8 May 2025, by Shahriar Lahouti. Peer reviewed by Abdolghder Pakniyat.

CONTENTS

- Preface

- Practical aspect

- ECG Evaluation: Diagnosing The Rhythm

- Conduction system anatomy

- Mechanism and subtypes of bradycardia

- Analysis of ECG in bradycardia

- Sinus node dysfunction

- Heart Block: Key Points

- Escape rhythms

- Atrial fibrillation or flutter with slow ventricular response

- Group beating

- Table summary: ECG findings

- Failure of a previously implanted pacemaker device

- Background

- Implant-related complications

- Pacemaker malfunction

- General Approach and Management of Critical Patients with PM Malfunction

- Specific types of device malfunction

- Infogram

- References

Preface

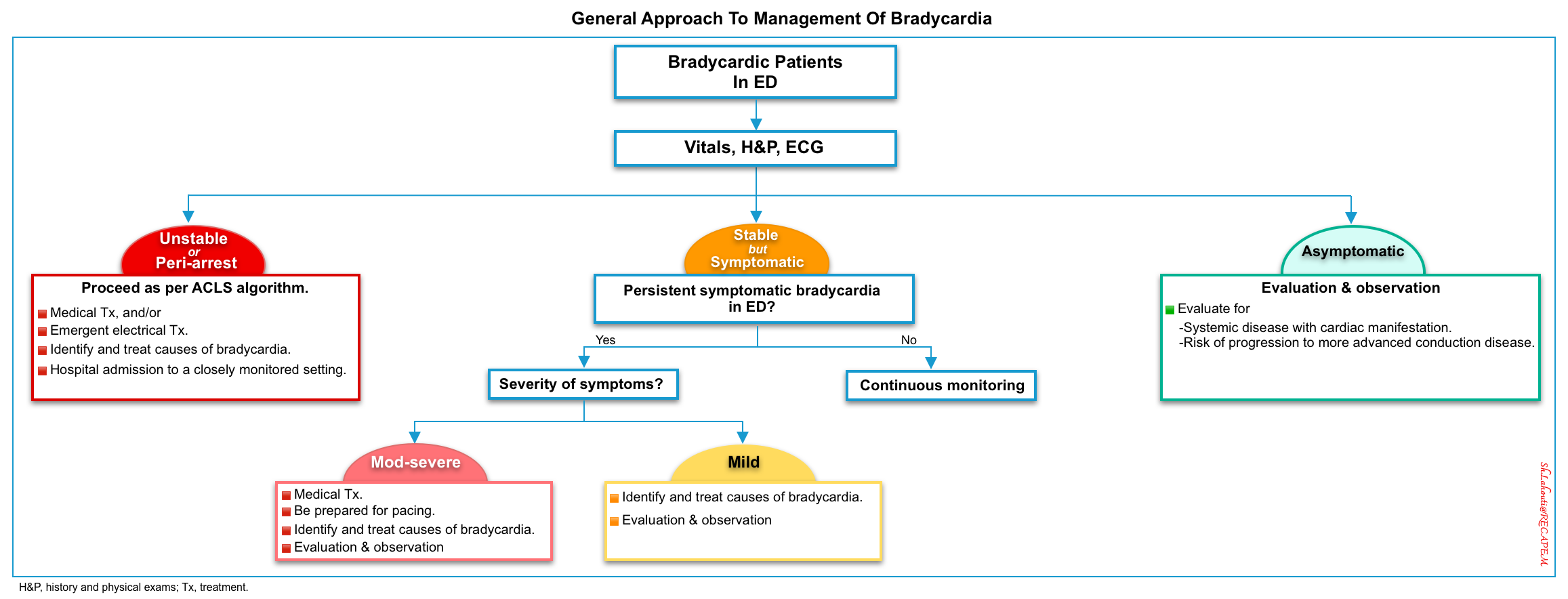

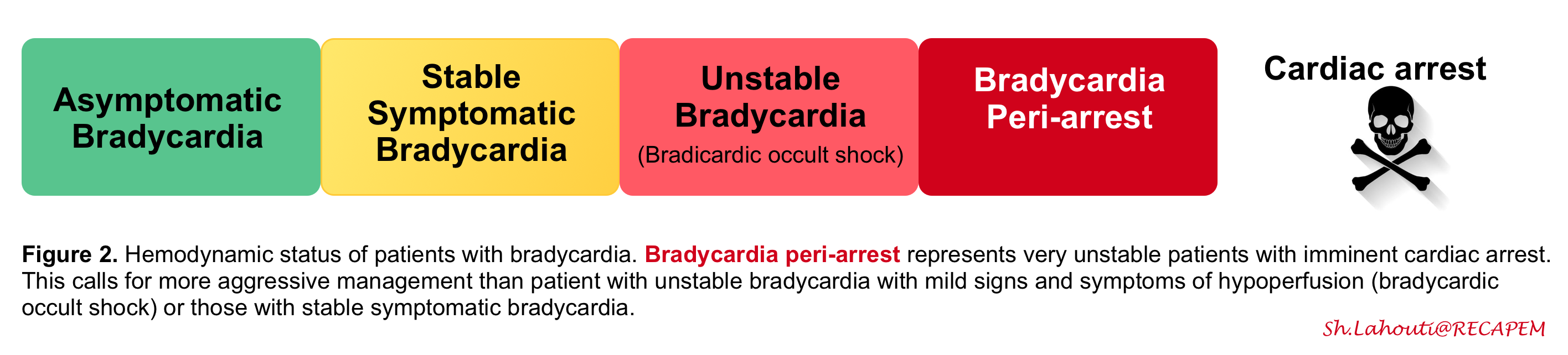

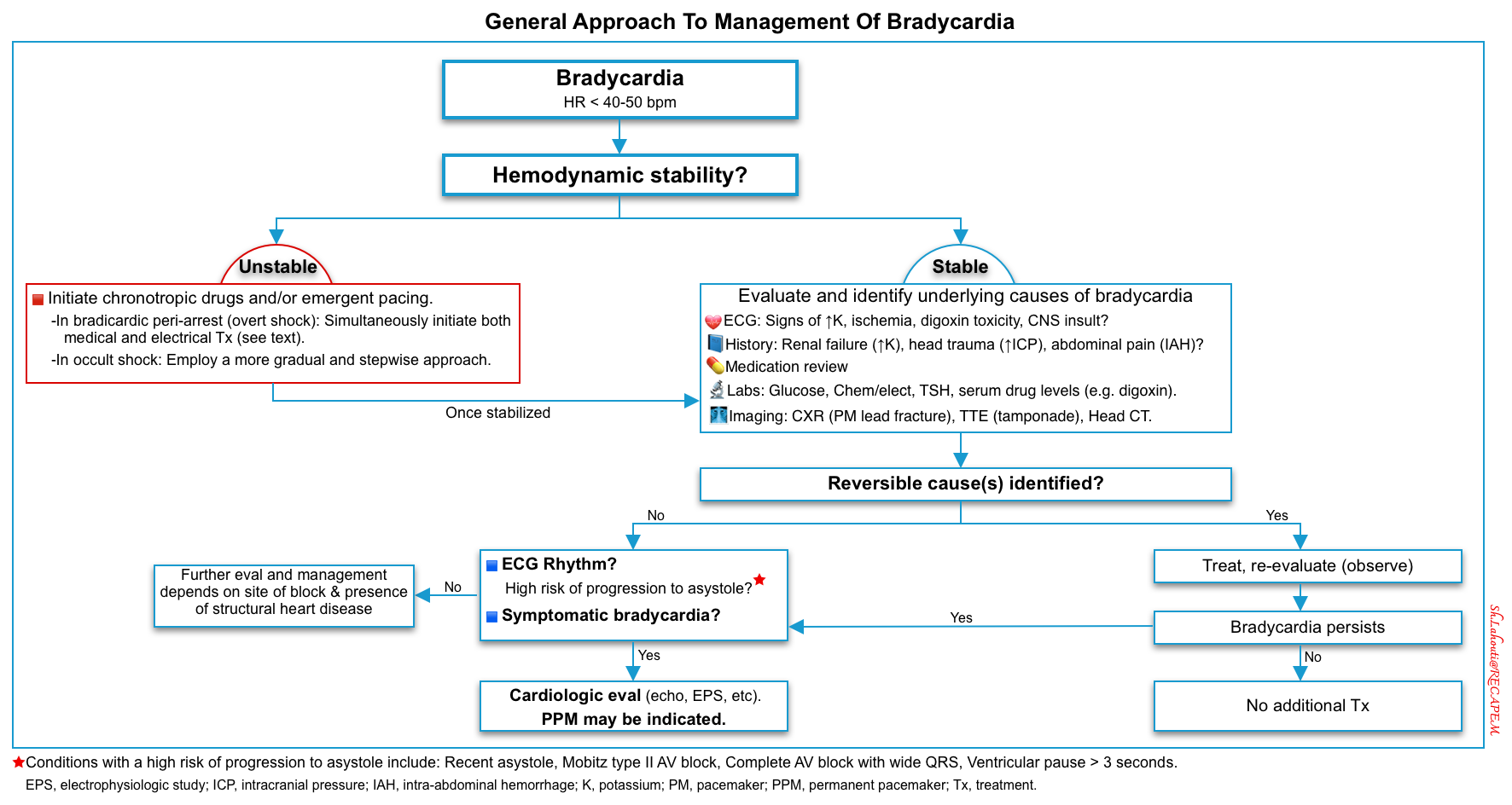

Bradycardia, also known as bradyarrhythmia, has traditionally been defined by consensus as a slow heart rate (HR) of less than 50-60 beats per minute. Based on “hemodynamic stability“, patients with bradycardia should be approached first in the emergency department.

Patients with unstable bradycardia require emergent temporizing treatments with an external pacemaker, atropine, and/or adrenergic drugs to increase the heart rate until the underlying cause is identified and treated (figure below). The clinical approach to evaluating and managing “unstable bradycardia” has been discussed previously here 📖.

Bradycardia happens through several electrophysiologic mechanisms, resulting in different rhythms with a slow ventricular rate. Differentiating the bradycardic rhythms could be challenging and time-consuming. As already emphasized, the emergency physician should initially focus on the hemodynamic stability of the patients (rather than diagnosing the rhythm).

This post will provide an overview of the evaluation and general management of bradycardia, focusing on different subtypes of bradycardic rhythms and their clinical significance.

Practical aspect

Clinical manifestation

◾️Clinical significance of bradycardia

- Bradycardia can directly pull down cardiac output and cause hemodynamic instability (more on this here).

- Cardiac output = Heart rate x stroke volume.

- When a low heart rate is no longer compensated by increases in stroke volume, the cardiac output decreases, causing symptoms *.

- Tolerance for bradyarrhythmias is largely dictated by the patient’s ability to augment cardiac output in response to the decreased heart rate.

- Cardiac output = Heart rate x stroke volume.

- In addition, very slow rates due to AV heart block can induce QT interval prolongation with torsades de pointes ventricular tachycardia.

◾️Clinical manifestations of bradycardia can range from asymptomatic to impending cardiac arrest (Figure 2).

◾️Clinical presentation:

- Asymptomatic

- Mild to moderate bradycardia is frequently asymptomatic.

- Angina, acute ischemia on ECG (myocardial ischemia).

- Exertional dyspnea and fatigue (due to inability to augment heart rate and cardiac output with exercise).

- Shortness of breath (pulmonary congestion).

- Presyncope/syncope and lightheadedness.

- Shock.

- Defined as a myriad of hypotension and signs and symptoms of poor organ perfusion, including altered mental status, ischemic chest pain, and dyspnea from acute heart failure *. Note that patients in a shock state may present with different clinical manifestations:

- Occult (normotensive) bradycardic shock.

- In some patients with adequate physiologic reserve, compensatory vasoconstrictor response may maintain blood pressure and mental status despite the low cardiac output and poor organ perfusion (remember that BP is not equal to cardiac output).

- They require monitoring and urgent therapy, but they are not actively dying!

- Overt bradycardic shock (aka bradycardic peri-arrest, impending cardiac arrest).

- It refers to severe hemodynamic derangement with low blood pressure and organ malfunction.

- These patients have worsening symptoms and deteriorating vital signs (e.g, HR< 30 bpm or progressively worsening bradycardia) with imminent threat of cardiac arrest. Hence, emergent resuscitation is warranted for these patients, The term bradycardic peri-arrest is a better term used for such a condition (aka impending cardiac arrest).

- Occult (normotensive) bradycardic shock.

- Defined as a myriad of hypotension and signs and symptoms of poor organ perfusion, including altered mental status, ischemic chest pain, and dyspnea from acute heart failure *. Note that patients in a shock state may present with different clinical manifestations:

- Sudden cardiac arrest.

- Cannon A wave occurs when the right atrium contracts against a closed tricuspid valve, and can be seen occasionally in the jugular vein (video below).

- This can be seen in atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia, complete heart block, and ventricular tachycardia *.

Etiology

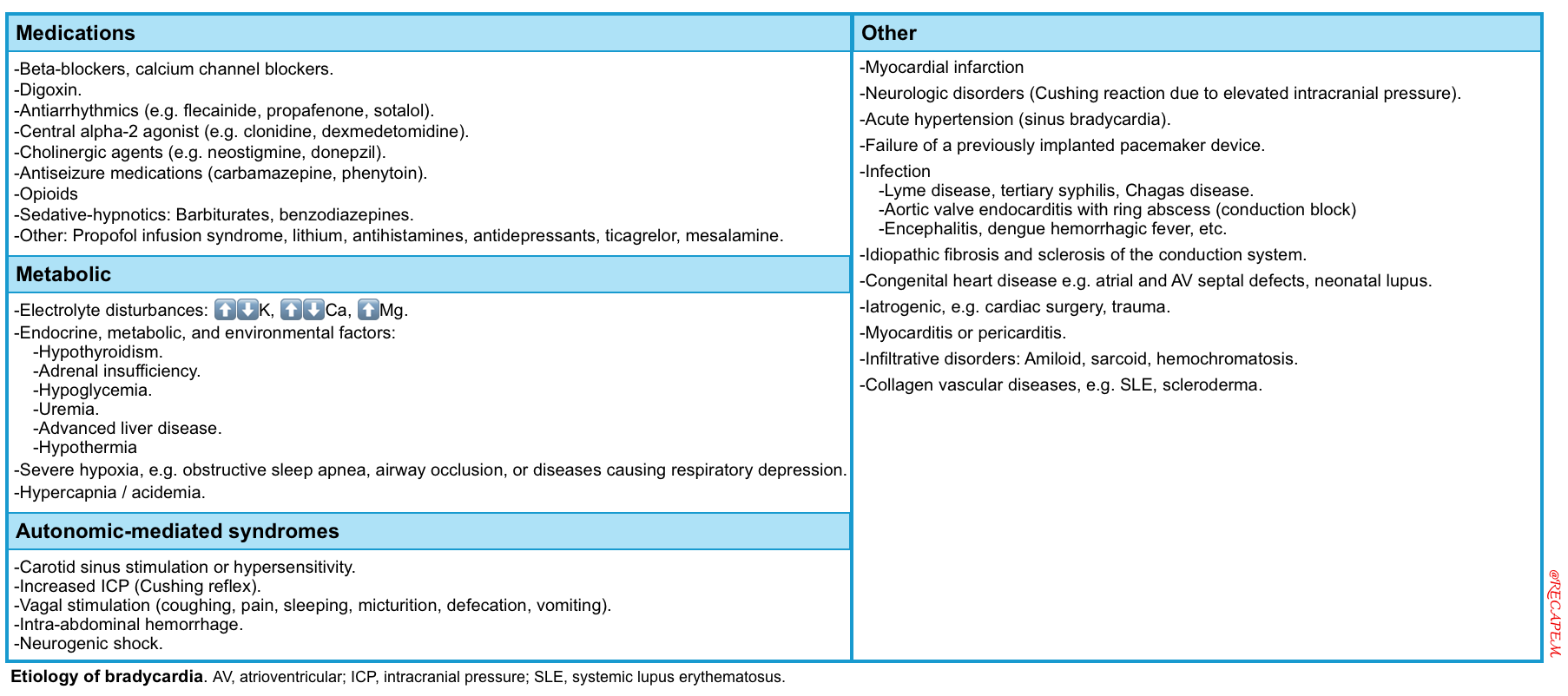

- Causes of bradycardia can be reversible or irreversible *. The common causes of bradydysrhythmias are summarized in the following table.

- Reversible causes: Medications (e.g., β-blockers, digoxin), electrolyte disturbances (e.g., hyperkalemia), BRASH Syndrome, inflammatory processes (e.g., myocarditis), acute myocardial infarction (especially inferior MI), and ↑vagal tone *.

- Irreversible causes with permanent damage: Some other factors may cause permanent damage to the conduction system, such as infiltrative diseases of the heart (e.g., amyloid), degeneration of the conduction system (usually with advanced age).

Note: Failure of a previously implanted pacemaker device will be discussed here.

General Evaluation

◾️History

- Medication list (see here), recent change in home medications, dose titration, eye drops with sympatholytic effects *

- Renally cleared meds plus acute kidney injury.

- Obtaining a relevant history will assist in discovering the underlying etiology of the patient’s bradycardia *:

- A history of “Renal Failure or Dialysis” is suggestive of “Hyperkalemia”. See BRASH Syndrome.

- A history of “Ischemic Chest Pain” may suggest “Myocardial Infarction”.

- Recent “Head trauma, Headache, and Altered mentation” may suggest Elevated ICP (e.g., ICH, SAH).

- “Blunt trauma, Abdominal pain/distention, Pregnancy (ectopic)” may suggest “Intra-abdominal Hemorrhage”.

- Cold intolerance, Weight gain, and ↑Fatigue may suggest Hypothyroidism.

- In patients with “Cardiac Surgery”, consider surgical “Structural Damage and Congenital Heart Disease”.

- Fevers, Travel, ticks, and Unprotected sex can suggest “Infectious Etiologies” (Lyme, myocarditis, syphilis, tuberculosis).

◾️Physical exam (The exam can also guide in identifying the underlying etiology).

- 🫀Hemodynamic stability should be assessed first, and adequacy of perfusion should be confirmed.

- Blood pressure, shock index, mental status, skin perfusion status)

- 🌡️Obtain a core temperature, if “Hypothermia” is suspected (rectal is preferable).

- Bradycardia due to hypothermia will not respond well to electrical impulses or atropine. In fact, pacing may be harmful because the cold cardiac membrane is unstable in hypothermia and prone to refractory ventricular fibrillation *.

- 🧠Neuro/toxicologic exam

- Evidence of elevated intracranial pressure (e.g., stupor, widened optic nerve sheath in ocular ultrasound)?

- Patients with bradycardia can be drowsy or confused solely based on decreased cardiac output.

- 💡However, when mental status is disproportionately depressed for a given heart rate (e.g., GCS 8 in a patient with HR 45 bpm), one should consider neurologic causes of bradycardia with ↑ICP and drug overdose.

- Patients with bradycardia can be drowsy or confused solely based on decreased cardiac output.

- Pinpoint pupils may suggest toxic ingestion (e.g, clonidine or cholinergic agent).

- Evidence of elevated intracranial pressure (e.g., stupor, widened optic nerve sheath in ocular ultrasound)?

- Look for a dialysis catheter or fistula.

- Evidence of trauma (head or abdominal).

◾️Bedside US: Cardiopulmonary and abdominal exam

- Volume status?

- Evidence of pulmonary congestion (e.g, B-lines throughout the lung fields)?

- Intra-abdominal free fluid?

- Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) is a level-one recommendation of the AHA/ACC/HRS for patients who are bradycardic and have the following *:

- Newly identified left bundle branch block.

- Second-degree Mobitz type II AV block.

- High-grade AV block.

- Third-degree AV block with or without apparent structural heart disease or coronary artery disease.

- TTE should also be part of the initial evaluation in patients whose symptoms are suspected to be cardiac in origin (e.g., MI, structural disease).

- Evidence of myocardial infarction (e.g., Inferior Wall Motion Abnormality)?

- Evidence of valvular heart disease?

- TTE can also assist with determining appropriate pacemaker capture *.

◾️ECG. Focus on the following:

- Signs of hyperkalemia (e.g, peaked T-waves, prolonged PR interval).

- Signs of ischemia, especially inferior MI.

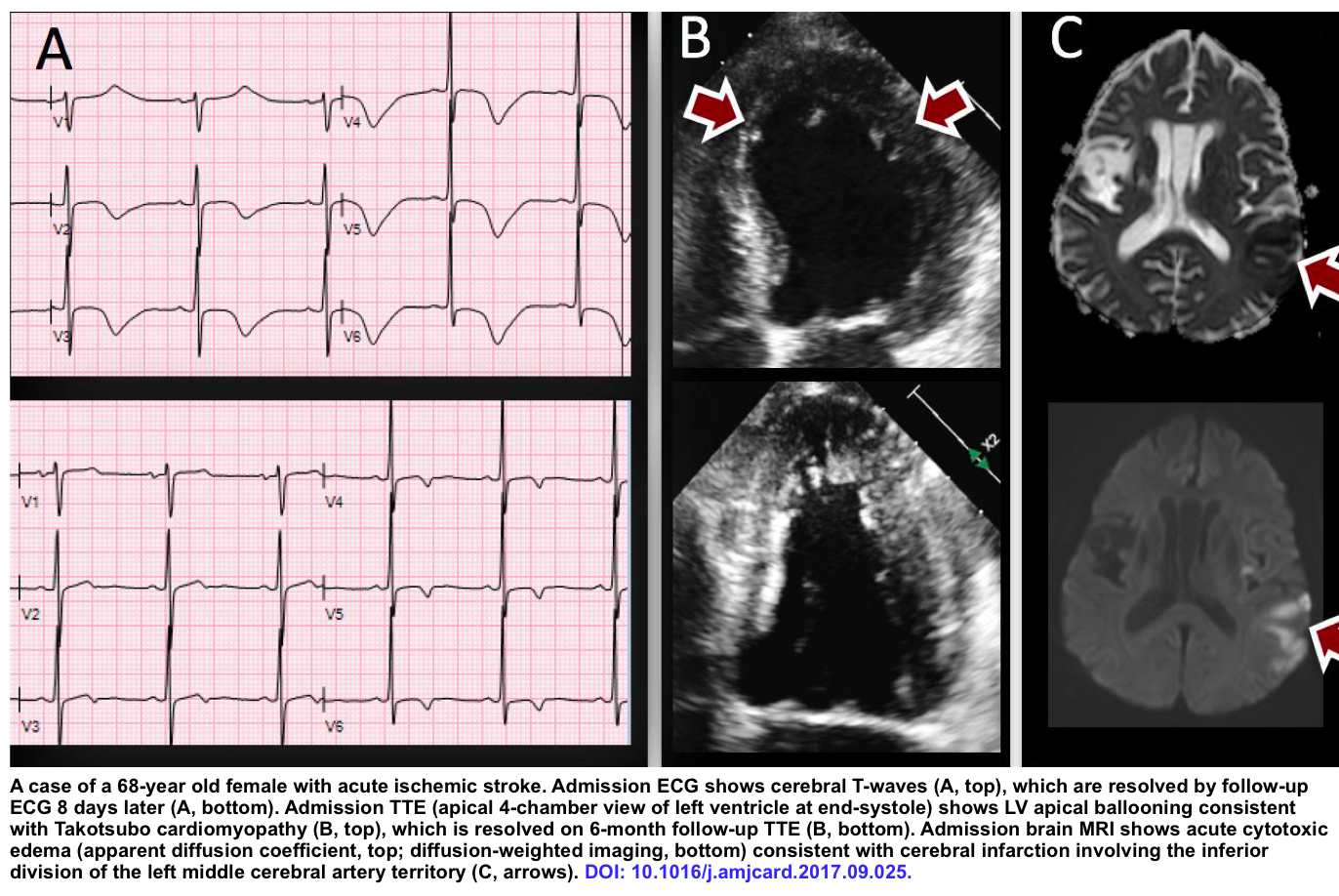

- Deep symmetric TWI (cerebral TWI) in anterior leads may suggest neurologic insults, e.g, ischemic stroke, subarachnoid hemorrhage.

- Cerebral TWI is defined as T-wave inversion of ≥5 mm depth in ≥4 contiguous precordial leads *

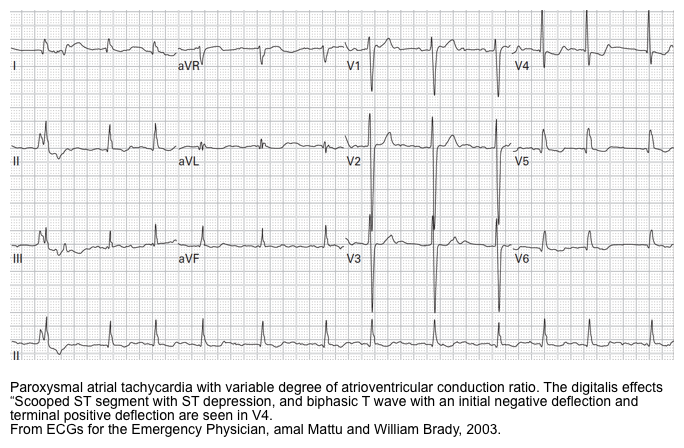

- Signs of digoxin toxicity (see here).

- Rhythm diagnosis (e.g., sinus bradycardia vs. heart block). This will be discussed below.

◾️Labs

- Fingerstick glucose.

- Hypoglycemia alters the physiology of the myocardium. It has proarrhythmic effects and prolongs the QTc, which can lead to Torsades de pointes.

- Hypoglycemia can also induce hypokalemia, which further causes arrhythmias and can lead to sudden death *.

- Chemistries including Ca & Mg.

- Consider hyperkalemia early in an evaluation, and if possible, obtain bedside potassium levels.

- Troponin, if MI is suggested by history/ECG.

- Serum drug level (e.g., digoxin level, for patients taking digoxin).

- Consider checking TSH.

- Hypothyroidism can cause sinus node dysfunction, AV blocks, and even Torsade de pointes *.

- Infectious titers (rapid plasma reagin for syphilis or Lyme).

- Complete blood count with cultures if an infection is suspected.

- Coagulation panel (in an appropriate clinical context).

◾️Imaging

- Head CT scan to rule out ↑ICP, if intracranial pathology is suspected (e.g, hemorrhage, mass, etc.).

- Chest X-ray if there is concern for decompensated heart failure, pacemaker lead fracture, or migration.

- CT of the abdomen if there is concern for intra-abdominal hemorrhage.

Overview of Management Principles

| ⭐️The patient with bradycardia should be approached first based on “hemodynamic stability”. |

- Management of bradycardia is based on various factors, including “hemodynamic stability, severity of symptoms, and the risk of progression to third-degree AV block or asystole” *.

- The approach to treating a patient with bradycardia begins with identifying whether the patient is stable or unstable (Figure below).

🟥Unstable bradycardia

- Definition. “Unstable bradycardia” is defined when both of the following conditions are met:

- “Unstable” is defined by any of the following: hypotension, decreased level of consciousness, ischemic chest pain or anginal equivalent, or acute heart failure.

- If any of the above are presumed to be due to bradycardia, then the patient is assumed to have an “unstable bradyarrhythmia”.

- Management. Unstable patients require resuscitation.

- Assess for potential life-threatening causes of bradycardia (drug toxicity, hyperkalemia, etc.) in parallel with resuscitative measures *.

◾️Hemodynamically stable patients

- Severity of signs and symptoms

- Asymptomatic bradycardia.

- Symptomatic bradycardia defined as “when both of the following conditions are met” *:

- Syncope or Presyncope, Transient Dizziness or Lightheadedness, and Exertional Dyspnea.

- “Documented Bradycardia” is directly responsible for the above presentations.

- Management. Generally, efforts should be made to identify and treat the underlying causes of bradycardia.

- Therapeutic strategies depend on the “Severity of symptoms”, “Reversibility of underlying Causes“, and “Risk of Progression to Asystole“.

- ⚠️Conditions with a “High Risk of Progression to Asystole“ include *:

- Recent asystole.

- Mobitz type II AV block.

- Complete AV block with wide QRS.

