. Recomendaciones del Grupo de Trabajo de Cuidados Intensivos Cardiológicos y RCP de la Sociedad Española de Medicina Intensiva, Crítica y Unidades Coronarias [Hemodynamic monitoring in the critically patient. Recommendations of the Cardiological Intensive Care and CPR Working Group of the Spanish Society of Intensive Care and Coronary Units]. Med Intensiva. 2014;38(3):154-169. doi:10.1016/j.medin.2013.10.006

33. Vincent JL, Rhodes A, Perel A, et al. Clinical review: Update on hemodynamic monitoring–a consensus of 16. Crit Care. 2011;15(4):229. Published 2011 Aug 18. doi:10.1186/cc10291

34. Bartlett, R. H. (1995). Alice in intensiveland: Being an essay on nonsense and common sense in the ICU, after the manner of Lewis Carroll. Chest, 108(4), 1129–1139. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.108.4.1129

35. Hadian M, Pinsky MR. Functional hemodynamic monitoring. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2007;13(3):318-323. doi:10.1097/MCC.0b013e32811e14dd

36. Kenaan M, Gajera M, Goonewardena SN. Hemodynamic assessment in the contemporary intensive care unit: a review of circulatory monitoring devices. Crit Care Clin. 2014;30(3):413-445. doi:10.1016/j.ccc.2014.03.007

37. Viau DM, Sala-Mercado JA, Spranger MD, O’Leary DS, Levy PD. The pathophysiology of hypertensive acute heart failure. Heart. 2015;101(23):1861-1867. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2015-307461

Add comment