- Ventricular pause greater than 3 seconds *

- In such conditions, strongly consider admitting the patient to the ICU for closer monitoring (even if the patient is asymptomatic), further evaluation, and possible permanent pacemaker implantation (if indicated) *.

- ⚠️Conditions with a “High Risk of Progression to Asystole“ include *:

- Therapeutic strategies depend on the “Severity of symptoms”, “Reversibility of underlying Causes“, and “Risk of Progression to Asystole“.

- ⚠️Caution

- Be Cautious for Severely Bradycardic and Normotensive Patients. These patients may be in an occult shock state (discussed above).

- 💡Look for other clinical indicators of poor perfusion, such as “Altered mental status, Ischemic chest pain, and Pulmonary congestion”.

- ⛔️Avoid Treating Hypertension in Patients with “Severe Bradycardia and Hypertension”.

- ⚠️Vasodilation can lead to hemodynamic collapse.

- Be Cautious for Severely Bradycardic and Normotensive Patients. These patients may be in an occult shock state (discussed above).

Treatment lines for bradycardia (overview)

- Medications (see Appendix 1). For more on this, see here.

- Electrical treatment

- Emergent cardiac pacing: Two forms of cardiac pacing are used in the ED:

- Transcutaneous pacing

- Temporary transvenous pacing

- Note that while patients with reversible causes of bradycardia may require temporary pacemaker support, a permanent pacemaker is rarely needed *.

- Permanent pacemaker (PPM): The definitive treatment of symptomatic bradycardia is permanent pacemaker implantation. See indications here.

- Emergent cardiac pacing: Two forms of cardiac pacing are used in the ED:

ECG Evaluation: Diagnosis The Rhythm

Conduction system anatomy

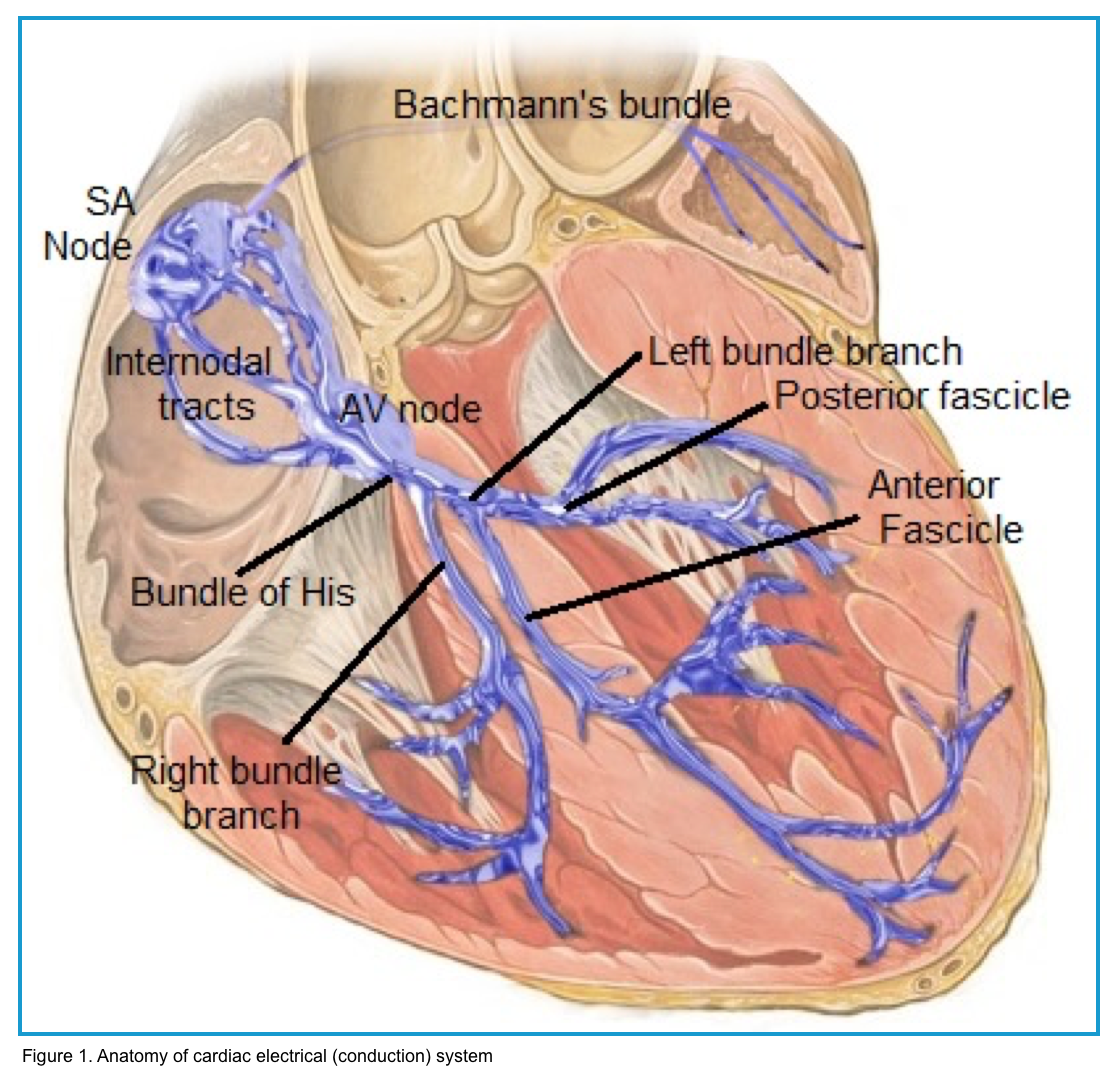

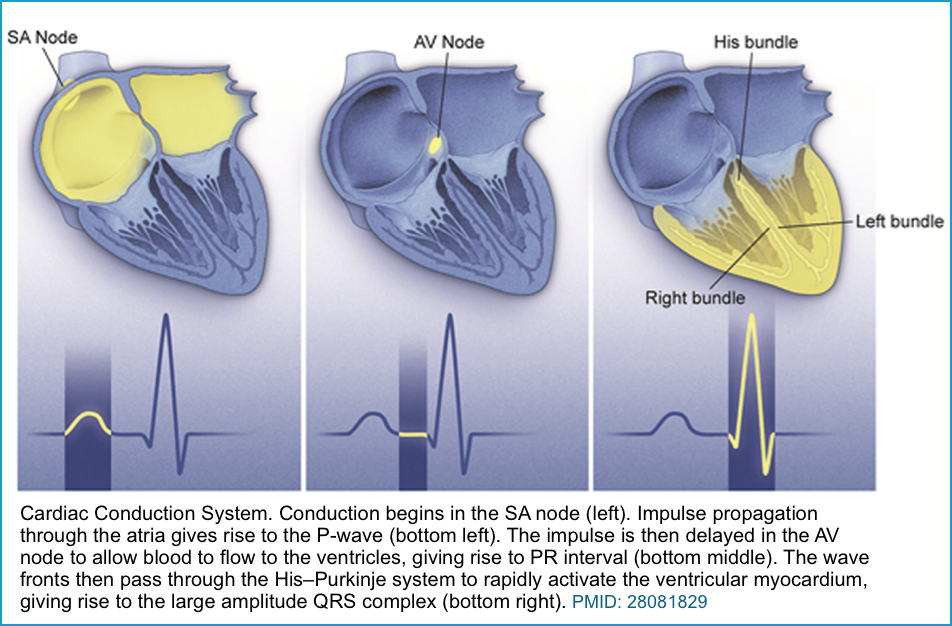

The cardiac electrical (conduction) system is a group of specialized cells present in the walls of the myocardium.

◾️Sinoatrial node (SAN) *

- Normally, it initiates depolarization waves leading to atrial systole.

- Rate: 50-90 bpm at rest; however, autonomic system balance influences the firing rate.

- SN refers to a collection of specialized (pacemaker cells) in the high right atrium. It is composed of two cell types:

- P cell: The central core of the pacemaker cell that produces impulses. Failure of P cells results in actual sinus pause/arrest.

- T cell: The outer layer of SAN that transmits the sinus impulse into the atrium. Failure of T cells results in sinoatrial exit block (SAEB).

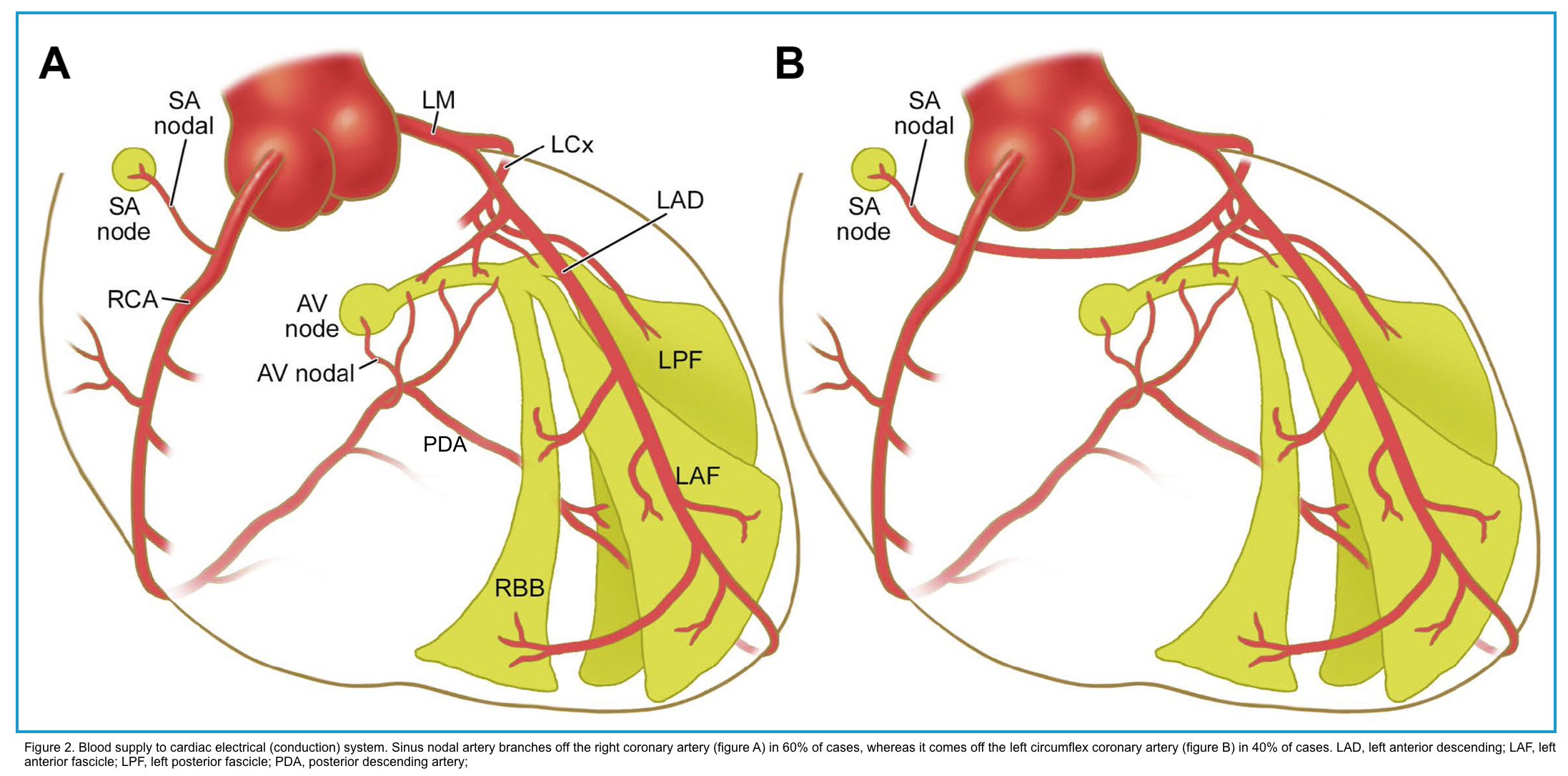

- Blood supply: Sinus node artery that has variable anatomic origins.

- In 60%, it branches off the right coronary artery.

- In 40%, it comes off the left circumflex coronary artery *.

◾️Atrioventricular node (AVN) *

- A group of specialized cells at the AV septum (near the opening of the coronary sinus) that normally serves as the lone electrical connection between atria and ventricles.

- The AVN delays the impulses by ~ 120 msec to ensure the “atria have enough time to eject blood into the ventricles before the ventricular systole”.

- This delay accounts for the majority of the PR interval measured on the ECG.

- The autonomic nervous system balance can modulate the AV nodal delay (PR interval).

- Blood supply: AV nodal artery.

- In 90%, it originates from the posterior descending artery (PDA).

- In 10%, it comes off the left circumflex artery *.

◾️Bundle of His

- This transmits electrical impulses from the AVN to the ventricles.

- It descends the membranous part of the interventricular septum before dividing into two main bundles (i.e., right and left bundle branches).

- Blood supply: Branches of the left anterior descending (LAD) and posterior descending (PDA) coronary arteries.

- This dual supply makes the conduction system at this site more invulnerable to ischemic damage unless the ischemia is extensive *.

◾️Bundle branches: These are extensions of the His bundle, conducting electrical impulses to the ventricles.

- Right bundle branch (RBB)

- Transmits the impulse to the Purkinje fibers of the right ventricle.

- Blood supply: Septal perforators of the left anterior descending (LAD) artery.

- Left bundle branch (LBB)

- Transmit the impulse to the Purkinje fibers of the left ventricle. The LBB typically divides into two fascicles: anterior and posterior.

- Left anterior fascicle

- Blood supply: Septal perforators of LAD.

- Left posterior fascicle

- Blood supply: A dual blood supply via both PDA and LAD.

- Left anterior fascicle

- Transmit the impulse to the Purkinje fibers of the left ventricle. The LBB typically divides into two fascicles: anterior and posterior.

◾️Purkinje fibers (sub-endocardial plexus of conduction cells)

- These cells are located in the subendocardial surface of the ventricular walls.

- Transmit cardiac action potentials from the atrioventricular bundle to the myocardium of the ventricles.

Mechanism of bradycardia

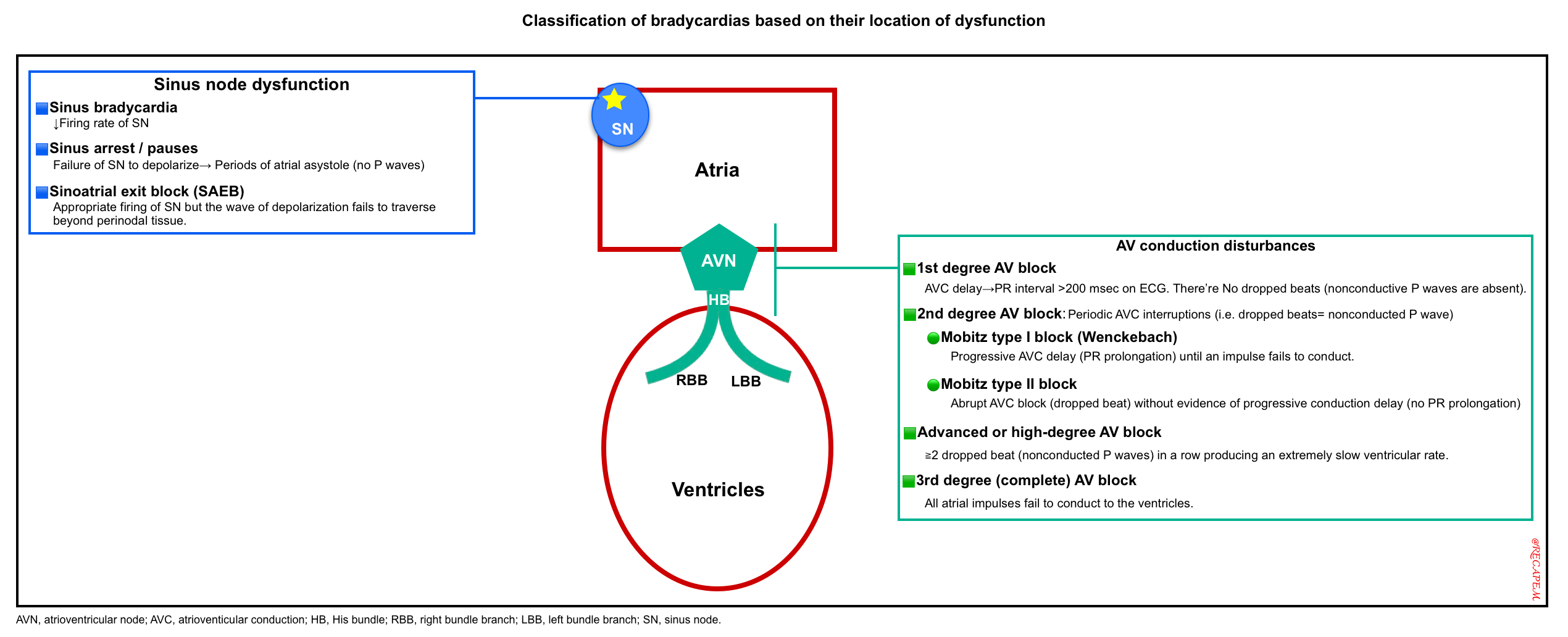

◾️With a basic understanding of the cardiac conduction system, it is possible to classify bradycardias based on their location of dysfunction (figure below). This classification determines prognosis and guides further therapeutic decisions.

Subtypes of bradycardic rhythm

Electrocardiography (ECG) establishes the diagnosis. Subtypes of bradyarrhythmia on ECG include:

- Sinus node dysfunction (SND)

- Sinus bradycardia

- Sinus pause/arrest

- Sinoatrial exit block (SAEB)

- Tachycardia-bradycardia syndrome

- AV conduction disturbances

- First-degree AV block

- Second-degree AV block

- Mobitz type I (Wenckebach)

- Mobitz type II

- Advanced or high-degree AV block

- Third-degree (complete) AV block with a junctional or ventricular escape rhythm

- Escape rhythms

- Junctional escape rhythm

- Ventricular escape rhythm

- Atrial fibrillation or flutter with a slow ventricular rate

- Group beating

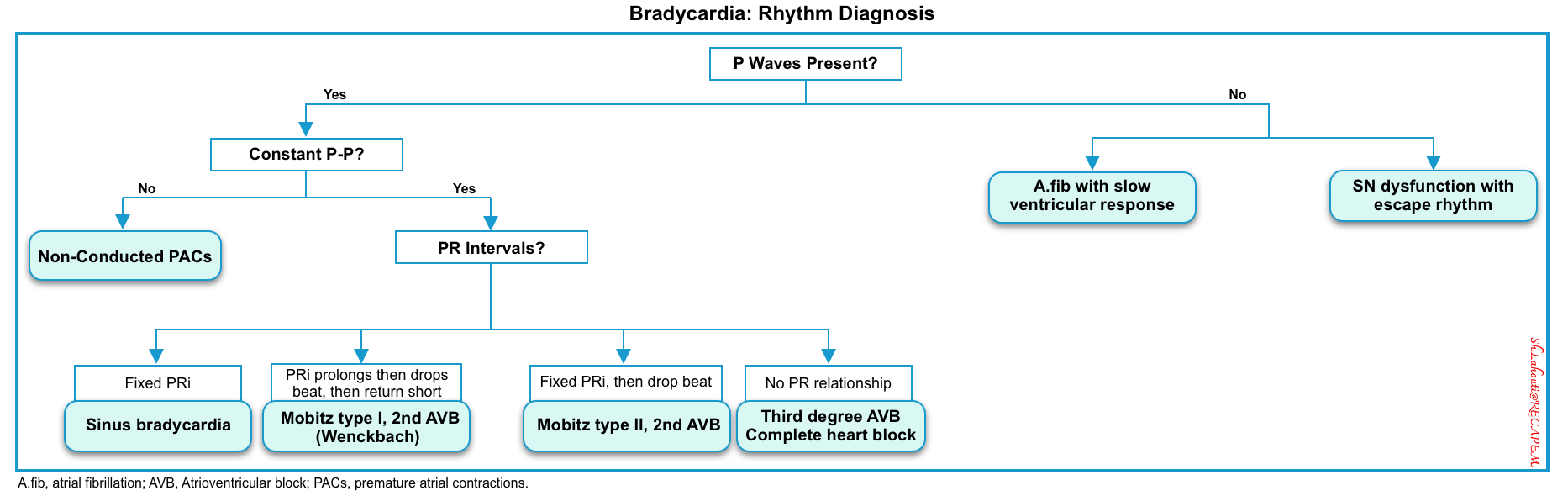

Analysis of ECG in bradycardia

- PP interval reveals sinus node dysfunction.

- PR interval reflects AV node dysfunction.

- The bundle branch block may reflect conduction system dysfunction.

Sinus node dysfunction (SND)

- Sinus node dysfunction, sometimes used interchangeably with “sick sinus syndrome“, refers to a spectrum of dysrhythmias including sinus bradycardia, sinus pause/arrest, sinoatrial exit block, and tachycardia–bradycardia syndrome *.

◾️Clinical significance

- Symptoms attributable to SND can range from mild fatigue to frank syncope.

- Other clinical symptoms include dyspnea on exertion, lightheadedness, and chronic fatigue.

- The severity of clinical manifestations generally correlates with the heart rate or the pause duration.

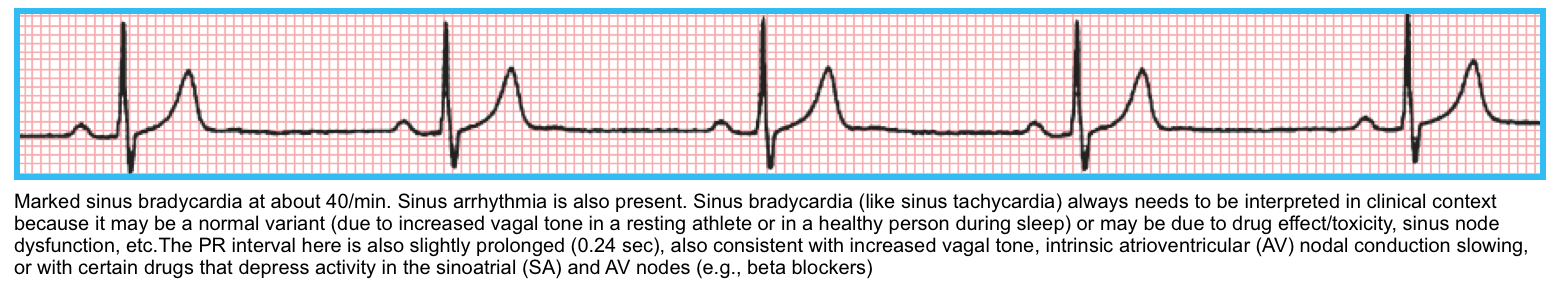

Sinus bradycardia

◾️Definition

- Sinus bradycardia is characterized by a regular rhythm with normal P-wave morphology (upright in leads I and II) and a rate of <60 bpm.

- It can be further classified as mild (rates between 50-59 bpm), moderate (40–49 bpm), or severe (<39 bpm). Jane Chen 2014.

◾️Mechanism (pathophysiology)

- Decreased firing rate of the sinus node pacemaker cells (either physiologic, as in athletes with a high cardiac vagal tone at rest, or pathologic).

- SA exit block.

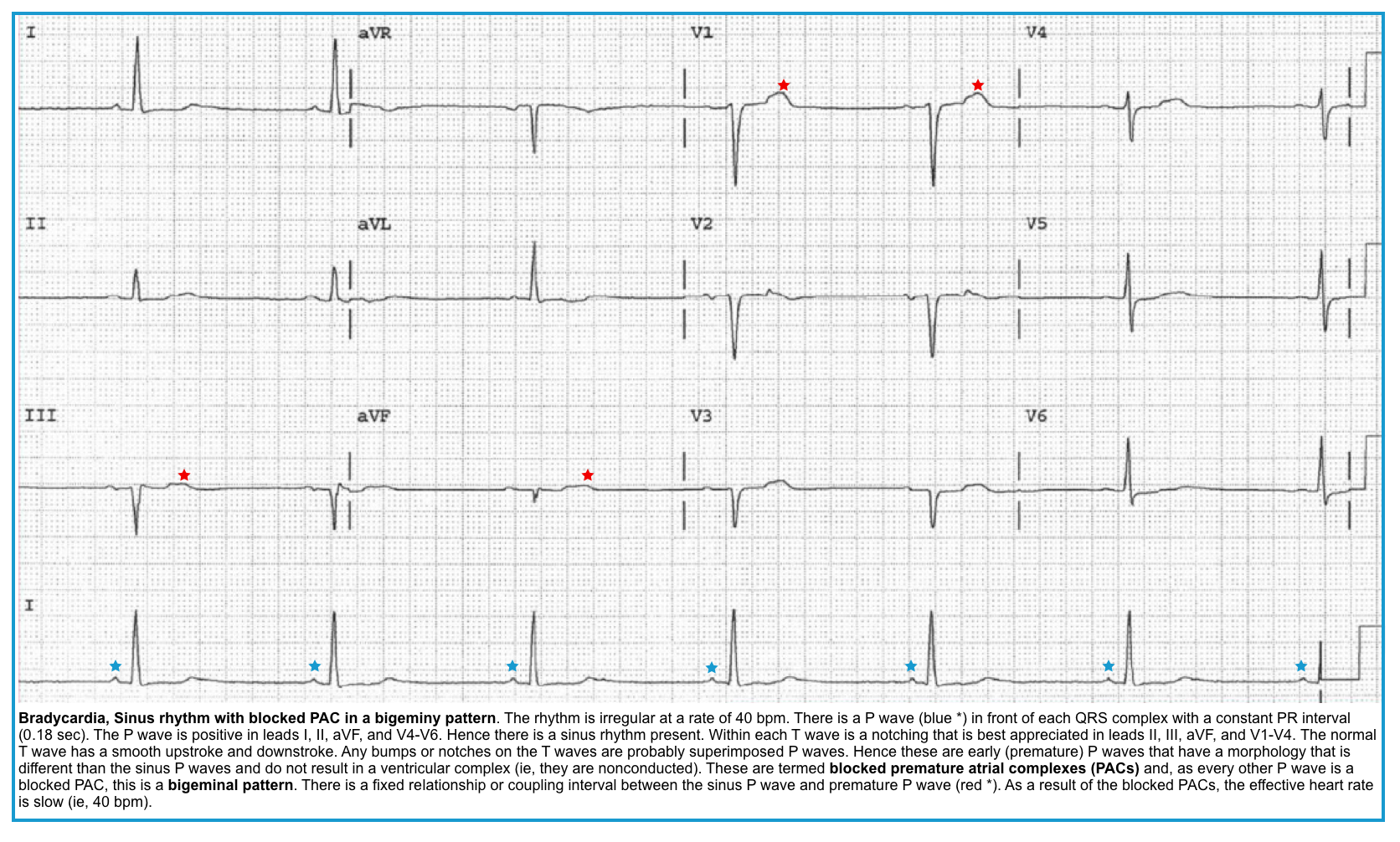

◾️ECG differential diagnosis

- SAEB. Consider a 2:1 sinoatrial exit block if the heart rate is < 40 bpm (more on this, below)

- Frequently blocked PACs (more on this, below).

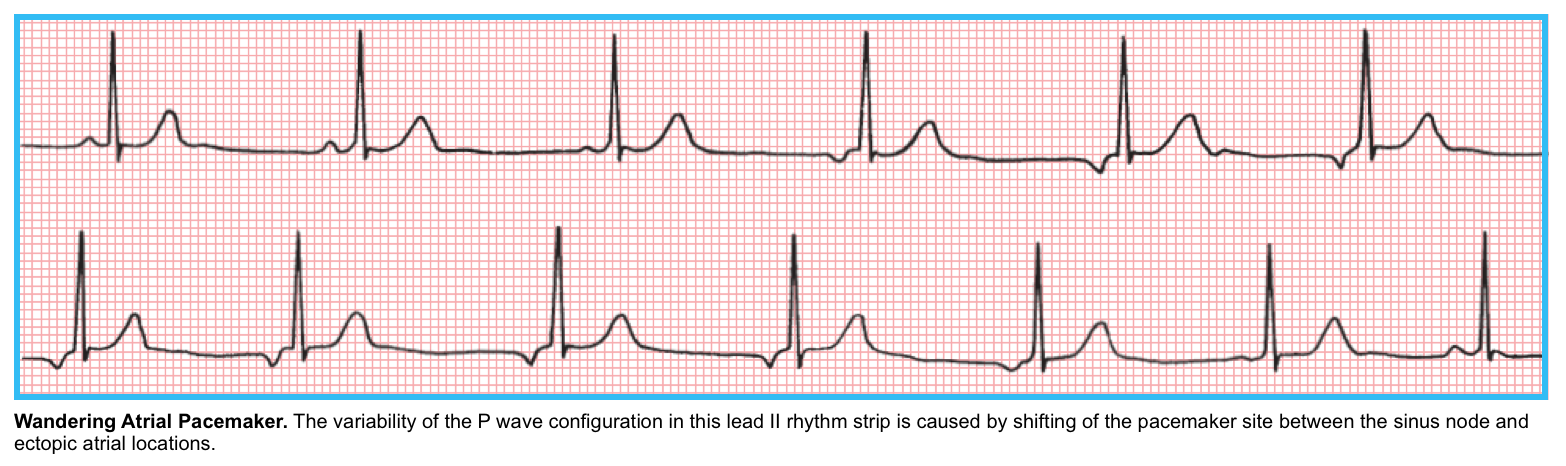

- Wandering Atrial Pacemaker (WAP)

- WAP is characterized by multiple P waves of varying configurations with a relatively normal or slow heart rate. The P-wave variations reflect the shifting of the intrinsic pacemaker between the sinus node (and likely regions within the SA node itself) and different atrial sites.

- Causes of WAP

- Physiological variant: It often appears in normal persons (particularly during sleep or states of high vagal tone).

- Drug toxicities.

- Sick sinus syndrome.

- Different types of organic heart disease.

◾️Clinical significance

- Many healthy people have a resting pulse rate of less than 60 bpm, and trained athletes may have a resting or sleeping pulse rate as low as 35 bpm. Sinus bradycardia is also routinely observed during sleep in healthy subjects.

- Sinus bradycardia is usually not clinically significant unless the heart rate is < 50 bpm.

- Moderate sinus bradycardia is usually asymptomatic.

- If the heart rate is very slow (especially < 30–40 bpm in the elderly), lightheadedness and even syncope may occur.

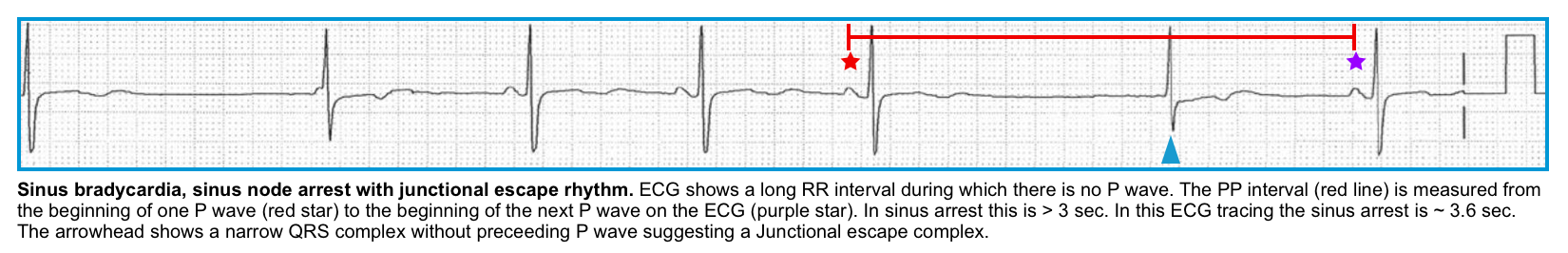

Sinus pause/arrest

◾️Pathophysiology

- It happens due to the actual failure of the SAN to fire for one or more beats.

◾️ECG findings

- PP interval (measured from the beginning of one P wave to the beginning of the next on the ECG ) > 3 seconds *. That equals 15 “big boxes” on a standard ECG.

- Note that the pause is not a multiple of the baseline P-P interval (that would be a sinoatrial exit block, discussed below) *.

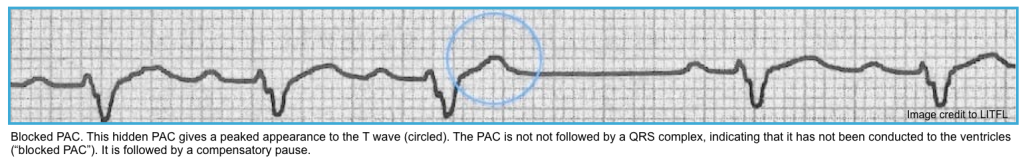

◾️ECG differential diagnosis:

- Suppression by PACs: Look for a PAC preceding the dropped beat; it may be buried in the T-wave (Figure below).

- ⭐️Blocked PACs are the most common cause of a pause.

- The slow pulse (QRS) rate is due to the post-atrial ectopic pauses.

- Sinoatrial exit block: Here, the long cycle is a multiple of the baseline PP intervals (will be discussed below).

- Marked sinus arrhythmia.

- Overdrive suppression after ectopic tachycardia.

◾️Clinical significance of sinus pause/arrest

- Pauses < 3 seconds are commonly seen in healthy people and are rarely symptomatic.

- Pauses > 3 seconds and not occurring during sleep are often pathologic and may cause symptoms.

- This can be a criterion for pacemaker placement in the context of sick sinus syndrome *.

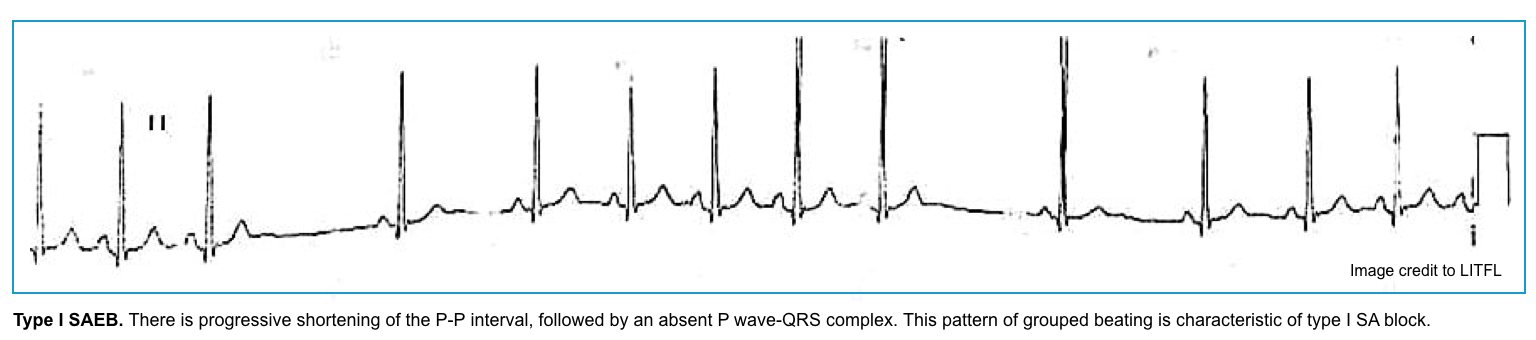

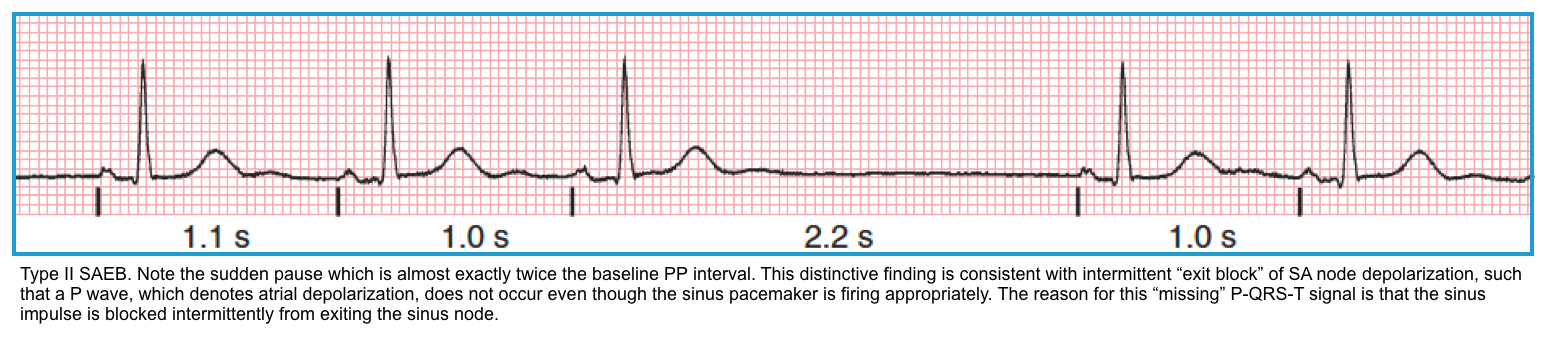

Sinoatrial exit block

- It happens when the sinus node impulses are blocked from exiting the node and stimulating the atria.

- Key finding: The P-P interval is a multiple of the prior P-P interval (2x, 3x, etc.).

- Pattern of conduction failure:

- Mobitz I: Progressive shortening of PP interval (resulting in progressive shortening of RR intervals) until a P wave is dropped.

- Here, the atrial impulse is generated, but transmission is delayed. This delay becomes progressively longer, which results in pushing successive P-waves closer. Therefore, P-P gets progressively shorter until a P wave is dropped.

- The PP pause is less than twice the normal PP interval.

- Mobitz II: Sudden drop of a P wave, without progressive PP shortening.

- The pause is near multiple of the normal PP interval.

- Mobitz I: Progressive shortening of PP interval (resulting in progressive shortening of RR intervals) until a P wave is dropped.

- It may be seen in 1% of normal subjects.

- Evaluation and treatment of symptomatic sinus node dysfunction are similar to the treatment of bradycardia in general.

- For persistent sinus node dysfunction, consider the placement of a permanent pacemaker *.

Tachycardia-bradycardia syndrome

Tachycardia-bradycardia syndrome describes a subset of symptomatic SND who have periods of fast heart rates (supraventricular tachycardia, usually AF) interspersed with episodes of slow heart rates (sinus bradycardia or sinus pause/arrest) and slow sinus rates or pauses *.

- During periods of supraventricular tachycardia, atrial fibrillation is commonly the underlying rhythm, although other types of supraventricular tachycardia can be observed.

- On cessation of tachyarrhythmia, there may be a period of delayed sinus recovery, e.g., sinus pause or exit block.

- One of the most disabling symptoms of tachy-brady syndrome is recurrent syncope or presyncope secondary to transient asystolic pause that follows termination of paroxysmal episodes of supraventricular tachycardia (typically AF).

Heart block

Key points

Atrioventricular (AV) block is a bradyarrhythmia caused by a delay or interruption in the electrical conduction between the atria and the ventricles. This occurs due to either anatomic or functional impairment. Depending on the severity of the block, patients may be asymptomatic or may present with syncope, chest pain, dyspnea, and bradycardia.

◾️What is the degree of AV block?

- The severity of conduction impairment determines the degree of AV block.

- Based on the increasing severity of conduction impairment, three degrees of AV block are described.

- Note that the degree of AV block (i.e., 2nd-degree or 3rd-degree) signifies the severity of the AV conduction delay

- The degree of AV block does NOT determine the site of AV block.

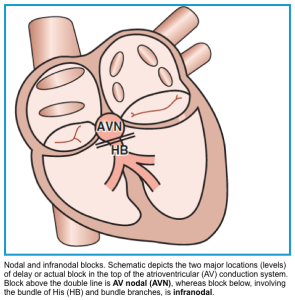

◾️Site of the conduction block (where is the most likely level of the block?)

- Interruption of electrical conduction can occur at any level, from the AV node (nodal block) down to the bundle of His and its branches (hence the term infranodal block). See the figure below.

⭐️Determining the site of the block is important as it has clinical and prognostic implications.

- ⚠️As a general rule, infranodal block carries a worse prognosis (it requires pacemaker implantation) for the following reasons: *

- Clues to nodal versus infranodal site of AV block (below table). Goldberger 2018

| Clues | Nodal block | Infranodal block |

| Onset and progression | A gradual onset with a slower progression. | An abrupt onset and A rapid progression to complete heart block. |

| PR interval prolongation | PRI prolongation is seen before the block. 1st-degree AVB with significant PRI prolongation (>240ms), and Mobitz type I AVB. | Sudden block w/o PRI prolongation, or (with minimal PRI prolongation) Mobitz type II AVB. |

| Escape rhythm rate | FASTER (40–60 bpm) and More RELIABLE (junctional escape rhythm) | SLOWER (< 40 bpm) and More UNPREDICTABLE (ventricular escape rhythm). |

| Escape rhythm QRS duration | Narrow QRS < 120 ms. | Wide QRS > 120 ms (ventricular escape rhythm) |

| Signs of conduction disease | Often absent | May be present (e.g. BBB, HFB, bifascicular block) |

| Hemodynamics | Stable | Often unstable |

| Responsiveness to atropine | Greater response | Poor response |

| Responsiveness to catecholamines | Greater response | Sometimes improves * |

- QRS duration

-

- Nodal AV block

- The QRS complexes are narrow, i.e., ≤120 msec (unless the patient has an underlying bundle branch block).

- Infranodal block

- The QRS is usually wide ( >120 msec).

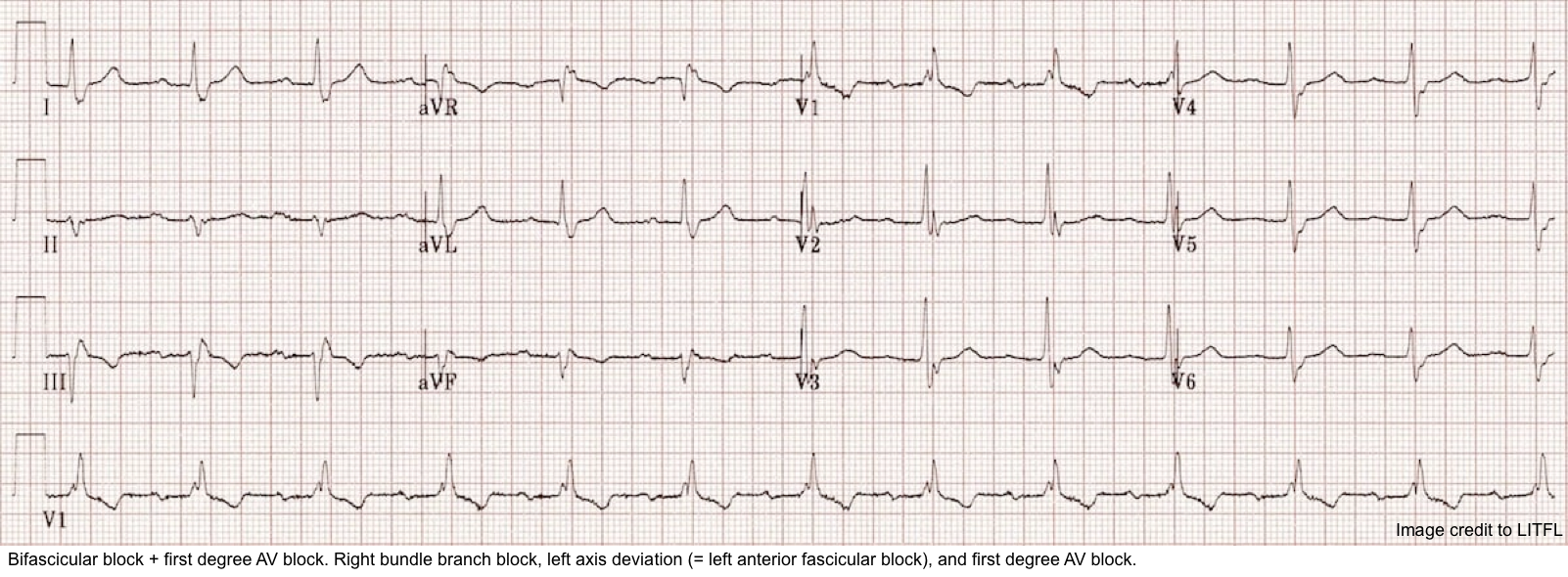

- Other signs of conduction disease are usually present (bundle branch blocks, hemiblocks, or nonspecific QRS widening, shown in the following ECG). See Dr. Smith’s Blog for more on this.

- Nodal AV block

- PR interval prolongation

- First-degree AVB with significant PRI prolongation (i.e., PRI >240 ms) or Mobitz type I AV block usually suggests nodal AV block.

- Normal or minimally prolonged PRI or Mobitz Type II AV block often suggests an infranodal block.

- See more explanation in the following boxes (expand to read more). Goldberger 2018

The nodal block usually occurs gradually. Conduction through the AVN is relatively sluggish (relying on slowly depolarizing calcium channels), accounting for most of the PR interval duration.

As the block progresses, a significant additional PR interval prolongation usually occurs before conduction fails, leading to a second- or third-degree block. (Analogy: Consider the stretching of an elastic band before it snaps.)

Infranodal block, in contrast, usually happens abruptly. Conduction through the infranodal structures is relatively fast (relying on rapidly conducting sodium channels), accounting for a very small portion of the PR interval.

Therefore, there is minimal or no visible PR prolongation in the infranodal block, and the block (second- or third-degree) appears abruptly. (Analogy: Consider the sudden snap of a metal chain under stress.)

Because the AVN is located at the very top of the specialized conduction system, there are multiple potential escape or “backup” pacemakers located below the level of block (i.e., in the lower parts of the AVN as well as the bundle of His and its branches).

Pure nodal and His bundle escape rhythms have narrow QRS complexes and a moderately low rate (e.g., 40–60 bpm). However, the QRS complexes may be wide if there is an associated bundle branch block.

Generally, with the block at the nodal level, the associated escape rhythm is sufficient to maintain an adequate cardiac output (at least at rest).

Idioventricular escape mechanisms usually produce regular, wide QRS complexes with a very slow rate (i.e., <40 bpm). With an infranodal block, this will be the escape rhythm.

The SAN and AVN share a common physiology, and their function tends to change in parallel. Both are sensitive to autonomic (sympathetic and parasympathetic) stimulation, and drugs affecting the autonomic nervous system (e.g., β-blockers, atropine, digoxin). For example, vagal stimulation can simultaneously produce both sinus bradycardia and AV block.

Stimulation with sympathomimetic (e.g., epinephrine) and anticholinergic drugs (e.g., atropine) increases the sinus rate and facilitates AV conduction.

The infranodal conduction system does not share the same physiologic responsiveness to autonomic modulation or pharmacologic intervention, and is not similar to nodal tissues. Infranodal block often worsens with an increase in heart rate. Drugs causing tachycardia, such as atropine and sympathomimetics, may unexpectedly worsen conduction in infranodal block.

However, beta-agonists are useful in speeding up the rate of an idioventricular escape pacemaker in cases of complete infranodal block in emergency settings.

- AV block happening in the setting of myocardial infarction

- If inferior MI, the site of the block is AVN. Goldberger 2018

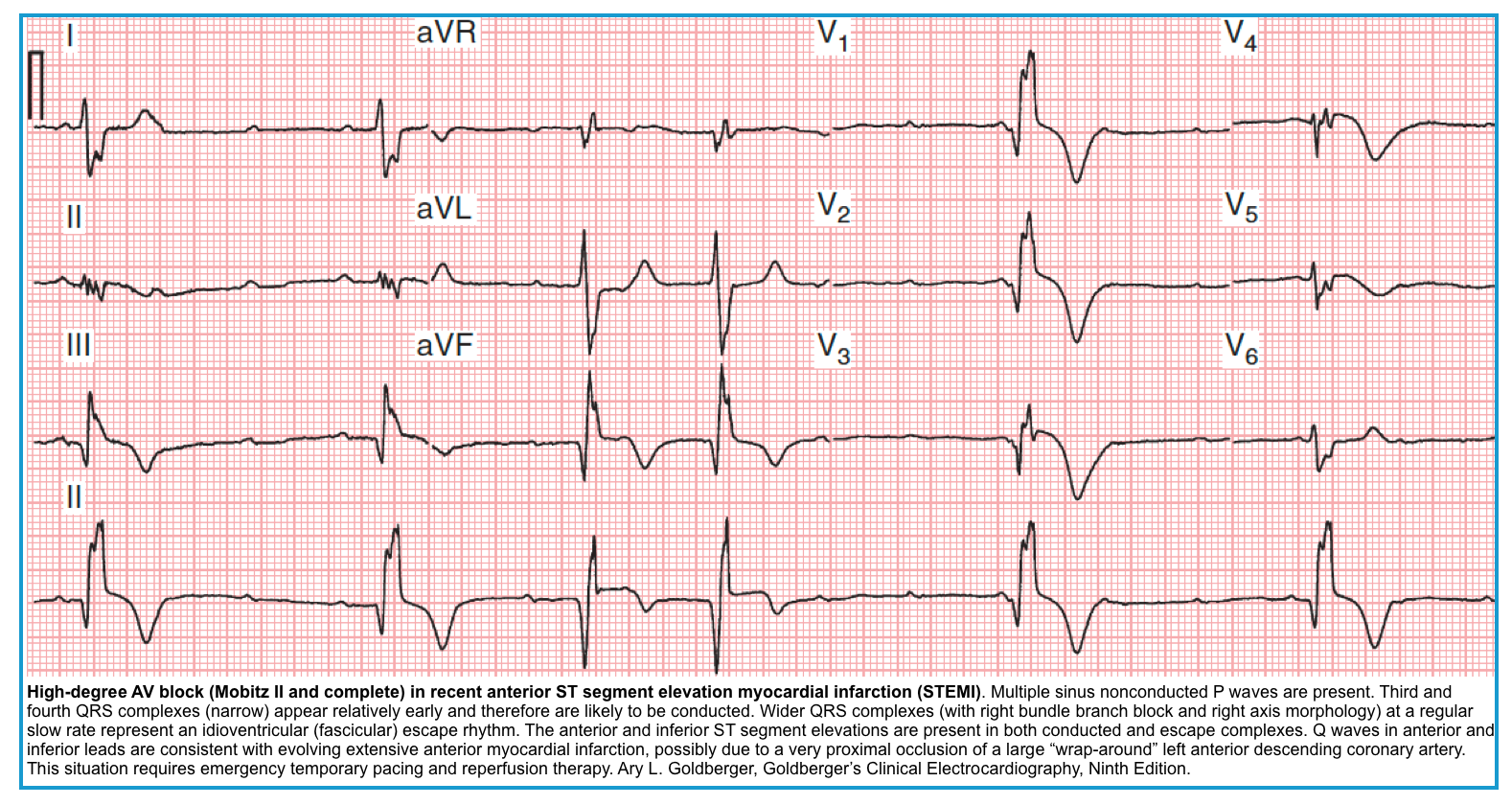

- If it is anterior MI, the site of the block is more likely infranodal.

| Inferior MI | Anterior MI |

| Sinus bradycardia, sinus pauses, nodal AVB | Infra-nodal AVB |

| SA node and AV node ischemia, increased vagal tone | Ischemia of His-Purkinje system |

| 1st-degree, 2nd-degree type I, and 3rd-degree AVB | 2nd-degree type II and 3rd-degree AV block |

| Transient | Permanent |

| Good response to medications | Poor response to medications |

Clinical Points

| ✅Narrow QRS bradycardias usually have a better prognosis and do not require permanent pacemakers. ✅These cases are usually vagally induced or the result of a reversible cause (eg, beta blocker overdose). |

| ⚠️Second-degree AV block type II, complete AV block, ventricular pause >3 sec, and a wide complex bradycardia without a reversible underlying cause, will usually require aggressive resuscitation and eventual permanent pacemaker insertion. |

First-degree AV block

◾️Background

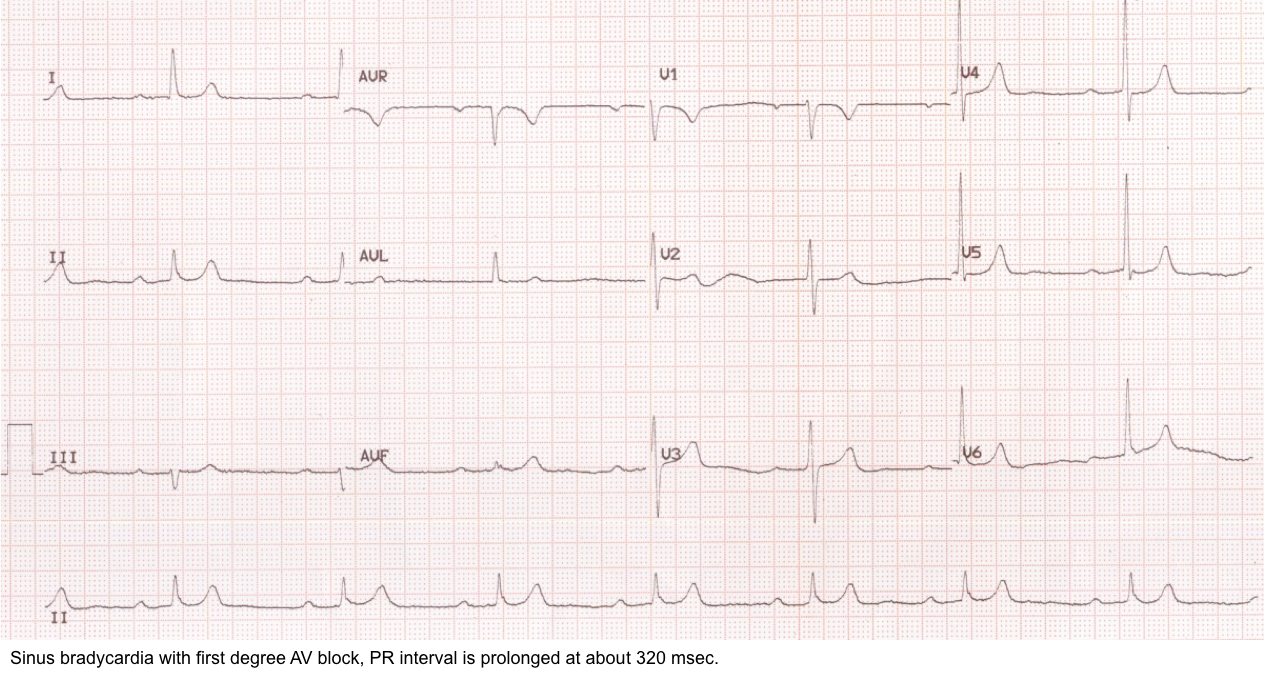

- The first-degree atrioventricular block is a misnomer since a true block is not present (as each P wave is conducted, but with a prolonged PR interval >200 ms). It is more accurately referred to as “first-degree atrioventricular delay” *.

- All P waves are conducted but with a delay (prolonged PRI) in a 1st-degree AV block.

◾️ECG

- PR interval >200 ms (5 boxes).

- Constant PR intervals.

- Absence of non-conducted P waves (NCPW) *.

◾️Site of the block (explained above)

- In most cases, the site of the block is within the AV node.

- Rarely, the block could be infranodal. Clues for infranodal block include:

- PR interval prolongation is < 240 ms (abnormal His-Purkinje conduction seldom prolongs conduction >200 ms).

- Wide QRS (>120 msec).

- Presence of other signs of conduction disease (bundle branch blocks, hemiblocks, trifascicular block, or nonspecific QRS widening).

◾️Clinical significance

- Isolated 1st-degree AV block is often benign and does not cause hemodynamic instability. No specific treatment is required.

- “Marked 1st-degree AV block” is present if PR interval > 300 msec (P waves may be buried in the preceding T wave) *.

- ⚠️This may cause loss of atrial kick, which may be associated with symptoms such as fatigue and even syncope (“pseudo-pacemaker syndrome”), especially in patients with left ventricular dysfunction *.

- The site of the block in most cases with a first-degree AV block is within the AV node.

- ⚠️Block below the AV node (e.g., with wide QRS) is more likely to progress to complete heart block.

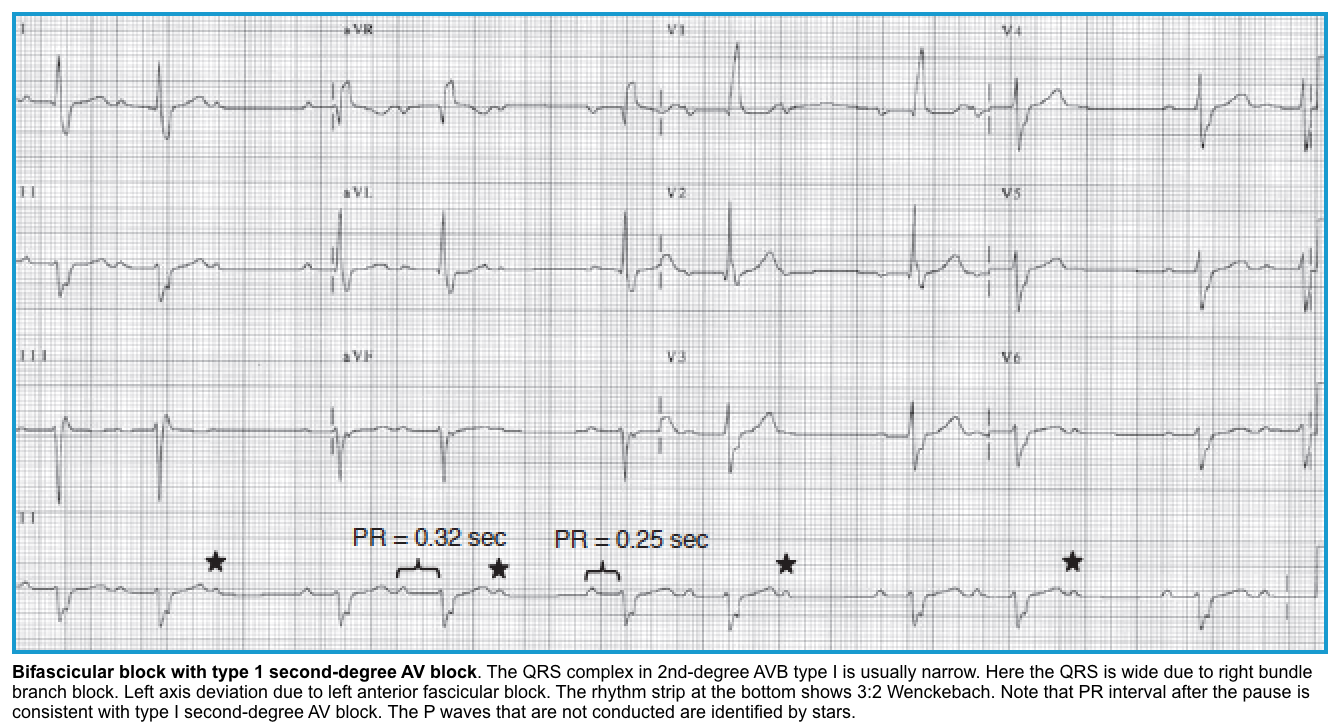

Second-degree AV block

🔳General considerations

- Second-degree AV block can be either Mobitz type I (Wenckebach conduction) or type II.

- A non-conducted P-wave (NCPW) is typically present in second-degree AV block.

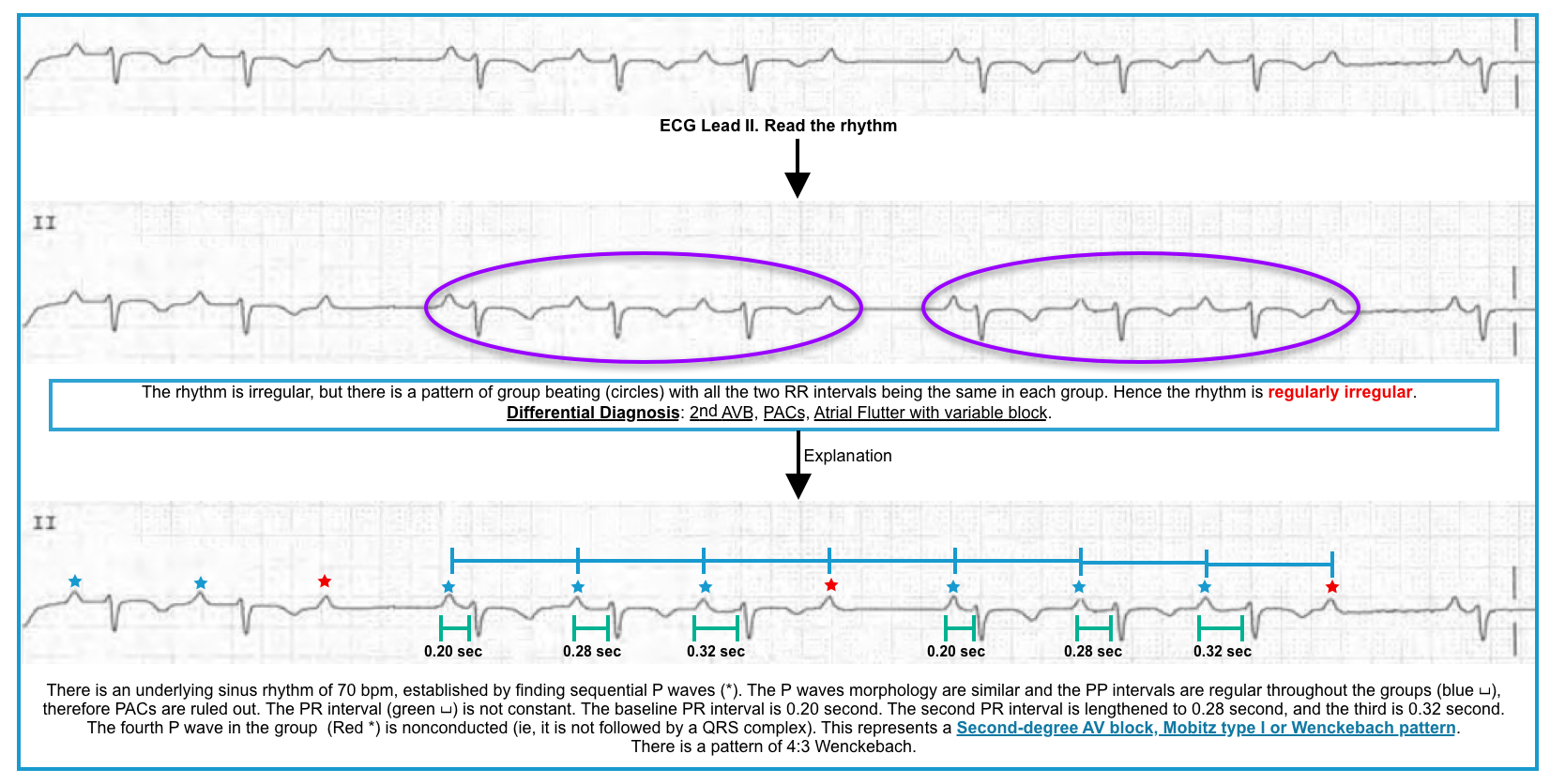

- The ECG will show group beating due to “dropped” QRS complexes *.

- The conduction ratio in the second-degree AV block is mentioned as the ratio between the number of P waves (in a Wenckebach cycle) and the number of QRS complexes. For example, if 3 P waves are conducted and the 4th one is blocked, it is called a 4:3 Wenckebach block.

🔳Clinical significance

- Second-degree AV block is benign when it occurs in the AV node. However, pacing is often required when the block is infranodal.

- An EP study is indicated if the level of block is not clear.

- AV block due to acute ischemia can occur in the Cardiovascular Intensive Care Units, and knowledge of the patient’s coronary anatomy is critical in determining management.

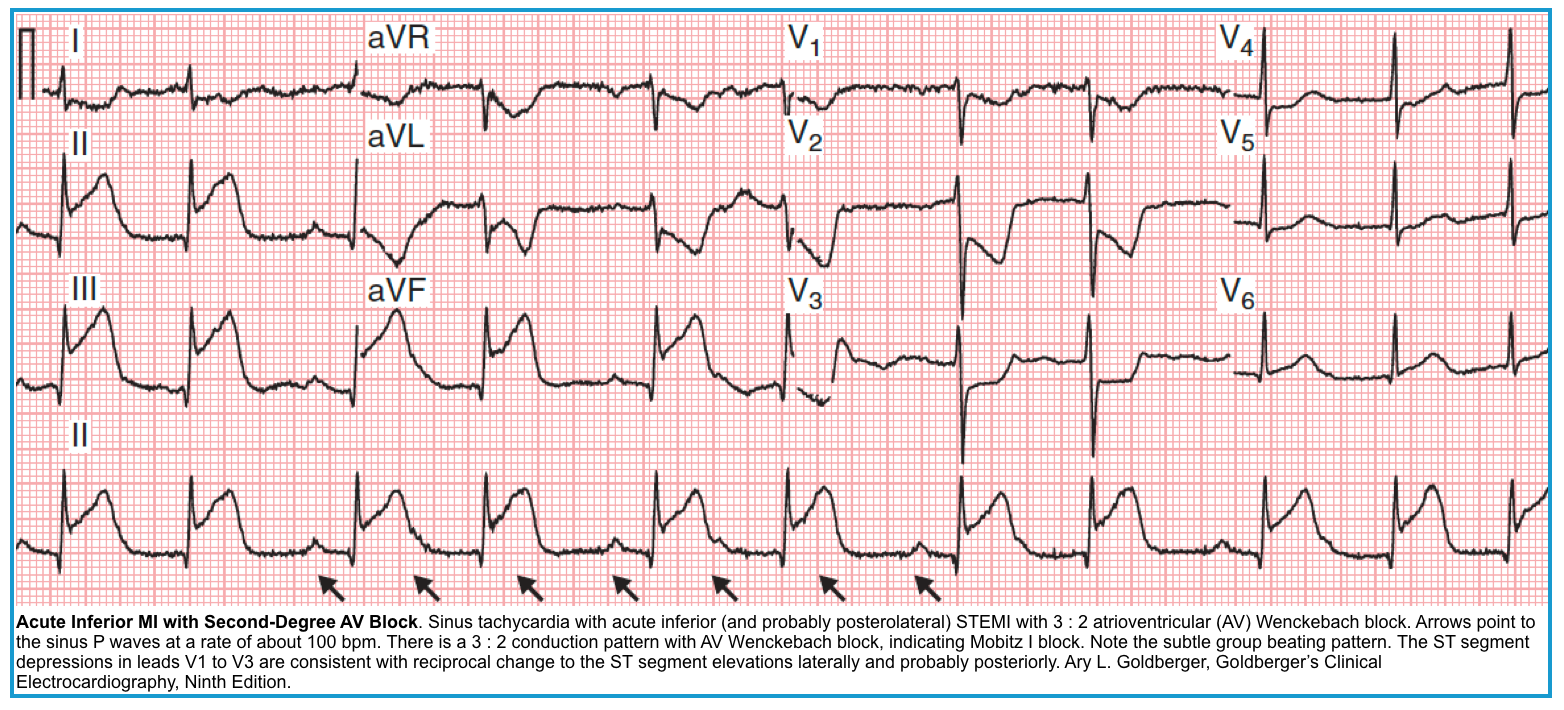

- Ischemia of the right coronary artery, which supplies the AVN, can cause second or third-degree AV block, which can be transient *.

- The AV nodal block is usually responsive to atropine.

- AV block due to left anterior descending artery (LAD) ischemia is usually infra-nodal and will either fail to respond or worsen with atropine *.

- AV block caused by LAD ischemia rarely resolves with revascularization, and pacing is often indicated *.

- Ischemia of the right coronary artery, which supplies the AVN, can cause second or third-degree AV block, which can be transient *.

Mobitz Type I block (Wenckebach)

◾️Mechanism

- Mobitz I is usually due to a functional/ reversible suppression of AV conduction (e.g., due to drugs, reversible ischemia).

- Malfunctioning AV nodal cells tend to fatigue until they fail to conduct an impulse progressively.

- The second-degree AV block associated with inferior wall infarction is Mobitz type I.

◾️ECG

- Progressive prolongation of the PR interval culminating in a non-conducted P wave (NCPW) *.

◾️Clinical significance

- Mobitz type I block is usually more benign, causing minimal hemodynamic disturbance *.

- It is often asymptomatic and seen in active, healthy patients with no history of heart disease.

- However, if occurring frequently or during exercise, it can cause symptoms of exertional intolerance or dizziness.

- Progression to complete AV block is less common *.

- Even if it progresses to a complete heart block, the escape rhythm has a narrow QRS and a good rate.

- Asymptomatic patients do not require treatment.

- Symptomatic patients usually respond well to atropine *.

- Permanent pacing is rarely required.

Mobitz Type II block

◾️ECG

- The PR interval is fixed. There may be no prolongation of the baseline PR interval.

- There is an abrupt drop of a QRS (a non-conducted P wave is present) *.

- There may be no pattern to the conduction blockade, or there may be a fixed relationship between the P waves and QRS complexes, e.g., 2:1 block, 3:1 block.

◾️Mechanism

- Mobitz type II block usually originates below the His bundle.

- In around 75% of cases, the conduction block is located distal to the Bundle of His, producing broad QRS complexes.

- In the remaining 25% of cases, the conduction block is located within the His Bundle itself, producing narrow QRS complexes.

- Mobitz Type II is more likely to be due to structural damage to the conducting system (e.g., infarction, fibrosis, necrosis).

◾️ECG differential diagnosis

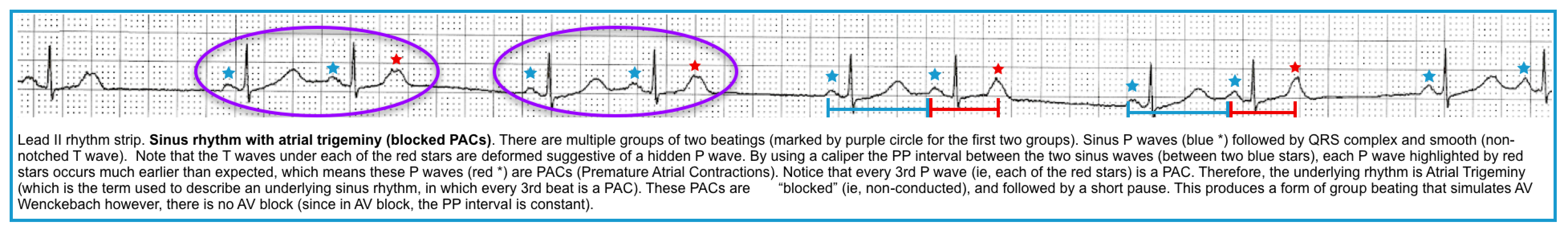

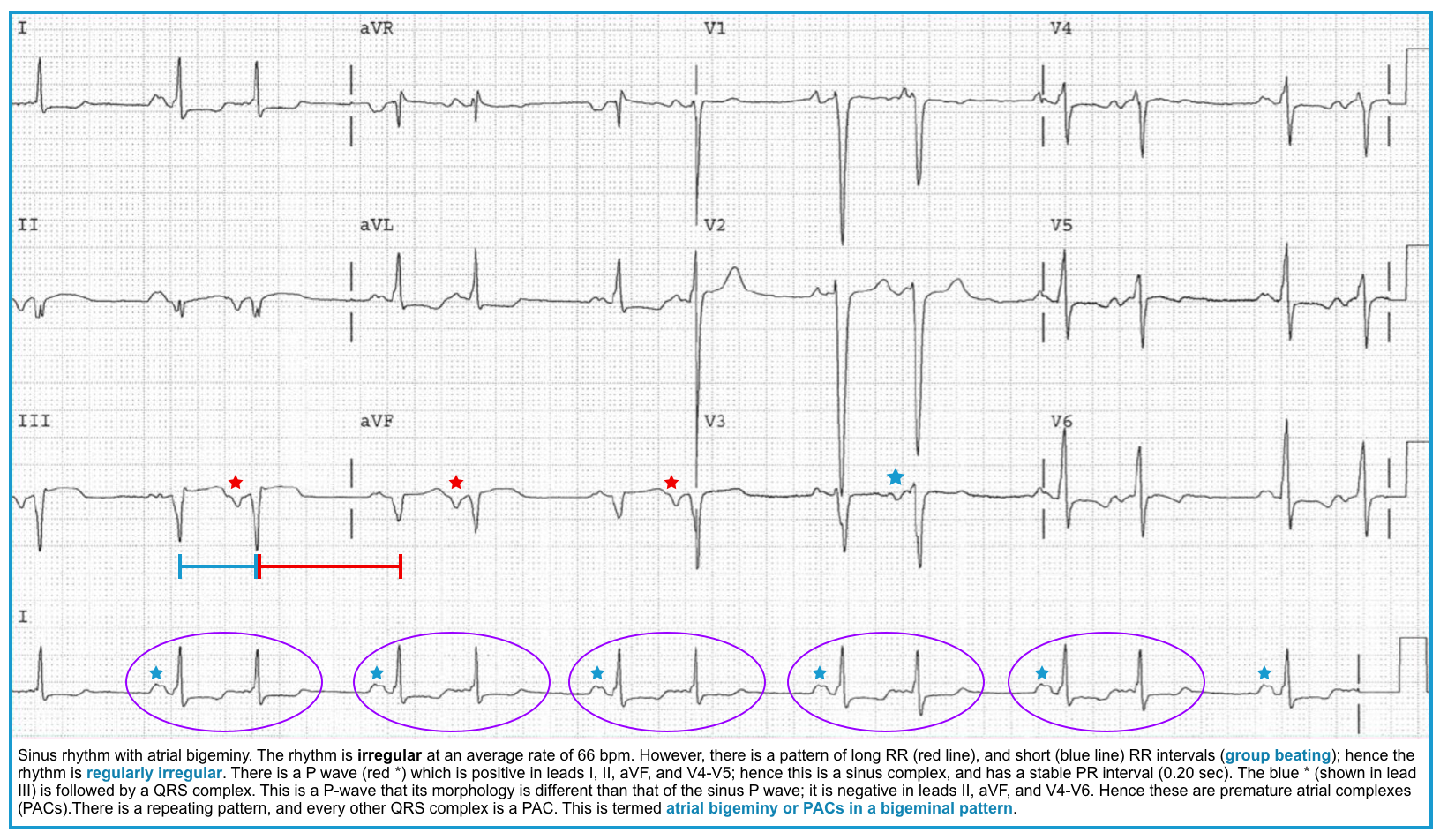

- Nonconducted (blocked) PACs.

- AV block with 2:1 ratio: This is the classic situation where differentiating Mobitz I vs. Mobitz II may be ambiguous *.

- When the atrioventricular conduction (AVC) ratio is 2:1, it is typically called untypable AVB (since differentiating type I from type II requires the presence of at least two conducted P-waves before the nonconducted P-wave to see if the PR interval is prolonged or not) *.

- The helpful distinguishing clues are summarized in the following table.

| Suggesting features | Mobitz type I | Mobitz type II |

| QRS duration | Narrow | Wide |

| History and associated condition | Inferior MI | History of syncope Anterior MI |

| Response to atropine | Improves | Worsen |

-

-

- Features suggesting Mobitz type I

- QRS has a narrow complex (although Mobitz II can occur with a narrow QRS complex if the block occurs within the His bundle).

- Association with inferior MI.

- Improves with exercise, atropin, and beta-agonists.

- Features suggesting Mobitz type II

- QRS has a widened complex (e.g. bifascicular block).

- Intermittent conduction blocks may sometimes occur. Even if these occur with regular timing within clumps (e.g., right bundle branch Wenckebach), any infranodal block supports a Mobitz II diagnosis.

- History of syncope.

- Association with anterior MI.

- Mobitz II worsens with exercise, atropin, and beta-agonists (speeding up the P-wave speed will exaggerate the severity of the block).

- QRS has a widened complex (e.g. bifascicular block).

- Features suggesting Mobitz type I

-

◾️Clinical significance

- Mobitz II carries a more ominous prognosis *. If it progresses to a complete heart block, the escape rhythm would be wide QRS, lower rate, and unstable.

- Mobitz II is much more likely than Mobitz I to be associated with hemodynamic compromise, severe bradycardia, and progression to 3rd-degree heart block.

- The onset of hemodynamic instability may be sudden and unexpected, causing syncope (Stokes-Adams attacks) or sudden cardiac death.

- The risk of asystole is around 35% per year.

- Mobitz II mandates “Immediate admission for cardiac monitoring, Backup temporary pacing, and ultimately insertion of a Permanent Pacemaker” *.

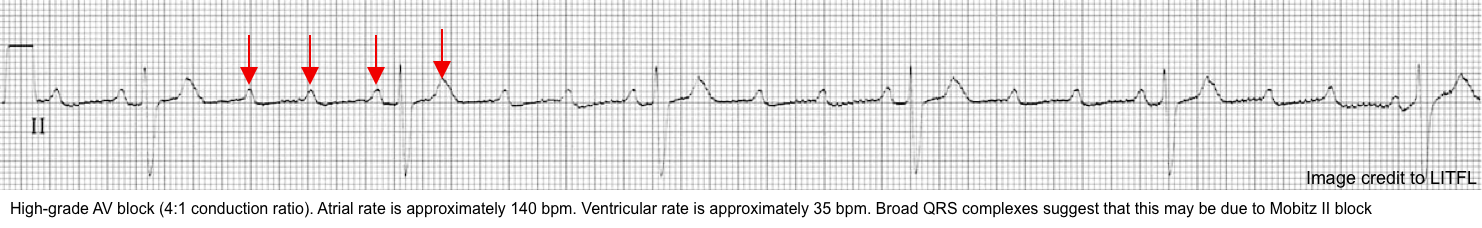

Advanced or high-grade AV block

◾️High-grade, high-degree, or advanced AV block refers to situations where ≥2 consecutive P waves at a normal rate are not conducted (without complete loss of atrioventricular conduction) *.

◾️ECG

- ≧2 non-conducted P waves in a row producing an extremely slow ventricular rate *.

- There is often a fixed ratio of P-waves to QRS complexes (e.g., 4:1 conduction ratio).

◾️Clinical significance

- High-grade AV block can occur at any level of the conduction system (either nodal or infranodal block). Goldberger 2018

- A common mistake is to call this pattern Mobitz II block or complete heart block.

- “Urgent admission for cardiac monitoring, Backup temporary pacing, and usually insertion of a Permanent Pacemaker” is warranted *.

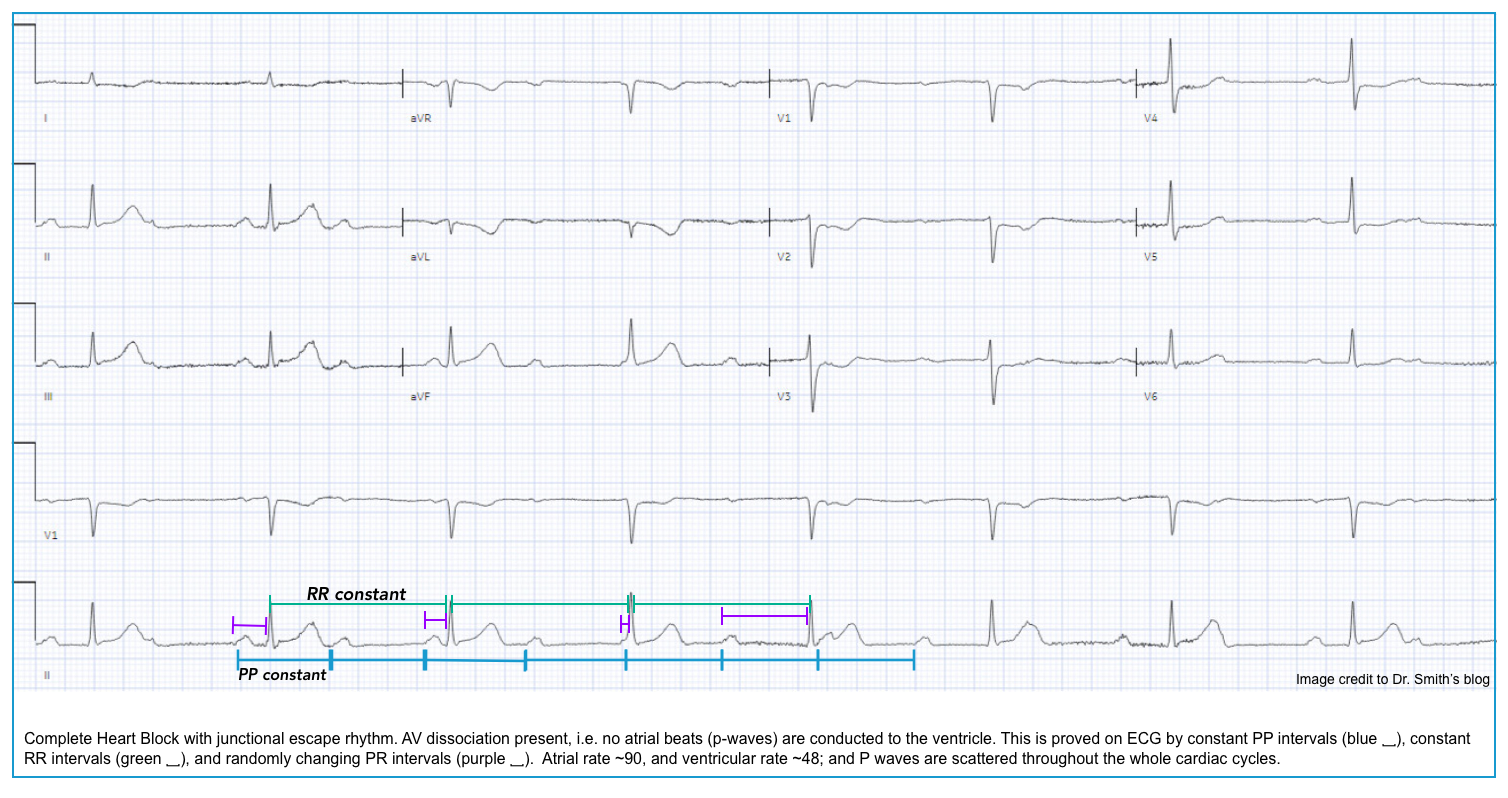

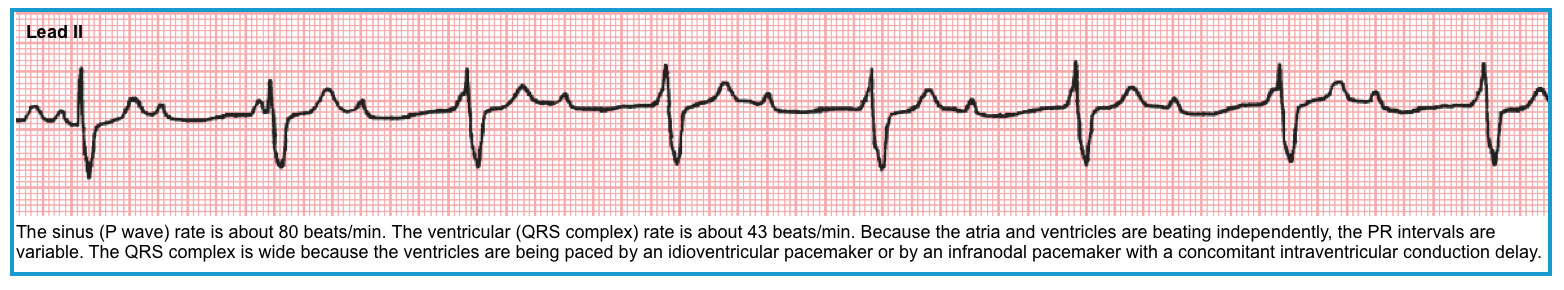

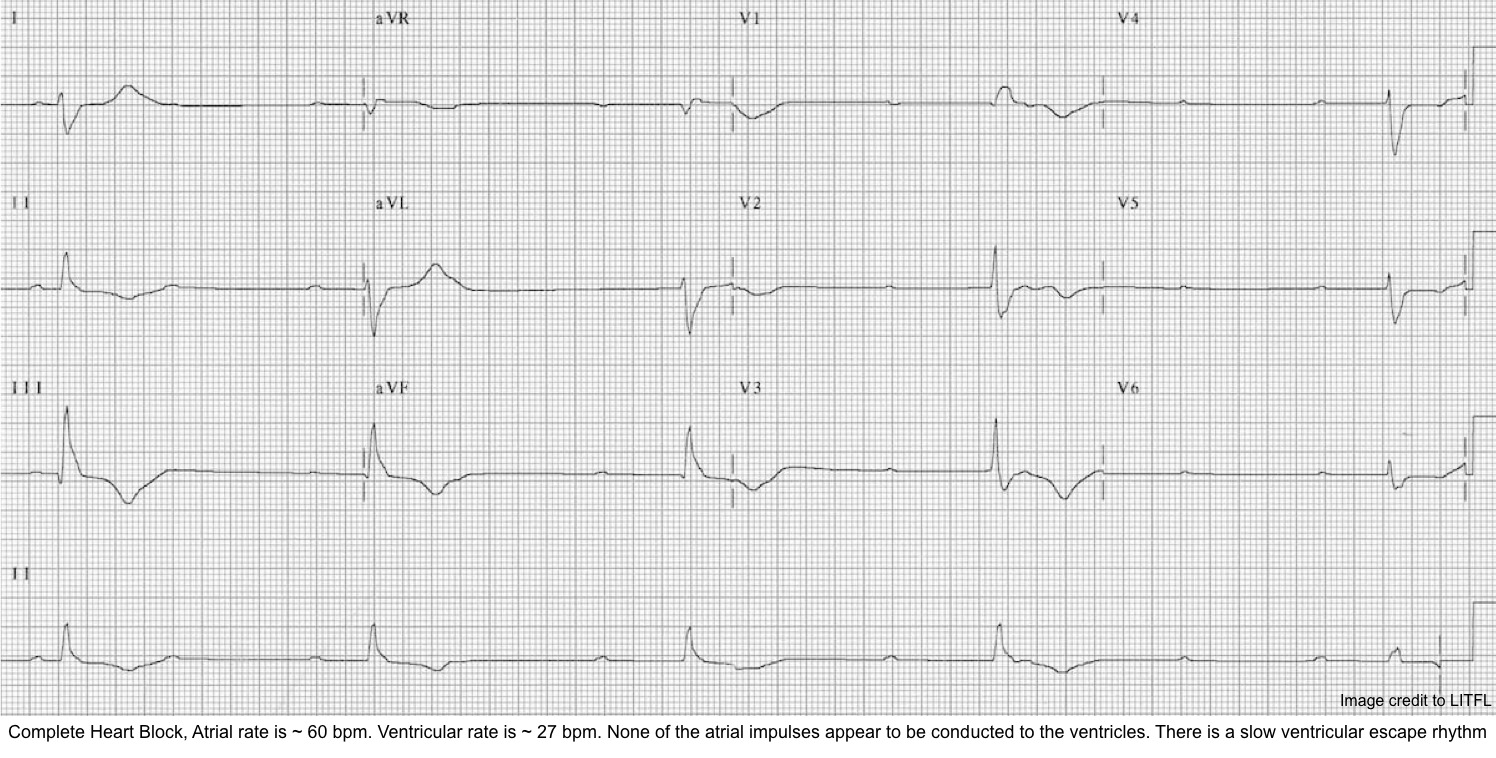

Third-degree AV block

◾️Background

- Complete heart block (CHB) is the most life-threatening type of bradyarrhythmia.

- Generally, a complete heart block is the endpoint of a second-degree AV block.

- With second-degree AV block (either Mobitz I or II), some atrial beats are conducted to the ventricles.

- With third-degree AV block (complete heart block), no stimuli are transmitted from the atria to the ventricles (i.e., complete absence of AV conduction) *.

- The atria and ventricles are paced independently with a separate pacemaker at a different rate, and there is no“cross-talk” between them (i.e., AV dissociation).

- The atria may continue to be paced by the SA node (or by an ectopic focus or atrial fibrillatory activity).

- The ventricles are paced by a nodal or infranodal escape pacemaker located below the point of the block.

- This provides a perfusing rhythm. Alternatively, the patient may suffer ventricular standstill, leading to syncope (if self-terminating) or sudden cardiac death (if prolonged).

- The clinical presentation of third-degree AV block is variable depending upon the rate of the underlying escape rhythm and the presence of comorbid conditions.

◾️Causes

- The causes are the same as for bradycardia (discussed above).

- Complete heart block may happen suddenly, as in acute myocardial infarction or as a result of the progression of conducting system disease.

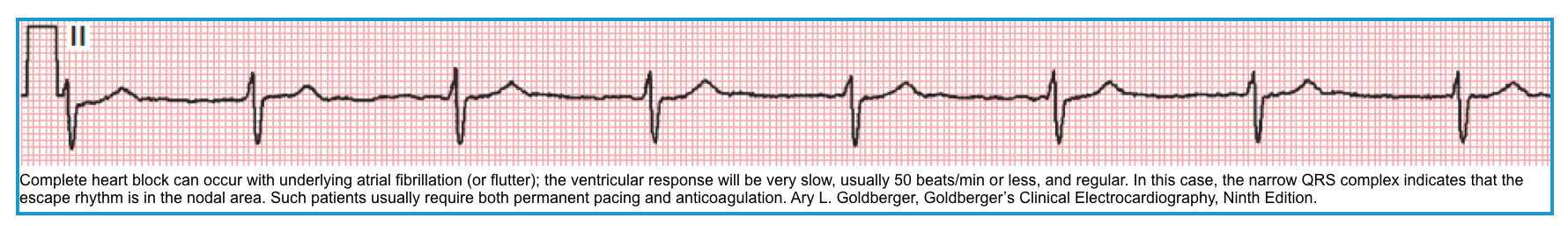

- It may happen in the setting of atrial fibrillation when the ventricular response is slow (<50 bpm) and regular *.

- Diagnostic criteria for a complete heart block include *:

- Complete AV dissociation with independent atrial and ventricular rates (no P waves are conducted to the ventricles).

- Atrial rate > Ventricular rate.

- Note that in the presence of AV dissociation, if the ventricular rate is faster than the atrial rate, then this is not a complete heart block; rather, this is an accelerated rhythm (either junctional or ventricular).

- Ventricular rhythm is maintained by junctional or ventricular escape rhythm with a slow rate (<45 bpm).

- Independent atrial and ventricular activities (AV dissociation) result in:

- Constant PP intervals.

- Constant RR intervals.

- Randomly changing PR intervals: The P waves bear no relation to the QRS complexes; thus, the PR intervals are variable.

Here’s a rare Echo clip of a patient who was in Complete Heart Block. You can actually see the Atria and Ventricles contracting independently. This is what AV Dissociation looks like!#FOAMed pic.twitter.com/YkYXIcjWwA

— Sam Ghali, M.D. (@EM_RESUS) October 16, 2021

◾️Clinical significance

- Development of a complete heart block can be life-threatening, presenting with presyncope or syncope (Stokes–Adams attacks) due to a very slow escape rate or even to prolonged asystole *.

- Severe bradycardia is more likely to occur with infranodal than nodal complete blocks due to the more abrupt onset and the slower rate of the escape rhythms in the infranodal blocks (discussed above).

- If the patient survives this initial episode of complete heart block, the primary complaints are usually severe exertional dyspnea and fatigue due to the inability to augment heart rate and cardiac output with exercise, similar to that of second-degree AV block.

◾️Patients with complete heart block require “Urgent admission for cardiac monitoring, Backup temporary pacing, and usually insertion of a Permanent Pacemaker” *.

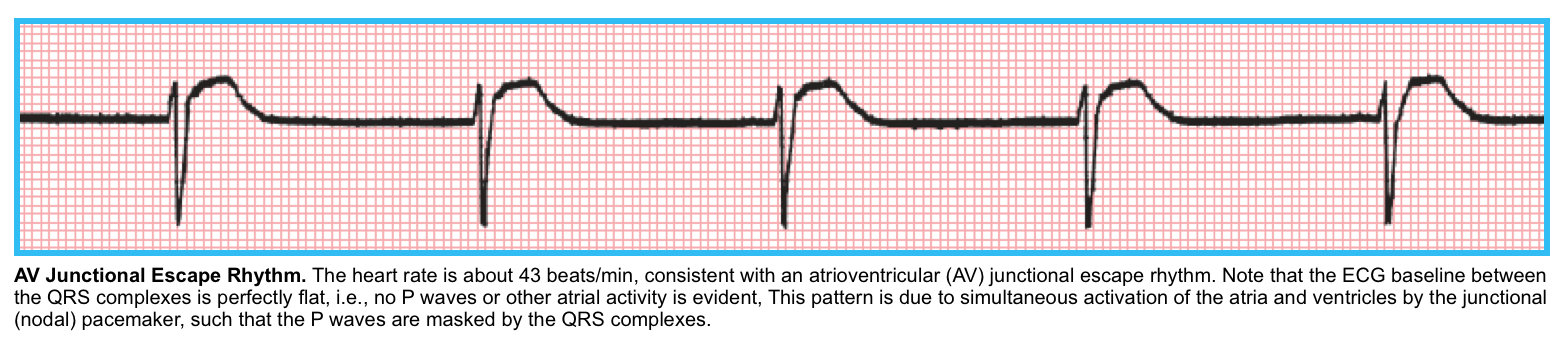

Secondary pacemakers and escape rhythms

- Escape beats (or a sustained escape rhythm if sinus arrest persists) can appear from AV nodal cells (∼35–60 bpm), His–Purkinje cells (∼25–35 bpm), and ventricular myocytes (≤ 25–35 bpm).

- It is important to understand that escape rhythms are not the primary arrhythmias but rather function as “automatic backups” or “compensatory responses”.

- The primary problem is the failure of the higher-order pacemakers or the AV conduction block.

- Therefore, diagnosis and treatment of these primary conditions are the goals.

- Conditions leading to the emergence of a junctional or ventricular escape rhythm include:

- Severe sinus bradycardia, sinus arrest, SAEB, high-grade 2nd AVB, complete heart block.

- Hyperkalemia

- Drugs: Beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, digoxin poisoning.

◾️Escape rhythms

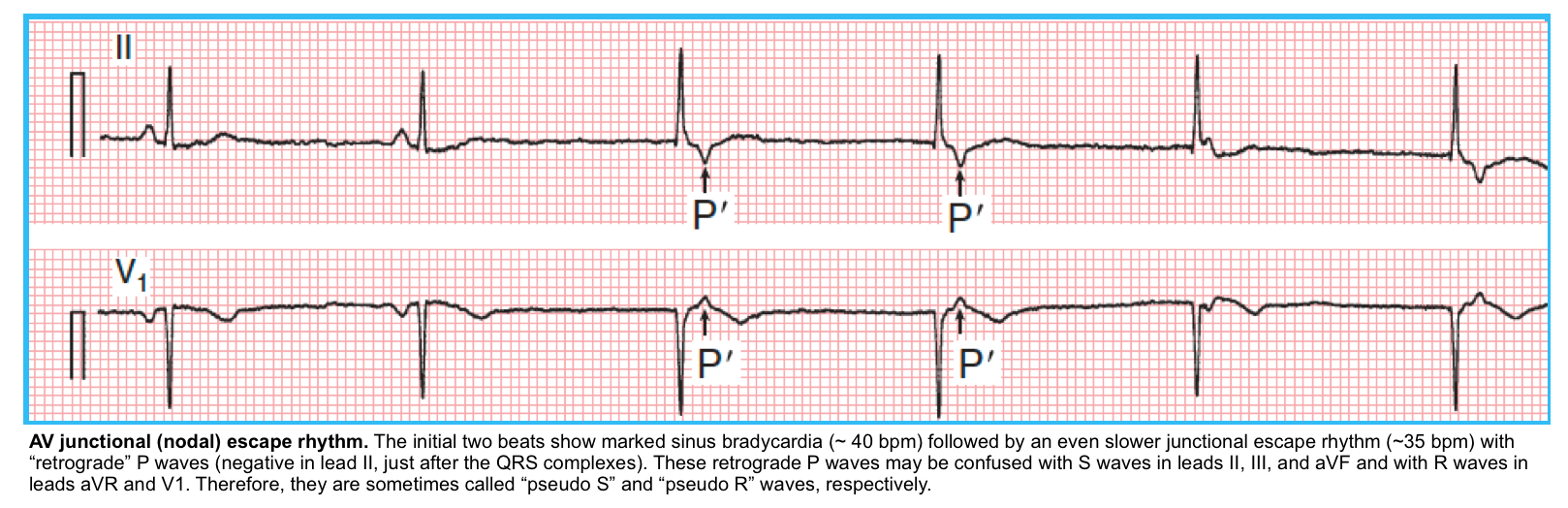

- Junctional escape rhythm (the terms AV junctional, junctional, AV nodal, and nodal are essentially synonymous)

- ECG

- RR interval of escape rhythm:

- Constant (<40 ms variation)

- Rate of <60 bpm (usually ~ 40-55 bpm).

- QRS should be narrow (unless there is an underlying conduction abnormality).

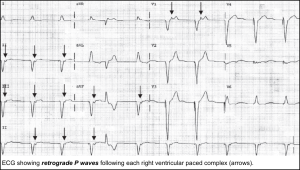

- Retrograde P waves.

- The atria are activated in a retrograde fashion, from bottom to top, producing negative P waves in leads II, III, and AVF, and a positive P wave in lead aVR.

- The inverted P waves are either seen before QRS complexes, buried in QRS complexes, or just after QRS complexes.

- RR interval of escape rhythm:

- Clinical significance

- Junctional rhythms are generally reliable and capable of achieving an adequate rate to support perfusion.

- ECG

- Ventricular escape rhythm (idioventricular escape rhythm)

- When the SA nodal and AV junctional escape pacemakers fail to function, a very slow backup pacemaker in the ventricular conduction (His–Purkinje–myocardial) system may take over. This rhythm is referred to as an idioventricular escape rhythm.

- ECG criteria: All the following must be met:

- The rate is usually < 40-45 bpm (can range from 20-55 bpm).

- The QRS complexes are wide (≥ 120 msec) and may have either LBBB or RBBB morphology without any preceding P waves.

-

- Clinical significance

- ⚠️This rhythm usually indicates a life-threatening situation. These are associated with

- Hypotension

- Hemodynamic instability

- Abrupt transition to pulseless electrical activity or asystole with cardiac arrest.

- ☠️Idioventricular rhythm, usually without P waves, is a common end-stage finding in irreversible cardiac arrest, preceding a “flat-line” pattern.

- If the cause cannot be reversed immediately (e.g., hyperkalemia), a backup pacemaker should be placed (e.g., temporary transvenous pacemaker).

- ⚠️This rhythm usually indicates a life-threatening situation. These are associated with

- Differential diagnosis

- Hyperkalemia may cause a wide-complex bradycardic rhythm with invisible P-waves.

- Junctional escape rhythm with pre-existing conduction disease.

- Differentiating a ventricular escape rhythm versus junctional escape with aberrancy may be based on similar principles that are utilized to differentiate ventricular tachycardia versus supraventricular tachycardia with aberrancy (e.g., capture or fusion beats may help confirm the presence of a ventricular rhythm).

- Accelerated idioventricular rhythm (AIVR)

- If the heart rate is > ~50 bpm, then this may be accelerated idioventricular rhythm (AIVR).

- Clinical significance

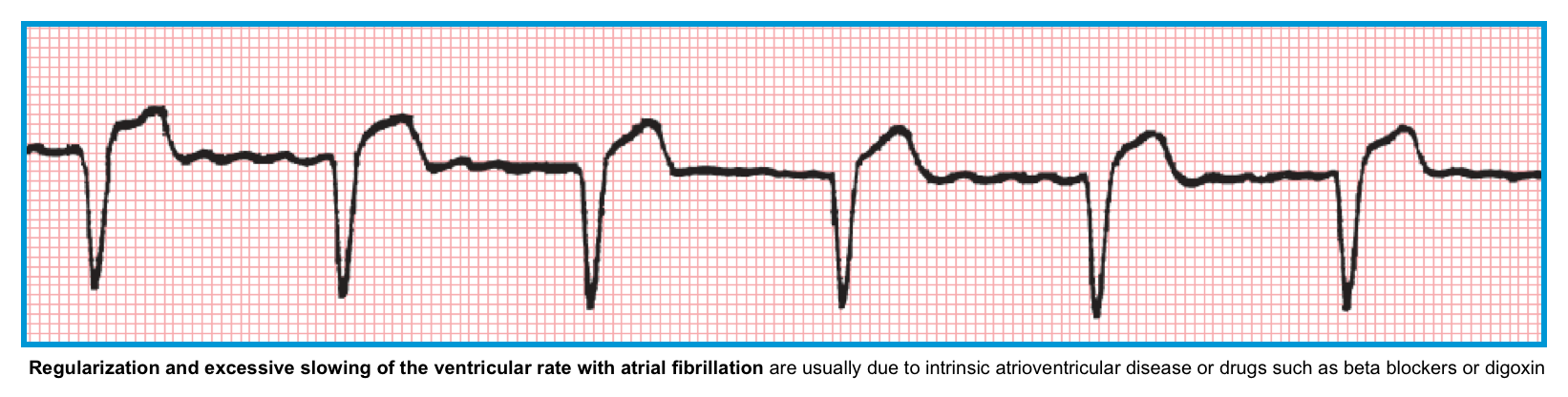

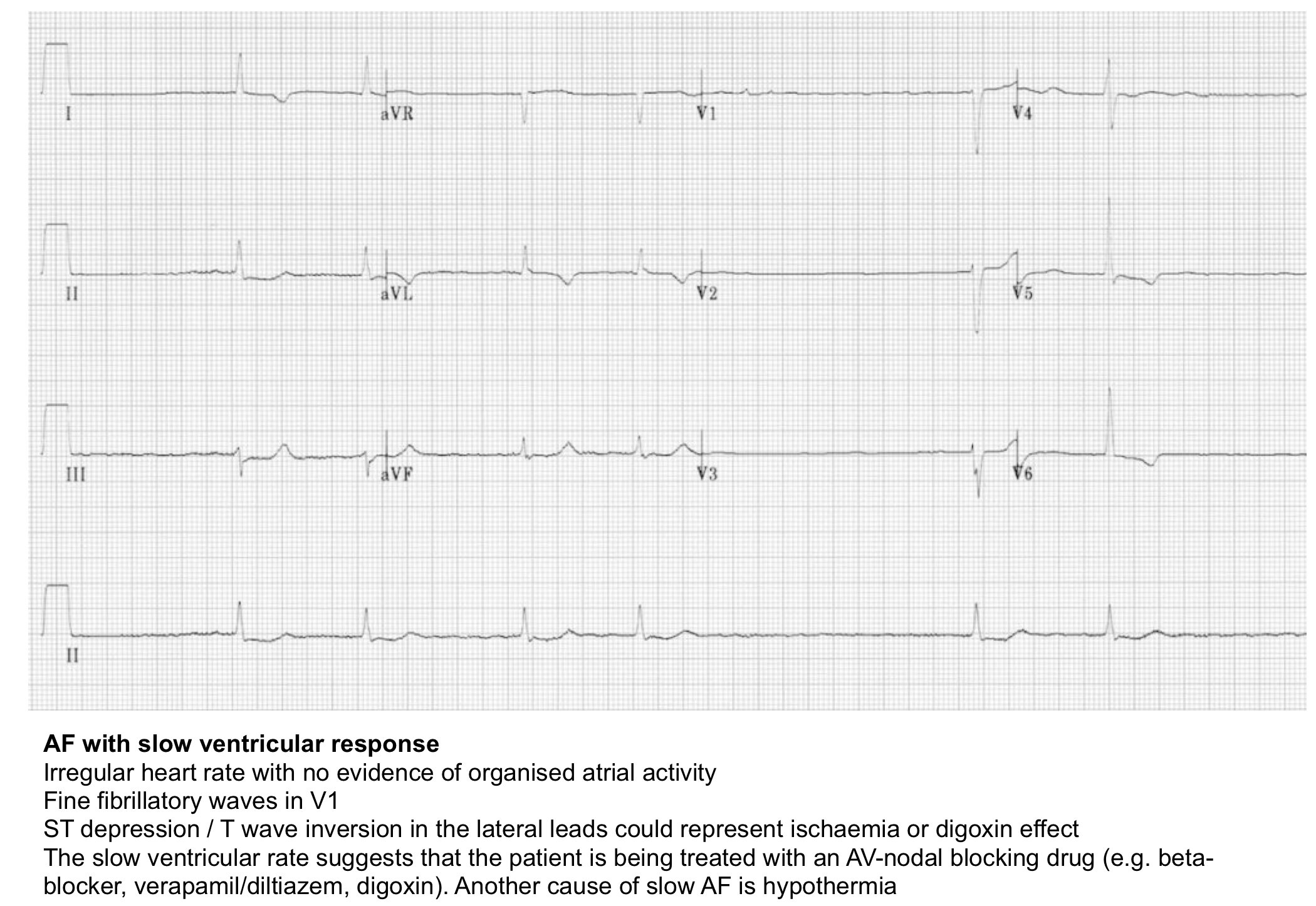

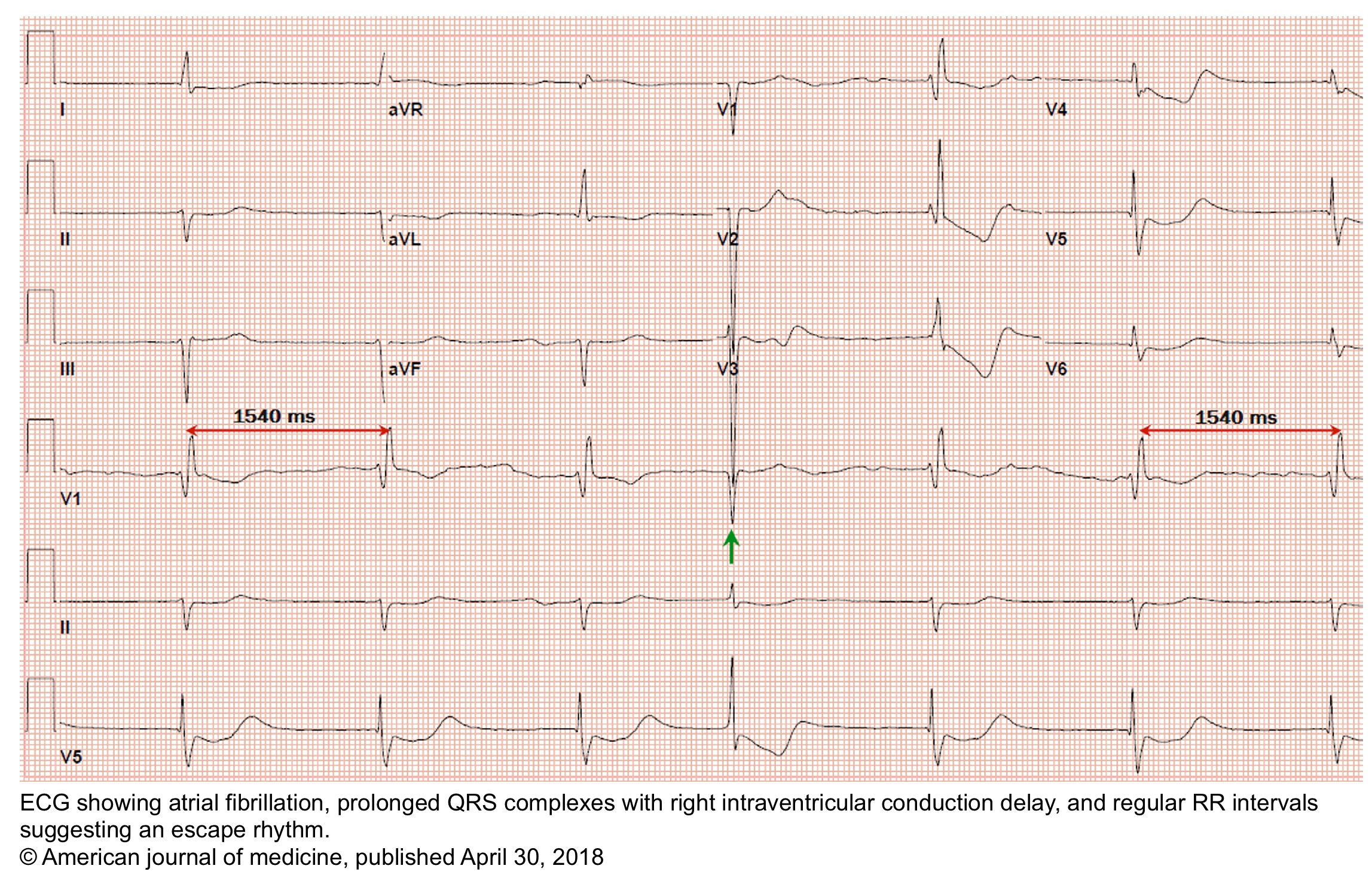

Atrial Fibrillation or Flutter with a Slow Ventricular Rate

New-onset atrial fibrillation (AF), before treatment, is generally associated with a rapid ventricular rate. However, the rate may become quite slow (<50–60 bpm) because of:

- Underlying disease of the AV junction.

- Metabolic, drug effects, or actual drug toxicity:

- Hyperkalemia.

- Drugs that affect AV nodal conduction (e.g., beta-blockers, certain calcium channel blockers, or digoxin)

Regularized AF

- AF is an irregularly irregular rhythm.

- Remember that a rhythm is irregular if the R-R variation in a single cardiac cycle is > 10%

- Regularized AF can be caused by *

- Digoxin intoxication.

- Complete heart block.

⭐️A very slow, regularized ventricular response in AF suggests the presence of an underlying complete AV heart block.

Group beating

Group beating is a pattern of repetitive complexes on an ECG that indicates intermittent AV conduction *.

- Second-degree AVB (either Mobitz I or Mobitz II) *

- Sinoatrial exit block *

- Atrial fibrillation or flutter with variable AV block *

- PACs (atrial bigeminy, atrial trigeminy, etc.) *

- Nonconducted PACs: PACs arriving very early in the cycle may not be conducted to the ventricles at all. In this case, you will see an abnormal P wave that is not followed by a QRS complex (“blocked PAC”). A compensatory pause as the sinus node resets usually follows it.

- Note that in some cases, the P wave may be subtly hidden in the T wave of the preceding beat (producing a notched T wave).

- Conducted PACs: The PACs arriving late in the cycle are conducted to the ventricle, producing a normal QRS complex.

- Nonconducted PACs: PACs arriving very early in the cycle may not be conducted to the ventricles at all. In this case, you will see an abnormal P wave that is not followed by a QRS complex (“blocked PAC”). A compensatory pause as the sinus node resets usually follows it.

Table summary

| Sinus node dysfunction | ECG features | Differential diagnosis |

| Sinus bradycardia | Regular rhythm Ventricular rate < 50-60 bpm QRS complexes are preceded by “sinus” P waves (upright in II, III, aVF) | –Blocked PACs. -SAEB (long cycle is a multiple of the baseline PP interval). |

| Sinus arrest/pauses | Mobitz I: Progressive shortening of PP interval until a P wave is dropped. Mobitz II: Sudden drop of a P wave, without progressive PP shortening. The pause is near multiple of the normal P-P interval. | –Blocked PACs. -SAEB (long cycle is a multiples of the baseline PP interval). |

| Sinoatrial exit block | –Blocked PACs. -SAEB (long cycle is a multiple of the baseline PP interval). | –Atrial bigeminy. |

◾️ECG features of AV conduction disorders are summarized below.

| AV conduction disturbances | ECG features | Differential diagnosis |

| First-degree AV block | PR interval >200 msec (5 boxes). Constant PR intervals. Absence of non-conducted P waves (NCPW). | |

| Second-degree AV block 🟢Mobitz type I block (Wenckebach) 🟠Mobitz type II block | 👉NCPW is present in both types. 🟢Progressive PR prolongation until a beat fails to conduct (NCPW). Group beating is present. 🟠Sudden NCPW without preceding PR prolongation. | -Mobitz I vs II block with 2:1 AVC ratio. -Nonconducted (blocked PACs): P-P is not constant. |

| High-grade AV block | ≧2 non-conducted P waves in a row producing an extremely slow ventricular rate. | -3rd-degree AV block |

| Third-degree (complete) AV block | P-P: Constant. R-R: Constant. PR: Randomly is changing. P-waves run through all phases of the cardiac cycle. Atrial rate > Ventricular rate. Ventricular rate < 45 bpm. | -High-degree Mobitz II. |

Failure of a previously implanted pacemaker

Background

Patients with implantable devices frequently present to the ED. It is important that the emergency physician understand how these devices function, recognize unique related issues, and can treat associated medical conditions. Pacemaker malfunction can lead to brady/tachydysrhythmias as well as other critical conditions, which will be discussed here.

◾️Cardiovascular implantable electronic devices (CIEDs) include:

- Permanent pacemakers (PM).

- Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICD).

- Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) devices.

- Devices capable of a combination of therapies.

◾️Common indication for permanent pacemaker (Class I recommendation)👇 *

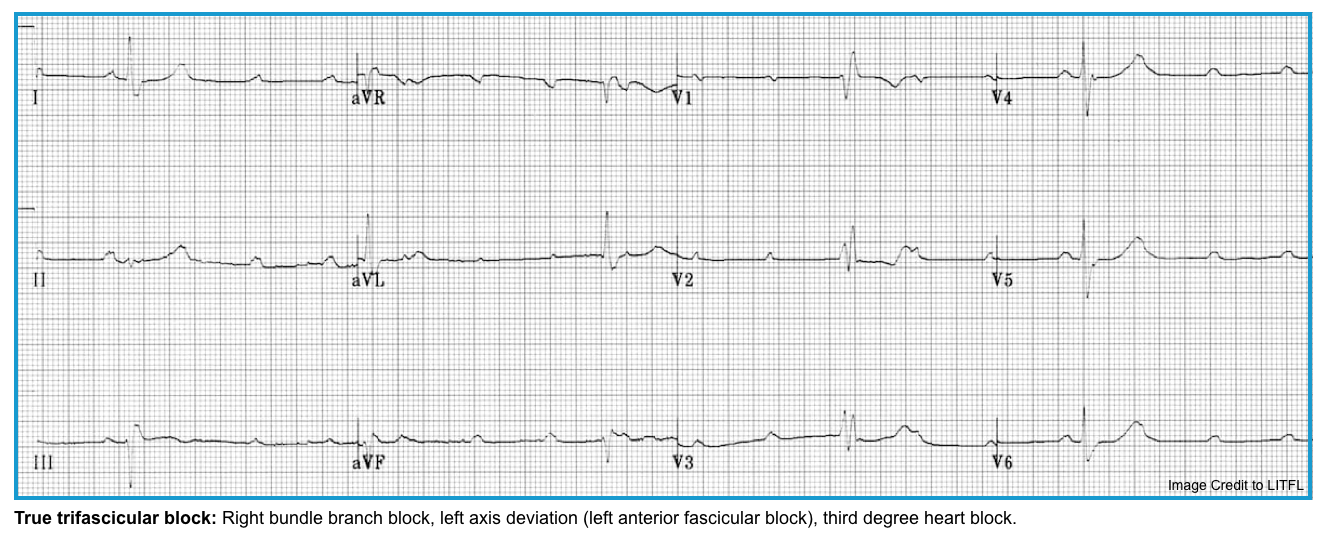

| 1️⃣SND with documented symptomatic bradycardia, including frequent sinus pauses that produce symptoms. 2️⃣Symptomatic sinus bradycardia that results from required drug therapy for medical conditions 3️⃣Permanent pacing is indicated regardless of symptoms in the following conditions (If No Reversible Cause Is Present): ◾️Second-degree Mobitz type II atrioventricular block. ◾️High-grade AV block. ◾️Third-degree AV block. ◾️AV block with evidence of infranodal disease. ◾️If AV block is associated with progressive conduction tissue disorders (e.g., chronic bifasicular block). ◾️True trifascicular block. ◾️Severe systolic heart failure (cardiac resynchronization therapy) |

◾️Components and function

- Main types of pacing

- Single-chamber pacing

- Single-chamber pacing (Atrial)

- Single-chamber pacing (Ventricular)

- Dual-chamber pacing (pacing the right atrium and right ventricle), most commonly used in patients with heart block.

- Biventricular pacing (pacing both right & left ventricles).

- Single-chamber pacing

- Pacemaker Components

- The generator includes the battery and electrodes.

- The PM is powered by a lithium battery with a life span of 5-10 years. The life span is shorter if the pacing requirement is extensive or if the stimulus threshold is high.

- The battery is used to deliver pacing pulses, sensing (analyzing electrical activity in the heart), and storing electrocardiograms.

- The leads: PM lead(s) contain a conductor wrapped in insulation.

- The pacemaker lead tip electrodes can sense the electrical activity of the myocardium and carry the signal to the generator, as well as deliver the electrical stimulus from the generator to the myocardium.

- The tip electrodes are fixed in the myocardium by an electrically active helix or inert lines that anchor the lead.

- The electrodes are separated from the conducting leads by insulation.

- The generator includes the battery and electrodes.

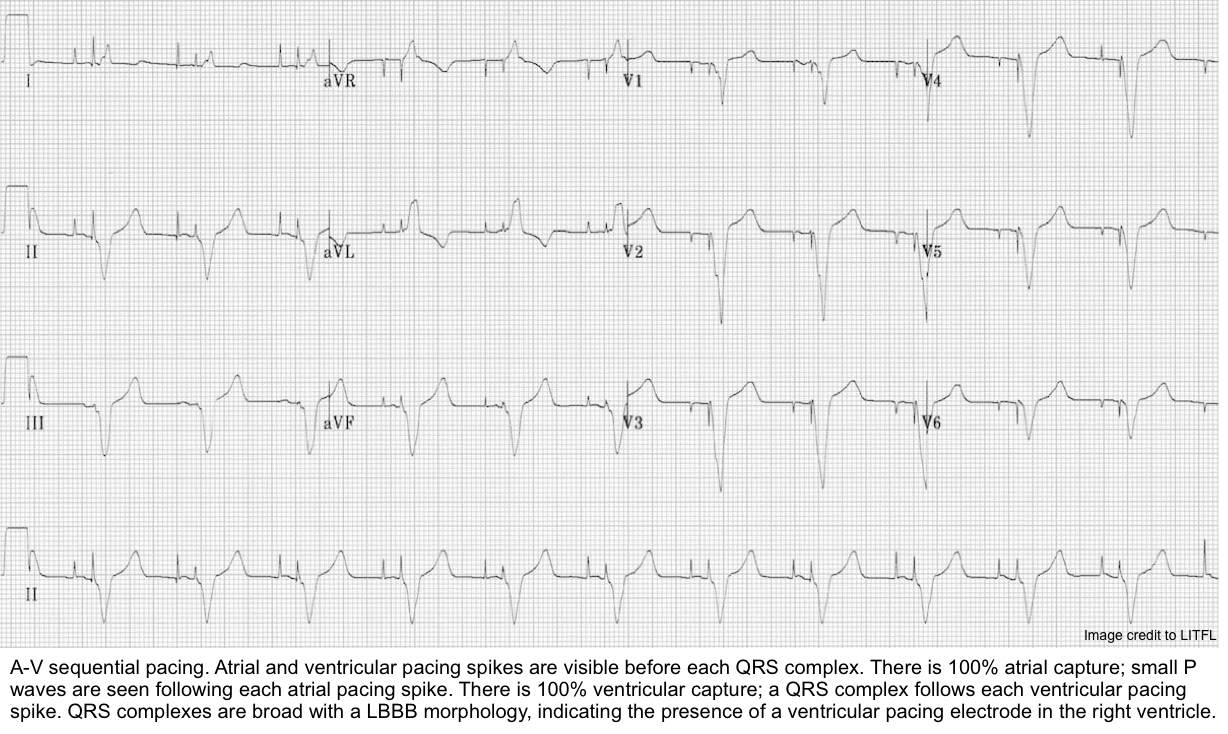

- Atrial pacing in the right atrium produces a “P wave similar to normal sinus rhythm“.

- Spikes before P waves indicate atrial pacing.

- Right ventricular pacing

- Dual-chamber pacing: Spikes are present before both P waves and QRS complexes.

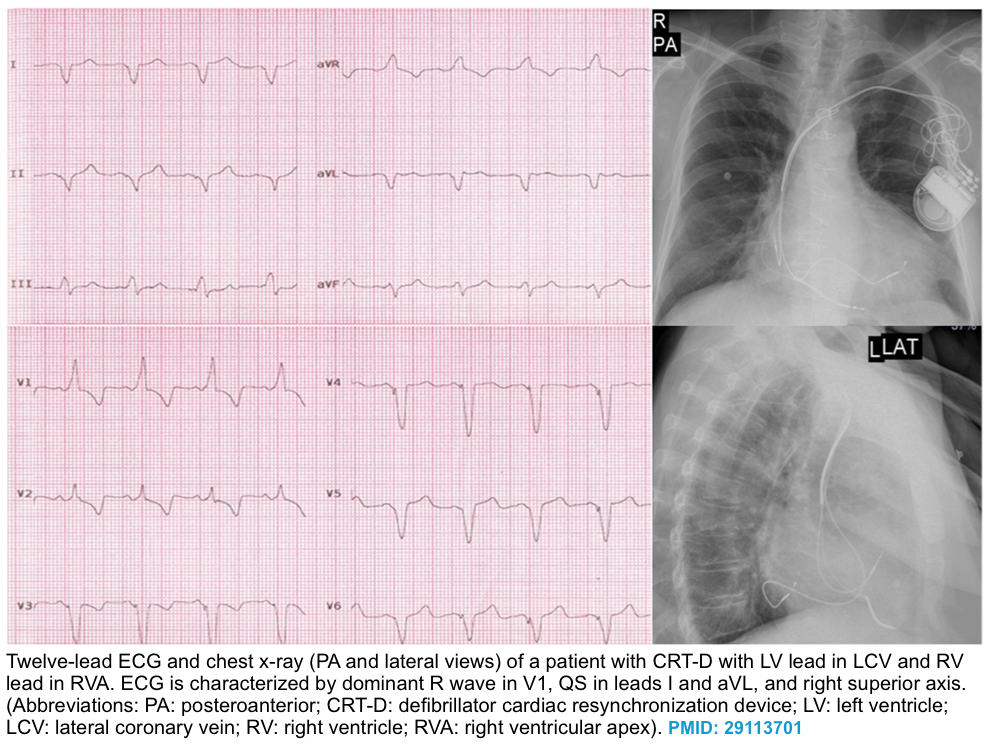

- Biventricular pacing (CRT)

◾️Pacemakers Mode: A 5-letter code has been adopted to identify and classify pacemakers by their lead location and function.

- For the emergency physician, the first 3 letters are of critical importance *.

- The first 3 letters describe the basic functionality of the pacemaker. The pneumonic PASER stands for *:

-

- P: Pacing (the chamber being paced).

- S: Sensing (what chamber is being sensed).

- R: Response to sensing: Inhibit (I), trigger (T), both inhibit and trigger, or dual (D), and no response (O).

-

Inhibit response implies that the pacemaker can be inhibited or suppress its function in the event of native, normal cardiac activity.

-

Trigger means that the pacemaker can be triggered or activated in the absence of native, normal cardiac activity.

-

-

- The fourth and fifth letters express its programmability, rate modulation, and multisite pacing

| Chamber(s) paced | Chamber(s) sensed | Response to sensing | Programmability, rate modulation | Multisite pacing |

| A = Atrium V = Ventricle D = Dual (A + V) O = None | A = Atrium V = Ventricle D = Dual (A + V) O = None | T = Triggered I = Inhibited D = Dual (triggered + inhibited) O = None | P = Simple programmable M = Multiprogrammable C = Communicating R = Rate modulation O = None | A = Atrium V = Ventricle D = Dual (A + V) O = None |

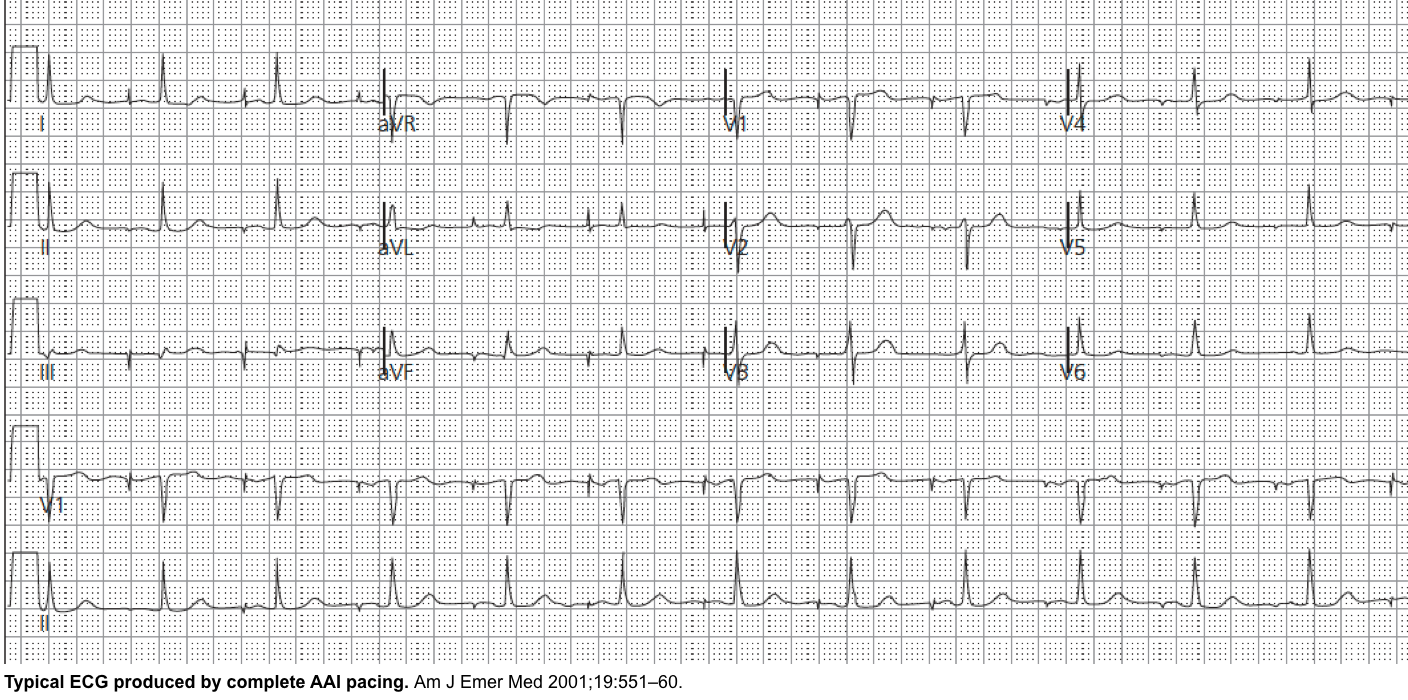

AAI: Atrial pacing and sensing Used in sinus node dysfunction with intact AV conduction.

The right atrium is paced, and if intrinsic atrial activity is sensed, the pacing is inhibited (AAI).

If no native activity is sensed for a predetermined time, then atrial pacing is initiated.

Also termed the atrial demand mode.

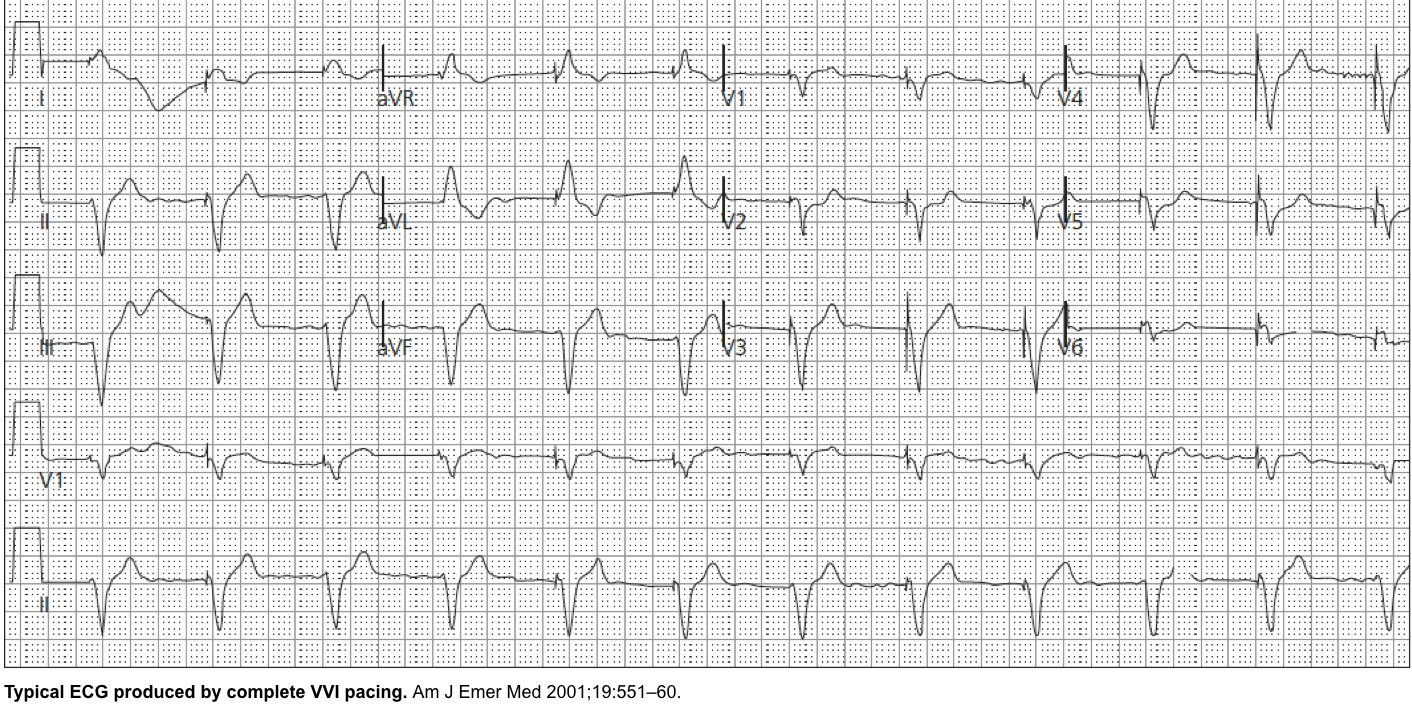

VVI: Ventricle pacing and sensing Used in patients with chronic atrial impairment, e.g., atrial fibrillation or flutter, and slow ventricular response.

The ventricle is only paced, and if ventricular activity is sensed, the pacing is inhibited (VVI).

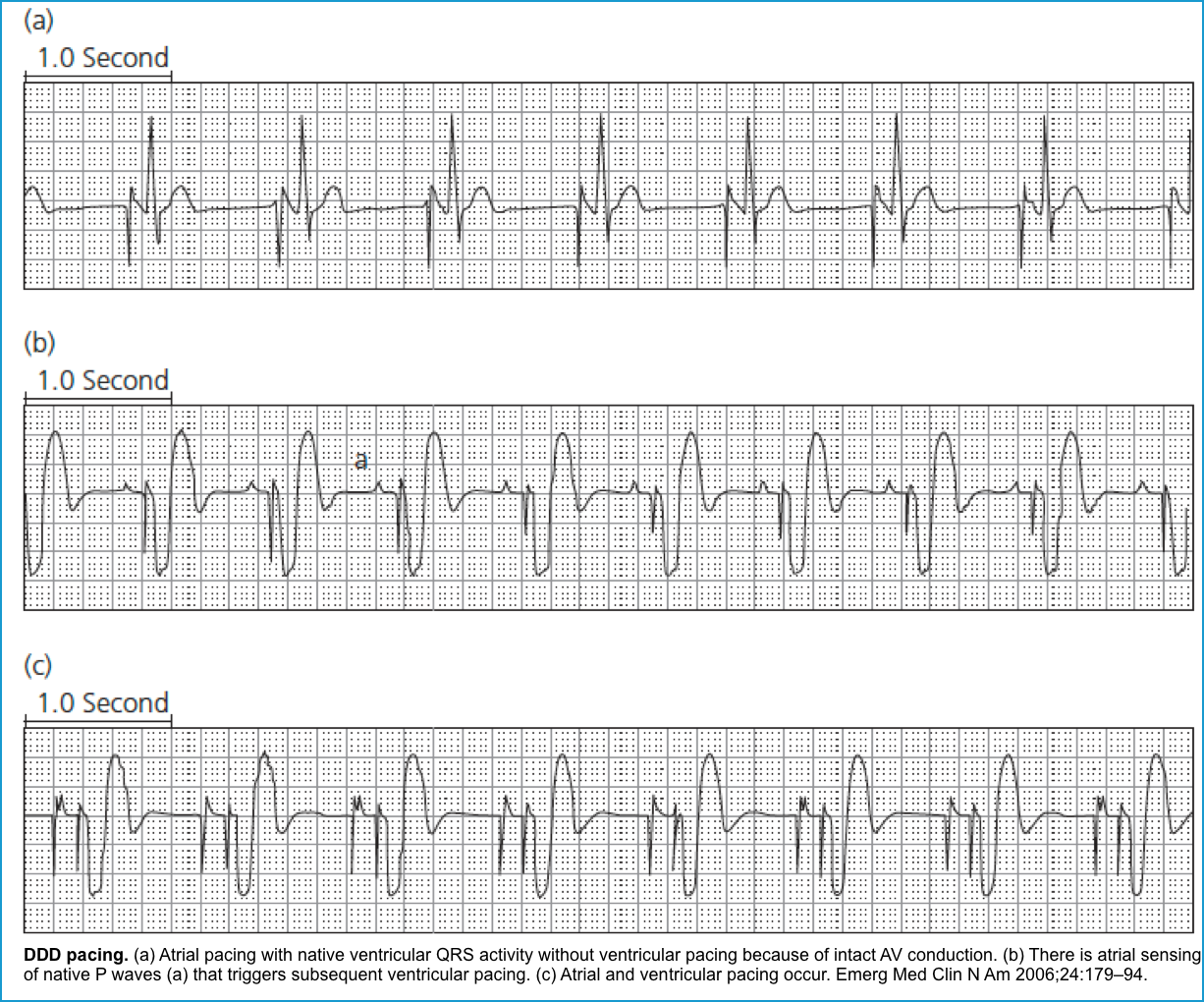

DDD: Pacing and sensing both the atria and ventricles (commonest pacing mode). Atrial pacing occurs if no native atrial activity for a set time. When the PM senses the atrial impulse, the atrial channel is inhibited from delivering an atrial stimulus.

Inhibition of the atrial channel triggers the ventricular channel to deliver a stimulus to the ventricle after a programmed interval. However, if a spontaneous ventricular impulse is sensed, the PM will be inhibited from discharging a stimulus to the ventricle.

- Magnet mode 🧲

-

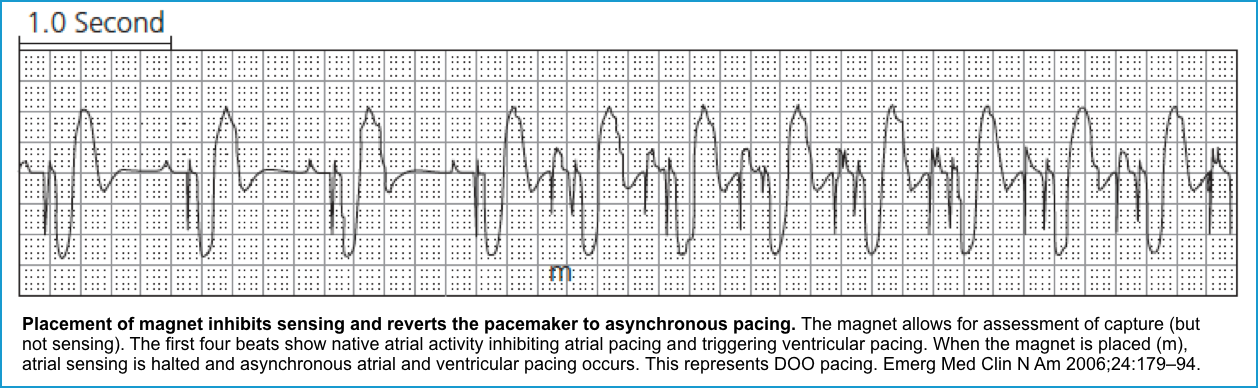

- The magnet mode refers to the response of a pacemaker when a magnet is applied over it.

- Placing a magnet over a pacemaker will turn off the sensing function of the device, placing it in asynchronous mode (e.g, AOO, VOO, or DOO) *.

- Asynchronous modes deliver constant-rate-paced stimuli regardless of the native rate of rhythm.

- In asynchronous modes, the device paces at a rate specific to the manufacturer, which is dependent on the device’s battery life.

- The magnet rate is designed to reflect the degree of battery depletion. This can be the easiest way to test the battery life.

- Reminder:

- Place a cardiac magnet 🧲 on the patient if *:

- Bradycardia and no pacer spikes.

- Bradycardia and slow pacer spikes.

- Pacemaker-mediated tachycardia (160-180 bpm).

- ⚠️In asynchronous ventricle pacing, there is a risk of pacemaker-induced ventricular tachycardia.

- 👉A magnet over an ICD eliminates its anti-tachycardia function (defibrillator deactivation) but does not convert it to asynchronous pacing *.

- Place a cardiac magnet 🧲 on the patient if *:

Implant-related (mechanical) complications

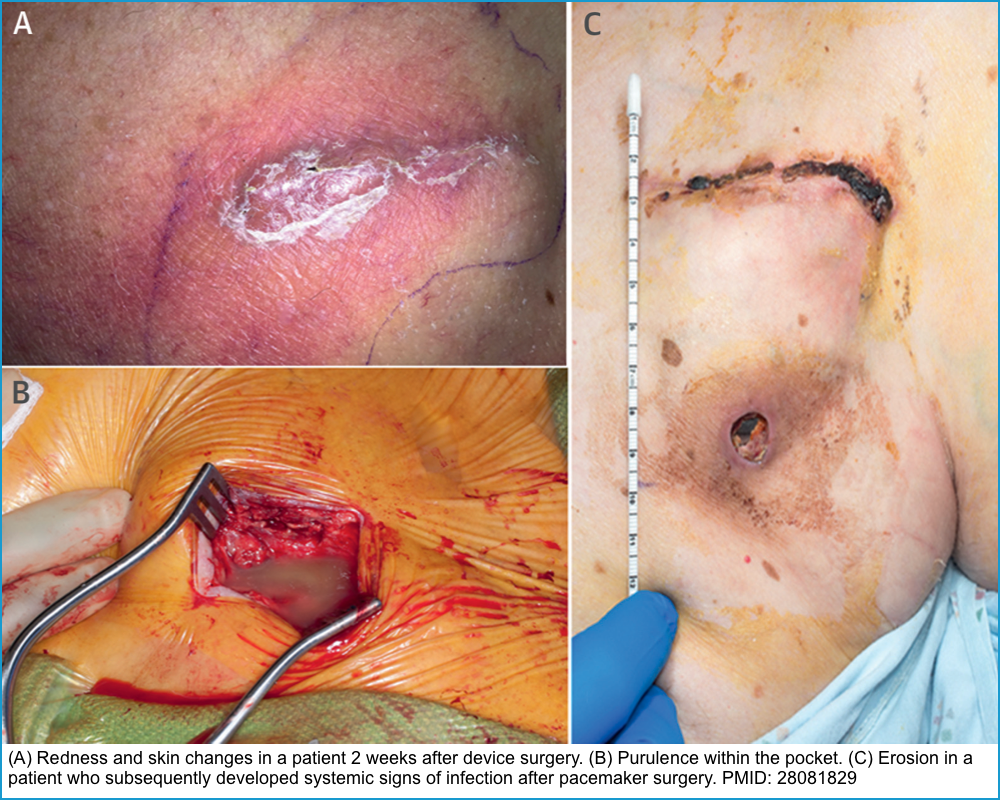

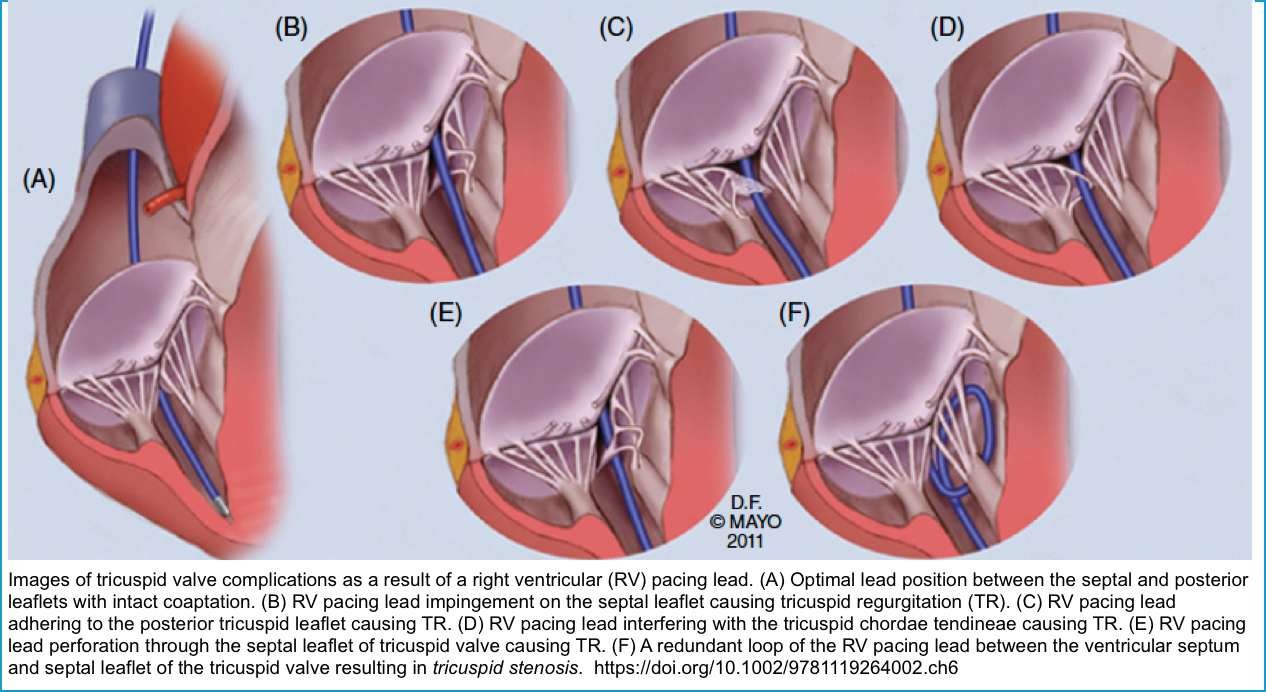

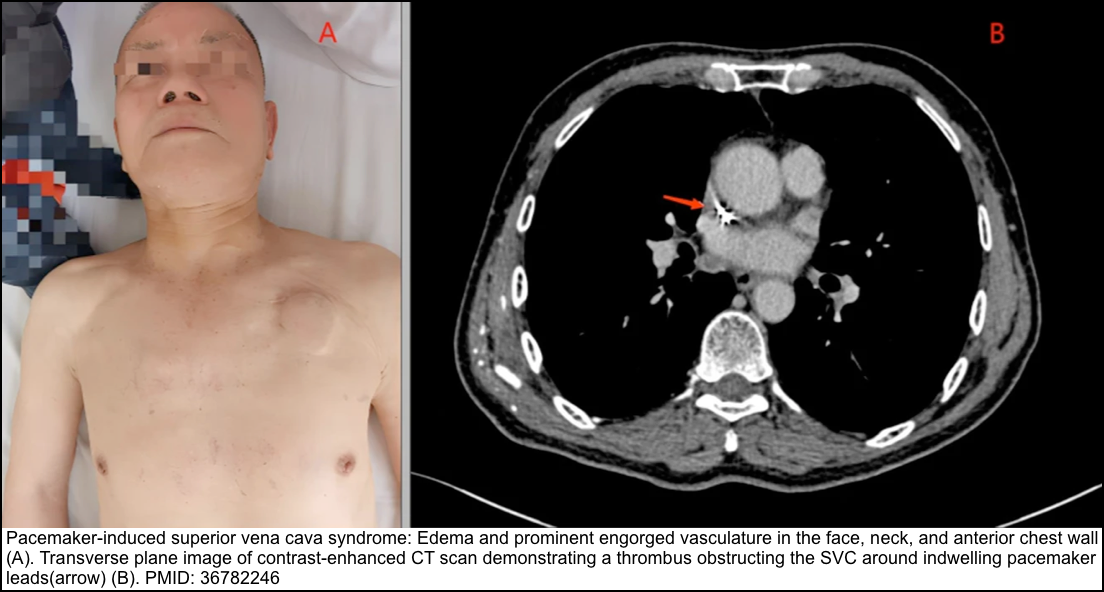

◾️Mechanical complications are summarized in the following table *.

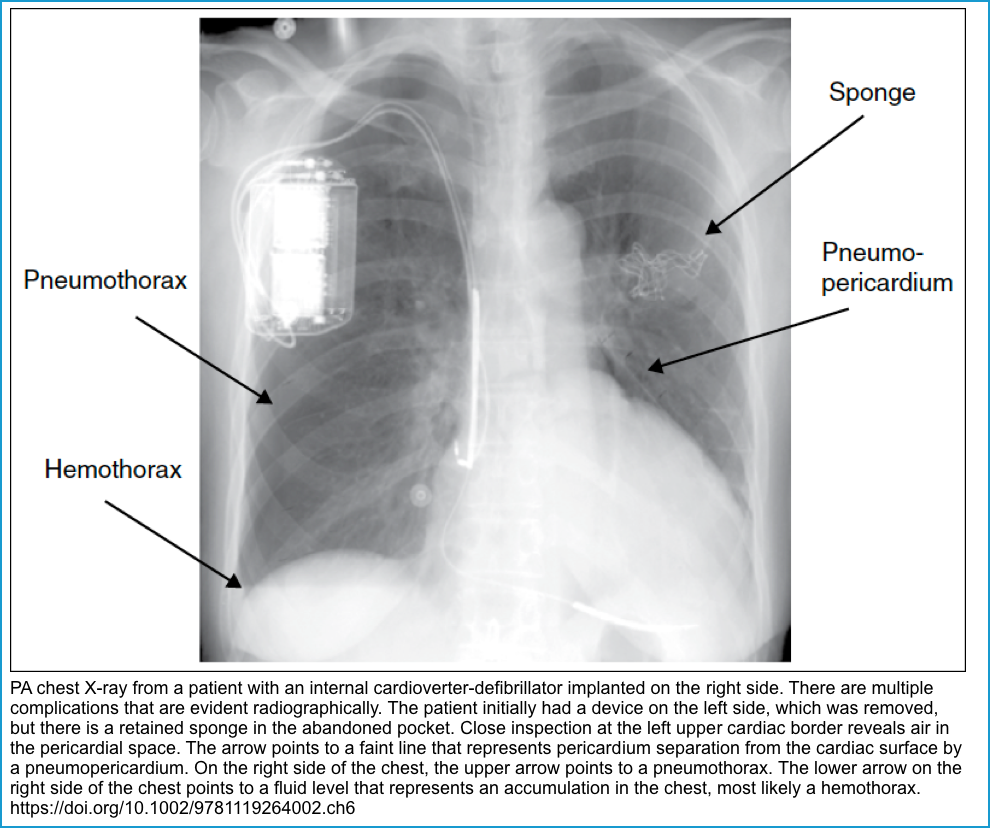

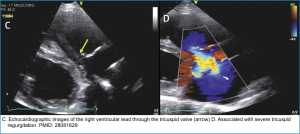

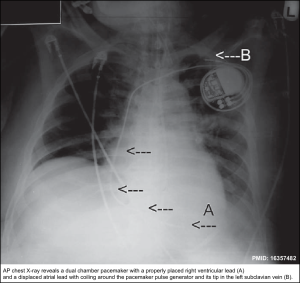

| Implant-related complication | Clinical manifestation | Diagnosis Method | Management |

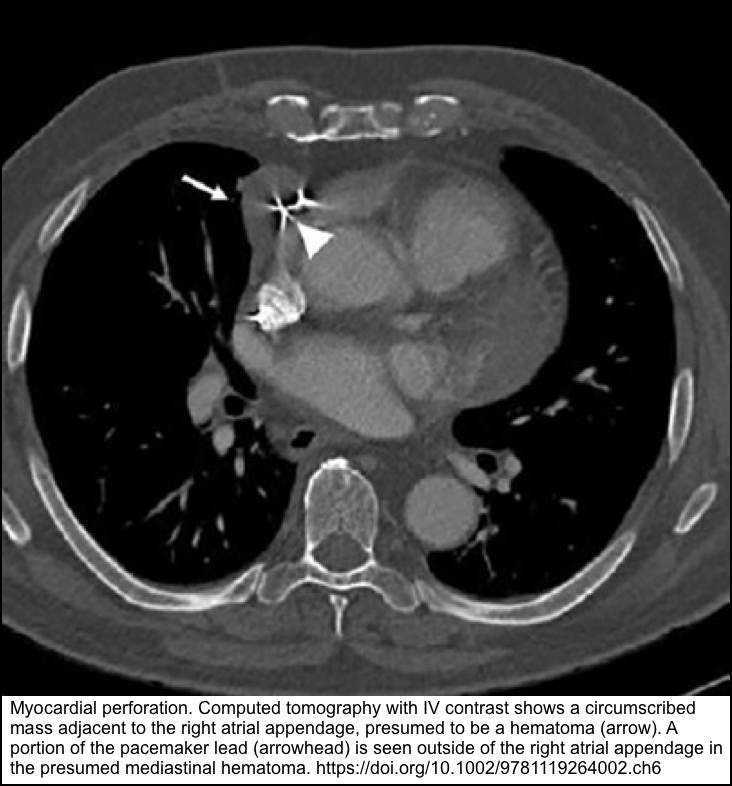

| Cardiac perforation | Typical presentation is chest pain, dyspnea, syncope. ECG: Low voltage or electrical alternans. POCUS: Pericardial effusion , Signs of Tamponade | Echocardiography CT | Pericardiocentesis, lead withdrawal and repositioning |

| Pocket hematoma | Echymosis and swelling at pocket site. | Examination | Conservative (rarely, surgical evacuation). ⛔️Aspiration of pocket should be avoided *. |

| Pocket infection | Pain, swelling, erythema, purulent discharge, dehiscence, erosion or necrosis of the pocket site * | Examination | Device removal with lead extraction and antibiotics. |

| Systemic infection Endocarditis | Fever, chills, can progress to sepsis and septic shock +/- Clinical signs and symptoms of endocarditis +/- Vegetation on echocardiography. +/- Positive blood and lead tip cultures | Echocardiography Blood cultures TEE | Device removal with lead extraction and antibiotics. |

| Lead Fracture | Failure to sense/pace, and loss of capture. | CXR, ECG | Lead revision/ device replacement. |

| Lead dislodgement (1) | Undersensing, loss of capture, or inappropriate pacing Bradycardia due to faulty pacing, or failure to detect and shock VT/VF. Exacerbation of heart failure symptoms. Complication: ↑Risk of infection, thrombosis, perforation. | CXR Telemetry ECG | Treat presenting tachy-or-bradydysrhythmia Repositioning or replacement of the lead |

| Venous thrombosis | Signs are often absent, but There may be typical manifestations of acute DVT and even SVC syndrome. | Sonography/venography | Anticoagulation, angioplasty, or surgery |

| Pneumothorax, hemothorax | May be asymptomatic, pleuritic chest pain, dyspnea to respiratory distress | Chest radiography | Conservative or aspiration/thoracostomy |

| Tricuspid regurgitation | Asymptomatic, or Signs of right-heart failure (RHF). | Echocardiography | Medical management of symptomatic RHF. Lead extraction and/or annuloplasty/valve replacement |

(1)Twiddler’s syndrome is a specific subtype of lead dislodgment.

Image gallery

Pacemaker Malfunction

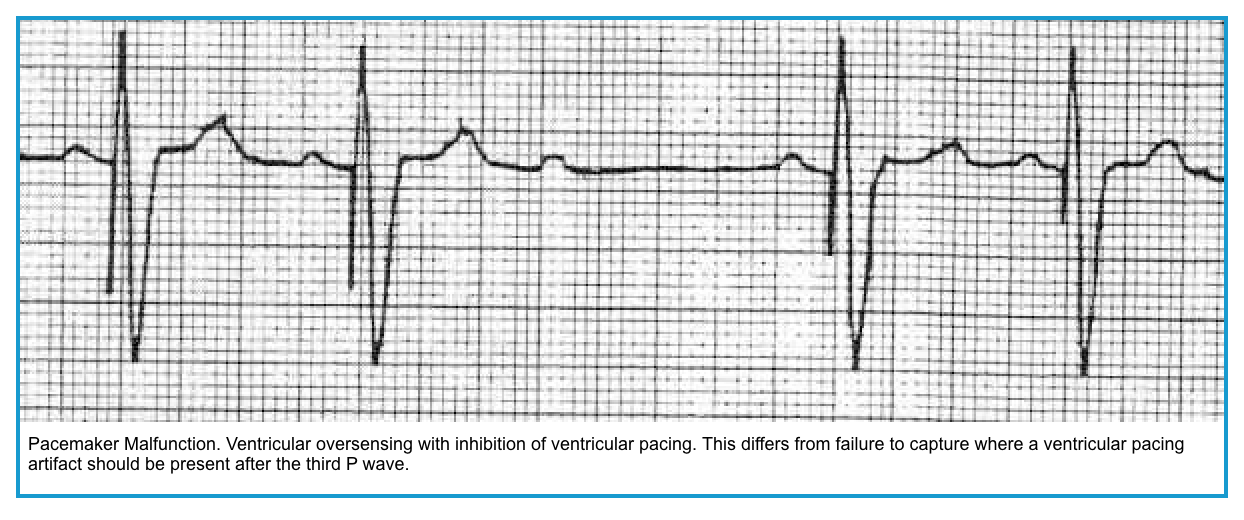

◾️Definition and classification

- Pacemaker malfunction refers to any deviation from the normal function of the pacemaker (i.e., dysfunctional pacing, sensing, capturing, or rate) *.

- Traditionally, pacemaker malfunction is classified into 3 categories: Failure to pace, failure to capture, and failure to sense.

- ⭐️However, this traditional categorization has little value in the acute setting (esp. in critical patients), because the etiology of each class of PM-malfunction overlaps greatly.

- Therefore, all patients with suspected pacemaker malfunction are managed similarly in an acute care setting until the cause can be identified by device interrogation.

◾️Etiology of pacemaker malfunction

- Regardless of the type of malfunction, the causes of PM malfunction can be broadly related to:

- Mechanical (implant-related) complications (e.g, lead dislodgement or fracture) are explained above.

- Electrical complications, such as dead battery, improper programming, myocardial threshold changes (due to ischemia, electrolyte abnl, etc).

◾️The most common clinically significant pacemaker malfunctions include *:

- Failure to pace

- Failure to capture

- Failure to sense (or undersensing)

- Pacemaker-mediated tachycardia

- Twiddler’s syndrome

- Pacemaker syndrome.

◾️Table. ECG and other helpful clues to diagnose the type of pacemaker malfunction *

| Pacemaker malfunction | ECG clues and other features |

| ▪️Failure to pace | 💡Absence of pacing spikes (where it is expected). 🧲Application of a magnet yields no pacing spikes |

| ▪️Failure to capture | 💡Pacer spikes are seen but without subsequent P or QRS waves. 🧲Application of magnet shows regular pacing spikes, but without 100% capture |

| ▪️Failure to sense (or Under-sensing) | 💡Inappropriate pacer spikes (spikes within native QRS complex, or ST-T segment) |

| ▪️Pacemaker-mediated tachycardia | 💡A rapid, regular ventricular-paced rhythm. 💡Ventricular rate is less than the maximum upper rate of the pacemaker (usually 160-180 bpm). 🧲Stops with magnet placement |

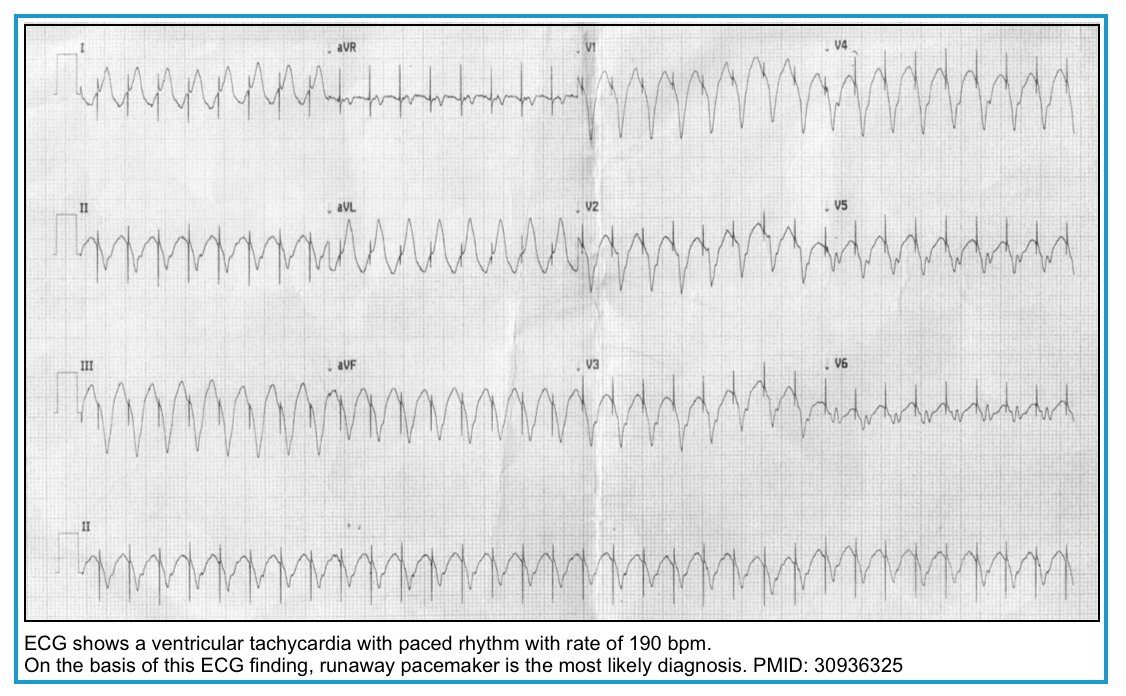

| ▪️Runaway pacemaker | 💡Pacer spikes are seen but without subsequent P or QRS waves. 💡Ventricular rate is greater than programmed upper limit of the device *. 🧲Application of magnet shows regular pacing spikes but without 100% capture |

| ▪️Pacemaker syndrome | 💡ECG: Retrograde P waves following RV-paced QRS complexes. 💡Cannon A Wave (Loss of atrioventricular synchrony) |

General approach to pacemaker malfunction in ED

◾️Key points

- The traditional categorizing of pacemaker malfunction (i.e., failure to pace/sense/capture) neither determines the work-up nor aids in the emergency treatment of device malfunction in the acute care setting *. The focus needs to be on correcting hemodynamic instability.

- 💡No matter the cause of pacemaker failure, ED management is dictated by the patient’s symptoms and hemodynamic status *.

- In the absence of hemodynamic compromise, early “Device Interrogation” and admission to a monitored setting are appropriate.

◾️Emergency department evaluation *

- History

- Medication list?

- Comorbidities?

- Original indication for pacemaker placement?

- Type of pacemaker?

- Obtain an ID card to identify the type and model of a pacemaker.

- Dates of implantation and revision, if and when programming changes were made.

- Exposure to any electromagnetic interference (MRI, electrocautery, or radiation therapy), or blunt trauma?

- Symptoms. Ask for pacemaker-related malfunction symptoms, including:

- Symptoms of ↓perfusion or heart failure: Fatigue, dizziness or syncope, or exertional dyspnea, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, and edema?

- Palpitation? Chest pain? Muscle twitching?

- Physicals

- Standard cardiopulmonary exam. Possible physical findings:

- Heart

- Tachydysrhythmias, bradydysrhythmias.

- Muffled heart sounds or rubs in the setting of effusion.

-

Murmurs in the setting of endocarditis.

-

S3 or S4 in the setting of heart failure.

- Lung

-

Absent breathing sounds in the setting of pneumothorax.

-

Wheezes or rales in the setting of heart failure.

-

- Extremities:

- Heart

- Examine the pocket site for signs of infection or swelling.

- Signs of infection include redness, pain, fluctuance, purulent discharge, dehiscence, erosion, or necrosis of the pocket site *

- Standard cardiopulmonary exam. Possible physical findings:

- ED investigations

- A 12-lead ECG.

- Is there an unstable bradycardia?

- The morphology of paced QRS complexes provides useful information (see above).

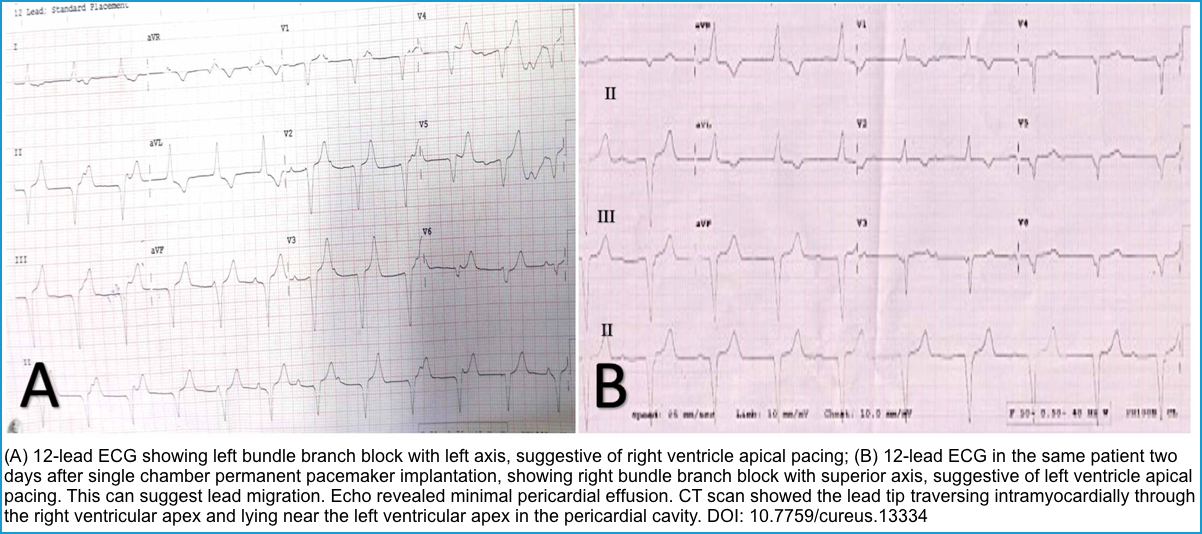

- Compare it to prior ECGs, looking particularly at axis changes. In patients with RV pacing, a normal ECG looks like LBBB.

- RBBB ECG pattern in these patients can suggest “Lead Displacement”, “Perforation of Septum”, or a “Fractured Lead” *. Figure below.

- Compare it to prior ECGs, looking particularly at axis changes. In patients with RV pacing, a normal ECG looks like LBBB.

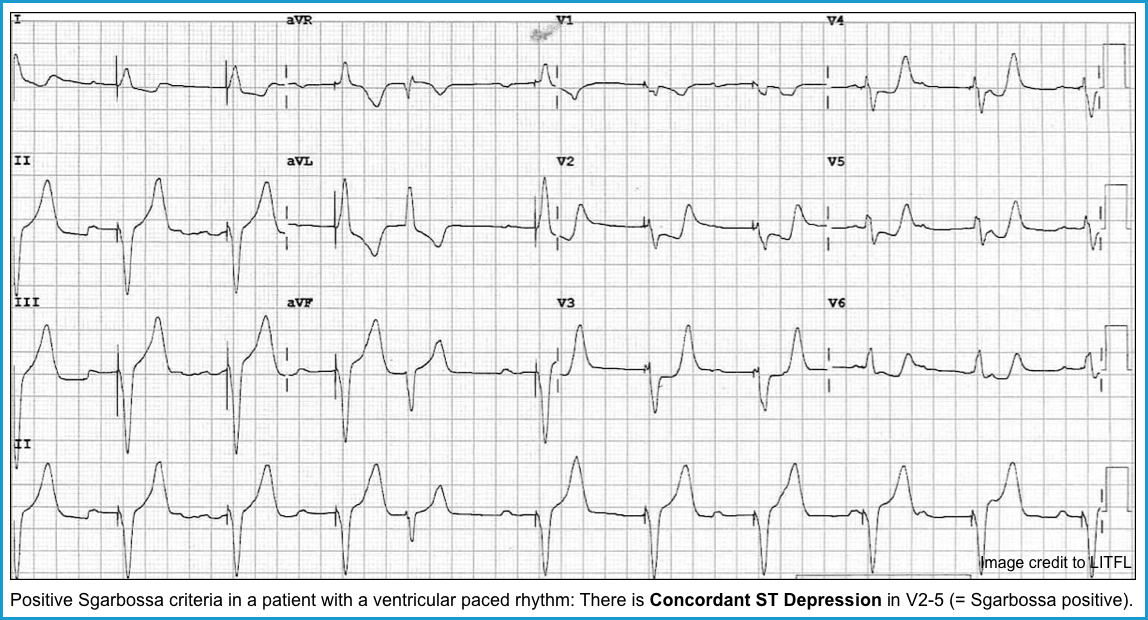

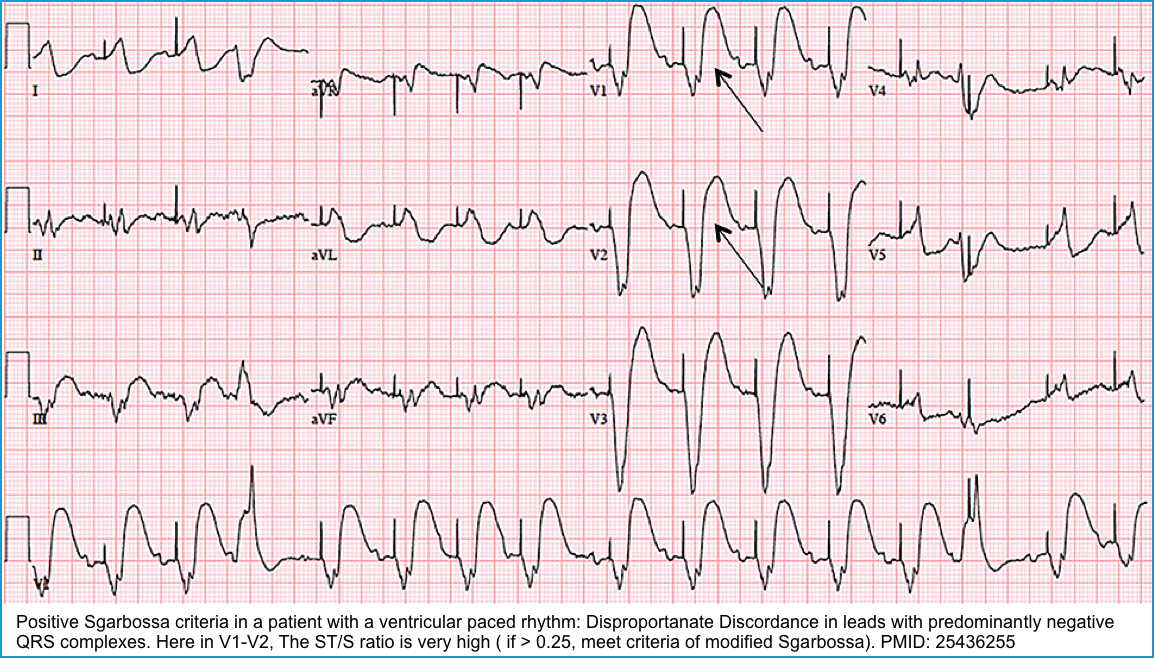

- The ST-T should be discordant with QRS. If not, suspect acute myocardial infarction. Figure below.

- A 12-lead ECG.

| To diagnose “Acute Myocardial Infarction” in pacemaker patients, employ Sgarbossa’s Criteria (MDCalc) * |

-

- Labs

- Troponin (depending on the history and clinical presentation) *.

- Electrolytes, including Ca, Mg.

- Electrolyte abnormalities (especially hypo/hyperkalemia) can result in pacemaker malfunction, particularly failure to capture (more on this, below).

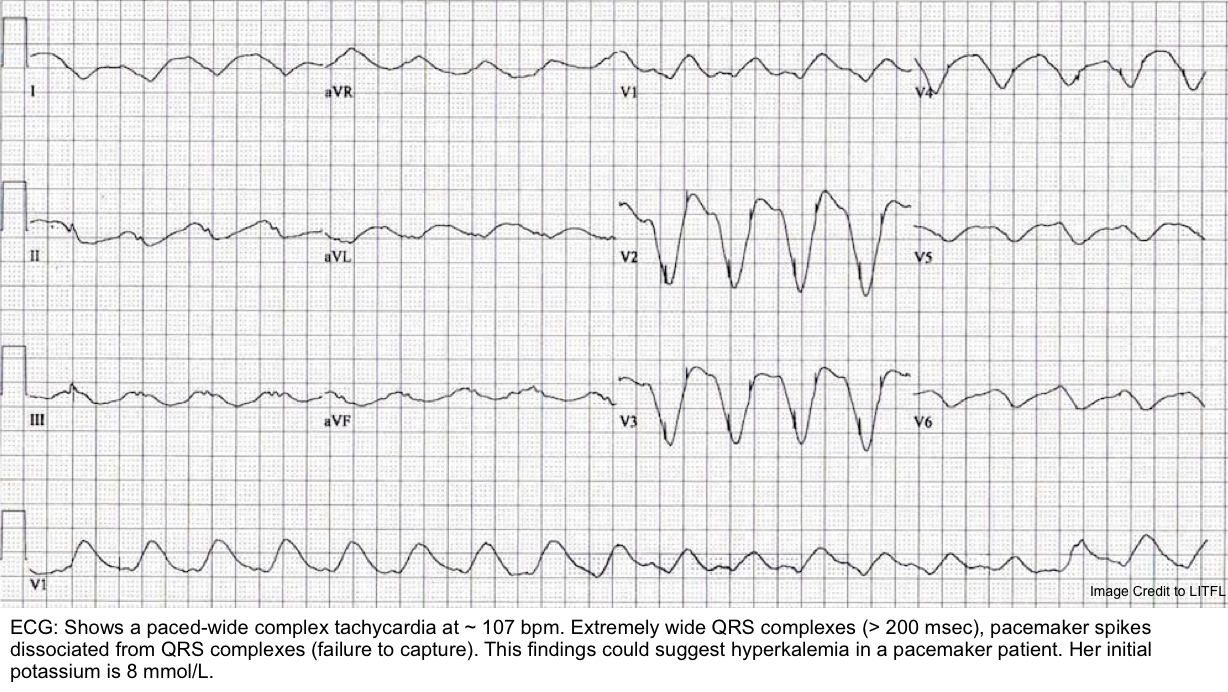

- In pacemaker patients, hyperkalemia causes widened paced-QRS complexes fused with tall T waves, similar to a sine wave pattern.

- Electrolyte abnormalities (especially hypo/hyperkalemia) can result in pacemaker malfunction, particularly failure to capture (more on this, below).

- Serum cardiotoxic drug levels with rapid turnaround, like phenytoin, digitalis.

- Labs

-

- Imaging

- Obtain a chest X-ray assessing for device manufacture, lead fracture/displacement, and pneumothorax.

- A CXR can reveal useful information, including:

- A radio-opaque code from which the model number and manufacturer can be obtained.

- Lead location and integrity, such as lead dislodgment, migration, or fracture, can also be seen.

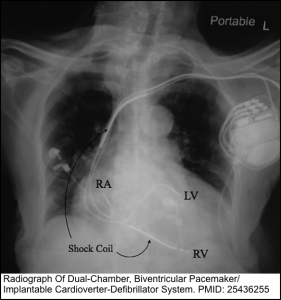

- The key to differentiating a permanent pacemaker from an ICD is the presence of shock coils, which appear as thick bands on the leads *. Figure below.

- Presence of possible complications of implantation, such as pneumothorax, hemopneumothorax, myocardial perforation, and improper seating of a connector pin. The winding of a lead around the pulse generator may be indicative of twiddler syndrome (more on this below).

- A CXR can reveal useful information, including:

- Obtain a chest X-ray assessing for device manufacture, lead fracture/displacement, and pneumothorax.

- Imaging

-

- Bedside echo looking for wall motion abnormality, pericardial effusion w/wo tamponade physiology *.

- If a pocket infection is suspected

- Computed tomography (CT) to identify the presence and depth of pocket infection.

- Blood cultures.

| Management of Critical Patients in ED |

🟥Patients in cardiac arrest

- Follow ACLS protocol according to AHA guidelines. A few extra considerations are advised:

- If defibrillation is needed, place the pad in an anterior-posterior position *.

- Place the pads at least 10 cm away from the pacemaker unit.

- After defibrillation, the pacemaker should be interrogated and, if needed, reprogrammed.

🟥Unstable Pacemaker-dependent patients

- Place on a cardiac monitor and obtain a 12-lead ECG ❤️〰️

- Rapid IV access.

- If central venous access is required, consider placement in the femoral veins to avoid interference and complications associated with pacemaker wires in the subclavian vein and superior vena cava *.

- Unstable Bradydysrhythmia

- Follow the standard ACLS protocols *.

- Be prepared!

- Place transcutaneous pacing (TCP) pads.

- Be prepared for emergent transvenous pacing (TVP).

- ED physicians should recognize that one cause of pacemaker failure leading to bradycardia can be managed by placing a cardiac magnet *.

- 🧲Place a Cardiac Magnet over the PM pocket.

- If Unresponsive to the magnet, proceed with:

- Atropine 0.5 mg IV push q3-5min (max 3 mg).

- Epinephrine 2-10 µg/min

- Transcutaneous pacing

- If Unresponsive to TCP, emergent transvenous pacing (TVP) might be necessary *.

- Treat underlying electrolyte disorders.

- Involve the Cardiologist early.

- Unstable Tachydysrhythmias

- Follow the standard ACLS protocols *.

- If external cardioversion or defibrillation is needed, do not place the pads directly over the device*.

- Try to place the pads at least 10 cm away from the pacemaker unit.

- Treat underlying electrolyte disorders.

- Involve the Cardiologist early.

- If Pacemaker Mediated Tachycardia (PMT)

- If Runaway Pacemaker:

- Unstable pacemaker-dependent patient related to mechanical complications of the device

- The ED physicians should be familiar with implant-related complications (see here).

- Emergent Pericardiocentesis in Crashing Patients with Tamponade.

- Tube thoracostomy for hemodynamically significant pneumothorax/hemothorax.

- Start broad-spectrum antibiotic, including vancomycin for lead infection/vegetation and pocket infection *.

- Start anticoagulation with heparin or enoxaparin for pacemaker lead-induced thrombophlebitis *.

- Consider interventional radiology consultation for possible catheter-directed thrombolysis *.

- The ED physicians should be familiar with implant-related complications (see here).

Subcostal view. RV free wall perforation by the pacemaker lead. Pericardial effusion with echocardiographic signs of tamponade present. PMID: 24403395

Device Malfunction

Abnormal sensing

◾️Normal sensing: Intrinsic beats are sensed and inhibit the pacemaker.

◾️Abnormal sensing. This may occur due to undersensing (or failure to sense) and oversensing.

Failure to sense (or Under-sensing)

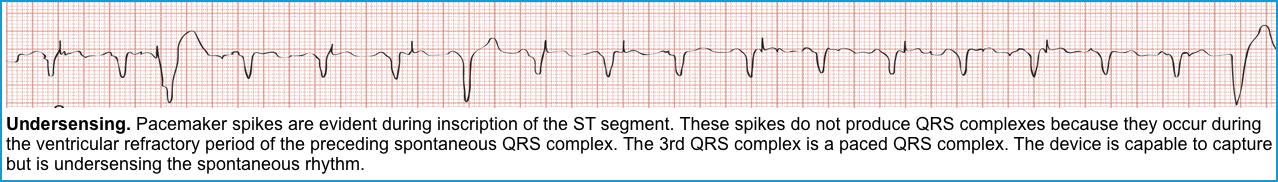

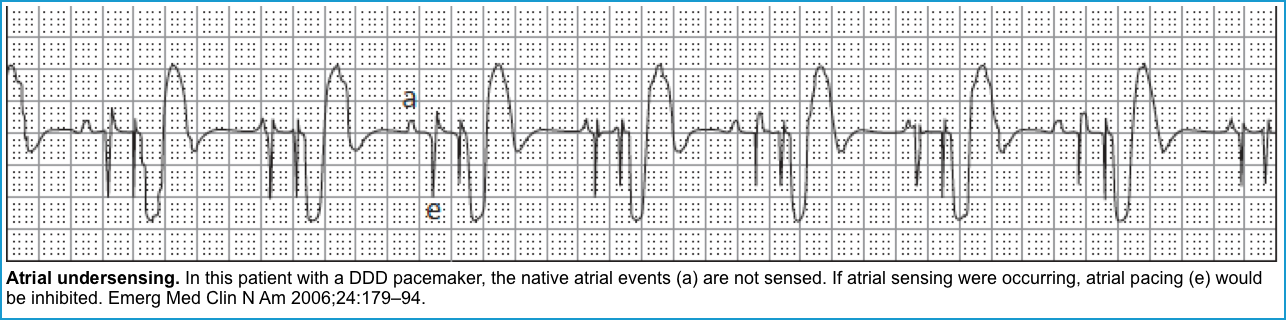

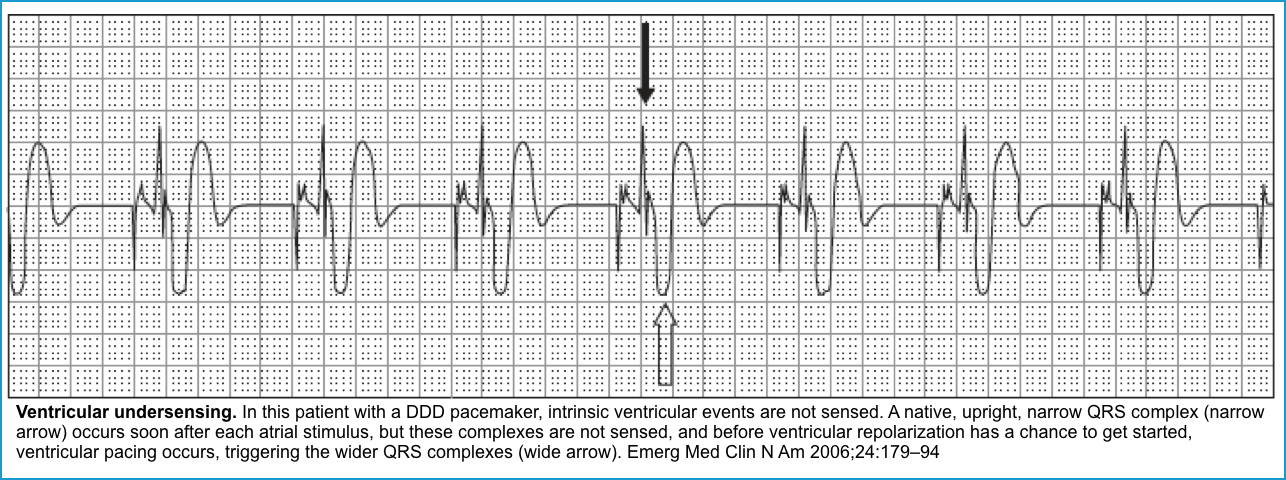

◾️This occurs when the pacemaker fails to sense native cardiac activity, resulting in overpacing, with a risk of R-on-T phenomenon and ventricular arrhythmia *.

- Undersensing may lead to overpacing.

◾️ECG (Figures below).

- Presence of PM spikes despite native beats (a native P or QRS wave preceding a pacer spike).

- Depending on when the pacer spikes occur, capture may or may not happen.

- Pacer spikes are seen during the refractory period (ST-T) segments but do not result in capture.

- An ECG with pacemaker spikes within native QRS complexes also suggests undersensing.

- Depending on when the pacer spikes occur, capture may or may not happen.

- Media 🎥

◾️Causes

- Processes that result in a change in the amplitude, vector, or frequency of the native signal, including:

- Ischemia

- New bundle branch blocks

- Premature ventricular complex (PVC)

- Ventricular or atrial dysrhythmias

- Electrolyte abnormalities, esp. hyperkalemia

- Problems that make the lead incapable of carrying the signal from the myocardium to the PM generator:

- Lead dislodgement, or fracture.

- Insulation problems

- Low current from a failing battery

- Tissue damage at the interface of the electrode and myocardium. This can be caused by external cardiac defibrillation.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) side effects.

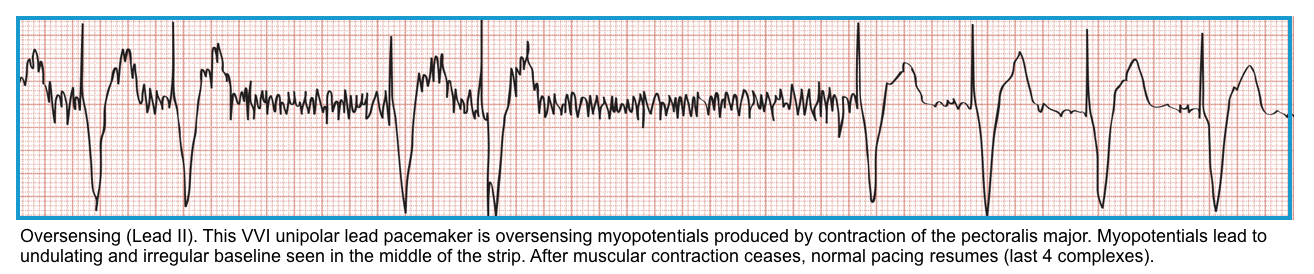

Oversensing

- The PM sensor interprets external stimuli as native cardiac activity, leading to inappropriate pacing inhibition *.

- Oversensing may lead to underpacing.

- 👉This can be stopped by a magnet 🧲.

- Oversensing occurs when electrical signals are inappropriately recognized as native cardiac activity, and the pacing is inhibited.

- These inappropriate signals may be large P or T waves, skeletal muscle activity, or lead contact problems.

- This occurs when a pacer is too sensitive or has inappropriately set refractory periods.

- ECG

- Episodes can be intermittent, manifested by irregular pacemaker function, including reoccurrence of the patient’s underlying bradycardia; or

- They can be constant, with either absent pacing or a decreased pacing rate.

- Media 🎥

- Causes

- Large P, T, or U waves.

- Skeletal muscle myopotentials, tremors that are incorrectly interpreted as QRS complexes.

-

Diaphragmatic contractions during the hiccups

-

Electromagnetic interference (ie, MRI, smartphones)

- Electrical signals are produced by intermittent metal-to-metal contact.

- Lead fracture, dislodgement, or loose connections within the pacemaker generator itself can cause these abnormal signals.

- Electrocautery, MRI, and extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy.

- ⭐️Note that oversensing is rarely due to the failure of the generator.

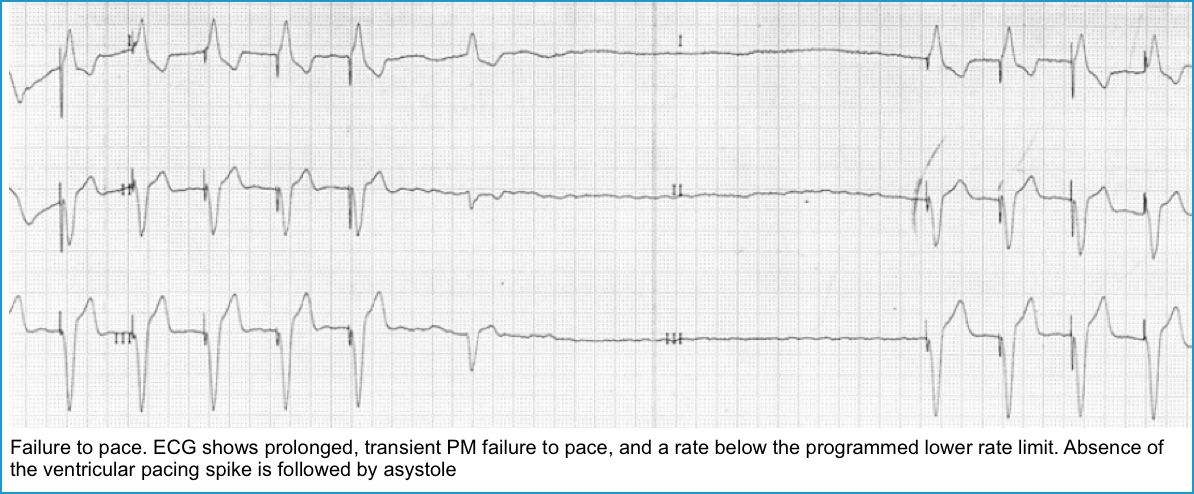

Failure to pace

Pacing spikes: Are they present and appropriate?

◾️Normal pacing can include the appropriate presence of spikes or appropriate lack because of sensing intrinsic beats.

◾️Failure to pace (missed beats): Defined as the failure of the PM to deliver an electrical stimulus to the heart.

◾️ECG: Absence of pacemaker spikes on a 12-lead ECG *.

- Failure of an atrial lead to pace will result in the absence of atrial spikes.

- Failure of a ventricular lead to pace will lead to the absence of ventricular spikes.

◾️Causes *

- Oversensing (most common). See above.

- The pacemaker is inappropriately inhibited by external signals,

- ⭐️Applying a magnet turns off sensing to differentiate between over-sensing from battery depletion.

- Lead failure

- This has a higher risk of occurring in the setting of trauma, sharp turns in the generator pocket, tight sutures, or movements that can lead to pulling of the insulation or lead itself.

- Lead fracture or dislodgement prevents delivery of the electrical stimulus from the PM generator.

- Battery end-of-life.

- Component failure (usually due to blunt trauma).

- Electromagnetic interference

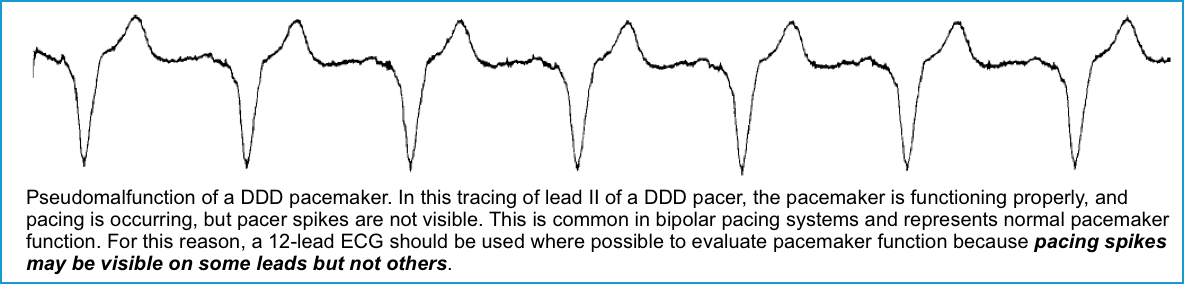

- Pseudo-malfunction

- Pseudomalfunction occurs when pacing is actually occurring, but pacing spikes are not seen or result in “abnormal” rhythms on the ECG despite normal PM function.

- Pseudomalfunction also occurs when the clinician mistakenly expects the pacer to be triggering when it is appropriately inactive.

- The pacemaker is correctly and appropriately inhibited by the presence of regular cardiac activity. The practitioner erroneously interprets the absence of pacer spikes as a malfunction or failure to pace.

Failure to capture

◾️It occurs when a pacing spike fails to trigger a beat.

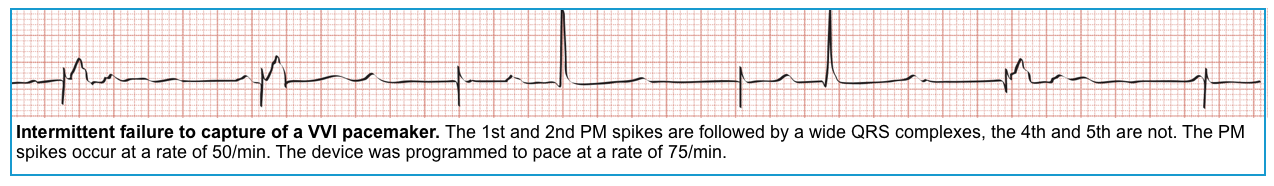

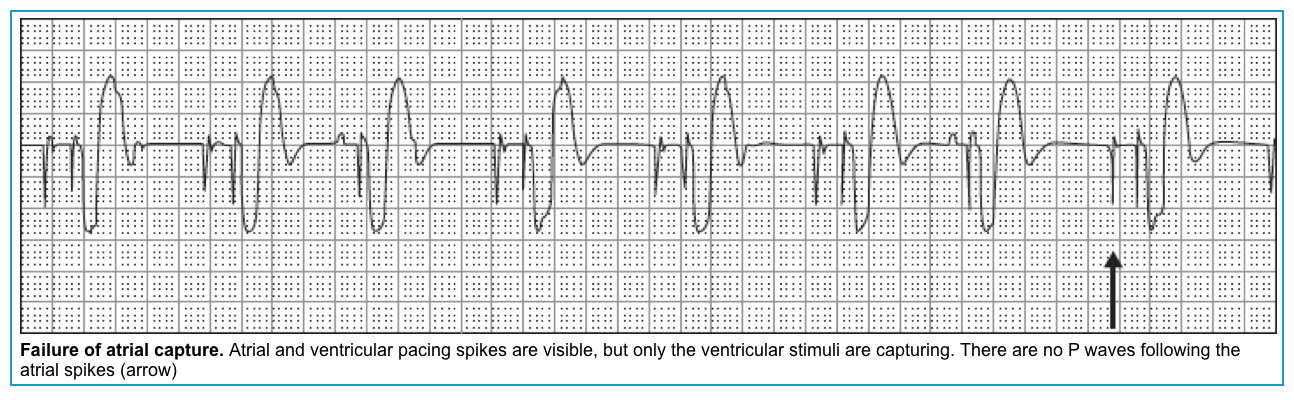

◾️ECG

- Presence of pacing spikes without evidence of capture and depolarization *.

- In atrial pacemakers, this will appear as an atrial pacer spike that does not result in a P wave.

- In ventricular pacemakers, this will appear as a ventricular pacer spike that fails to produce a QRS complex.

- Media 🎥

◾️Causes *

- Low current output

- Allows for enough current to result in a pacer spike on the ECG but not enough to cause myocardial depolarization. This can be caused by:

-

Lead fracture, dislodgement, or an insulation problem.

- If Cardiac perforation by pacer leads happens, a CXR shows the lead tip out of the heart, and an ECG with a paced complex with a new RBBB is suggestive of cardiac lead perforation.

- Battery end-of-life or depletion.

-

- Allows for enough current to result in a pacer spike on the ECG but not enough to cause myocardial depolarization. This can be caused by:

- Elevation in the myocardial voltage threshold

- The myocardium requires a higher voltage to result in depolarization. This can happen in the following conditions:

- Myocardial ischemia/infarction *

- Metabolic derangements

- Electrolyte disturbances (especially hyperkalemia)

- Hypothyroidism

- Hypoxemia

- Acidemia

- Medications (esp. antidysrhythmics, e.g., amiodarone), usually at supratherapeutic levels, can elevate the pacing threshold.

- External defibrillation can cause inability to capture in >50% of patients with pacemakers *.

- The myocardium requires a higher voltage to result in depolarization. This can happen in the following conditions:

| ⚪️Severe hyperkalemia may cause ECG changes to be mistaken for pacemaker malfunction. ⚪️The pacing threshold is elevated in hyperkalemia, leading to increased latency, loss of capture, as well as loss of sensing *. ⚪️Definitive treatment for hyperkalemia should be instituted without delay. |

Pacemaker-Mediated Dysrhythmias

◾️Pacemakers can be useful to treat or prevent dysrhythmias, but can themselves become a source of dysrhythmias. These may include the following:

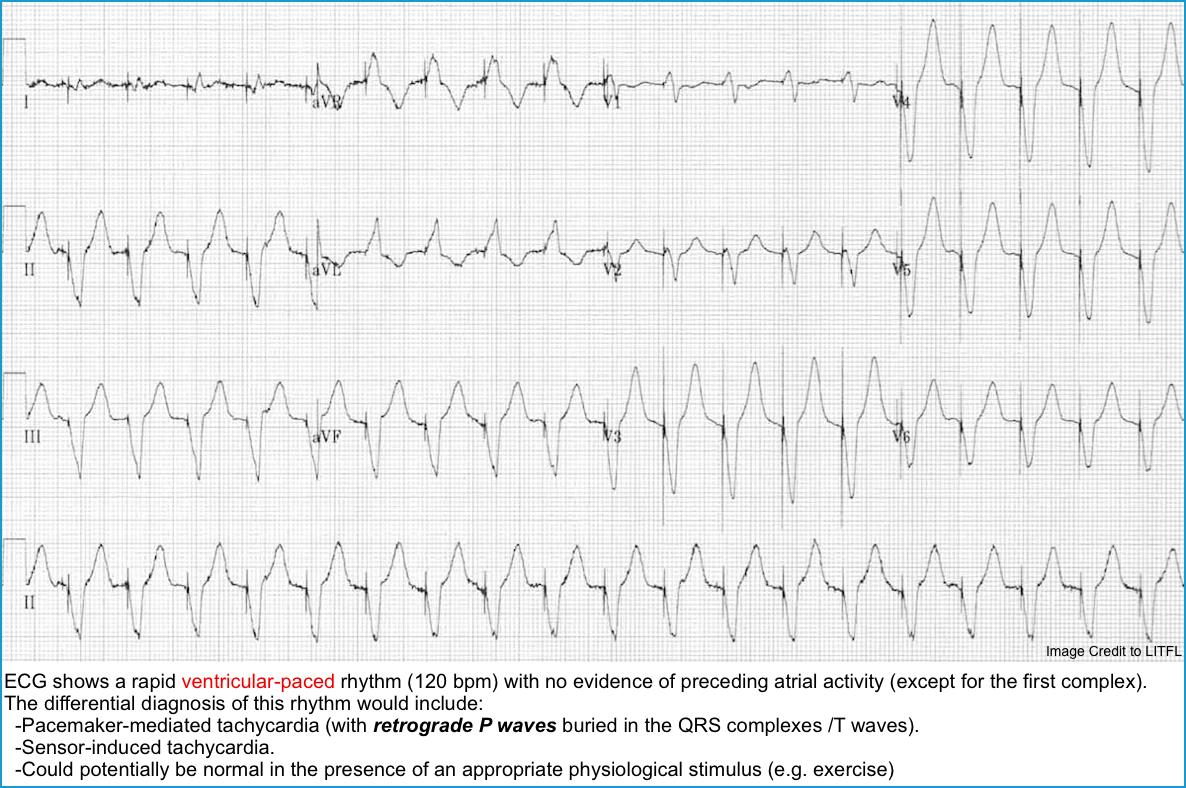

- Pacemaker-Mediated Tachycardia (PMT), aka endless-loop tachycardia.

- More common in DDD pacemakers *.

- Mechanism

- Endless loop tachycardia due to a reentrant circuit (the most common mechanism) *

- Tracking of sinus tachycardia or atrial arrhythmias.

- Tracking of electromagnetic devices.

- ECG: A rapid, regular ventricular-paced rhythm, at a rate at or less than the maximum upper rate of the pacemaker (usually 160 to 180 bpm) *. See figure below.

- Rarely, the inciting event (PVC with retrograde P wave, oversensing, magnet removal) may be captured on a rhythm strip.

- Differential diagnosis

- Sensor-induced tachycardia.

- Atrial tachycardia (there is a true atrial tachycardia, such as sinus tachycardia, or AF, and the pacemaker communicates this to the ventricles).

- Management: Application of the magnet 🧲 to initiate asynchronous pacing and break the reentry circuit.

- Dysrhythmias due to lead dislodgement

- Definition: A dislodged lead can cause malfunctions in the pacing system, such as loss of capture, inadequate sensing, or impedance abnormalities *.